- 497 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This intimate biography of the pioneering Texas governor is "required reading for political junkies—and for women considering a life in politics" (

Booklist).

When Ann Richards delivered the keynote of the 1988 Democratic National Convention and mocked President Bush—"Poor George, he can't help it. He was born with a silver foot in his mouth"—she became an instant celebrity and triggered a rivalry that would alter the course of history. In 1990, she won the governorship of Texas, becoming the first ardent feminist elected to high office in America. Richards opened pathways for greater diversity in public service, and her achievements created a legacy that transcends her tenure in office.

In Let the People In, Jan Reid offers an intimate portrait of Ann Richards's remarkable rise to power as a liberal Democrat in a deeply conservative state. Reid draws on his long friendship with Richards, as well as interviews with family, personal correspondence, and extensive research to tell the story of Richards's life, from her youth in Waco, through marriage and motherhood, her struggle with alcoholism, and her shocking encounters with Lyndon Johnson and Jimmy Carter.

Reid shares the inside story of Richards's rise from county office to the governorship, as well as her score-settling loss of the governorship to George W. Bush. Reid also describes Richards's final years as a mentor to a new generation of public servants, including Hillary Clinton.

When Ann Richards delivered the keynote of the 1988 Democratic National Convention and mocked President Bush—"Poor George, he can't help it. He was born with a silver foot in his mouth"—she became an instant celebrity and triggered a rivalry that would alter the course of history. In 1990, she won the governorship of Texas, becoming the first ardent feminist elected to high office in America. Richards opened pathways for greater diversity in public service, and her achievements created a legacy that transcends her tenure in office.

In Let the People In, Jan Reid offers an intimate portrait of Ann Richards's remarkable rise to power as a liberal Democrat in a deeply conservative state. Reid draws on his long friendship with Richards, as well as interviews with family, personal correspondence, and extensive research to tell the story of Richards's life, from her youth in Waco, through marriage and motherhood, her struggle with alcoholism, and her shocking encounters with Lyndon Johnson and Jimmy Carter.

Reid shares the inside story of Richards's rise from county office to the governorship, as well as her score-settling loss of the governorship to George W. Bush. Reid also describes Richards's final years as a mentor to a new generation of public servants, including Hillary Clinton.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Let the People In by Jan Reid in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Gardens of Light

Portrait of Ann Willis as a Waco teenager, about 1950.

CHAPTER 1

Waco

The studio photograph of Ann Willis was probably taken in 1950, when she was seventeen. Born September 1, 1933, she answered to Dorothy or Dorothy Ann until her family moved into the small city of Waco from an outlying country town at the start of her high school years; she decided then that she liked her middle name more. A gangly teenager, Ann wasn’t beautiful in all her pictures at that age. She printed a large, self-conscious “me” above her unflattering photo in her senior yearbook at Waco High, though elsewhere in the annual she was afforded a full-page airbrushed photo as the school’s most popular girl. She had worked at gaining that popularity and being a model student. She and a partner won two state championships in girls’ team debate, and as a delegate of a civics youth organization called Girls Nation, she got to go to Washington and shake President Harry Truman’s hand in the White House Rose Garden.

