![]()

1

The Lands of Mañana

In 1948 the Los Angeles Times ran a story on Hicks Camp, located just outside the El Monte city boundary. Newly developed bedroom communities in the San Gabriel Valley contrasted sharply with the unpaved and ill-lit neighborhood, and many people were becoming aware of colonias for the first time. “Like a village gathered up in its entirety deep in Old Mexico and brought to the banks of the Rio Hondo here,” the article notes, “barefoot babies squat in the sand and play,” old women tend their flowers in tin cans, and “old men sleep like book ends, folded against a shed wall in the afternoon sun.” The claim that some “shacks” were erected in the nineteenth century, when the land baron Elias Jackson Baldwin (known locally as “Lucky” Baldwin) owned a sizable portion of the San Gabriel Valley, only punctuates the anachronistic image. The tenor of the article is clear: Mexican colonias were not only a withering remnant of a bygone California past, but they were on the brink of removal as Los Angeles sprawled into the periphery.1 This marked the beginning of the end for colonias throughout Southern California. As mass residential and industrial suburban developments encroached on rural spaces, the region entered a new metropolitan phase of its history—one that depended on the erasure of the built environment of its Mexican past.

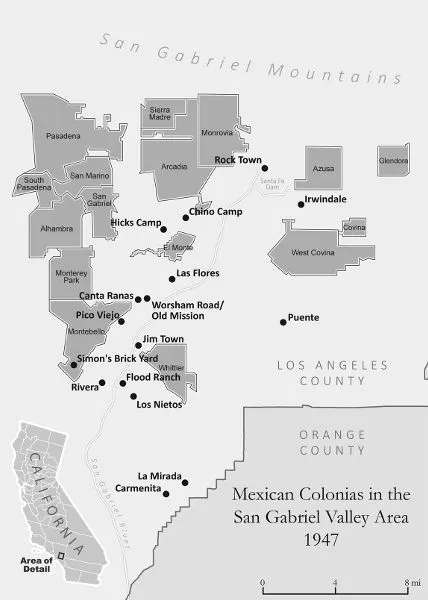

Colonias in metropolitan Los Angeles functioned in significant ways as racially segregated, working-class suburbs.2 By 1940 more than two hundred such communities could be found adjacent to citrus orchards, berry patches, avocado groves, walnut farms, brickyards, railyards, and oil plants up and down California. Locally, they housed economic migrants and refugees from the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920, as well as their American-born children, in every place around the region: Orange County, Riverside County, the Inland Empire, the San Fernando Valley, the San Gabriel Valley, and southeastern Los Angeles County along the Rio Hondo and San Gabriel River.3 Most ethnic Mexicans remained confined to these places because race-restrictive covenants barred access to more affluent neighborhoods. As segregated settlements, colonias were anything but accidental. Growers deliberately organized racialized space in the citrus region of eastern Los Angeles County while simultaneously developing a pattern of employment centered on Mexican labor. Driven by their desire to minimize the impacts of labor unrest, growers replaced Chinese, Japanese, Native American, Sikh, and white farm labor with Mexican labor by the 1920s. To maintain order, growers also participated in efforts to suppress Mexican labor activism, in part by strictly maintaining residential segregation.4 Citrus growers were among a cadre of professionals and industrialists who contributed to a segregated Mexican American world. For example, Simons Brickyard in the Los Angeles suburb of Montebello employed a majority Mexican labor force who lived in the company-owned neighborhood even though the surrounding neighborhoods barred nonwhite homeownership.5 Likewise, the colonia of Flood Ranch on the east bank of the San Gabriel River housed the oil-field workers who propped up Santa Fe Springs’s local economy.

Work and home overlapped in meaningful ways in these spaces. While agricultural and industrial jobsites abounded, the labor invested in the homes and neighborhoods reflected the blue-collar characteristics of colonias just as much as the wage-based employment in which they were engaged. Residents often built and maintained their own homes; designed and repaired local infrastructure; and used their homes as places of profit, protest, and labor organizing. In many ways this do-it-yourself spirit reflected the prewar conditions of rural suburban communities regardless of race. Based on this kind of sweat equity, working-class whites created a community in South Gate. The Great Depression also ensured that rural suburban residents fended for themselves in the absence of state assistance. On the other hand, the crisis caused by the Depression made it possible for working-class whites to move up economically by using the tools of the state. The Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) had a significant impact on shaping the direction of property wealth in ways that explicitly excluded people of color and benefited whites. By 1939 owner building had begun a steady decline in areas under consideration for federal mortgage insurance through the FHA. By contrast, areas where owner building persisted, such as colonias, constituted too great a security risk to receive federal backing. Thus the significant difference between working-class people in these rural suburbs rested on the structural benefits attached to racial whiteness.6 In the absence of significant private investment or government intervention, Mexican workers were forced to maintain their communities as best they could. Within the context of suburban expansion, neglect by civic officials opened up the possibility to eventually usurp land occupied by ethnic Mexicans.

