Importance of Natural Hazard Mitigation

Disasters happen when nature’s extreme forces strike exposed people and property. These recurring natural phenomena, such as floods, hurricanes, and earthquakes, are known as natural hazard events. When natural hazard events take place in unpopulated areas, no disaster occurs, when they take place in developed areas, damaging life and property, they are called natural disasters. The magnitude of a disaster depends on the intensity of the natural hazard event, the number of people and structures exposed to it, and the effectiveness of pre-event mitigation actions in protecting people and property from hazard forces.

Natural disasters have grown larger as more people and property have become exposed to natural hazards. Unfortunately, the places where hazards occur are often the same places where people want to live—along ocean shores and riverfronts or near earthquake faults. As more urban development takes place in such high-hazard areas, the risk of damage and injury from disasters multiplies. During the first half of the 1990s, the United States suffered unparalleled damage from natural disasters. Hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, and other natural disasters caused billions of dollars in damage, destroyed homes and businesses, and cut off roads, bridges, water systems, and other public infrastructure.

Yet much of the damage and suffering from natural disasters can be prevented. Natural hazard events cannot be prevented from occurring, but their impacts on people and property can be reduced if advance action is taken to mitigate risks and minimize vulnerability to natural disasters. Following disasters in the early 1990s, the U.S. Congress directed the Federal Emergency Management Agency to place its highest priority on natural hazard mitigation, shifting its emphasis from responding to, and recovering from, disasters once they have occurred to mitigating future hazard events. This marked a fundamental change, moving from reactive to proactive national emergency management policy.

This book describes and analyzes the way hazard mitigation has been carried out in the United States under the national disaster law—the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, enacted in 1988. We seek to answer questions about how the requirements of this law, establishing a national system for hazard mitigation, have worked in practice and how they might be made to work better. Our goal is a sound system of natural hazard mitigation, which we believe is a prerequisite to a safe future for the nation and its communities.

The Concept of Natural Hazard Mitigation

Natural hazard mitigation is advance action taken to reduce or eliminate the long-term risk to human life and property from natural hazards. Typically carried out as part of a coordinated mitigation strategy or plan, such actions, usually termed either structural or nonstructural, depending on whether they affect buildings or land use, include the following:

- Strengthening buildings and infrastructure exposed to hazards by means of building codes, engineering design, and construction practices to increase the resilience and damage resistance of the structures, as well as building protective structures such as dams, levees, and seawalls (structural mitigation)

- Avoiding hazard areas by directing new development away from known hazard locations through land use plans and regulations and by relocating damaged existing development to safe areas following a disaster (nonstructural mitigation)

- Maintaining protective features of the natural environment by protecting sand dunes, wetlands, forests and vegetated areas, and other ecological elements that absorb and reduce hazard impacts, helping to protect exposed buildings and people (nonstructural mitigation)

Of the four stages of disaster response—mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery—mitigation is the only one that takes place well before the disaster event. The other stages all occur just before or after the disaster. The preparedness stage includes short-term activities, such as evacuation and temporary property protection, undertaken when a disaster warning is received. The response stage includes short-term emergency aid and assistance, such as search-and-rescue operations and debris clearance, following the disaster. And the recovery stage includes postdisaster actions, such as rebuilding of damaged structures, to restore normal community operations (Godschalk, Brower, and Beatley 1989).

Natural hazard mitigation is an important national policy issue because monetary damages from natural disasters are reaching catastrophic proportions. Fueled by increasing urbanization in areas exposed to natural hazards, disaster costs have skyrocketed. Insurance companies can no longer continue insuring property in high-hazard areas. The federal Treasury is called on to pay huge sums for postdisaster relief, rebuilding, and recovery. And the personal monetary and psychic costs in lost homes and businesses and disrupted lives are staggering (see Box 1.1).

