eBook - ePub

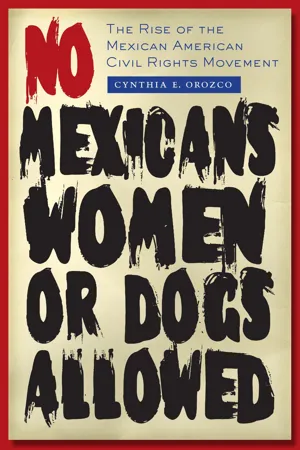

No Mexicans, Women, or Dogs Allowed

The Rise of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement

- 330 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

No Mexicans, Women, or Dogs Allowed

The Rise of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement

About this book

"A refreshing and pathbreaking [study] of the roots of Mexican American social movement organizing in Texas with new insights on the struggles of women" (Devon Peña, Professor of American Ethnic Studies, University of Washington).

Historian Cynthia E. Orozco presents a comprehensive study of the League of United Lantin-American Citizens, with an in-depth analysis of its origins. Founded by Mexican American men in 1929, LULAC is often judged harshly according to Chicano nationalist standards of the late 1960s and 1970s. Drawing on extensive archival research, No Mexicans, Women, or Dogs Allowed presents LULAC in light of its early twentieth-century context.

Orozco argues that perceptions of LULAC as an assimilationist, anti-Mexican, anti-working class organization belie the group's early activism. Supplemented by oral history, this sweeping study probes LULAC's predecessors, such as the Order Sons of America, blending historiography and cultural studies. Against a backdrop of the Mexican Revolution, World War I, gender discrimination, and racial segregation, No Mexicans, Women, or Dogs Allowed recasts LULAC at the forefront of civil rights movements in America.

Historian Cynthia E. Orozco presents a comprehensive study of the League of United Lantin-American Citizens, with an in-depth analysis of its origins. Founded by Mexican American men in 1929, LULAC is often judged harshly according to Chicano nationalist standards of the late 1960s and 1970s. Drawing on extensive archival research, No Mexicans, Women, or Dogs Allowed presents LULAC in light of its early twentieth-century context.

Orozco argues that perceptions of LULAC as an assimilationist, anti-Mexican, anti-working class organization belie the group's early activism. Supplemented by oral history, this sweeping study probes LULAC's predecessors, such as the Order Sons of America, blending historiography and cultural studies. Against a backdrop of the Mexican Revolution, World War I, gender discrimination, and racial segregation, No Mexicans, Women, or Dogs Allowed recasts LULAC at the forefront of civil rights movements in America.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access No Mexicans, Women, or Dogs Allowed by Cynthia E. Orozco in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9780292774131Subtopic

North American HistoryPART ONE

SOCIETY AND IDEOLOGY

The Mexican Colony of South Texas

ONE

The horizon of life for the Mexican American, especially in Texas, was dark and dreary. The skies, during the early twenties were menacing; the clouds were fraught with racial discrimination, threats, and economic slavery. . . . Strong tributaries constantly flowing into a river of hate and disdain; almost reaching flood proportions were the public signs along the public highways in front of restaurants: “No Mexicans Allowed.” So there were no movies, no barbershops, no swimming pools, no jury service, no buying of real estate, no voting, no public office.

—M. C. GONZÁLES, LULAC NEWS, 1974

This story begins in South Texas. In the 1910s and 1920s industrialization, urbanization, and the rise of agribusiness fostered the region’s integration into the state and nation, encouraging European American migrants and Mexican immigrants to move there. This affected racial arrangements, class composition and formation, and La Raza’s identity formation. Out of this cauldron of social and economic ferment emerged a Mexican American civil rights movement.

This chapter addresses the social, demographic, and economic development of South Texas and the status of the Mexican-origin community. Urban San Antonio, semi-urban Corpus Christi, rural Alice, and the Lower Rio Grande Valley (the Valley), an agricultural region, are discussed. It also addresses the rise of the Mexican American middle class and the formation of the “Mexican race” in the context of heightened racial violence and segregation in the 1910s and 1920s.

Texas map (lower left) and detail showing South Texas–Mexico border region. Courtesy Molly O’Halloran Inc.

South Texas encompasses the state south of San Antonio, north of the Rio Grande, and east of the Gulf of Mexico.1 Today it includes the cities San Antonio, Corpus Christi, Laredo; towns like Alice; and the Rio Grande Valley. A homeland to indigenous peoples, Spain colonized this far northern frontier of its vast conquered territories in the Americas. Here, Spaniards, Indians, and racially mixed people established missions, pueblos and villas (towns), ranchos (ranches), and presidios (forts). San Antonio, Nuevo Santander, and Laredo became key settlements in the 1700s, and Spanish land grants permitted landownership with ranching and farming along the Rio Grande and Nueces River.2

Mexico inherited this region after it won its independence in 1821. After Texas independence, the Texas republic claimed the area, including the region south of the Nueces River, but was not able to attract European American settlement until after the Civil War. After the U.S.-Mexico War of 1846–1848, most South Texas residents continued to see Mexico as their homeland. Others connected to U.S. politics and participated in the Civil War. Around 1850, approximately 18,000 persons of Mexican origin, 2,500 European Americans, and several thousand Indians lived here.3 In the post–Civil War era, urban centers included San Antonio, Brownsville, Rio Grande City, El Paso, and Laredo, but few European Americans lived there.4 The railroad ran through San Antonio, Alice, Eagle Pass, and Laredo in the 1870s, spurring European American control of South Texas’ economic development.5