The mass migration of workers into Los Angeles drawn by industries related to World War II exacerbated a regionwide housing shortage and placed a new imperative on securing developable land. Local officials relied on federal programs and private enterprise to alleviate the problems caused by overcrowding and underdevelopment by building up outlying districts. A report published by the California Reconstruction and Reemployment Commission in 1944 noted a massive spike in the state’s population. More than 1.5 million people had made a new home in California since the census taken in 1940, and Los Angeles had gained 301,410 of those transplants, boosting the metropolitan population to more than 3 million inhabitants.7 A building bonanza ensued that replaced vast agricultural lands with tract developments, industrial parks, and freeways. Residents of colonias experienced this metropolitan transformation largely as a threat to the communities that they had worked so hard to build and defend. It was in the postwar era that the once isolated communities of Mexican workers moved from the periphery of the metropolis to the center. Large-scale production of residential tracts and industrial parks gobbled up agricultural territory. With a large number of residents losing wage work with the dying agricultural industry, and with a lack of public investment to improve conditions, these communities languished in a restructured landscape of suburban prosperity. The origins of this struggle lay in the Great Depression. when colonias emerged as sources of concern over blight.

“Typical Semi-Tropical Countryside Slums”

The administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) enabled unprecedented government intervention in the housing market in response to the Great Depression.8 Formed at FDR’s direct behest, the HOLC placed the power of the federal government behind individual homeowners in danger of default. Initially serving as an active lending agency, the HOLC financed over $30 billion in emergency loans for more than a million mortgages between 1933 and 1935. Nationally, 40 percent of eligible homeowners turned to the federal government for assistance in saving their homes from default. Aside from direct lending, the HOLC introduced the self-amortized, low-interest, long-term loan as a mechanism to bring order to the chaotic home loan industry and ensure that homeowners could fully pay off their houses without wild market fluctuations derailing their ability to pay. As a result, it became possible to complete repayment at a standardized monthly mortgage for a period of twenty years. The thoroughness with which the organization appraised metropolitan regions across the nation set a precedent for federal government home loan financing, as the FHA would soon adopt the standardized appraisal methods advanced by the HOLC. The meticulous set of metrics used to assess the conditions of neighborhoods culminated in a hierarchy of letter grade designations. A-grade neighborhoods were the most likely to receive federal assistance and corresponded with a green color code represented on city survey maps. B grades were assigned blue spaces on the maps, C grades received yellow, and D-graded areas donned the notorious red shade on the survey maps. The latter score, commonly known as “red lining,” represented the lowest designation assessed by HOLC appraisers for weathered and ill-repaired buildings, lack of infrastructural improvements, and most notably, having large immigrant and/or racial minority populations. Lack of race-restrictive covenants in property deeds resulted in red grades almost every time.9 Colonias closest to the city received appraisals based on their proximity and because they were likely to be incorporated into the expanding metropolis eventually.

