- 398 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986

About this book

"A benchmark publication . . . A meticulously documented work that provides an alternative interpretation and revisionist view of Mexican-Anglo relations." –

IMR (

International Migration Review)

Winner, Frederick Jackson Turner Award, Organization of American Historians

American Historical Association, Pacific Branch Book Award

Texas Institute of Letters Friends of The Dallas Public Library Award

Texas Historical Commission T. R. Fehrenbach Award, Best Ethnic, Minority, and Women's History Publication

Here is a different kind of history, an interpretive history that outlines the connections between the past and the present while maintaining a focus on Mexican-Anglo relations.

This book reconstructs a history of Mexican-Anglo relations in Texas "since the Alamo," while asking this history some sociology questions about ethnicity, social change, and society itself. In one sense, it can be described as a southwestern history about nation building, economic development, and ethnic relations. In a more comparative manner, the history points to the familiar experience of conflict and accommodation between distinct societies and peoples throughout the world. Organized to describe the sequence of class orders and the corresponding change in Mexican-Anglo relations, it is divided into four periods, which are referred to as incorporation, reconstruction, segregation, and integration.

"The success of this award-winning book is in its honesty, scholarly objectivity, and daring, in the sense that it debunks the old Texas nationalism that sought to create anti-Mexican attitudes both in Texas and the Greater Southwest." — Colonial Latin American Historical Review

"An outstanding contribution to U.S. Southwest studies, Chicano history, and race relations . . . A seminal book." – Hispanic American Historical Review

Winner, Frederick Jackson Turner Award, Organization of American Historians

American Historical Association, Pacific Branch Book Award

Texas Institute of Letters Friends of The Dallas Public Library Award

Texas Historical Commission T. R. Fehrenbach Award, Best Ethnic, Minority, and Women's History Publication

Here is a different kind of history, an interpretive history that outlines the connections between the past and the present while maintaining a focus on Mexican-Anglo relations.

This book reconstructs a history of Mexican-Anglo relations in Texas "since the Alamo," while asking this history some sociology questions about ethnicity, social change, and society itself. In one sense, it can be described as a southwestern history about nation building, economic development, and ethnic relations. In a more comparative manner, the history points to the familiar experience of conflict and accommodation between distinct societies and peoples throughout the world. Organized to describe the sequence of class orders and the corresponding change in Mexican-Anglo relations, it is divided into four periods, which are referred to as incorporation, reconstruction, segregation, and integration.

"The success of this award-winning book is in its honesty, scholarly objectivity, and daring, in the sense that it debunks the old Texas nationalism that sought to create anti-Mexican attitudes both in Texas and the Greater Southwest." — Colonial Latin American Historical Review

"An outstanding contribution to U.S. Southwest studies, Chicano history, and race relations . . . A seminal book." – Hispanic American Historical Review

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986 by David Montejano in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Mexican History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Introduction

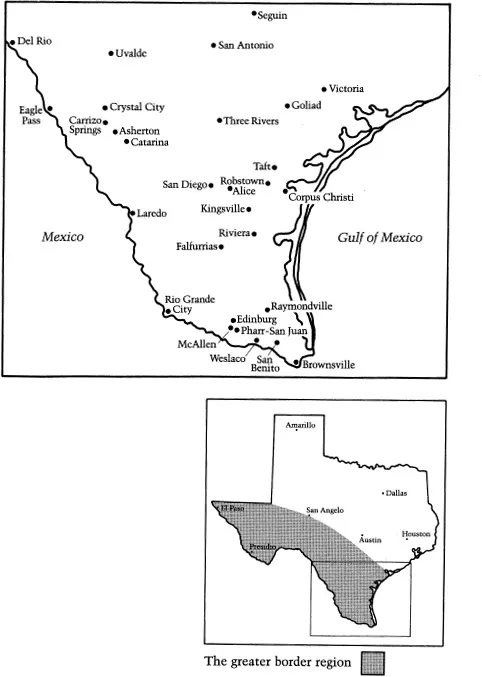

TWO MAJOR concerns guided this work. One was to reconstruct a history of Mexican-Anglo relations in Texas “since the Alamo.” In geographic terms, the focus was primarily directed to a 200-mile-wide strip paralleling the Mexican border from Brownsville to El Paso.1 I considered this history important because of the fragile historical sense most people have of the American Southwest. The vestiges of a Mexican past are still evident. In the old cities of the region, the missions and governors’ palaces, the “old Mexicos,” the annual fiestas, and the like remind one that there is a history here, but it seems remote and irrelevant. There is no memory, for example, of annexation as a major historical event. What happened to the annexed Mexicans? The question points to a larger lapse in memory—what does the nineteenth-century frontier period have to do with the present?

