![]()

Chapter 1

Turning Any High-Poverty School into a High-Performing School

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

One of the biggest issues in improving schools is the perpetual search for the next bell and whistle. Educators who visit us and see our kids with both hands up—our way for students to communicate their ideas and responses to their teachers—want to grab onto things like that. The simple questions they should be focusing on are "What are you putting in front of your kids? Is it aligned to the highest level of rigor? Is it going to get the kids to the end in mind by the end of the school year?"

—Eric Sanchez, executive director, Henderson Collegiate PK–12 Schools, Henderson, NC

What Will It Take?

Most students who drop out—more than 1 million a year in the United States—leave school between the ages of 14 and 16 after enduring years of schooling in which frustration, embarrassment, failure, and minimal achievement were daily realities. Many simply lose hope, seeing little reason to stay in school. Of the roughly 84 percent who do make it to graduation, only slightly more than one-third of that group (41 percent) graduate prepared for the demands of the workplace or higher education. Overall graduation rates are even more dismal for Hispanic (76 percent), African American (79 percent), and Native American (72 percent) students. These rates reflect the failure of public schooling to work for a significant number of our children, our most precious resource (Stark & Noel, 2015).

Dwarfing the number of students who leave early is the number of kids who remain in school and graduate woefully underprepared for postsecondary education or the workplace. More than 3 million U.S. students enrolled in grades 9–12 in 2018 will not graduate on time with their classes (Stark & Noel, 2015). Combined, the number of students who drop out and the number who are unprepared for life beyond graduation illustrate the crisis that continues to plague the United States.

Not all students who drop out or who underachieve live in poverty, but many do. Despite recent modest progress in student achievement at the elementary and middle school levels, most of our high schools continue to demonstrate little success in closing long-standing achievement gaps between low-income and more advantaged students.

Why do so many people continue to be ambivalent about recognizing, let alone addressing, the continued reality of significant achievement disparity in our public schools? Are the daily needs of children who live in poverty and who are not reaching their potential too immense for most of us to grasp? Are their lives too distant from our own for us to see? Are we too embedded in an unspoken reality of classism and racism, as many argue? What will it take to educate the whole child if that child lives in poverty?

Questions to Ask—And Answer

Our children are the victims of this legacy. They suffer the consequences of a widespread unwillingness on the part of policymakers and education leaders to address three key questions:

- Why are some high-poverty schools high performing and others are not?

- What do we need to do to significantly improve our lowest-performing schools?

- What can we learn from high-performing, high-poverty schools that can help students who live in poverty achieve at higher levels, regardless of where they go to school?

Asking and answering these questions could result in improved educational outcomes for virtually every child living in poverty. Federal policy through the authorization of the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) continues to require states to identify and provide comprehensive services to their lowest-performing schools (the lowest-performing 5 percent of the state's Title I schools), as well as targeted services for low-performing subgroups of students in other schools. However, far too little has been done to create the conditions that research has demonstrated are necessary to ensure that most, if not all, low-performing schools and their students will significantly improve. In this second edition of Turning High-Poverty Schools into High-Performing Schoolss, we urge all educators and policymakers to study the successes of high-performing, high-poverty schools and to apply and act on this evidence in their own states, districts, and schools.

Leadership Is Essential

In 2007, Barr and Parrett were among the first to synthesize emerging research regarding how low-performing, high-poverty schools become high performing. They identified eight practices that significantly improved a low-performing, high-poverty school:

- Ensuring effective district and school leadership;

- Engaging parents, communities, and schools to work as partners;

- Understanding and holding high expectations for poor and culturally diverse students;

- Targeting low-performing students and schools, looking initially at reading skills;

- Aligning, monitoring, and managing the curriculum;

- Creating a culture of data and assessment literacy;

- Building and sustaining instructional capacity; and

- Reorganizing time, space, and transitions.

Barr and Parrett further concluded that the first practice mentioned—ensuring effective district and school leadership—linked to successful use of the other seven practices. In fact, 16 of the 18 studies that Barr and Parrett synthesized concluded that leadership, often collaborative and distributed, was essential to improve school practices or receive the district-level support necessary for high-poverty schools to become high performing.

A Framework for Action

Building on the contributions of Barr and Parrett (2007), the continuing work of the Education Trust, and that of other scholars and organizations, we initiated a study to develop a greater understanding of the impact and inner workings of leadership in HP/HP schools. This study resulted in the publication of the first edition of this book in 2012. Drawing from the research base, we developed a framework to capture conceptually the function of leadership in these schools, a Framework for Action. We then selected a small, diverse group of schools against which we could "test"—or, in research terms, member check—our framework. Each school selected demonstrated significant and sustained gains in academic achievement for at least three years; enrolled 40 percent or more students who qualified for free and reduced-price meals, using federal eligibility guidelines; reflected racial, ethnic, organizational, and geographic diversity; and were willing to work with us. In addition, the Education Trust, the U.S. Department of Education, and individual state departments of education had recognized these schools for their significant improvements in closing achievement gaps.