Similarly, as residential spaces that attracted working-class migrants from Mexico as well as refugees from the American Plains region, colonias and other rural settlements became sites of great concern for public officials. In 1930 there were more than 175,000 Mexicans in Los Angeles County, with more than 72,000 living outside the city limits.10 The growth of the population slowed and eventually declined in the 1930s because of the intertwined factors of repatriation, a national program designed to return undocumented Mexican residents to their country of origin (although for many it was the first time they would set foot on Mexican soil), and the effects of the Great Depression, which stymied immigration.11 By 1940 the ethnic Mexican population in Los Angeles stood at 61,248, most of whom had been born in the United States.12 These folks adapted by blending Mexican and American cultural practices amid stifling poverty and inequitable labor conditions.13 By contrast, the economic crisis of the 1930s provided an impetus to migrate to California from the hardest hit areas of the country. Pejoratively called “Okies,” migrants from Oklahoma sought work in Southern California and settled in agricultural and industrial areas adjacent to colonias. Dust Bowl migrants poured into metropolitan Los Angeles in heavy numbers during the Great Depression. Between 1935 and 1940 alone an estimated ninety-six thousand such migrants settled in the region. The largest Dust Bowl communities formed in Bell Gardens, El Monte, and Lynwood, where agriculture and tire- and auto-manufacturing plants employed them. Smaller communities formed in Long Beach, Signal Hill, and Gardena, where many found employment in the oil and petroleum industry. Places like Glendale, Burbank, and Santa Monica attracted migrants looking to settle closer to work in airplane manufacturing. Many settled in unincorporated places in makeshift camps not unlike Mexican colonias.14 The Okie presence sparked racial tensions similar to those faced by African Americans, Asian Americans, and ethnic Mexicans. With a tenuous claim to whiteness, Okies drew unflattering comparisons with Mexicans. Journalistic representations during the 1930s often noted their lack of humility, labor skill, or cleanliness compared to their Mexican counterparts.15 For all the negative perceptions, Okies did not endure a mass repatriation regime. Okies in El Monte resented Mexicans from Hicks Camp and avoided interactions with them as much as possible, indicating that they believed themselves superior.16 As the Okie presence increased, the Mexican population decreased. The combined factors of the Great Depression and repatriation led to an estimated 30 percent drop in the local Mexican population.17

Despite the relative decline in the Mexican population, the spaces that they inhabited continued to draw harsh rebukes from civic and federal authorities. Appraisers for the HOLC regularly inserted subjective descriptions of communities of color to justify their low evaluations. Such perspectives reflected local anti-Mexican prejudices, the very kind that yielded both ethnically specific health quarantines and deportation campaigns.18 The city survey for the colonia of Jimtown on the edge of Whittier is a typical assessment of ethnic Mexican communities outside the city boundaries. Jimtown’s origins are obscure, but the proximity of walnuts, avocados, and oil suggests that its residents found employment in nearby industries. The HOLC evaluator “generously accorded [the community] a ‘low-red’ grade,” citing a 100 percent “foreign” population, all of whom were listed as “Mexican.” The appraiser noted that “many [were] American-born—impossible to differentiate.” This community of laborers, farmworkers, and Works Progress Administration (WPA) workers also faced the infiltration of “goats, rabbits, and dark skinned babies.” The housing construction was believed to be fifty years old or more and in terrible disrepair, and many buildings were identified as “hovels and shacks.” In addition, the appraiser noted that deed and zoning restrictions were lacking and concluded that “this is an extremely old Mexican shack district, which has been ‘as is’ for many generations. Like the ‘Army mule’ it has no pride of ancestry nor hope of posterity.” To add more injury to the insult of the evaluation, the federal appraiser described the colonia as a “typical semi-tropical countryside slum.”19 Designating Mexican spaces as slums evolved out of housing, public health, and social work investigations conducted throughout Los Angeles in prior decades. The linkage between race and space became an important marker of blight in the eyes of the state. Deemed by public health officials to be natural incubators of disease, Mexican spaces became primary targets for quarantine and surveillance. Indeed, citing an infiltration of “dark-skinned babies” served as a warning that the “Mexican problem” would extend well into the future.20

Such representations of Mexicans as perpetually foreign and inherently inferior resulted in continued segregation in underdeveloped neighborhoods. In the El Monte area alone, nine colonias housed over one thousand agricultural and industrial workers. Hicks Camp, Medina Court, Canta Ranas, La Misión, Las Flores, Chino Camp, Wiggins, La Granada, and La Sección comprised the El Monte “colonia complex.”21 Beyond El Monte were nearby colonias Pico, Jimtown, Simons Brickyard, La Puente, Rivera, Irwindale, and Rocktown, and a little farther away were the Whittier-area colonias of Carmenita, La Mirada, Los Nietos, and Flood Ranch. Each of these places contributed to a thriving blue-collar landscape that merged work and culture and represented a permanent home for many families who had fled Mexico in search of safety and stability.22 As outgrowths of a racialized society, most of these places struggled with persistent forms of racism, manifested in neglect of infrastructural needs by absentee landlords. Similar to working-class whites who had built their suburban ideal in places like South Gate, Cudahy, and Bell Gardens, ethnic Mexicans often built their own homes in these colonias.23 A report conducted by the Information Division of the Los Angeles County Coordinating Councils, funded by the WPA, cited extreme overcrowding and poverty as intertwined factors in arguing that the...