South Texas residents developed a distinctive border culture based on ranching and farming, the patriarchal family, the close-knit community, and proximity to Mexico.6 Despite an incipient hybrid American and Mexican culture, most continued to identify themselves as “Mexicans,” “México Texanos,” and members of “La Raza.”7 Although most were citizens of the United States since 1845 or 1848, few referred to themselves as “Mexican Americans” or “American citizens” in English or Spanish. Few took pride in an “American” identity. English was mostly foreign and unspoken. For this reason, scholars have called the region part of México de afuera, or “Greater Mexico.” South Texas was a México Texano homeland.8

CORPUS CHRISTI

Karankawas, Lipan Apaches, and other Indians first settled this region. Spanish and Mexican ranchers and farmers settled the Corpus Christi region in the 1760s. About seven hundred people lived there in the 1840s, and after the Civil War, it became a distribution center for South Texas and northern Mexico. The railroad arrived around 1880, leading to a population of more than ten thousand by 1910.9

The few Spanish land-grant owners here had lost their lands by the 1880s. The landless turned to tenancy and farm labor.10 Nueces County produced more cotton than any other in the United States; 60 percent of the production was owned by European American absentee growers.11 After 1910, a small number of Mexican-origin people became property owners. In 1914 only one person of Mexican descent in Nueces County owned land, but 585 did by 1929.12

Most of La Raza owned no property and worked as cotton pickers and were locked out of the higher-paying jobs in foundries, machine shops, creameries, cotton oil mills, and small factories. By 1932, 97 percent of the cotton pickers were of Mexican origin, having displaced African Americans by the mid-1920s.13 Scholar Dellos Urban Buckner reported that “large numbers” of La Raza left the Valley for the Corpus Christi area, where working conditions were better.14 Sixty-five percent of the county’s migrants came from the Valley in 1929.15

In the midst of this agricultural boom, Corpus Christi urbanized. In 1920 European Americans outnumbered La Raza two to one, but by 1930 La Raza outnumbered whites. Nearby Kingsville experienced similar demographic change; its Raza population more than doubled from 1920 to 1930.16 This mixed population prompted Paul S. Taylor to call Nueces County “an American Mexican frontier.”17

SAN ANTONIO

After World War I, San Antonio also experienced urbanization and demographic change. New railroads, highways, and air routes tied the city to the nation, and during World War I the military infrastructure expanded. The petrochemical, communications, and transportation industries grew, reducing the significance of agriculture, manufacturing, and the military. The city served as a labor distribution point for La Raza, with Mexican laborers en route to Midwestern steel mills and Eastern coal mines.18 Better transportation and communication facilitated the city’s urbanization. Five railroads connected to San Antonio, and the Texas Highway Department opened in 1917. By 1924, nineteen hard-surfaced roads left San Antonio.19

The city’s population grew from 53,321 in 1900 to 231,542 in 1930, making it the most populous Texas city for several years in the 1920s. It had the most Mexican-origin people in the nation from 1890 to 1900. In 1910 they numbered 29,480 and in 1930 82,373 (35 percent of the city’s total population).20

LOWER RIO GRANDE VALLEY

South of Corpus Christi lies the Valley, an agricultural heartland spanning a million acres. The Valley remained largely untouched by land development, commercial agriculture, railroads, and European American contact until 1904, when the railroad arrived.21 As agribusiness grew in the 1920s, the population increased, new towns arose, and class structure changed. The Valley was becoming the state’s most productive agricultural region.22 Mexican-origin men prepared the land for agribusiness and picked the crops.

Commenting on changing racial and class arrangements, historian Jovita González called the arrival of European Americans an “American invasion.”23 She noted,

For nearly two hundred years the Texas-Mexicans had lived knowing very little and caring less of what was going on in the United States. . . . These people had lived so long in their communities that it was home to them, and home to them meant Mexico. . . . Mexican newspapers brought them news of the outside, their children were educated in Mexican schools, Spanish was the language of the people. Mexican currency was used altogether.24

She also called the arrival of “Americans” (whites) “a material as well as a spiritual blow to the Mexicans, particularly to the landed aristocracy.”25 She elaborated on the “Mexicanness” of the region rather than its “Americanness,” noting that few schoolchildren spoke English.

New towns sprang up. By 1929 these included Harlingen (population 14,000), San Benito (12,500), McAllen (10,000), Edinburg (7,000), Mission (6,500), Mercedes (7,000), Weslaco (7,000), and Donna (6,000). Brownsville’s population grew to 22,000. By 1929, three-fourths of the Valley’s residents lived in towns of populations over 2,500.26 Race relations also changed.

European Americans, many Midwesterners, now dominated Hidalgo and Cameron Counties in the Valley and nearby Zapata, Webb, and Duval Counties. Hidalgo, once 98 percent Raza, was now 54 percent Raza; Cameron’s Raza populace fell from 88 percent to 50 percent.27 Raza farmworkers, immigrant and native, were at the bottom of this new class order. A small México Texano middle class was emerging, and a few European American businessmen were getting rich.

ALICE

Fifty-four miles west of Corpus Christi lies the small town of Alice. It became the state’s busiest cattle-shipping center after the railroad arrived in 1883. Incorporating in 1904 with a population of 887 people, it became the seat of the new county—Jim Wells—in 1911. The 1920 population was 1,180, but a minor oil boom spurred the population to 4,239 by 1931, leading the town to call itself the “Hub City of South Texas.”28

Alice had a significant Mexican population. Spanish-language newspapers appeared, including El Eco in 1896, El Cosmopolita in 1903, and El Latino Americano in 1920, suggesting a literate middle-class Spanish-speaking audience. Still, Alice, like Valley towns farther south, was a “dual town,” racially segregated with “Mexicans” on one side of town and Euro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One Society and Ideology

- Part Two Politics

- Part Three Theory and Methodology

- Conclusion

- Appendices

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index