- 201 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

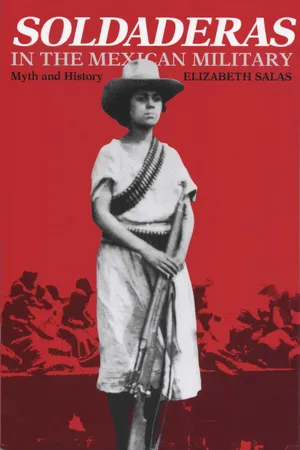

This study explores the evolving role of women soldiers in Mexico—as both fighters and cultural symbols—from the pre-Columbian era to the present.

Since pre-Columbian times, soldiering has been a traditional life experience for innumerable women in Mexico. Yet the many names given these women warriors—heroines, camp followers, Amazons, coronelas, soldadas, soldaderas, and Adelitas—indicate their ambivalent position within Mexican society. In this original study, Elizabeth Salas challenges many traditional stereotypes, shedding new light on the significance of these women.

Drawing on military archival data, anthropological studies, and oral history interviews, Salas first explores the real roles played by Mexican women in armed conflicts. She finds that most of the functions performed by women easily equate to those performed by revolutionaries and male soldiers in the quartermaster corps and regular ranks. She then turns her attention to the soldadera as a continuing symbol, examining the image of the soldadera in literature, corridos, art, music, and film.

Salas finds that the fundamental realities of war link all Mexican women, regardless of time period, social class, or nom de guerre.

Since pre-Columbian times, soldiering has been a traditional life experience for innumerable women in Mexico. Yet the many names given these women warriors—heroines, camp followers, Amazons, coronelas, soldadas, soldaderas, and Adelitas—indicate their ambivalent position within Mexican society. In this original study, Elizabeth Salas challenges many traditional stereotypes, shedding new light on the significance of these women.

Drawing on military archival data, anthropological studies, and oral history interviews, Salas first explores the real roles played by Mexican women in armed conflicts. She finds that most of the functions performed by women easily equate to those performed by revolutionaries and male soldiers in the quartermaster corps and regular ranks. She then turns her attention to the soldadera as a continuing symbol, examining the image of the soldadera in literature, corridos, art, music, and film.

Salas finds that the fundamental realities of war link all Mexican women, regardless of time period, social class, or nom de guerre.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Soldaderas in the Mexican Military by Elizabeth Salas in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9780292787667Subtopic

Mexican History1 Mesoamerican Origins

In myth Snake Woman was the war god’s mother. She was there to trigger those wars over which her son, as the god of war, presided. He was the doer and the victory bringer, she the inciter.

—Burr Cartwright Brundage

In many Mesoamerican societies, women figured prominently as both war goddesses and legendary warriors. The connection between these myths and real women who engaged in warfare is often obscured by scholars. As Brundage shows, the study of war goddesses focuses on their symbolic roles as bloodthirsty demons and provocateurs of male warriors. Miguel León-Portilla, embellishing the same theme, surmises that the Mexicas believed that Ometeotl, the cosmic being, was both “father and mother” and in “his maternal role he was Coatlícue [the Great Mother] and Cihuacóatl [Snake Woman].”1

While war gods like Mixcóatl and Huitzilopochtli are thought to have been real male warrior leaders later deified into myth, the same conclusions are not drawn about the war goddesses, Cihuacóatl and Coyolxauhqui. Rather, war goddesses and female warrior leaders are viewed as mythical fantasies created by men and not at all reflective of women’s varied roles over several centuries as tribal leaders, defenders, and warriors.

Motherhood was unquestionably the most important role for women in Mesoamerica. In mythical accounts, it was deified into a series of Earth Mothers who had tremendous powers for good and evil. Often in myth the Earth Mother’s most common manifestation was as a war goddess. The fusion of the Earth Mother/war goddess in myth equates to a fundamental aspect of tribal life. Mesoamerican women lived in tribes that gradually migrated into the Valley of Mexico. Along the trek, both men and women helped lead and defend their tribe from enemies. This tribal tradition is reflected in religious myths about the Earth Mother who at certain times becomes a war goddess or tribal defender. This mother/war goddess combination appears in legends about Toci (Our Grandmother) and her warrior manifestation, Yaocihuatl (Enemy Woman), and was reinforced in later generations in various combinations such as Itzpapalótl/Itzpapalótl (Obsidian Knife Butterfly [both manifestations are warlike]), Serpent Skirt/Chimalman (Shield Hand), Coatlícue (Lady of the Snaky Skirt)/Coyolxauhqui (She Is Decorated with Tinkling Bells, Golden Bells), Coatlícue/Cihuacóatl (Snake Woman), and in later times Our Lady of Guadalupe/María Insurgente (Insurgent Mary).2

