eBook - ePub

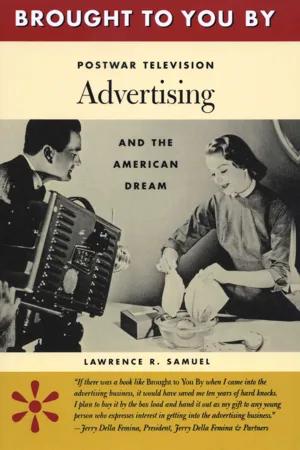

Brought to You By

Postwar Television Advertising and the American Dream

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A lively history" of how TV advertising became a defining force in American culture between 1946 and 1964

(

Technology and Culture).

The two decades following World War II brought television into homes and, of course, television commercials. Those commercials, in turn, created an image of the postwar American Dream that lingers to this day.

This book recounts how advertising became a part of everyday lives and national culture during this midcentury period, not only reflecting consumers' desires but shaping them, and broadcasting a vivid portrait of comfort, abundance, ease, and happy family life and, of course, keeping up with the Joneses. As the author asserts, it's nearly impossible to understand our culture without contemplating these visual celebrations of conformity and consumption, and this insightful, entertaining volume of social history helps us do just that.

The two decades following World War II brought television into homes and, of course, television commercials. Those commercials, in turn, created an image of the postwar American Dream that lingers to this day.

This book recounts how advertising became a part of everyday lives and national culture during this midcentury period, not only reflecting consumers' desires but shaping them, and broadcasting a vivid portrait of comfort, abundance, ease, and happy family life and, of course, keeping up with the Joneses. As the author asserts, it's nearly impossible to understand our culture without contemplating these visual celebrations of conformity and consumption, and this insightful, entertaining volume of social history helps us do just that.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Brought to You By by Lawrence R. Samuel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Advertising. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Home Sweet Home

Chapter One

The Precocious Prodigy, 1946–1952

Why don’t you pick me up and smoke me sometime?

Muriel the talking cigar, 1951

This is the story of the birth of the most powerful advertising medium in history, a story that has never been fully told. In the seven or so years following the end of World War II, the fledgling upstart medium of television advertising would irrevocably alter the social, economic, and political landscape of the United States. Over the course of the latter 1940s and early 1950s, television advertising emerged as a lightning rod of passion and conflict, electrifying politics, the legal system, and of course, everyday life in America. Like the beginnings of most new technologies, the first era of commercial television was a wild and wooly period fueled by an entrepreneurial spirit, gold rush mentality, and corporate interests. Its frontier orientation recast the trajectory of advertising, broadcasting, and marketing, and the careers of those working in those fields. Within this relatively short period of time, a new, original culture would form and be canonized in literature, film, and television itself. Most important, television advertising emerged as a loud, and I believe the loudest, voice of the American Dream, promoting the values of consumption and leisure grounded in a domestic, family-oriented lifestyle. After the Depression and the war, television advertising took on the important responsibility of assuring Americans that it was acceptable, even beneficial to be consumers. A vigorous consumer culture, largely suspended for the previous decade and a half, was about to be primed by the biggest thing to hit advertising since the commercialization of radio in the 1920s.

As in the case of many key sites of twentieth-century American social history, the creation of television advertising was dependent upon a series of technological advances and regulatory decisions. Commercial television began in earnest in the mid-1930s when RCA, Philco, Allen B. Du Mont, and others started testing the medium. NBC and CBS began broadcasting in 1939, with RCA offering sets for $200–$600. Television made its grand debut at the 1939 World’s Fair, and by May 1940, twenty-three stations had begun telecasting in the United States. As America shifted to a wartime economy, however, the FCC soon put limits on commercial operations, which slowed growth of the new medium and made new sets impossible to find in the marketplace. No sets were allowed to be manufactured or stations to be licensed during World War II, postponing commercial television despite technological readiness.1