Disaster Costs

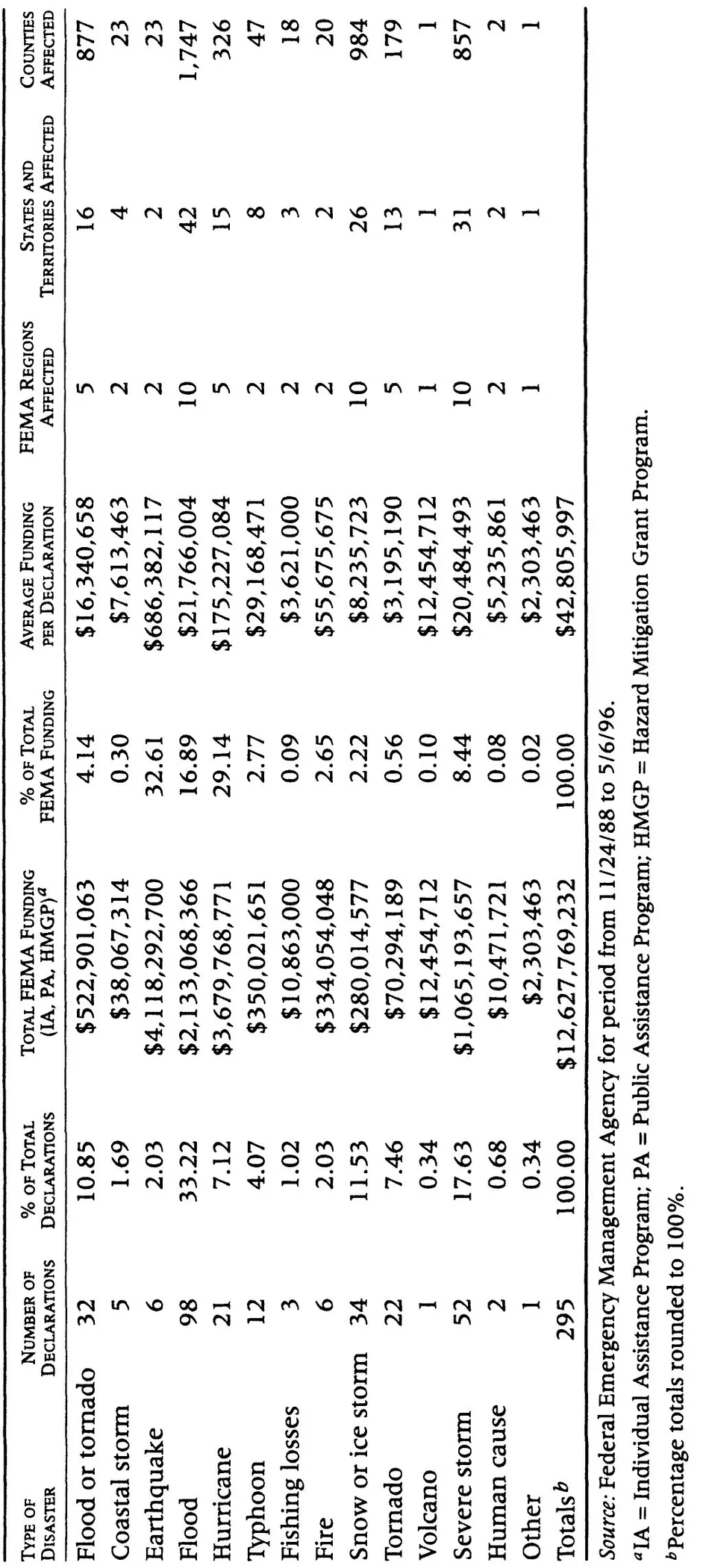

Disaster relief is a large and increasing public expenditure. Between the Stafford Act’s passage in 1988 and May 1996, a total of 295 disaster declarations have been made by the president, resulting in disaster relief expenditures of more than $12.6 billion by the Federal Emergency Management Agency for public and individual assistance and hazard mitigation grants. (Public assistance grants are made to state or local governments or nonprofit agencies for repair or restoration of disaster-damaged facilities.

Individual assistance grants are made to individuals or families to meet disaster-related expenses not otherwise covered. Hazard mitigation grants are made to state or local governments to reduce future hazard risks.) As shown in table 1.1, about 82 percent of this relief funding has gone to disasters involving hurricanes, typhoons, and coastal storms ($4.1 billion), flooding ($2.1 billion), and earthquakes ($4.1 billion).

Box 1.1. Record Natural Disasters of the 1990s

Hurricane Andrew

In 1992, Hurricane Andrew resulted in the highest total damage costs of any natural disaster in U.S. history, estimated at more than $25 billion.1 More than 36 million people live in the counties fronting the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, the area most susceptible to hurricanes and with the highest growth rates and rising property values (FEMA 1997). The next major hurricane there could be even more disastrous than Andrew, depending on where and when it strikes.