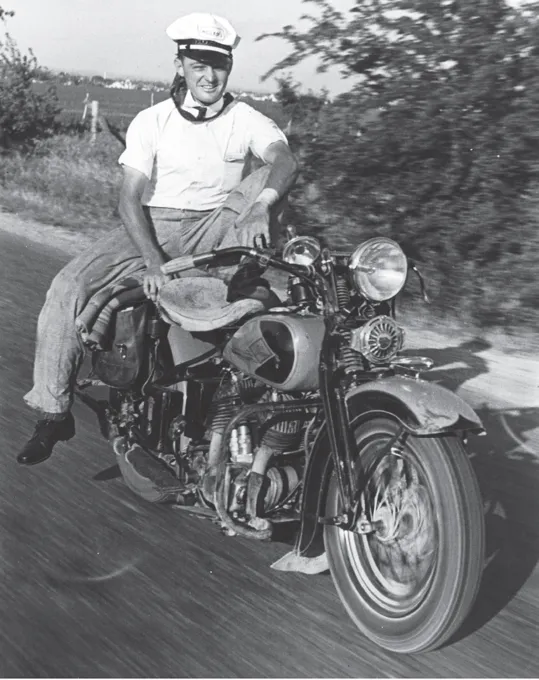

But the best portrait of her that year was taken in the studio of her uncle Jimmie, a shutterbug and popular figure in Waco. He raced about town on a big motorcycle, wearing the style of cap popularized by Marlon Brando in the movie The Wild One. The awkward kid was now a lovely young woman. In the photo, she wears a light sweater over her blouse and a pair of short earrings. Her short brown hair is styled in a relaxed wave over her brow, curling over her temples and ears and nape of her neck as she looks back over her shoulder. The blink of the camera lens captured the beginning of a smile and an elegant pair of eyes—her prettiest feature—and a frank and mischievous glance. One could see the glint in those eyes already. One part of her was a born hell-raiser.

Ann may have inherited her affection for motorcycles from her uncle Jimmie Willis, a popular news shutterbug and studio photographer in Waco in the 1940s and early 1950s. Ann believed she received her first newspaper board endorsement in Austin in 1976 because of a newspaper editor’s affection for her uncle.

Ann didn’t exaggerate much when she said the people she came from were dirt poor. All four of her grandparents were raised on Central Texas tenant farms. Her father, Cecil Willis, came from a community called Bugtussle. In the version of events that Cecil passed along, Bugtussle got its name from a Baptist camp revival in which people from miles around circled up their wagons, built fires, put their children down after supper on piles of quilts and blankets—hence the evocative expression “a Baptist pallet”—and spent the evenings praising the Lord and singing hymns. When night fell on the camp revival, a fellow whose last name was most likely Bugg switched sleeping children from wagon to wagon as a practical joke that was not funny; it set off a panic and brawl. The farming hamlet of Bugtussle soon dwindled away. Cecil Willis had to quit school after he finished the eighth grade. He got a job delivering pharmaceuticals to drugstores for a salary of $100 a month.

Iona Warren was born near another farming hamlet, also now extinct, called Hogjaw, but she and two sisters grew up in the community of Hico. Iona, who finished the eighth-grade schooling available to her, found work in Waco as a sales clerk in a dry-goods store. On a blind date, Cecil took Iona to a picture show; when the projector broke down, they were given a rain check, which guaranteed another date. They soon married. They paid $700 for an acre of land and built a little house in the burg of Lakeview. The town’s name must have referred to the summer’s heat mirage; there was no lake close around.

Ann’s parents were poor enough that at times they feared hunger. Cecil’s family had once come into possession of a field of tomatoes, and his mother canned them all. For the rest of his life, Cecil couldn’t stomach stewed tomatoes. Chickens, a major source of their protein, were just that to Iona—food that walked around. Dorothy Ann was born in a bedroom of their house in the hardest year of the Depression, following labor protracted enough that the attending doctor sighed and made himself a pallet on the front porch. The baby arrived at six in the morning. Iona had asked a neighbor woman to cook Cecil’s supper the evening after Ann was born, but the neighbor couldn’t stand to kill a chicken, so Iona had to wring the chicken’s neck and watch it flop and bleed all over the floor because she did not have the strength to rise from the birthing bed.

Cecil got his World War II draft notice at the age of thirty-five. Ann was nine years old; it was the first time she could remember seeing her strapping daddy cry. He went through navy boot camp and pharmaceutical school in San Diego, where he was stationed the rest of the war. The company that had employed Cecil gave Iona a job, but after a few months she decided to take their daughter and join him. Before taking off on the long highways across the southwestern desert, Iona wrung the necks of every chicken they owned, plucked them in stinking hot water, then cut them up, stewed them, and preserved them in quart jars. She assumed they were going to be hungry and short of money. Cecil later said that when they drove up, they looked like characters in The Grapes of Wrath.