There is, of course, a popular and romanticized awareness of southwestern history—Indians and Mexicans were subdued, ranches fenced, railroads built, and so on until the West was completely won. A “triumphalist literature” has enshrined the experience of the “Old West” in tales of victory and progress.2 Drama, the easiest virtue to fashion for southwestern history, has long taken the place of explanation and interpretation. Because this history has seldom been thought of in economic and sociological terms, much of the road connecting the past with the present remains obscured. When the legendary aspects are stripped away from the frontier experience, for instance, cowboys surface as wage workers on the new American ranches and as indebted servants on the old haciendas; the barbed-wire fence movement of the 1880s becomes not just a sign of progress but an enclosure movement that displaced landless cattlemen and maverick cowboys; and the famed cattle trails commemorated in western folklore become an instrument by which the region was firmly tied into national and international markets. The failure of memory, then, is as much sociological as it is historical.

The absence of a sociological memory is nowhere more evident than in the study of race and ethnic relations in the Southwest. Compared with the significant literature on race relations in the American South, similar work in western Americana appears tentative and uncertain. An extensive literature has addressed the major events—the origins of the Mexican War, the founding of the cattle trails, and so on—but only rarely has the discussion focused on the consequences of these events for the various peoples living in the region. In recent years, a few notable works have begun to investigate this area, but this territory remains largely uncharted.3 It was imperative, in this context, to present a different kind of history, an interpretive history that would outline the connections between the past and the present while maintaining a focus on Mexican-Anglo relations.

South Texas.

My second major concern, then, was to ask this history some sociological questions about ethnicity, social change, and society itself. In one sense, this book can be described as a southwestern history about nation building, economic development, and ethnic relations. In a more comparative manner, the history points to the familiar experience of conflict and accommodation between distinct societies and peoples throughout the world. In describing the situation of Texas Mexicans in the early twentieth century, for example, historian T. R. Fehrenbach has drawn parallels to Israel’s West Bank, French Algeria, and South Africa.4 In contrast to these parallels, the Texas history of Mexicans and Anglos points to a relationship that, although frequently violent and tense, has led to a situation that today may be characterized as a form of integration.

An interpretation that attempts to serve both sociology and history must invariably make some difficult decisions about the organization of the presentation. For the sake of the reader whose interest is primarily historical, I have placed the customary introductory discussion of sociological concepts and methods in an appendix. Those interested in theory and methods should refer to this appendix. Some brief comments about “race” and “development,” nonetheless, are in order here.

A Sociological Overview

A critical limitation in the sociological literature consists of its inability to deal with the race question. Whether the process of social change has been called modernization or capitalist development, the subject of race has been considered a temporary aberration, an irrelevancy in the developmental experience. Industrialization and urbanization were expected to weaken race and ethnic divisions because such distinctions were considered inefficient and counterproductive. As social life underwent a thorough commercialization, common class interests and identities were supposed to completely dominate the politics of the new order, overshadowing parochial and mystical bases of social conflict.

In contrast to these theoretical expectations, the histories of many contemporary societies make evident that economic development and race divisions have been suitably accommodated. But there seems to have been no single pattern or template for a modernizing racial order. Extermination and assimilation have demarcated the most extreme “solutions” to the race question, with several patterns of subjugation and accommodation falling in between. Not surprisingly, given this situation, the literature of race and ethnic relations has yet to progress beyond the construction of various typologies of “outcomes.”5

But patterns can be teased out of the seeming disorder. The study of the Texas border region is ideal in this sense, for its one striking feature has been the presence of great diversity in Mexican-Anglo relations at any one historical point. A symptom of this diversity has been the confusion, among both Mexicans and Anglos, on whether Mexicans constitute an ethnic group or a “race.” This question, as the following history will make evident, has long been a contentious political issue in the region. The clarification of the race concept, in fact, must take into account its political nature, a point that has remained undeveloped in the sociological literature.

