![]()

PART I

BACKGROUND AND THEORY

![]()

CHAPTER 1

After Legalization

The Persistent Violation of International Human Rights Norms

After Romania and Bulgaria joined the European Union (EU) in 2007, about 15,000–20,000 Roma individuals from these states went to France in search of a better life.1 As citizens of the EU, the Roma, also known more pejoratively as Gypsies, were entitled to travel to and reside freely in other member states subject to a few conditions.2 The arrival of these generally poor and highly visible immigrants elicited strong domestic opposition.3 One poll found that 77 percent of French people agreed with then interior minister Manuel Valls that the Roma do not integrate in French society and belong in their countries of origin.4 In July 2013 Jean-Marie Le Pen, the former leader of the National Front party, described the Roma as “irritant and smelly,” while Gilles Bourdouleix, a member of the French National Assembly, said about the Roma: “Maybe Hitler did not kill enough.”5

The French government came under pressure to return Roma immigrants to their countries of origin. But simply expelling them as a group would have incurred significant legal costs. EU legislation and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) prohibit collective expulsions based on race and ethnicity.6 Such blatantly discriminatory expulsions of the Roma would have invited adverse rulings by domestic courts, the European Court of Justice (ECJ), and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). French officials devised a clever solution to satisfy domestic constituents without having to pay the costs of violating the law. Under the “humanitarian return assistance” policy (aide au retour humanitaire), they offered thousands of Roma nominal amounts of money to leave France “voluntarily.”7 Departures occurred in the shadow of police intimidation, the confiscation of identity documents, and deep Roma poverty, all of which undermined the voluntariness of these returns. According to one Roma, “The police told us to choose: either we willingly left now, or we would be forcibly removed later.”8

“Humanitarian returns” were widely seen as normatively inappropriate because they violated the international norm of racial equality, the social standard for appropriate nondiscriminatory behavior. Human rights experts and activists emphasized that the policy, which singled out the Roma for returns and did not give them a genuine choice to stay, violated their right to racial equality regarding free movement and residence.9 One legal scholar affirmed: “Regardless of its legality, the repatriation program feels intuitively wrong, and sends a strong message of ‘we don’t want you here’ to the Roma people.”10 Nearly half of the French officials I interviewed privately agreed. A French group of NGOs, Collectif National Droit de l’Homme Romeurope, concluded: “The conditions of implementation and the perverse effects of this device absolutely deny its qualification as ‘humanitarian.’”11

Despite its inappropriateness, this strategy has provided France sufficient legal cover to satisfy domestic constituents and remove unwanted Roma immigrants with legal impunity. French prime minister François Fillon stated: “The recent deportations of Roma to their countries of origin made by our country have been made in full compliance with European law.”12 Many courts understand expulsion based on a relatively narrow meaning of compulsion. Subtle forms of intimidation and compulsion did not show up on their narrow legal radars, even when they violated the relevant international social norms. France could claim that humanitarian returns did not involve compulsion and were voluntary. They did not technically qualify as expulsion and were therefore legal. There have been no court rulings, domestic or European, against “humanitarian returns.”

This example illustrates states’ ability to resist unwanted human rights obligations by violating international human rights norms in the shadow of technical legality. It also raises broader questions about the limits of legalization for protecting human rights norms. Since World War II human rights norms have undergone extensive legalization or codification into international treaty law.13 The standard expectation is that legalization strengthens human rights norms and increases norm following by making these norms more enforceable, legitimate, and politically salient.14 Despite these potential benefits, the violation of human rights norms often persists and sometimes even increases after legalization.15 It is suggestive that the strongest regional human rights regime, that of Europe, struggles when it comes to protecting the human rights of the Roma.16 A 2017 survey by the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency lamented that despite strengthening EU antidiscrimination legislation, there has been “little progress” in countering discrimination on the ground.17 In 2018 the same agency concluded: “The existing evidence of wide-spread discrimination against Roma suggests that the Race Equality Directive (2000/43/EU) is not effective—at least with respect to that particular group. Critical assessment by both the EU and the Member States is needed of why this is the case and what measures are required to remedy the existing situation.”18

How do states violate human rights norms after legalization? Why are these violations so persistent? What are the limits of legalization for protecting human rights norms? Existing studies in international relations offer a variety of answers to these questions, but most focus on state actions that violate both human rights norms and the laws designed to protect them. This focus is valuable, but it does not capture cases like France’s humanitarian returns, where states violate human rights norms without technically violating the law. Because existing studies conflate laws and norms, they do not distinguish between norm violations and law violations. Yet norm breakers are not necessarily lawbreakers. Focusing on norm violations that are illegal obscures the possibility that agents could violate norms in a legal manner, engaging in actions that are awful but lawful.

This book argues that the violation of human rights norms continues after legalization under the cover of technical legality. Its starting point is that human rights are embedded in and guide action through both laws and norms.19 The next chapter defines and distinguishes norms and laws. Suffice it to say here that laws are formal rules that score higher on precision, obligation, and delegation, while norms are informal rules of appropriate behavior that score lower on these dimensions.20 Although laws and norms interact and overlap considerably, they mirror each other selectively, engendering norm-law gaps. Because of these gaps, law compliance and legality on the one hand and norm following and normative appropriateness on the other often diverge. Most relevant for our discussion, actions that are technically legal may be normatively inappropriate.

