![]() I

I

MIGRATION![]()

1

Mexico and the United States

Steelworker and baseball player Gilbert Martínez moved to the neighborhood of South Chicago in 1926 at the age of sixteen. His journey to South Chicago started in 1914 when he and his family left Torreon, Coahuila, Mexico, in search of safety, work, and an escape from the Mexican Revolution. At the time, Torreon was the “railroad centre of the interior” where national and international rail lines connected. That made it an important strategic city, and one that was controlled by Pancho Villa’s Northern Army for much of the revolution. Although the exact date of Martínez’s departure from Torreon is unclear, major battles occurred in the area in April and December of 1914.1

Martínez’s father had been working in “some plant,” probably the large smelter just outside of town, when the fighting came through Torreon. Martínez, who was four years old when he left Torreon, does not talk much about the fighting, but he does remember the destruction. In a 1980 interview with the community leader Jesse Escalante, Martínez offered a succinct summary of the effects of the Mexican Revolution on hundreds of thousands: “Everything stopped and hardship.” The simplicity of Martínez’s statement belies the complexity of the universal devastation that caused everyday life and society to stop. People were threatened or killed for being on the “wrong side” in a revolution that had many armies and alliances. Work disappeared as the economy collapsed and people fled the chaos. The environmental devastation of war in the countryside severely limited food supply, adding an additional incentive to flee to those who were able. Although leaving Torreon was difficult, the Martínez family decided that the United States was their best option. Gilbert Martínez’s extended family, “the whole clan,” which included two of his uncles and their families, traveled to Cuidad Juarez in “those freight cars that carry sheep.” They crossed into El Paso. There the women and children lived while the men shipped out for seasonal work on railroad crews, although railroad companies occasionally allowed the whole family to travel with the crews and live in boxcars. Three years after arriving in El Paso, the Martínez clan moved on. They contracted with an enganchista, or labor agent, for work on the railroads at various locations in the Midwest. Gilbert Martínez and his immediate family ended up in Galesburg, Illinois, while extended family members ended up in Iowa and Missouri. After six years of summer visits to his sister in Chicago, Martínez and his immediate family moved to South Chicago.2

In the twelve years of their journey from Torreon to South Chicago, the Martínez family experienced several facets common to those who left Mexico and found their way to South Chicago.3 Although personal backgrounds and experiences varied greatly from person to person and family to family, generalizations are useful in examining overall migration patterns and illuminating how and why Mexicans entered this steel community. Tens of thousands—if not hundreds of thousands—left Mexico because of the economic difficulties created by the revolution. They hoped to find security, work, and a safe environment. Mexican men’s entry into the United States industrial labor force was overwhelmingly, but not exclusively, through positions on railroad maintenance crews as traqueros, or track workers.4 In fact, the first group of industrial, working-class Mexican men to enter the Chicago area came as traqueros under contract to various railroad companies extending or maintaining current railroad lines into the Chicago area. These contracts between Mexican workers and enganchistas on behalf of a railroad company commonly included transportation for the workers and their families to the worksite, usually charged to the new worker as an advance on wages. The first wave of Mexican migrants to the Chicago area started in 1916, a full decade before Gilbert Martínez’s move to South Chicago.5

Although 1916 was the year that Mexican laborers first entered the Chicago area in any significant number, it was the 1919 steel strike and Chicago race riots, the Mexican Revolution and Cristero Rebellion, as well as legislation that restricted immigration from outside the Americas that, separately and together, created conditions that favored the migration of large numbers of Mexicans to Chicago and the rest of the industrial Midwest. After the first wave of Mexicans began to establish communities, the routes that Mexicans and Mexican immigrants used continued to broaden. One South Chicago settlement house leader believed that by 1928, only 25 percent of Mexican immigrants entering Chicago came directly from Mexico. He credited the additional migration to those quitting railroad jobs, those who “drift in from a variety of employments,” and those who were “discontented farmworkers.”6

That same year, Anita Edgar Jones divided the Mexicans coming into Chicago into five general classifications: those brought directly by industry; those who worked their way north in easy stages, passing from one job to another, or from one division of the railroads to another; those who came directly to Chicago upon the advice of others who were there or had been there; those who came via the sugar beet fields of Michigan, Wisconsin, or Northern Minnesota; and those who were solos, or unaccompanied men who had no ties to the United States and were “seeking adventure.”7