One of the better known axioms in the social sciences is that “races” are social definitions or creations. Although race situations generally involve people of color, it is not color that makes a situation a racial one. The biological differences, as Robert Redfield noted some forty years ago, are superficial; what is important are “the races that people see and recognize, or believe to exist,” what Redfield called the “socially supposed races.”6 Generally missed in this type of discussion, however, has been the additional recognition that the race question, as a socially defined sign of privilege and honor, represents an arena of struggle and accommodation. The death or resurrection of race divisions is fundamentally a political question, a question of efforts, in George Fredrickson’s words, “to make race or color a qualification for membership in the civil community.”7 To put it another way, the notion of race does not just consist of ideas and sentiments; it comes into being when these ideas and sentiments are publicly articulated and institutionalized. Stated more concisely, “race situations” exist when so defined by public policy.

Framing the race problem as a political question helps to clear the ambiguity concerning the sociological classification of Mexicans. The bonds of culture, language, and common historical experience make the Mexican people of the Southwest a distinct ethnic population. But Mexicans, following the above definition, were also a “race” whenever they were subjected to policies of discrimination or control.

This political definition of race enables us to sidestep a historical argument about the origins of Anglo-Saxon prejudice—whether these attitudes were imported and transferred to Mexicans or were the product of bitter warfare.8 Both were important sources for anti-Mexican sentiments. Anglos who settled in the Southwest brought with them a long history of dealing with Indians and blacks, while the experience of the Alamo and the Mexican War served to crystallize and reaffirm anti-Mexican prejudice. Nonetheless, this psychological and attitudinal dimension, while interesting, is unable to explain variations and shifts in race situations. The important question is, Under which conditions were these sentiments and beliefs translated into public policy?

In this context, Texas independence and annexation acquire special significance as the events that laid the initial ground for invidious distinction and inequality between Anglos and Mexicans. In the “liberated” and annexed territories, Anglos and Mexicans stood as conquerors and conquered, as victors and vanquished, a distinction as fundamental as any sociological sign of privilege and rank. How could it have been otherwise after a war? For the Americans of Mexican extraction, the road from annexation to “integration,” in the sense of becoming accepted as a legitimate citizenry, would be a long and uneasy one.

Concerning social change and development, ample work in historical sociology has explored the transformation of “precapitalist” agrarian societies into “modern” commercial orders. The importance of this literature for this study lay in the depiction of social change in class terms—in terms of the way landed elites and peasants responded to market impulses and to the emergence of a merchant class. According to the classic European version of this transition, a class of merchants emerged triumphantly over anticommercial obstacles of the landed elite, freeing land and labor of precapitalist restraints and transforming them into marketable commodities. The peasantry was uprooted and converted into a wage laboring class, while merchants and the commercialized segment of the landowning elite become a rural bourgeoisie.9 Generally, however, these European case studies have emphasized internal sources of social change; the merchants were indigenous to the societies they ultimately transformed. The history of the Americas, on the other hand, pointed forcefully to a developmental path of plural societies formed through conquest and colonization.

While the European experience is an inappropriate model for a history characterized by war and “race” divisions, it nonetheless directed attention to familiar actors and to familiar events in the loosening of an elite’s hold on land and labor. Instead of English gentry and merchants, there were the Mexican hacendado and the Anglo merchant-adventurer; instead of yeoman and peasant, the ranchero and indebted peón. And rather than wool, the enclosing of peasant holdings, Captain Swing and the Levellers, we had Longhorn cattle, the enclosing of the open range, and Juan Cortina and Mexican bandits.

