- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Introducing a new model for the transnational history of the United States, Raúl Ramos places Mexican Americans at the center of the Texas creation story. He focuses on Mexican-Texan, or Tejano, society in a period of political transition beginning with the year of Mexican independence. Ramos explores the factors that helped shape the ethnic identity of the Tejano population, including cross-cultural contacts between Bexareños, indigenous groups, and Anglo-Americans, as they negotiated the contingencies and pressures on the frontier of competing empires.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Beyond the Alamo by Raúl A. Ramos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia de Norteamérica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Three Worlds in 1821

Chapter One

Making Mexico

INSURGENCY AND SOCIAL ORDER IN BÉXAR

Each citizen becomes a worker, each worker a soldier, and each soldier a hero that is worth a hundred ordinary soldiers.

On September 27, 1821, military officials in Béxar lowered the Spanish flag flying over the presidio in Béxar and raised the Mexican flag in its place.1 The solemn and orderly transfer belied the contentious and often violent rebellion, known as the insurgency, of the preceding decade. On two separate occasions, in 1811 and 1813, insurgents and royal troops had clashed in and around Béxar, affecting the lives of people in the entire region. While the insurgency in Béxar had links and parallels to the greater independence movement in Mexico, it also took on distinctive local characteristics. Those differences stemmed from Béxar’s location in the Mexican borderlands and the town’s social order, based on Spanish notions of prestige. The year 1821 marked the start of a new period for Bexareños as citizens of the Mexican Republic, even while they continued the colonial social order based on family prestige.

The transition in 1821 is important not just for the change in official national identity but also because of the decade of turmoil that preceded it, starting with the rebellion in 1811. That period of violence revealed elements of the town’s social order and the underlying connection between local culture and incipient nationalism. But larger questions remain: what explains Bexareño decisions to support either the insurgency or the Crown or to avoid conflict altogether? To understand Bexareño choices requires an analysis of the extent of dissatisfaction with Spain, the incentives encouraging independence, the decreased barriers to rebel, and internal support for the insurgency. While insurgency provided ideological support for independence on a national scale, local concerns shaped the protests raised by Tejanos and the form of their protest.

The Tejano social order based on family and prestige drove the local response to independence in Béxar. Individuals from the Navarro, Veramendi, and Ruiz families participated in the insurgency for a variety of reasons, from economic to ideological. A brief look at their involvement in this period leading to independence in 1821 illustrates to what extent the insurgency was largely a family affair. José Antonio Navarro joined the rebel cause, as did his uncle Francisco Ruiz.2 Forty years later, Navarro wrote about this period, noting, “[Mexicans] did not understand the reasons for the rebellion of the priest Hidalgo as [anything] other than a shout for death and war without quarter on the gachupines, as the Spaniards were called.”3 Another participant in the rebellion, Juan Martín de Veramendi, married José Antonio’s sister, Josefa. Yet these family ties did not easily translate to political affiliation, as the royalist defenders included José Antonio’s brother José Angel Navarro.4

Two local issues in particular became important at this point and continued to shape Béxar’s history after 1811. The first was the social structure informing action and power in the town. The structure itself can be understood through the acquisition of prestige by elite families to maintain their influence and status in the town. Second, Béxar’s location on the borderlands placed pressures on its citizens that were different from those experienced by Mexicans in other regions. Proximity to the United States and to indigenously controlled territories fueled the rebellion while raising the stakes of its outcome. Tejanos became skilled at navigating between these borderlands communities and eventually used those interactions as a means to build family prestige within Béxar. This chapter uses the two very different rebellions in 1811 and 1813 as a window into the Bexareño social world and its connection to early Mexican national identity. The two rebellions followed a trajectory connecting established social foundations, defined by prestige, with new cross-cultural relations to Anglo-Americans and indigenous peoples. The 1811 rebellion revealed elements of the existing social hierarchy and the tense relationship between frontier Mexicans and the Spanish Crown. The 1813 rebellion added a layer of ethnic contact, since Anglo-Americans participated in the battles and many Bexareños relied on indigenous support after the war. These developments along the lines of prestige and cultural contact established patterns and practices that shaped the history of the region from independence in 1821 and beyond.