The Earth Mother/war goddess fusion emerged from the political, economic, and social structure of many early Mesoamerican tribes wherein some powers related to inheritance, property, and tribal defense passed from mother to daughter. Don Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl, a Mexica himself, remarks that at Tula (an ancient center of civilization), “women had held supreme power.”3 Eric Wolf notes the possibility that in some early cultures “descent through females provided the main organizing principle of social life.”4 Women, as the strategic sex in reproduction and production and gathering of food, could hold power because “property in houses, goods and crops” often passed through female lines.5 Women’s powers extended, often out of necessity, to include that of warrior or tribal defender.

Artifacts of Toci (the most ancient Earth Mother deity from the Valley of Mexico), known as “Our Grandmother” by later tribes, depict her armed with a shield in one hand and a broom in the other, perhaps symbolizing the dominance of woman as domestic chief (mother) and war chief (daughter). The most common form for Toci was as a goddess of war named Yaocihuatl. The name Yaocihuatl, which means Enemy Woman, probably was used by later generations of male warrior nations to discredit female warriors. It is quite possible that Yaocihuatl was in real life or in myth the “daughter Amazon” or war chief of the tribe.6

Itzpapalótl and her warlike manifestation, of the same name, come from the ancient Chichimeca tribes that migrated from the far north to the Valley of Mexico. Described as having a fleshless face and talons instead of hands and feet, she was closely identified with war and hunting. She is referred to as an “authentic Chichimeca deity” in that “she was never tamed.”7 This description suggests that Chichimeca women were acknowledged fighters who defied defeat.

In many instances it was necessary for women to fight in defense of their families, kinship groups, and property. Tribes that migrated into the Valley of Mexico after A.D. 800 often faced constant intertribal warfare. Both men and women had to aid in the common defense of the tribe, with women fighting in three ways: as individuals, together with men, or in separate women’s groups led by women. Over time, defense of tribes evolved into protection of towns and the nation.

There is some archeological evidence of female tribal defenders. Totonac figurines found in the vicinity of Veracruz (ca. A.D. 600–800) depict women as “veritable Amazons, bare waisted, serious faced, carrying shields and wearing huge headdresses.”8 More substantive evidence of female tribal defenders comes from legends of the Toltecs, the cultural progenitors of the Mexicas. Women fought side by side with men for Topiltzin until the tribe was destroyed in A.D. 1008.9

The Selden Codex (ca. A.D. 1035) tells the legend of the Warrior Princess. The story line accompanying the pictographs states:

According to legend, men were born from trees. But Princess Six Monkey has parents of flesh and blood. Upon defending his kingdom, her father, Ten Eagle–Stone Tiger, takes the nobleman Three Lizard prisoner, but loses his three sons. Upon advice from the priest Six Buzzard the princess decides to defend her right to the throne . . . she becomes the wife of Prince Eleven Wind. . . . The priest Two Flower takes the princess to her husband’s town. On the way, enemies of the princess insult her . . . the priestess Nine Grass advises her to punish the rebels. The ones who insulted her are taken prisoner by Six Monkey. Sweet revenge. Sacrifice of the chieftain. Six Monkey and Eleven Wind live happily ever after.10

The story shows that a priestess told Six Monkey that she should use force to defend her honor and the right to her father’s kingdom. A woman who defended her people by creating and leading a women’s battalion is Toltec Queen Xochitl (ca. A.D. 1116). The wife of Tecpancaltzin, Xochitl called women for military service and led them into a battle that cost her life.11

While some ancient myths depict female warriors holding their own with male warriors, other myths stress the dominance of the male warrior. Such is the case with the changing story about the origin of the Mexicas. Early in their wanderings, women played a significant role. The Mexicas in fact named themselves after Mecitli (Maguey Grandmother), a symbol of immense fecundity. In an early version of the myth of origins it is said that the Mexicas began “their wandering with two deities—Mecitli and a male form of Mixcóatl.”12

As the Mexicas progressed farther into the Valley of Mexico, the myth of their origins was updated. The Earth Mother became Serpent Skirt and her warlike manifestation, or daughter, bore the name of Chimalman. This story focused on the confrontation between Chimalman and a more mature Mixcóatl (ca. A.D. 900). Mixcóatl set out to conquer new lands (in the state of Morelos) and found himself facing the region’s warrior goddess Chimalman. Even though he was a powerful warrior, Mixcóatl’s four arrows (the symbol for taking possession of new lands) did not kill Chimalman, as she was able to deflect them from her body. She then “shot her arrows and darts” at him without success. Chimalman returned to her caves but had to surrender after “Mixcóatl had raped her nymphs (servants).”13

Some time after entering the Valley of Mexico, perhaps in A.D. 1143, the Mexicas dethroned a prominent female warrior leader named Coyolxauhqui. While little is known about the real Coyolxauhqui, in myth she is said to be the Amazon daughter of the Earth Mother Coatlícue, her avatar and a titan. The male warrior who fought Coyolxauhqui and her many brothers for power and control of the Mexicas was the youngest brother, Huitzilopochtli. Allied with him was the Earth Mother Coatlícue.