In spite of the shortcomings mentioned earlier, then, a relaxed class analysis—one accepting of the political character of race situations—held considerable promise for outlining the structural basis of complex Mexican-Anglo relations. The relevance of the method emerged from the historical figures themselves, from actors who were “class conscious” as well as “race conscious.” Whenever they were given the floor, their speech was punctuated with references to economic status, and their behavior was expressive of class-specific interests. Since these behavior patterns provided a context for Mexican-Anglo relations, understanding the diverse conditions along the border region proceeded through an examination of the divisions and relations between propertied and propertyless, of the way work was organized, of the pace and fluctuations of the market—in short, of the material features of particular societies across space and time.

This line of reasoning led eventually to a view of social change couched in terms of the displacement and formation of distinct class societies. I envisioned such change as a fundamentally uneven process that generally expressed itself through conflict and tension. In a typical sequence, an organic class society—one where social divisions and relations made sense to people—shattered and fell apart under the pressures of market development and the politics of new class groups. There followed a period of uncertainty as a new order was created and began to claim legitimacy from its constituents. The movement was toward the formation of a new class society, one where the ordering of people was again acceptable and appeared natural.

In concrete terms, this meant that the character of Mexican-Anglo relations would reflect the class composition of both the Mexican and Anglo communities and the manner in which this class structure was held together through work arrangements. To state the argument in a highly abbreviated form, Mexican landownership basically settled the question of whether or not Mexicans were defined and treated as racial inferiors. On the other hand, the character of work relations between owner and laborer—whether these were permanent, personalistic bonds or temporary, anonymous contracts—was refracted throughout the social order, shaping the manner in which politics, coercion, incentives, protocol—the stuff of social life—were organized. These work relations, for example, determined whether local politics would be organized through a political machine or through some exclusionary mechanism.

This type of microscopic analysis outlined the basis for explaining the variations in Mexican-Anglo relations in any one period. An underlying implication of this approach was that the arena for development consisted of a patchwork or mosaic of distinct local societies. These local societies were not vague entities but were bounded by administrative and political agencies with the authority to organize and regulate local social life—in the case of Texas, by county and city governments. Thus, whether or not Mexicans were “treated white” reflected the distinct class structure of Texas ranch and farm counties. The sociological patterns became more complex when the urban setting was considered; here the presence of Anglo merchants and an independent Mexican American middle class moderated the segregationist tenor evident in the farm areas. In view of these variations, it makes sense to say that Mexicans were more of a race in one place and less of a race in another.

Social or historical change in Mexican-Anglo relations was likewise made comprehensible through an analysis of the succession of dominant class orders, for these relations varied according to whether the dominant order was characterized by the paternalistic bonds between ranchers and cowboys, the impersonal divisions between growers and farm workers, or the flexible diplomacy between merchants and urban consumers. Briefly stated, the origins, growth, and demise of a racial order in the greater Texas border region corresponded roughly to a succession of ranch, farm, and urban-industrial class societies.

The complexity of race and ethnic relations in the development experience, then, does not signify an absence of order; it means only that the logical key or guide that can unravel the disorder has yet to be discovered. This work attempts to advance this process of discovery.

Organization of the History

If a straight line were teased from an entangled web of directions, Texas border history could be interpreted in terms of a succession of class societies, each with distinct ethnic relations: (a) a Spanish-Mexican hacienda society undermined by the Mexican War in the mid–nineteenth century; (b) an Anglo-Mexican ranch society undermined by an agricultural revolution at the turn of the century; (c) a segregated farm society undermined by world war and an urban-industrial revolution in the mid–twentieth century; and (d) a pluralistic urban-industrial society for the latter half of the twentieth century. This book is organized to describe this sequence of class orders and the corresponding change in Mexican-Anglo relations. Specifically, this history is divided into four periods, which I refer to as incorporation, reconstruction, segregation, and integration.

Part One discusses the experience of annexation and “incorporation.” In the former Mexican territories, pogroms, expulsions, and subjugation of Mexicans were much in evidence where there was a sizable Anglo presence. Generally, however, the au...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Introduction

- Part One. Incorporation, 1836–1900

- Part Two. Reconstruction, 1900–1920

- Part Three. Segregation, 1920–1940

- Part Four. Integration, 1940–1986

- Appendix. On Interpreting Southwestern History

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index