![]()

Chapter 1

What will I do to establish and communicate learning goals, track student progress, and celebrate success?

Arguably the most basic issue a teacher can consider is what he or she will do to establish and communicate learning goals, track student progress, and celebrate success. In effect, this design question includes three distinct but highly related elements: (1) setting and communicating learning goals, (2) tracking student progress, and (3) celebrating success. These elements have a fairly straightforward relationship. Establishing and communicating learning goals are the starting place. After all, for learning to be effective, clear targets in terms of information and skill must be established. But establishing and communicating learning goals alone do not suffice to enhance student learning. Rather, once goals have been set it is natural and necessary to track progress. This assessment does not occur at the end of a unit only but throughout the unit. Finally, given that each student has made progress in one or more learning goals, the teacher and students can celebrate those successes.

In the Classroom

Let’s start by looking at a classroom scenario as an example. Mr. Hutchins begins his unit on Hiroshima and Nagasaki by passing out a sheet of paper with the three learning goals for the unit:

- Goal 1. Students will understand the major events leading up to the development of the atomic bomb, starting with Einstein’s publication of the theory of special relativity in 1905 and ending with the development of the two bombs Little Boy and Fat Man in 1945.

- Goal 2. Students will understand the major factors involved in making the decision to use atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

- Goal 3. Students will understand the effects that using atomic weapons had on the outcome of World War II and the Japanese people.

At the bottom of the page is a line on which students record their own goal for the unit. To facilitate this step, Mr. Hutchins has a brief whole-class discussion and asks students to identify aspects of the content about which they want to learn more. One student says: “By the end of the unit I want to know about the Japanese Samurai.” Mr. Hutchins explains that the Samurai were warriors centuries before World War II but that the Samurai spirit definitely was a part of the Japanese view of combat. He says that sounds like a great personal goal.

For each learning goal, Mr. Hutchins has created a rubric that spells out specific levels of understanding. He discusses each level with students and explains that these levels will become even more clear as the unit goes on. Throughout the unit, Mr. Hutchins assesses students’ progress on the learning goals using quizzes, tests, and even informal assessments such as brief discussions with students. Each assessment is scored using the rubric distributed on the first day.

As formative information is collected regarding student progress on these goals, students chart their progress using graphs. At first some students are dismayed by the fact that their initial scores are quite low—1s and 2s on the rubric. But throughout the unit students see their scores gradually rise. They soon realize that even if you begin the unit with a score of 0 for a particular learning goal, you can end up with a score of 4.

By the end of the unit virtually all students have demonstrated that they have learned, even though everyone does not end up with the same final score. Progress is celebrated for each student. For each learning goal, Mr. Hutchins recognizes those students who gained one point on the scale, each student who gained two points on the scale, and so on. Virtually every student in class has a sense of accomplishment by the unit’s end.

Research and Theory

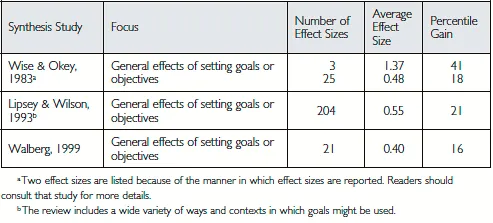

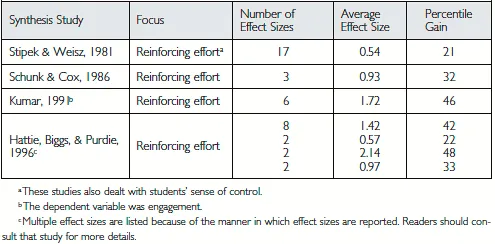

As demonstrated by the scenario for Mr. Hutchins’s class, this design question includes a number of components, one of which is goal setting. Figure 1.1 summarizes the findings from a number of synthesis studies on goal setting.

Figure 1.1. Research Results for Goal Setting

To interpret these findings, it is important to understand the concept of an effect size. Briefly, in this text an effect size tells you how much larger (or smaller) you might expect the average score to be in a class where students use a particular strategy as compared to a class where the strategy is not used. In Figure 1.1 three studies are reported, and effect sizes are reported for each. Each of these studies is a synthesis study, in that it summarizes the results from a number of other studies. For example, the Lipsey and Wilson (1993) study synthesizes findings from 204 reports. Consider the average effect size of 0.55 from those 204 effect sizes. This means that in the 204 studies they examined, the average score in classes where goal setting was effectively employed was 0.55 standard deviations greater than the average score in classes where goal setting was not employed. Perhaps the easiest way to interpret this effect size is to examine the last column of Figure 1.1, which reports percentile gains. For the Lipsey and Wilson effect size of 0.55, the percentile gain is 21. This means that the average score in classes where goal setting was effectively employed would be 21 percentile points higher than the average score in classes where goal setting was not employed. (For a more detailed discussion of effect sizes and their interpretations, see Marzano, Waters, & McNulty, 2005.)