The movement for Mexican independence in the northeast revealed both the nature of region in relation to the rest of the nation and some differences of opinion on how to achieve independence. Insurgent activity produced few large battles in the northeast provinces of New Spain. Nevertheless, differences with royalist officials and peninsular natives living in the region created deep animosity and fueled the movement in the Provincias Internas de Oriente. The insurgency laid the groundwork for the northern region’s inclusion in the Mexican nation, despite its often tense and exploitative relation with Mexico City. Mexican independence in 1821 extended the reach and power of the nation-state right up to the northern borderlands. Violence during the early insurgent years demonstrated Spain’s tenuous domain over these frontier areas.

Attempts to understand Mexican independence as a broad national movement have failed to explain the diverse development and operation of the insurgency in each region. Father Miguel Hidalgo’s initial drive to create a broad-based rebellion among the peasantry faltered as he left the Bajio region on the way to Mexico City.5 In some areas, such as San Luis Potosi, royalist elites received extra support from rural villagers during the insurrection. Hidalgo never raised a unified revolt under a single ideology in his actions of 1810–11. Instead, the insurgency became a protracted war fought on many fronts and for a variety of reasons. Recent historians have turned to studies of the provinces of Mexico to understand the dynamics of the insurgency and Mexican independence.6 Events in Béxar and Texas add a unique element to those regional case studies by introducing the border to the insurgency.

Northern Insurgency: Casas in 1811

Every morning, the people of Béxar awoke to the sound of reveille assembling the troops of the presidio.7 But on the morning of January 22, 1811, secret plans disrupted the daily routine as reveille instead signaled the start of an insurgent plot to arrest the Spanish governor, Manuel Salcedo, and the military commander, Lieutenant Colonel Simon Herrera, and assemble the soldiers under new leadership. Juan Bautista de las Casas, a retired military officer, took control of those troops and declared himself and Béxar under the command of the newly formed Insurgent Army of America. Two town leaders, the heads of two local elite families, marched alongside Casas on the way to free insurgent messengers from the Alamo prison: Gaspar Flores and Francisco Travieso, the alcalde (or mayor) of Béxar. Flores and Travieso’s presence gave legitimacy to the coup in the eyes of Bexareños and signaled the deep ambivalence many Tejanos felt about their allegiance to the Spanish Crown.

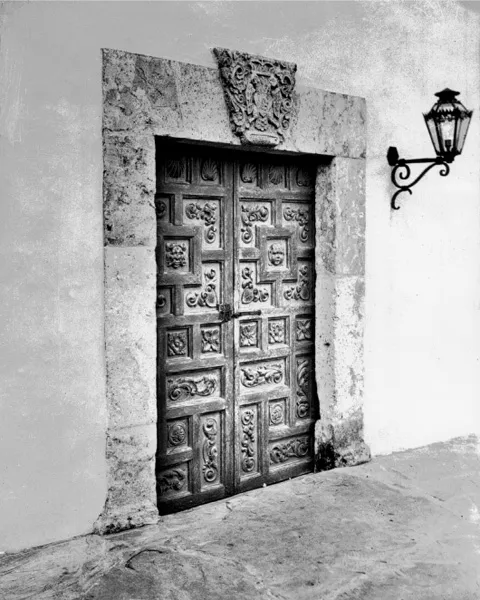

The Spanish Governor’s Palace door after restoration, 1930. (San Antonio Light Collection, UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures, No. 1037-I, courtesy of the Hearst Corporation)

Travieso recounted his observations of and involvement with Casas and the revolt of 1811 during Casas’s trial for high treason. According to Travieso, the soldiers and citizens of Béxar believed rumors that Salcedo and Herrera planned to permanently relocate troops stationed in town to Río Grande, abandoning the defense of Texas and leaving it open to attacks from Indians and Anglo-Americans. Travieso mentioned that “the citizens were equally obliged to render services in the defense of their country; . . . it would be a strange thing, that others from elsewhere were defending their country while the natives looked on indifferently in the case that affected them much more.”8 Travieso’s opinion revealed the strong local interests motivating the actions of insurgents in Béxar. During the trial, Travieso claimed that his actions served to aid the colony, Crown, and church by protecting Béxar and Texas from Indians and foreign invaders. Travieso also believed his actions were required to protect the settlers in Texas. As a result, he and other insurgents imprisoned royal authorities and confiscated their property. While Travieso may have obscured some of the reasons for participating in the rebellion for fear of incriminating himself before the government tribunal, his statement underscored the local motivations that influenced many participants in the insurgency in Béxar and in other parts of northeastern Mexico. In this case, the threat of indigenous attacks motivated the rebellion in part.