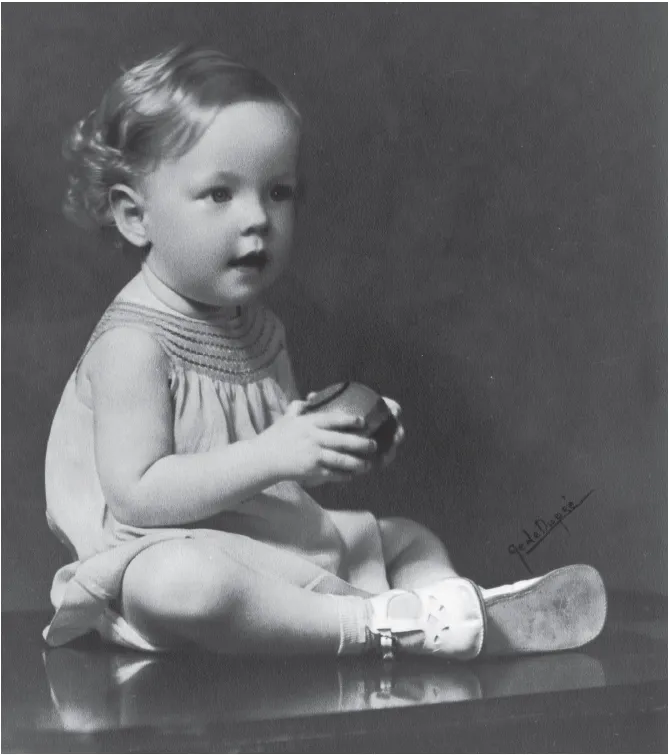

Studio portrait of the infant Dorothy Ann Willis, Waco, 1934.

Housing was so scarce in San Diego that for a while they all slept in a cramped basement room. Iona lost a baby in a traumatic pregnancy during the less than two years they were in California. But for Ann, it was a thrilling time of riding a bus and streetcar to a large junior high school in the center of the city. There were verdant hills and palm trees. Shifts in the ocean breeze carried songs of the nation’s warriors as they put in their miles doing double time; giant warships in the harbor moved across the horizon. San Diego had a powerful effect on the skinny girl from Texas. She reminisced in her book, “This was my first exposure to kids who were Italian and Greek and black and Hispanic.” Yet she didn’t get to make the kind of friendships that would have allowed her to roam the neighborhoods and spend the night at other girls’ homes. Her parents feared having an eleven-year-old girl out on streets that were full of sailors and marines.

When the war ended, they moved back to the house in Lakeview. They had hunting dogs, some years they fattened and slaughtered a pig, and Dorothy Ann’s daddy took her fishing all the time. She loved to tell a story about a junior high school basketball game against Abbott, a rival school where Willie Nelson was one grade behind her. As she prepared to shoot a free throw one night, an Abbott boy hollered, “Make that basket, birdlegs!”

Iona and Cecil had made up their minds that their daughter would get the best education possible, and they wanted her exposed to more prosperous and sophisticated people in high school. Cecil had risen from driver to sales representative for the pharmaceutical company. He and Iona worked hard and saved well, and on the north side of Waco they managed to build a home that had a den and a living room with a fireplace, bedrooms situated at each end of the house, and that feature of postwar middle-class status—a picture window.

For Ann, Waco proved to be one of those hometowns that declined to let go. Founded in 1849, the town got its name from a band of Indians who were part of the Wichita confederation and camped along the Brazos, the most Texas of rivers. Long after the Huecos (Wacos) were expelled to cultural oblivion in Oklahoma, the town had a genuine cowboy element: forty-five miles upriver, the Chisholm Trail crossed the Brazos at a low-water spot called Kimball Bend. The river carved a tortuous horseshoe bend of more than a dozen miles to come back within a mile of that ford. Once the drovers got the cattle across the Brazos, they had to herd them hard to keep them from falling off tall cliffs at a place called Broke Rock, taking horses and riders with them.