The conflict suggests a shift away from the mother/daughter mythical relationship to a mother/son relationship. The suggested cause of the conflict may have been a rift between Coatlícue, the matriarch, and Coyolxauhqui, her Amazon daughter. Coyolxauhqui may have rebelled against Coatlícue to establish a more systematic and rational way to govern the tribes. According to Adela Formoso de Obregón Santacilia, Coyolxauhqui “ordered the end to warfare and warrior groups” and called for the “establishment of cities not based on warfare.”14

Another view of the mythical conflict involves sibling rivalry among the children of Coatlícue. Huitzilopochtli, the youngest brother, was the personification of a “sexual revolution” in which men came into dominance as warriors and war chiefs. In order to redefine “civilization” along male lines, Huitzilopochtli seized on the conflict between Coatlícue and Coyolxauhqui to assert himself as a powerful war chief with a new destiny for the Mexicas.15

The Crónica Mexicayotl, written by Fernando Alvarado Tezozomoc (a Mexica) in 1609, cites the reasons for the revolution: “And the reason Huitzilopochtli went off and abandoned his sister, named Malinalxoch [another name for Coyolxauhqui] along the way, . . . was because she was very evil. She was an eater of people’s hearts, an eater of people’s limbs—It was her work—a bewitcher of people.”16 Coyolxauhqui allegedly used magic to hurt the opposition. The redefined “destiny” of the Mexicas under the new war chief Huitzilopochtli, according to Tezozomoc, was to continue warfare: “When I came forth, when I was sent here, I was given arrows and a shield, for battle is my work. And with my belly, with my head [references are to sacrifice of humans], I shall confront the cities everywhere. . . . Here I shall bring together the diverse peoples, and not in vain, for I shall conquer them.”17

While the battle to depose Coyolxauhqui was successful, Huitzilopochtli was not yet powerful enough to challenge the Earth Mother Coatlícue for complete control. Instead, homage to Coatlícue and her war manifestation, Cihuacóatl, the “inciter” of war, was still necessary.

As the Mexicas gained greater control of the Valley of Mexico a more complex, male-dominated religious, military, and bureaucratic state developed. But the change from a past where women could be warriors and war chief to male dominance in these areas was an uneven process. The Earth Mother/war goddess combination that the Mexicas reinterpreted to suit their growing patriarchy shows that change took time and involved the destruction of their reputation. The next step in the severance of the people from the Earth Mother/war goddess cult was to make the latter into monsters. So it was that the Mexicas created the Earth Mother Coatlícue (her statue is a monstrosity) and her warlike manifestation, Cihuacóatl (blood drips from her shark-toothed mouth). In the “Song of Cihuacóatl,” found in the Florentine Codex (1570), male warriors prayed to Cihuacóatl for a good war:

Our Mother

War Woman

Deer of Colhuacán

In plumage arrayed

The sun proclaims the war

Let men be dragged away

It will forever end

Deer of Colhuacán

In plumage arrayed18

Even though the war chief, Huitzilopochtli, called for battle, he still had to ask Coatlícue and Cihuacóatl to rouse warriors.

The Mexicas, according to Brundage, merged the previous war goddesses Yaocihuatl and Coyolxauhqui with Cihuacóatl. In the Florentine Codex, she is even further discredited as the “savage Snake-woman, ill-omened and dreadful, who brought men misery.”19 Cihuacóatl, it was said, “giveth men the hoe and the tumpline. Thus she forceth men to work. And when she appeared before men, she was covered with chalk, like a court lady with obsidian earplugs. She was in white, having garbed herself in white, in pure white. Her tightly wound hairdress rose like two horns above her head. By night she walked weeping and wailing, a dread phantom foreboding war.”20 This description of Cihuacóatl would later be the basis of the very popular Mexi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Mesoamerican Origins

- 2. Servants, Traitors, and Heroines

- 3. Amazons and Wives

- 4. In the Thick of the Fray

- 5. We, the Women

- Photo section

- 6. Adelita Defeats Juana Gallo

- 7. Soldaderas in Aztlán

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index