Months before America’s entry into the war, however, a handful of brave advertisers gained their first experience with the medium. The first television commercial was for Bulova watches, aired during a July 1, 1941, broadcast of a Brooklyn Dodgers versus Philadelphia Phillies baseball game. The history-making event was inauspicious at best, made possible when the FCC authorized WNBT, the New York City NBC affiliate later called WNBC, to allow its broadcasts to be sponsored by advertisers. At precisely 2:29:50 P.M., a Bulova clock showing the time replaced a test pattern, while an announcer told baseball fans it was three o’clock. Bulova paid a total of $9 for the twenty-second spot—$4 for the time and $5 for “facilities and handling.” Later that same day, Sunoco Oil, Lever Brothers, and Procter and Gamble sponsored broadcasts on the station, each paying $100 to reach what was estimated as 4,500 viewers. WNBT’s rate card (the price list given to advertising agencies and sponsors) was, from today’s standards, ridiculously basic, offering media buyers the simple choice of “night” or “day” rates.2

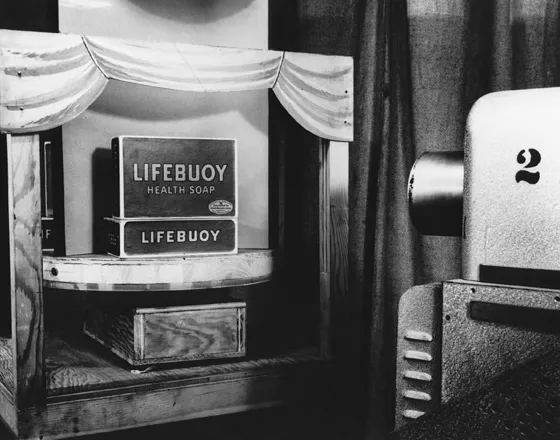

Despite the wartime moratorium on new stations, some existing ones were permitted to test the waters of commercial television. In March 1943, for example, WABD, the New York television station owned by Du Mont Laboratories, offered free time to advertising agencies to experiment with the medium. Ruthrauff & Ryan was the first agency to take Du Mont up on its offer, producing a weekly half-hour show called Wednesdays at Nine Is Lever Brothers Time. The variety show was a vehicle to promote three Lever brands—Rinso detergent, Spry baking ingredients, and Lifebuoy soap and shaving cream. Lever’s commercials were surprisingly sophisticated, using dissolves, superimposed images, and even identical twins to create special effects. Most impressive, however, were commercials that were integrated within the program itself. In one skit, for example, the master of ceremonies led a game of charades, with the correct answer one of the sponsor’s slogans, “A daily bath with Lifebuoy stops B.O.” In another show, a lost puppet character is found in a giant Rinso box, and told he will win over a girl puppet by offering her “a life free of household drudgery” by using Rinso. These early commercials laid the groundwork for advertisers’ use of television to sell products under the guise of entertainment, a strategy advertisers had used since the early days of radio and before in newspapers and magazines.3

A 1944 commercial for Chesterfield cigarettes on the Du Mont network not surprisingly depicted a military scene. (NMAH Archives Center, Smithsonian Institution)

Radio Days

Indeed, much of the unapologetic commercialism of early television was predicated on the structural familiarity of radio. Karen S. Buzzard has noted that radio shows were “conceived, more or less, as one continuous commercial,” best evidenced by the fact that the shows often carried the sponsor’s name, for example, “Lux Radio Theater.” In her book Selling Radio, Susan Smulyan wrote that sponsors’ ultimate goal in radio was to create a “program [which] personifies the product.” Clicquot Club was perhaps the best example of this pursuit, as the beverage marketer and its agency designed their radio program around the physical attributes of the product, specifically peppiness and effervescence. With snappy music and lively chatter, Clicquot Club’s radio program was an audible metaphor for the bubbly tonic. J. Walter Thompson was recognized as the master of the radio program as advertisement, its goal to, in one advertising executive’s words, “get radio shows that would work as advertising.”4