The book provides a two-part theory of norm evasion. The first part focuses on norm evasion as a strategy and explains why and how states engage in it. Different domestic and international groups compete to shape state policy. In this stylized account, one side favors policies that comply with human rights laws and norms, whereas the other favors policies that violate human rights laws and norms. When the two groups are similar in strength, obeying both laws and norms or transgressing both can be very costly. Instead, the more attractive options are mixed strategies: follow norms but violate laws or comply with laws but violate norms. When officials deem law violations costlier than norm violations, the state will exploit norm-law gaps to violate norms in a technically legal fashion. This strategy, which I label norm evasion, allows the state to satisfy groups opposed to human rights while lowering the legal costs of doing so. The second part of the theory focuses on norm evasion as an outcome of a complex interactive process between the state and other relevant agents. After the state chooses an action, human rights supporters will contest its legality in court and its appropriateness in public and private discourse. The state and human rights opponents will defend its legality and appropriateness. The less often that courts rule against the state’s action and the more discourses characterize this action as inappropriate, the more it becomes constructed as norm evasion. Another way to put this is that when the state wins the competition over the legality of its actions and loses that over appropriateness, its actions are constructed as norm evasion.

I illustrate the argument in original and rich case studies of the French expulsion of Roma immigrants (2007–17) and the Czech segregation of Roma children in schools for those with mild mental disabilities (1993–2017). As I discuss later in detail, I find that for much of the period under study France and the Czech Republic have engaged in norm evasion. Their treatment of the Roma has violated the international norm of racial equality in a technically legal fashion.

The book sheds unique light on international politics at the intersection of laws and norms. It has a number of specific implications for the study and practice of international politics and human rights: it cautions that the good news about law compliance is not necessarily good news about norm following; it draws attention to subtle legal practices through which democracies can undermine human rights generally and racial equality specifically; and it provides policy-relevant knowledge for human rights advocacy.

Having summarized the argument, it is also important to clarify what I do not argue. While norm evasion reveals the limits of the law’s ability to protect human rights, it does not deny that the law also offers possibilities in this respect. After all, norm violations may be worse in the absence of legalization. From this perspective the argument can be located between those championing and criticizing human rights law, though closer to the latter.21 I do not argue that in the absence of legalization human rights practices would necessarily be better. Even when they are not legalized, human rights and the associated social norms are limited in their ability to improve people’s lives. Others have amply documented these limits.22 I seek to address the limits of legalization that stem not so much from the limits of the underlying norms and rights but from the drafting, interpretation, implementation, and enforcement of the law.23 The result, I hope, is a theoretically interesting and empirically nuanced argument that takes us a step closer to addressing what Posner considers the key challenge for scholars: “explaining when international law works and what its limits are.”24

The remainder of the chapter unfolds as follows. In the next two sections I review and critique the international relations literature for overlooking norm evasion and propose a new typology that captures it. I then summarize the theory and its main contributions. Following that, I place the book in the broader interdisciplinary literature on rules, race, and rights. The last two sections introduce the Roma and outline the road map of the book.

A New Typology of Norm Following and Law Compliance

Existing studies in international relations contend that if human rights abuses persist after legalization it is because agents commit to but do not comply with human rights laws and norms.25 In some cases, captured by the “managerial” approach, noncompliance is unintentional. States commit with the intention of complying with the law, but capacity problems, legal ambiguity and indeterminacy, and unanticipated changes over time prevent them from doing so.26 In other cases, captured by the “enforcement” approach, states engage in noncompliance intentionally. This is especially likely because standard enforcement mechanisms of international law that involve reciprocity, reputation, and retaliation are weaker in the area of human rights.27

Indeed, after legalization many violations of human rights norms take the form of law violation. However, this conventional wisdom implicitly assumes that international (human rights) laws and international (human rights) norms are essentially the same.28 It then conflates law violation with norm violation and law compliance with norm following. Although there is considerable overlap between human rights norms and laws, they are not necessarily identical. Just as human rights cannot be reduced to legal rights, human rights norms cannot be reduced to human rights laws.29 For this reason, law noncompliance and norm violation on the one hand and legality and appropriateness on the other can diverge: “But no matter where the lines are drawn, the unavoidable incompleteness of rules will mean that in some circumstances, appropriate actions (i.e. those that are not socially undesirable, excepting their illegality) will fall on the ‘illegal’ side of the line, and inappropriate actions will fall on the ‘legal’ side.”30 Focusing only on norm violations that also violate the law and are illegal truncates our understanding of resistance to human rights perhaps as much as focusing on revolutions truncates our understanding of how the weak resist the domination of the strong.31 We would miss everyday forms of legal resistance to human rights norms that are subtle but consequential.

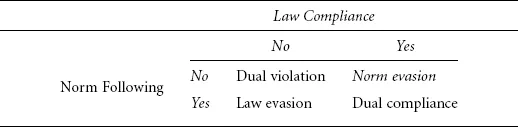

Table 1. A Typology of Norm Following and Law Compliance

To capture this subtle form of action we need to distinguish between law compliance and norm following. As a first step in this direction, I propose a novel typology that distinguishes between law compliance and violation on the one hand and norm following and violation on the other (Table 1). Based on these distinctions, I identify four types of actions. First, what I call dual compliance involves obeying both norms and laws. It is similar to “fulfillment,” which for Brysk and Jimenez is necessary to get from legal rights to justice.32 Second, what I call law evasion entails law violation and norm following.33 Other scholars capture similar phenomena through labels like “operational noncompliance,” “constructive noncompliance,” and the “moral right to do legal wrong.”34 Examples include the “illegal but legitimate” Kosovo intervention in 1999 and some forms of conscientious objection and civil disobedience.35 While important in their own right, dual compliance and law evasion have little to say about human rights norm violations after legalization, since they both involve norm following.

The next two forms of action are more relevant for the purposes of this book. What I label dual violation consists of transgressing both laws and norms. This is the emphasis of existing studies discussed at the beginning ...