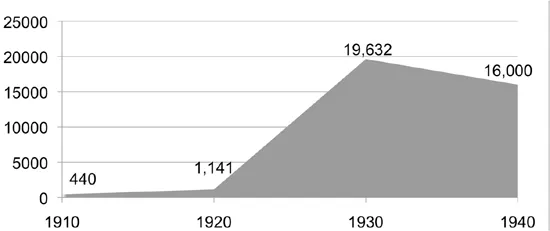

According to the United States federal census, Mexicans comprised 1,141 of the 808,558 foreign-born residents in the entire city of Chicago in 1920.8Other sources that did not differentiate between Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans listed the 1920 Mexican population of the city as 2,537. According to border records that indicate the intended destination of Mexican immigrants from 1920 to 1927, over 5,200 Mexicans listed Illinois as their final destination, with many of those undoubtedly bound for the Chicago area.9 Because of the lack of reliable data as to the numbers of Mexican immigrants to the United States, it is difficult to ascertain the number of Mexicans who crossed the border into the United States knowing that Chicago was their final destination. Regardless of declared intentions, the official 1930 Mexican and Mexican-American population of Chicago had grown to 19,632. By 1940, the post–Great Depression Mexican community had shrunk to around 16,000.10

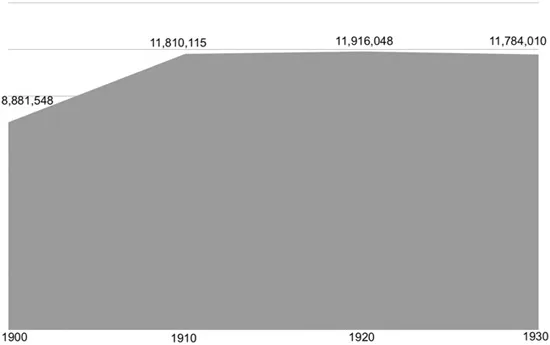

National numbers and percentages of European-born and Mexican-born immigrants demonstrate that South Chicago’s increase in Mexican population was part of a nationwide shift in immigration patterns. Although a few Mexicans already lived in the area before 1916, that year marked a turning point in the creation of a significant Mexican presence in the Chicago area. The outbreak of World War I in Europe caused a virtual end to European immigration to the United States, as able-bodied men were either occupied with fighting or unable to leave because of the disruption of war.11

Fig. 1.1. Mexicans in Chicago, 1900–1940.

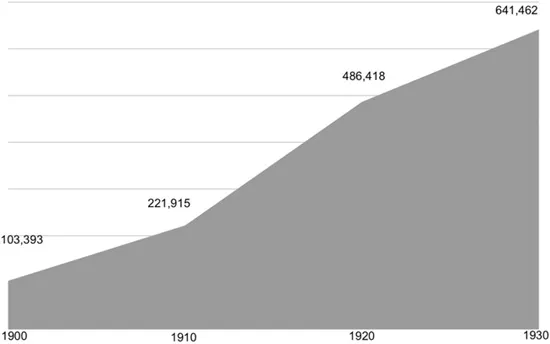

Fig. 1.2. Total foreign-born Mexicans in the United States, 1900–1930.

Fig. 1.3. Total foreign-born Europeans in the United States, 1900–1930.

In the first part of this study, I lay the foundation of the creation of a Mexican South Chicago by examining how and why Mexicans migrated there. I argue that various national and local factors shaped the patterns and timing of Mexican migration to the American Midwest in general and South Chicago specifically. In many cases, these factors directly affected the environmental conditions that awaited the newcomers along their journey and in South Chicago. The first chapter focuses on arguably the two largest, macro-level factors that shaped the timing and level of Mexican migration to the United States. The first of these was the revolutionary influence: the Mexican Revolution and the Cristero Rebellion prompted tens of thousands of Mexicans to migrate to the United States. The second factor was a result of restrictive U.S. immigration legislation that increased a labor shortage in the industrial Midwest: because Mexicans were exempt from these 1921 and 1924 quota laws, they became the default choice for employers who did not want to hire African Americans. In the following chapter, I focus on labor, labor agents, and racialized hiring practices. In the Chicago area, the demand for Mexican labor was accentuated by the race riots that immediately preceded the 1919 steel strikes. Racial tensions and the fears of some steel mill managers that hiring African Americans as strikebreakers would incite violence in South Chicago led to the recruitment and hiring of Mexicans. In short, revolution, riots, and race were significant factors in the migration of Mexicans to South Chicago.