In his definitive book on advertising in the 1920s and 1930s, Advertising the American Dream, Roland Marchand too has noted radio’s “dovetailing of entertainment with advertisement.” Radio commercials often resembled the tone, locale, and pace of their host programs or, better yet, used the programs themselves as the advertising delivery vehicle. A barber on the Chesebrough “Real Folks” radio show was known to casually praise the value of Vaseline while shaving a customer, while characters on the Maxwell House Program chatted up the merits of the coffee. This interweaving of entertainment and advertising, Marchand points out, was in fact not original to broadcasting but had its origins in print. Advertising agencies had long practiced the art of “editorial copy,” in which newspaper and magazine ads were blended into articles through similar type fonts and writing style. With their presentation of entertainment-as-advertising (or advertisement-as-entertainment), television advertisers were carrying on an established industry tradition known to be an effective technique to sell products and services. Advertisers and their agencies exploited this successful formula in television by producing most of the programs and simply buying blocks of airtime from the networks. This system would serve the advertising community well during this first decade of commercial television, until a series of events irrevocably altered the industry’s underpinnings.5

Another 1944 commercial on Du Mont for Rinso White detergent featured this scene right out of a Norman Rockwell painting. (NMAH Archives Center, Smithsonian Institution)

State-of the-art production techniques in the 1940s by the Du Mont network included this lazy Susan turntable which was swiveled around to reveal an oversized box of Lifebuoy soap and other products. (NMAH Archives Center, Smithsonian Institution)

The Race Is On

With the invention of the Image Orthicon tube during the war, making possible a cheaper yet better product, television was now ready to be much more than what Miller and Nowak called a “clumsy and expensive toy.” Television began to earn true legitimacy in 1945 when an allied victory in World War II seemed assured, part of the “guns-to-butter” transition from a military-based economy to a consumer-based one. As factories retooled in the months following the end of the war, advertising agencies and their sponsors moved quickly. Immediately after the FCC announced in June 1945 that prewar spectrum standards would be resumed, in fact, many advertising agencies rushed to create television departments, just as they had quickly created radio departments a generation earlier when they saw opportunity. Marchand has observed that once advertisers fully realized the power of radio shows to function as extended commercials, radio departments within ad agencies grew significantly in both number and importance. In mid-1945, about thirty ad agencies already had television departments, although “department” perhaps overstates the resources agencies were allocating to the new medium. Many of these departments consisted of a single person or were small groups within existing radio departments (not unlike the interactive or “new media” departments of agencies circa mid-1990s). Some departments were assigned the exclusive task of monitoring industry events, while others were given the charge to jump into the cutting edge technology. In addition to Ruthrauff & Ryan, the first agencies to make a commitment to television included Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborne (BBDO), J. Walter Thompson, Young & Rubicam, N. W. Ayer, Compton Advertising, and Kenyon & Eckhardt.6

Given the extremely limited size and scope of television immediately after the war, the advertising business was already taking the medium fairly seriously. According to the Television Broadcasters Association, in the summer of 1945 the country’s nine television transmitters were reaching a total of fewer than 10,000 sets, all of course in large cities. Of these 5,000–6,000 sets were located in the New York City-New Jersey-Philadelphia area, 800 to 1,000 in the Chicago area, and 500–700 in or around Los Angeles. Set ownership in the early years of television was generally limited to the wealthy, what one publication termed “the mink coat and luxury car class.” Most agencies active in television were producing their own shows (commercials as we know them were still about a year away), although a handful of independent production companies had already sprung up. Despite the rumblings in the advertising world and interest among the more curious to own a television set, few people in 1945 recognized the potential commercial applications of the medium. Some believed that television would be most effective as an internal selling device within department stores. In October and November 1945, Gimbel’s in Philadelphia tested the effectiveness of “intrastore” (what would be later called closed-circuit) advertising, telecasting sales pitches shot live from the central auditorium to twenty receivers scattered around the store. The telecasts did prove to boost sales, although the cost of such a project on a large-scale basis would have been prohibitive.7

