![]()

Chapter 1

How Red Wagons Capture Students' Attention

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

All thinking begins with wonder.

—Socrates

As I sat in the amphitheater in one of the older buildings on the Harvard University campus, attending the first day of my summer physics class, my mind was miles away from the lecture scheduled to begin momentarily. This was Physics 101–102, an intensive six-week summer alternative to the usual full-year course.

The students did not know one another, but most were taking the class for the same reason: it was a prerequisite for medical school. I sat there dreading the upcoming hours of listening, reading, and solving seemingly irrelevant problems. My thoughts shifted from these scientific endeavors to exploring the city of Cambridge after class, the cute boy in front of me wearing the tie-dyed Grateful Dead shirt, and my pile of dirty laundry that would soon walk away on its own.

Suddenly, the swinging door leading to the lecture area burst open, and a man who appeared to be in his late 50s propelled himself into the room, crouched on a little red wagon. He wore a wizard's hat and was aiming an activated fire extinguisher at the wall. This was my introduction to Professor Baez, demonstrating Newton's third law of motion—that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.

It was a lesson I never forgot but sadly never emulated until 30 years later, when I left my neurology career and became a teacher, trying to capture the attention of my students. I recalled how powerfully that memorable lesson engaged my attention and wondered how teachers without red wagons and fire extinguishers could focus students' attention.

My subsequent investigations of the neuroscience research about attention led me to understand why that physics lesson worked. Further, it showed me that other uses of novelty and excitement through strategies of surprise, unexpected classroom events, dressing in costumes, playing music, showing dynamic videos, displaying comic strips or optical illusions on a screen, and even telling corny jokes could capture my students' attention and promote initial connections to the lesson. I learned that if I tapped into their natural curiosity and marshaled the power of predictions, I was more likely to sustain their attention throughout a lesson or unit. I also found that I could employ activities to develop students' executive functions of focused awareness and distraction inhibition. With these strategies in place, my students were better able to attend to and engage with lessons and more successfully engage in the process of constructing understanding and durable memories.

The Brain's Gatekeeper: The Reticular Activating System

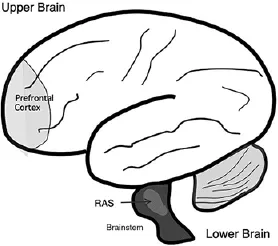

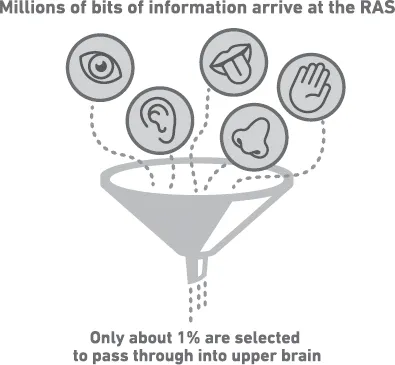

All learning begins with sensory information, but not all the sensory information available from the senses and environment is accepted for admission. For sensory input from what you hear, see, feel, smell, and taste to become memory, it must first be admitted by the brain's attention intake filter, the reticular activating system (RAS), shown in Figure 1.1 at the top of the brainstem (in the lower brain). This operation turns out to be very competitive. Every second, millions of bits of sensory information from the eyes, ears, nose, taste buds, internal organs, skin, muscles, and other sensors bombard the brain. Notably, though, only a tiny fraction—about 1 percent—of all that information passes up through the attention filter (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1. Reticular Activating System

Figure 1.2. From Input to Output: The Selective Filter of the RAS

The RAS is an attention-entry filter for incoming sensory information. It is key to arousing or "turning on" the brain's heightened level of receptivity to input. Soon you will learn how it is programmed in favor of letting in sensory information that's important for survival. Then we'll explore the development of more top-down attention focus management as children grow. Top-down management of attention focus refers to the ability to direct attention to a particular stimulus or event in the environment (Katsuki & Constantinidis, 2014). These management circuits increase one's ability to actively dictate some of the sensory information to be accepted by the RAS.