Midwest Floods

The costliest flood disaster in U.S. history was the 1993 flood in the upper Mississippi River basin, which affected nine midwestern states and resulted in an estimated $12-$16 billion in damage. In the United States, more than 9 million households and $390 billion in property are at risk from flooding. Property damage from flooding has averaged more than $2 billion per year in recent years (FEMA 1997).

Northridge Earthquake

The 1994 earthquake in Northridge, California, caused $20 billion in damage costs. Nationwide, more than 109 million people and 4.3 million businesses are exposed to some degree of seismic risk. The average annual loss from earthquakes is estimated at $1 billion (FEMA 1997a).

Disaster relief costs will certainly increase. Petak and Atkisson (1982) estimated that the real value of losses from nine common natural hazards in the United States will increase by a factor of 69 percent between 1980 and 2000. Between 1995 and 2010, costs of natural disasters are projected to be in the range of 5,000 lives and $90 billion (Engi 1995). Table 1.2 shows the total public and individual assistance and hazard mitigation grant funding for some recent large-scale disasters. Stafford Act expenditures for Hurricane Hugo were $1.27 billion, and expenditures for Hurricane Andrew were $1.64 billion. Expenditures for the 1994 Northridge earthquake alone were $3.32 billion, and expenditures for the 1993 Midwest floods approached $900 million. The geographic spread of these disasters is vast. The eleven disasters listed in table 1.2 affected some 822 counties in twenty-three states, with the Midwest floods alone hitting 430 counties.

Photo 1.1. Grand Forks, North Dakota, April 1997. Courtesy of the American Red Cross.

Table 1.1 . summary of Declared of Disasters, 1988-1996

Table 1.2. Selected Hurricanes, Floods, and Earthquakes, 1988–1996

Total insured losses caused by major natural disasters between 1989 and 1995 reached $45 billion (FEMA 1997a). Led by Hurricane Andrew’s insured losses of $15.5 billion in 1992 and the Northridge earthquake’s losses of $12.5 billion in 1994, these damages put serious strain on the nation’s private insurance system (See table 1.3). A number of small insurance companies went out of business, and several companies in particularly hazard-prone states discontinued hazard insurance.

Natural Hazard Mitigation Policy Framework

To counter the increasing damages from natural disasters, Congress created a mitigation policy framework consisting of a set of basic laws establishing goals, planning and implementation program tools to achieve the goals, and an intergovernmental system linking federal, state, and local government agencies responsible for operating the programs.

Table 1.3. Total Insured Losses from Major Natural Disasters, 1989-1995

| DISASTER | DATES | INSURED LOSSES (BILLIONS ) |

| Hurricane Andrew | 8/92 | $15.5 |

| Northridge earthquake | 1/94 | $12.5 |

| Hurricane Hugo | 9/89 | $4.2 |

| Hurricane Opal | 10/95 | $2.1 |

| Severe winter storms | 3/93 | $1.7 |

| Firestorm, Oakland, CA | 10/91 | $1.7 |

| Severe winter storms | 1/94–2/94 | $1.6 |

| Hurricane Iniki | 9/92 | $1.6 |

| Hailstorms, TX and NM | 5/95 | $1.135 |

| Loma Prieta earthquake | 10/89 | $0.96 |

| Fires, southern CA | 10/93–11/93 | $0.725 |

| Wind, hail, and tornadoes Denver, CO | 7/90 | $0.625 |

| Midwest floods | 6/93–8/93 | $0.6 |

| Total | 9/89–10/95 | $44.995 |

Source: FEMAa 1997a, p. xx.

Mitigation Policy Under the Stafford Act

In the United States, natural hazard mitigation policy is set forth in the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 U.S.C. 5121) and its accompanying regulations in Title 44 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 206 (44 C.F.R. 206). In the Stafford Act, Congress declares that because disasters cause loss of life, human suffering, loss of income, and property loss and damage; disrupt the normal functioning of governments and communities; and adversely affect individuals and families, special measures are necessary to assist states in rendering aid, assistance, emergency services, and reconstruction and rehabilitation of devastated areas. The intent of the act is to provide orderly and continuing federal assistance to state and local governments in carrying out their responsibilities to alleviate the suffering and damage caused by disasters. Among the means listed are comprehens...