One additional point should be made about the effect sizes reported in this text. They are averages. Of the 204 effect sizes, some are much larger than the 0.55 average, and some are much lower. In fact, some are below zero, which indicates that the classrooms where goals were not set outperformed the classrooms where goals were set. This is almost always the case with research regarding instructional strategies. Seeing effect sizes like those reported in Figure 1.1 tells us that goal setting has a general tendency to enhance learning. However, educators must remember that the goal-setting strategy and every other strategy mentioned in this book must be done well and at the right time to produce positive effects on student learning.

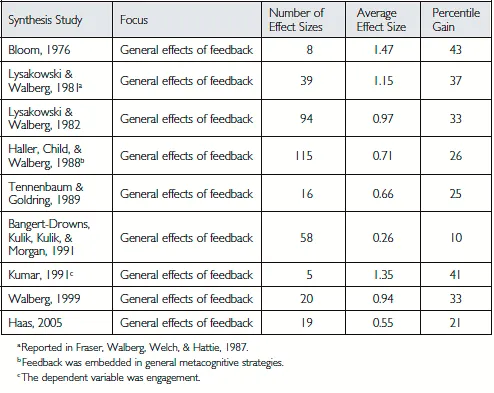

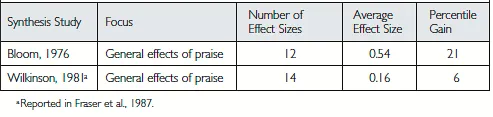

As illustrated in Mr. Hutchins’s scenario, feedback is intimately related to goal setting. Figure 1.2 reports the findings from synthesis studies on feedback.

Figure 1.2. Research Results for Feedback

Notice that the effect sizes in Figure 1.2 tend to be a bit larger than those reported in Figure 1.1. This makes intuitive sense. Goal setting is the beginning step only in this design question. Clear goals establish an initial target. Feedback provides students with information regarding their progress toward that target. Goal setting and feedback used in tandem are probably more powerful than either one in isolation. In fact, without clear goals it might be difficult to provide effective feedback.

Formative assessment is another line of research related to the research on feedback. Teachers administer formative assessments while students are learning new information or new skills. In contrast, teachers administer summative assessments at the end of learning experiences, for example, at the end of the semester or the school year. Major reviews of research on the effects of formative assessment indicate that it might be one of the more powerful weapons in a teacher’s arsenal. To illustrate, as a result of a synthesis of more than 250 studies, Black and Wiliam (1998) describe the impact of effective formative assessment in the following way:

The research reported here shows conclusively that formative assessment does improve learning. The gains in achievement appear to be quite considerable, and as noted earlier, amongst the largest ever reported for educational interventions. As an illustration of just how big these gains are, an effect size of 0.7, if it could be achieved on a nationwide scale, would be equivalent to raising the mathematics attainment score of an “average” country like England, New Zealand, or the United States into the “top five” after the Pacific rim countries of Singapore, Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong. (p. 61)

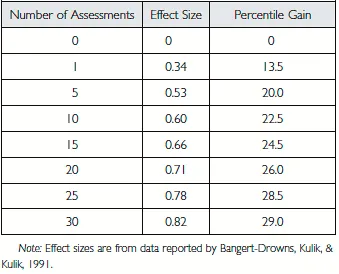

One strong finding from the research on formative assessment is that the frequency of assessments is related to student academic achievement. This is demonstrated in the meta-analysis by Bangert-Drowns, Kulik, and Kulik (1991). Figure 1.3 depicts their analysis of findings from 29 studies on the frequency of assessments.