Before Casas had initiated his revolt, news of Father Hidalgo’s proclamation of independence and armed uprising against Spain had reached the northern provinces of New Spain, the Provincias Internas, soon after the Grito de Dolores, Hidalgo’s declaration from a church bell tower on September 15, 1810. Hoping to cut off support for the rebellion early, Governor Salcedo called on the inhabitants of the Texas capital to publicly declare their allegiance to the Crown and to their religion.9 Salcedo attempted to dispel rumors of abandoning Texas and listed the successes of the Spanish government. But unrest continued to spread in the northeast and in Béxar, primarily through the efforts of former military officer Mariano Jiménez. With close ties to Hidalgo, Jiménez organized the insurgent movement in the northeast, from San Luis Potosi northward to the four provinces.10 Salcedo arrested two alleged agents of Jiménez’s plotting to spread the revolution to Béxar. Soon after his coup, Casas moved rapidly to ally with Jiménez as he took control of Béxar.

Jiménez’s insurgency occupied several major cities in northeastern Mexico, including Saltillo and Monclova. As Hidalgo and his collaborator Ignacio Allende’s losses began to mount in central Mexico, they grew increasingly dependent on the base Jiménez built in the north as an escape to regroup for a later attack. But the inhabitants of northern Mexican towns provided tepid support for the insurgency and likewise provided little resistance to the counterinsurgency that would crush Jiménez and Hidalgo. Insurgent occupation of Béxar provided a crucial link to weapons and mercenary manpower from the border with Louisiana. In this way, the location in the borderlands served both as a resource and as an escape valve for the rebellion, giving the insurgency unique significance in the northern provinces.

Casas’s occupation of Béxar lasted for only a short period, from January 22 to March 2, 1811, but his actions brought inhabitants from the northeastern reaches of the Mexican frontier into the national struggle for independence from Spain. Subdeacon Juan José Zambrano led the counterrevolt against Casas in Béxar, using a variety of emissaries to aid the resistance against the wave of insurgent activity in northeastern Mexico. The reestablishment of royalist government in the provinces culminated in an ambush at the Wells of Bajan on March 21, where Jiménez, Hidalgo, and Allende were captured. While the rebellion appeared to be a small skirmish in the larger insurgency, these activities on the northern frontier brought Spanish attention to the potential support insurgents could gain from the connection to the American frontier.11

While the actions of the Spanish military commanders in the north quelled the first flash of insurgent revolt in Mexico, unrest continued in the region, albeit in a less organized fashion. Again, Béxar served as the main site for rebel activity. And once again, members of the Travieso family played a role in the rebellion. This time, the participants in the second rebellion, two years later in 1813, availed themselves of the region’s economic and political advantages to an even greater extent. In turn, increased numbers of Bexareños now put their lives and futures on the line for the chance to establish an autonomous government.

Casas’s revolt in 1811 might appear as a footnote in Hidalgo’s larger insurgency movement, yet it also served as a crucial first step that expressed displeasure with specific officials or policies of the Spanish government affecting Béxar.12 Many features of Casas’s actions give the impression that the revolt was primarily a dispute between military commanders. The lack of direct, active participation by the citizens of Béxar precludes calling these events part of a larger social revolution. While Casas set out to confiscate the property of Europeans in Béxar, his revolt lacked any stated ideology and never attempted to restructure society in a comprehensive way.

Nevertheless, the readiness of Bexareños to revolt against royal government officials suggested a growing sense of dissat...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Beyond the Alamo

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations, Tables, Figures, and Map

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Prologue

- Part I Three Worlds In 1821

- Part II Becoming Tejano

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index