Many early Mexican immigrants to South Chicago—those who came in 1916 through the 1920s—frequently cited the intertwined political, economic, social, and environmental repercussions of the Mexican Revolution as their impetus for leaving Mexico. Since the late nineteenth century, the United States has provided an escape-valve for Mexicans looking for opportunity and a possible break from economic despair.12 The devastating effect of revolution on everyday Mexican life is arguably the most prominent factor prompting the large exodus of Mexicans to the United States.13 War disrupted an already fragile agricultural economy, creating widespread environmental devastation, malnutrition, lack of work, and inflation. Many men volunteered to fight in one of the four principal armies of the Revolution of 1910, and many who did not want to fight fled to the United States fearing conscription. In addition, some fighters fled Mexico to avoid capture and conscription by advancing enemy armies. Civilians also feared for their lives as violence was not confined to the military battlefields.14

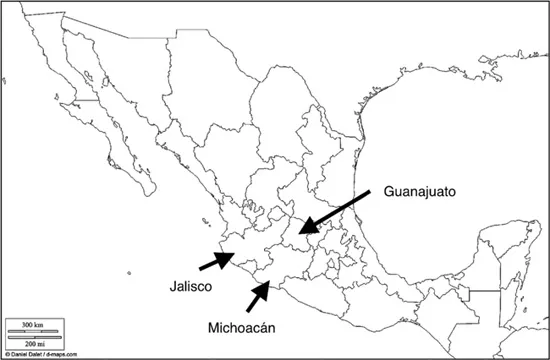

Although most of the fighting of the revolution ended by the time the United States entered World War I, continued unrest, including the Cristero Rebellion, caused turmoil in parts of Mexico throughout the 1920s. The Cristero Rebellion of 1926–1929 cost 90,000 lives (35,000 Cristeros and 57,000 government soldiers and anti-Cristero forces), and was fought in the rural states of Jalisco, Michoacán, Durango, Guerrero, Colima, Nayarit, and Zacatecas. Not coincidently, these states comprised the core sending states for Mexican migrants to Chicago. The uprising primarily involved rural peasants and their local priests protesting the federal government’s banning of the practice of Catholicism, including the celebration of mass and the administration of holy sacraments such as baptism and marriage.15 The fighting and long-term political and economic instability led a steady stream of immigrants to move northward to South Chicago throughout the late 1910s and the 1920s.16

The dead often leave families behind. Soldiers and civilians killed during the violence of the revolution were no exception. Pancho Villa’s army captured Serafín García’s father shortly after the Mexican federal army had drafted him in 1914. In order to stay alive, García’s father joined the Villista army and fought for two years. After returning to his job in a bakery, he was executed by soldiers of yet another revolutionary army, this time serving Venustiano Carranza. Serafín García, his mother, brothers, and some extended family fled the chaos of the Mexican Revolution in Guanajuato for Texas. They left a country at war and in social and economic disarray for the promise of a new life in the United States. After six years of farm work and odd jobs in Texas, and a season as betabeleros, or sugar-beet pickers, in Ohio, the García family settled in South Chicago.17 García’s mother left revolutionary Mexico with no intention of settling in the U.S. Midwest, but she, along with her children, eventually made their way to South Chicago and became active members of its Mexican community. García’s family is an example of another route into the urban South Chicago Mexican community, through Midwestern farm work.

For many Mexican immigrants in South Chicago during the 1910s and 1920s, regardless of whether they migrated directly to South Chicago or moved there after first living in other parts of the United States, the economic chaos related to the Mexican Revolution was the leading macroeconomic factor that prompted many to consider migration.18 A 1925 survey sponsored by the City of Chicago found that over half of the heads of households surveyed were from three central Mexican states: Guanajuato, Michoacán, and Jalisco. These three states were severely affected by fighting during the revolutionary period of 1910–1920, and bore the brunt of the violence during the Cristero Rebellion.19 This demographic pattern held throughout the interwar period. By 1936, 63 percent of South Chicago Mexicans came from these same three states. The remaining 37 percent came from the Distrito Federal, the district that encompasses Mexico City, and nineteen other states.20

Fig. 1.4. Outline map of Mexico highlighting the three states sending the majority of Mexican immigrants to the Chicago area.

Although conditions in Mexico caused many to migrate, the U.S. Immigration Acts of 1921 and 1924 were important pull factors in the continuing demand of Mexican workers in post–World War I South Chicago industry. Concerned that the end of World War I would lead to a surge of “undesirable” immigrants from eastern and southern Europe, Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1921. The law restricted immigration in any given year to 3 percent of the total number of foreign-born immigrants of each nationality residing in the United States as determined by the 1910 federal census. Because of the large number of foreign-born Mexicans already in the United States by 1910, the 1921 law allowed for the legal entry of a large number of Mexicans.

The Immigration Act of 1924, also known as the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, reduced the quota from 3 to 2 percent of any nationality as recorded in the 1890 federal census. This change was directed at limiting eastern and southern European immigration while benefiting the more favored immigrants from northern and western Europe. In Impossible Subjects, historian Mai Ngai argues that the 1924 law demonstrated a shift from a cultural understanding of nationality to one determined by race. With the 1924 law, white Protestants descended from northern Europeans attempted to maintain their control of mainstream American society and culture.21 Residents of Canada, the Canal Zone, and independent American countries were “nonquota” immigrants exempted from the limits for diplomatic and economic reasons. The exemption of Mex...