Figure 1.3. Achieved Gain Associated with Number of Assessments over 15 Weeks

To interpret Figure 1.3, assume that we are examining the learning of a particular student who is involved in a 15-week course. (For a discussion of how this figure was constructed, see Marzano, 2006, Technical Note 2.2.) Figure 1.3 depicts the increase in learning one might expect when differing quantities of formative assessments are employed during that 15-week session. If five assessments are employed, a gain in student achievement of 20 percentile points is expected. If 25 assessments are administered, a gain in student achievement of 28.5 percentile points is expected, and so on. This same phenomenon is reported by Fuchs and Fuchs (1986) in their meta-analysis of 21 controlled studies. They report that providing two assessments per week results in an effect size of 0.85 or a percentile gain of 30 points.

A third critical component of this design question is the area of research on reinforcing effort and providing recognition for accomplishments. Reinforcing effort means that students see a direct link between how hard they try at a particular task and their success at that task. Over the years, research has provided evidence for this intuitively appealing notion, as summarized in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4. Research Results for Reinforcing Effort

Among other things, reinforcing effort means that students see a direct relationship between how hard they work and how much they learn. Quite obviously, formative assessments aid this dynamic in that students can observe the increase in their learning over time.

Providing recognition for student learning is a bit of a contentious issue—at least on the surface. Figure 1.5 reports the results of two synthesis studies on the effects of praise on student performance. The results reported by Wilkinson (1981) are not very compelling, in that praise does not seem to have much of an effect is student achievement. The 6 percentile point gain shown in those studies is not that large. On the other hand, the results reported by Bloom (1976) are noteworthy; a 21 percentile point gain is considerable. A plausible reason for the discrepancy is that these two studies were very general in nature, in that praise was defined in a wide variety of ways across studies.

Figure 1.5. Research Results on Praise

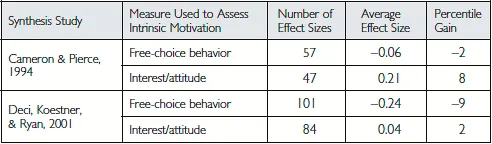

Other synthesis studies—particularly research on the effects of reward on intrinsic motivation—have been more focused in their analyses. Figure 1.6 summarizes findings from two major synthesis studies on the topic.

Figure 1.6. Research Results on Rewards

Among other things, both studies in Figure 1.6 examined the impact of what is commonly referred to as extrinsic rewards on what is referred to as intrinsic motivation. Both are somewhat fuzzy concepts that allow significant variation in how they are defined. (For a discussion, see Cameron & Pierce, 1994.) Considered at face value though, external reward is typically thought of as some type of token or payment for success. Intrinsic motivation is necessarily defined in contrast to extrinsic motivation. According to Cameron and Pierce (1994):

Intrinsically motivated behaviors are ones for which there is no apparent reward except the activity itself (Deci, 1971). Extrinsically motivated behaviors, on the other hand, refer to behaviors in which an external controlling variable [such as reward] can be readily identified. (p. 364)

The average effect sizes in Figure 1.6 show an uneven pattern—two effect sizes are below zero, and two effect sizes are above zero. However, the two effect sizes below zero are for studies that used free-choice behavior as the measure of intrinsic motivation. Typically these studies examine whether students (i.e., subjects) tend to engage in the task for which they are being rewarded even when they are not being asked to do the task. In both synthesis studies, the effect of extrinsic reward on free-choice behavior was negative. In contrast, positive effects (albeit small for the Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 2001, study) are reported when the measure of intrinsic motivation is students’ interest. Typically student interest is assessed by some form of self-report.

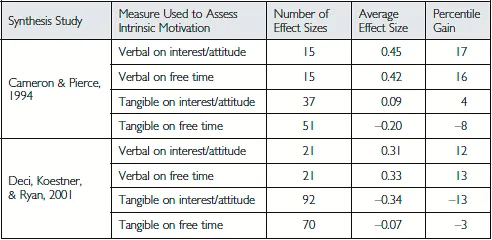

The contradictory findings for student interest versus student free-choice behavior do not provide any clear direction, but they do demonstrate the highly equivocal nature of the research on rewards and intrinsic motivation. A possible answer is found, however, by examining more carefully the distinction between free-time behavior and interest, as shown in Figure 1.7.

Figure 1.7. Influence of Abstract Versus Tangible Rewards

This research indicates that when verbal rewards are employed (e.g., positive comments about good performance, acknowledgments of knowledge gain) the trend is positive when intrinsic motivation is measured either by interest/attitude or by free-choice behavior. Even these results must be interpreted cautiously. Certainly, factors such as the age of students and the context in which rewards (verbal or otherwise) are given can influence their effect on s...