As Waco grew, its most distinctive attribute became Baylor University. Originally opened in Independence, Texas, in 1846, Baylor was consolidated with Waco University and moved to its present location in 1886; it became the largest institution of higher learning supported by the Southern Baptist Church. Not everyone in Waco subscribed to those beliefs, and perhaps the most durable aspect of Waco’s lore—the story that everyone raised there has heard told again and again—concerned Baylor’s role in a gunfight that erupted downtown in broad daylight in 1898. Waco was the adopted home of a famous newspaperman, William Cowper Brann. Following the death of his mother in 1857, Brann, the son of a Presbyterian minister, was placed in the care of a farm couple named Hawkins in Coles County, Illinois. After running away at thirteen, and with only three years of schooling, he learned the journalistic craft in half a dozen American cities. At one point, he sold his newspaper, the Iconoclast, to Austin’s William Sydney Porter, the short-story writer, embezzler, and ex-convict who took the pen name O. Henry. Brann bought the paper back and in Waco wrote screeds about Baptists, Episcopalians, Englishmen, Negroes, and New York City elites: “Sartorial kings and pseudo-queens . . . [who] have strutted their brief hour upon the mimic stage, disappearing at daybreak like foul night-birds or an unclean dream—have come and gone like the rank eructation of some crapulous Sodom . . . a breath blown from the festering lips of half-forgotten harlots.”

Even by the yellow-journalism standards of the day, Brann’s prose was sure to make its targets furious. His attacks on Baptists and Baylor University reached fever pitch in the last years of the nineteenth century. In an 1898 exposé, Brann claimed that Baptist missionaries were smuggling South American children into the country and making them house servants—tacit slaves—of Baylor officials. He alleged that a relative of the university’s president had gotten a Brazilian student pregnant, that professors seduced female students as a matter of course, and that any father who sent a daughter to Baylor was risking her disgrace or rape. The college, he wrote, was nothing but a “factory for the manufacture of ministers and magdalenes.” The slur was drawn from the centuries-old character attack on Jesus Christ’s follower Mary Magdalene—magdalenes were reformed prostitutes.

Tom Davis, a prominent Baylor supporter and the father of a Baylor coed, was so enraged that he and another man fired on Brann as he walked on a downtown street. Brann the Iconoclast, as he was known, also carried a gun. He drew his pistol and flung off several shots, mortally wounding Davis and putting him down in the doorway of a cigar store. But a bullet fired by one of the assailants tore through Brann’s lung. Waco police made him walk to the city jail, though friends were later allowed to carry him to his home. He died the next morning at the age of forty-three.

For many years, the town run by Baptists had a thriving red-light district. In 1916, a black teenager named Jesse Washington was convicted of murdering a white woman in Waco; a mob tortured, mutilated, and burned him to death as police withdrew and a crowd of 15,000 watched the lynching, which was condemned around the world as the Waco Horror. When Cecil Willis and Iona Warren found their first jobs there, members of the Ku Klux Klan dominated local politics and law enforcement. But the town’s reputation and legacy were not all hypocrisy and violence. In 1885, a pharmacist named Charles Alderton, who was employed by Morrison’s Old Corner Drug Store, had started fiddling with the recipe of a sweet syrup that the soda jerks mixed with carbonated water—the secret ingredient was rumored to be prune juice. The name “Dr Pepper” grew out of an ad pitch that the drink would pep you up during the day if you refreshed yourself with one at ten, two, and four o’clock. But when people were drinking their favorite beverage fresh made at Old Morrison’s Corner Drug Store, they simply said, “Let me have a Waco.”

Rich people lived on Waco’s west side. One of those families had arrived in Central Texas in uncommon fashion. In 1926, Dick “Cul” Richards was a World War I navy veteran whose roots were in Iowa, but he got an offer to become the freshman football coach at storied Clemson University. A fellow coach assured Richards that would be a very good offer to accept. Dick Richards’s wife, Eleanor, was tall, broad-shouldered, and assertive. She came from an Iowa family that owned a major seed company and, in the misfortune of those times, some banks that had failed. She had a degree from Grinnell College in Iowa and had started graduate work at Radcliffe before the collapse of her family’s finances. The couple moved to South Carolina, and in the spring of ’26, Cul coached the Tiger baseball team to a record of eight wins and eleven losses. When training for the football season began in August, he was the coach of the freshmen and an assistant with the varsity, but in October the head coach abruptly quit. Richards and another coach were charged with keeping the team together and salvaging the season. The regime lasted two weeks. According to his wife, Richards became so overwrought during his coaching finale that alarmed trainers and doctors packed him in ice, fearing he might die. Dick Richards recovered from the coaching experience and got a sensible degree at Clemson in construction engineering. He was helping build a highway in Texas when the large company that employed him went broke. He and Eleanor were literally stranded in Waco. Their only son, David, was born there in 1933.