On the basis of Gimbel’s test and other localized efforts, it soon became apparent that advertising on a mass scale represented the greatest chances of making television a viable medium. In 1945, $3 billion in advertising was spent in the United States, and the neophyte television industry firmly believed it could grab a share of these dollars. At its annual convention, held in Washington, D.C. on January 29, 1946, the Television Institute trade group focused on the looming opportunity of advertising, addressing questions such as, how much would the process cost the industry? How fast would the audience develop? What technical improvements were necessary? What role would the FCC play? The group boldly assumed that even with production and media costs three to ten times those of radio, television could effectively compete for advertisers’ money. The Institute’s research had indicated that television could “pull” (generate sales) ten times that of radio, a function of the former’s ability to offer both sight and sound. “Action plus animation,” the Institute argued, “create a stepped-up emotional drive lacking in all other forms of advertising art.” Television programming, and its advertising stepchild, were envisioned as drawing from a variety of arts, a powerful fusion of movies, radio, music, writing, and theater. Experts, however, advised sponsors-to-be to purchase a television set so “you can really see whether your program is laying eggs.”8

By the spring of 1946, industry experts were predicting that television advertising would take the form of commercials, or what was described by Sales Management as “one-minute movie shorts.” “Video sales messages,” the trade publication forecast, “are going to be something new in advertising and selling, because television commercials are pretty certain to be 16 mm. film episodes, one minute in length, or less.” Believing commercials would be much like movie trailers (or perhaps bad lovers), the magazine accurately predicted that they would be “something that moves fast, with abundant noise, holds your attention for two or three minutes …, and leaves you [with a] promis[e].” Suggestions regarding the kind of commercials current print and radio advertisers should make were even made. For Campbell Soup, advice was offered that “stress [be] laid on quickness of preparation”; for Arrow shirts, that “comic misfits” and “hints to the bachelor” be employed; and for Mennen, the casting of “a girl say[ing] ‘I like smooth men.’”9

Despite a few naysayers, such as E. F. McDonald, president of the Zenith Radio Corporation, who stated in February 1947 that “advertising will never support large-scale television,” most agency, corporate, and broadcast executives believed that the television advertising train had by then already left the station. Agencies were holding symposiums to learn more about the medium, continuing to build television departments, and urging clients to experiment with commercials while it was inexpensive. With a vested interest in a full revival of a consumer-driven economy, companies such as U.S. Rubber, General Mills, Chevrolet, Ford, Standard Brands, and Standard Oil had all invested in television advertising by the beginning of 1947. These were, not coincidentally, some of the flagship accounts of ad agencies blazing the televisual trail. Helping the industry’s confidence were the long lines of shoppers at Macy’s, pushing and shoving to purchase one of the limited number of ten-inch screen television sets selling for $350. Long lines also formed at retail stores in Chicago, with thousands of customers put on waiting lists to purchase a set when more came in. The frenzy over television was even more remarkable given the fact that most Americans wanting to own a television set had actually never seen one in use. A study completed in summer 1946 by Sylvania Electric Products found that less than one in six consumers who were in the market for a set had ever watched a television show. “Television is going to move very soon and very fast,” Printer’s Ink accurately forecasted in March 1947. Even before most Americans had personally experienced the medium, television was being considered an integral part of postwar domestic life.10

General Foods, an avid radio advertiser, was particularly eager to get in on the ground floor of commercial television. The company set up an advertising committee in 1946 to provide reports of industry goings-on and recommend what steps to take. By May 1947, Howard M. Chapin, sales and advertising manager of the company’s Jell-O division...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part 1: Home Sweet Home

- Part 2: Keeping up with the Joneses

- Part 3: The New Society

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index