The Priorities of the First Gatekeeper

The work of the RAS follows the survival-oriented programming of other mammals living in unpredictable, often harsh environments. Because the capacity for intake is so limited, the selection process for what gets in must be rapid and efficient. To support survival success, it makes sense that priority intake scrutinizes for potential threat or for survival resources (e.g., food, shelter, mates). This scrutiny is reflected, then, in priority going to sensory information concerning what is changed, unexpected, or different in the environment (Brudzynski, 2014).

With its programming as an alerting filter, it is understandable how the RAS responds instinctually to what is new in the environment (Garcia-Rill, D'Onofrio, & Mahaffey, 2016). Living things need to respond to changes in their environment to survive. A rapid response to novelty optimizes the chance of survival. Mammals need shelter from sudden storms, access to new sources of water when streams dry up, and places to escape to when danger is imminent, so priority attention to the unexpected or unusual is helpful in revealing new available resources for these potential future needs (Awh, Belopolsky, & Theeuwes, 2012).

What RAS Programming Means for Students

The strong reaction to novelty makes sense for this more primitive system in the human brain, but it presents a challenge when teaching information that may not evoke interest or effort. If the RAS does not select the information delivered in a lesson, little will be "learned," so we'll be looking at how to incorporate RAS intake boosters into instruction. Before describing the relationship of the RAS intake to learning in students, let's briefly consider why we adults are not as prone to paying attention only to what glitters, sparkles, moves, or pops. Simply put, adults' neural networks related to top-down attention focus are more mature. These circuits, in our highest cognitive centers located in the brain's prefrontal cortex (see Figure 1.1), develop into more efficient circuits that allow us to send messages down to the RAS to influence what information it takes in.

The RAS response to the sensory information received affects the speed, content, and type of information that gains access into the higher-thinking regions in the prefrontal cortex. These top-down attention control circuits continue to develop through the twenties. Your interventions to strengthen these circuits can boost students' influence on what information passes through their RAS filter. Further, they can learn and incorporate strategies to block intake through the RAS of input that is irrelevant to the goal or task at hand (Petersen & Posner, 2012).

By neuroscience criteria, students' brains are always "paying attention." The RAS continually filters which sensory information gets in. Often, however, what gets in will not be the information you are providing in your instruction or through students' reading and homework. Students are frequently criticized for not paying attention, but we now know that failure to focus on classroom instruction does not mean their brains are inattentive. The RAS is paying attention to (letting in) sensory input, but unfortunately it may not be related to what is being taught at the time.

Because students' environments are full of new and enticing information from the visual, auditory, and kinesthetic inputs continually surrounding them (sometimes plugged into their ears from their devices), teachers are challenged to guide students to select and focus on the intended information. It takes guidance and effort to build their abilities to resist some of the distracting input competing for attention through their intake filter systems.

Opening Attention Intake

We all come across lessons or units that don't inherently capture our students' interest. Although you've no doubt developed effective strategies to jump-start students' attention, understanding how novelty, curiosity, surprise, the unexpected, and change can influence the RAS can expand your toolkit.

There are many creative ways to infuse your subject matter or lesson with a bit of novelty and curiosity. Despite the glitter of some of the examples that follow, we're not suggesting that "edu-tainment" with bells and whistles is the simple and sole answer to holding students' attention. These examples can be altered to fit a wide range of topics and subject areas. Some require advance preparation, whereas others rely on materials that you probably have on hand or involve a simple shift in your presentation style. Here are some favorites for captivating the RAS.

Show video clips available on the internet about the upcoming topic. In college, one of Malana's professors launched his social psychology classes with a relevant clip from the television show Seinfeld. The human foibles portrayed on the show were an engaging way to bring social psychology principles to life while capturing the attention of students in a large lecture hall.

Play music related to the coming lesson. For example, some jazz before a discussion of The Great Gatsby or the theme music from the game show Jeopardy! before reviewing for a test would engage learners and set the tone for the activity to come.