Papa Dick, as he came to be known in the family, first found work with a small hardware store and then managed to buy it. Despite his age, he talked his way back into the army in World War II, and when he came back home, the fruits of victory and the clout of Texas’s congressional leaders had bestowed on the small city an army flying school and the Blackland Army Air Field, and nearby is the army’s vast Fort Hood. Using his knowledge and experience as an engineer, he made the hardware store into Richards Equipment Company, which supplied machinery and parts used in road building and other heavy construction. Papa Dick won bids for a sizeable number of military construction projects.

He built the family a large house near the golf course—golf became his athletic obsession after his ill-starred coaching career. The house had leaded glass windows, a brass fireplace, and antiques throughout. Eleanor Richards, nicknamed Mom El, did not adapt as well to life in Waco. Thinking she would finish her graduate degree, she applied at Baylor; the hierarchy of Baptist academics informed her that Baylor would not recognize the credits she had accumulated at Radcliffe. That institution, they ruled, was nothing more than an effete girls’ finishing school, even if it was an affiliate of Harvard University. Contemptuous of such provincialism, Eleanor founded the Waco League of Women Voters and was later a president of the state organization. She expected her son to carry on the family trait of self-reliance. David was terrified as a small boy when his mother put him on a train to go visit relatives in Iowa. It was up to him to negotiate the transfer in the sprawling train station in St. Louis.

Dissatisfied with the quality of public education in Waco, or at least with the way her son took to it, Mom El dispatched him for his junior year to Andover, the famous prep school in a 300-year-old community in the Boston area. One time when David was home, his mother was reading the newspaper and saw a story and photograph about Ann Willis’s trip to Washington as a Texas delegate to Girls Nation. The photo of the delegates showed Ann sitting next to a black girl. In Waco, that probably aroused more comment than her shaking the hand of Harry Truman. On that trip, Ann gained an enduring friend in the granddaughter of Coke Stevenson, the Texas governor who lost the notorious 1948 Democratic runoff for the U.S. Senate to Lyndon Johnson by a fortuitously discovered, and probably fraudulent, eighty-seven votes. Eleanor wondered aloud why her son could not get interested in a smart girl like that? David doubtless gave his mother the silence or harrumph the remark deserved.

Ann said the best part of her high school experiences began the day in 1949 when she met the tall, handsome, and jocular young man who had spent a year at Andover and had then come back for his senior year at Waco High. In her memoir, Straight from the Heart: My Life in Politics and Other Places, written with the help of Peter Knobler, she reminisced, “The A&W Root Beer stand was the local summer hot spot. You’d pull up in your car and they would come out and put a tray on your window, and you’d sit and talk and kids would come over. David was sitting at the A&W when I met him. . . . I thought he was just the nuts.”

He took her out to dinner on their first date following her performance in a school production of Noel Coward’s Blithe Spirit. She had never been around people who ate shrimp; she doubted that she had been in a real restaurant more than half a dozen times in her life. She carefully ordered what he did. As their senior year wore on, they became inseparable. Ann loved the way conversation just took off when she was with him. He had strongly held positions on social matters that most young people their age had not even considered. An English teacher at the high school remarked one day that he had the biggest vocabulary in her class. The praise won him endless razzing from their crowd of friends. “There he goes,” they hooted when he embarked on some lofty statement of principle. Though he had little notion of where his beliefs might lead, David was an idealist. Inspired by his parents’ reading of a story that never got old, he chose for his moral compass a rogue with a conscience and a sense of justice. Ann recalled, “Robin Hood, Little John, Friar Tuck, Maid Marian, Alan-a-Dale—the characters became personal friends of David’s. Intimates. He lived in that world. . . . We would talk about it all the time; it was a recurring theme: ‘What would Robin Hood have done?’”

Going steady with David ushered Ann into a milieu she had never known before. His family traveled, subscribed to magazines like the New Yorker and the New Republi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue: Glimpses

- Part One: Gardens of Light

- Part Two: Superwoman’s Chair

- Part Three: Only in Texas

- Part Four: The Parabola

- Epilogue: Passages

- Notes

- Photo Credits

- Index