Move in a different way. For example, if you walk backward during your normal activities while students are entering the classroom, the novelty can spark their interest as you reveal the day's topic of instruction—negative numbers, going back in history, past tense, flashbacks in literature, "backward" analysis, or hindsight about events leading up to discoveries.

Speak in a different voice or vary your cadence or volume as you read aloud, describe a scientific phenomenon, or recount a historical event.

Use suspenseful pauses before saying something important, because silence is novel.

Wear a hat or even a costume relevant to the topic. Malana and her classmates looked forward to their AP biology class because their creative teacher would frequently dress and accessorize to fit the theme. Her skeleton earrings and T-shirt accompanied her anatomy lessons, and all manner of flora and fauna were represented to pair with her lectures on botany and zoology. Despite the challenging content, her playful nod to the theme of the day captured her students' notice and lightened the mood.

Make alterations in the classroom, such as a new display on a bulletin board. A vase of flowers on the front table could draw attention to an art lesson on Georgia O'Keefe, a language arts lesson focusing on sensory details, or a discussion of pesticides or the globalization of agriculture.

Greet students at the door with a topical riddle along with a hello. For example, the following classic riddle could be written on a large sheet of poster paper next to the door for students to read as they enter the classroom: "I have streets but not pavement; I have cities but no buildings; I have forests yet no trees; I have rivers yet no water. What am I?" As students come into the classroom, they will find the answer: maps! This novel introduction can lead to a lesson on cartography, the features of maps, different types of maps, what information is included and excluded from maps, and even the creation of student maps.

Hand students note cards with a math problem (review) before they enter the room. Explain that calculating the answer will provide them with the number of the table at which they will sit that day.

Start with an unusual fact or offer a provocative quote. Invite students to consider who might have said it and why, and how it might connect to the day's theme. For example, you could post the following quote for students to ponder, initially without an attribution, before a chemistry discussion on entropy, a lesson on seasonal changes in ecosystems, or an analysis of relationships in a novel: "Nothing is absolute. Everything changes, everything moves, everything revolves, everything flies and goes away." You could pose questions such as, Who might have said this? What might this person have been referring to? How could the quote relate to the topic we are going to discuss today? Following the lesson, you could return to the quote and ask some follow-up questions: In what ways is this quote similar to what we learned today? How does it differ? What else could it connect to in chemistry, ecology, literature, and so on? This quote was said by artist Frida Kahlo. How does that information affect your reflections?

Use color to highlight something novel. We know that colored flyers in students' Friday folders tend to get more attention. Color and unusual color changes, such as a picture of a red river or a purple polka-dotted tree, do the same in class openings.

If taking attendance, have students say a response word instead of the usual "present" or "here." Your prompt can be "What was the color of your first bicycle?" Not only will color activate attention, but classmates' curiosity about their friends' bicycles may reduce the class disruption that can occur during the boring process of taking roll.

Use extremes. For example, because mammals survive in unpredictable environments, it would be reasonable for priority sensory selection to alert them to things that are more extreme than the rest of the environment, such as a huge wolf or a swarm of bees. You could use extreme numbers to add a surprising or dramatic element to a math word problem related to teaching the metric system, such as "The 3-month-old girl threw the ball 3,000 meters farther than the pitching machine did. Calculate the distance in feet that she threw it." You could also use outrageous statistics to prompt discussions at the outset of a topic. Books such as Guinness World Records have many real-life examples of extremes.

Start your presentations with a joke. The following pun would be a playful intro to any number of science or math activities. Q: Why didn't the sun go to college? A: It already had 27 million degrees!

Dazzle with surprising visuals. Often when students came into my math class, I had optical illusions projected, provoking their interest and conveying the message that they should always look beyond the obvious.

Start a lesson by mentioning relevant community or school events of high interest that can tie back to the lecture topic of the day. For example, if the local city council voted to build a parking lot instead of a skateboard park on available land, students could debate the pros and cons of the decision and ...