The leaders and educators we interviewed confirmed what the growing research base on HP/HP schools had identified and what was reflected in our framework: leadership—collaborative and distributed—served as the linchpin of success. This included the crucial role the principal and often a small group of teacher leaders and instructional coaches played in developing systemic, shared leadership capacity throughout the school, which was a catalyst for the creation of a healthy, safe, and supportive learning environment and an intentional focus on improving learning. Their actions in each of these areas also led to changes in the school's culture. The leaders and educators further noted that beyond influencing the classroom and the school at large, they developed relationships and formed partnerships with the district office, students' families, and the broader neighborhood and community to reach their goals.

The Framework Updated: The Framework for Collective Action

Following publication of the first edition of this book, we continued to visit and study HP/HP schools across the United States, as well as schools in Canada, the United Kingdom, Japan, South Africa, and Belize. We also had the opportunity to work with ASCD to study and video-document the factors that led to success in four HP/HP schools in three states. This research afforded us multiple opportunities to not only learn from these schools, but also validate or disconfirm elements of the framework. In this edition, we have revised the title of our framework to clearly assert the need and importance for school leaders, teachers, and all other educators and staff to work together; hence, the addition of the word collective to the title of the framework.

Our more recent study, which resulted in the publication of Disrupting Poverty: Five Powerful Classroom Practices (Budge & Parrett, 2018), sheds light on how teachers create classroom conditions to disrupt poverty's adverse influence on their students' learning. Our interviews of more than 40 effective classroom practitioners, over half of whom grew up in poverty, extended what we had learned in the original study.

Across states, nations, and cultures, we have found the primary tenets of the Framework for Collective Action to be consistent with factors that drive the transformation of low-performing, high-poverty schools to high performance. Moreover, we spent considerable time since the publication of the first edition in working with, supporting, and learning from many schools and districts in their quest to improve. These opportunities have also informed our research.

Based on this work and on our most current study of an additional 12 HP/HP schools, we have modified the Framework for Collective Action to acknowledge that the ubiquitous presence of a relentless sense of urgency to better serve all students is part of the cultural fabric of HP/HP schools. We have also acknowledged the importance of building collective efficacy—that is, a staff's shared belief that through their collective action they can positively influence student outcomes.

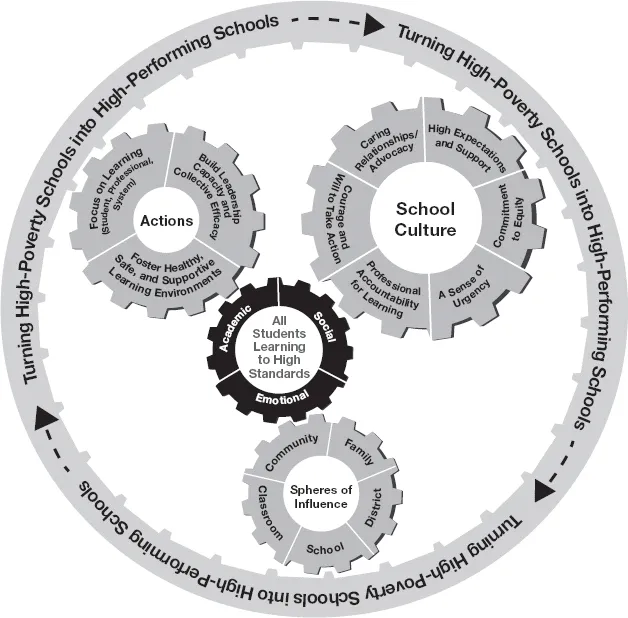

In the Framework for Collective Action (Figure 1.1), we illustrate the complex interactions among the three arenas in which educators work to support deeper levels of academic, social, and emotionoal learning by fashioning them as three gears: Actions, School Culture, and Spheres of Influence. These three gears connect to a central drive gear, All Students Learning to High Standards, which represents the core mission of high-performing, high-poverty schools. The inclusion of two new factors in the framework—a sense of urgency and collective efficacy—are elaborated in Chapter 4, as is the new placement of the drive gear.

Figure 1.1. A Framework for Collective Action: Leading High-Poverty Schools to High Performance

Disrupting the Cycle of Poverty

An effective school can rescue a child from a future of illiteracy, save hundreds of students from the grim reality awaiting those who exit school unprepared, and directly affect and improve our society. To do so, however, it must have leaders and educators who are oriented toward social justice. They ask questions that cause themselves and others to assess and critique the current conditions in their schools. They identify whose interests are being served by the current conditions—and whose are not. Their professional practice was consistent with what others have identified as social justice leadership (Dantley & Green, 2015; Dantley & Tillman, 2006; Scheurich & Skrla, 2003; Theoharis, 2009; Wang, 2018). Their vision for the school and their professional practice centered on students who, for whatever reason, were not succeeding and focused on inclusive practices ensuring that all students had equal opportunities for powerful instruction. They confronted structures, policies, practices, and mental maps that perpetuated inequities and thus created more equitable schools in which expectations were high, academic achievement as well as social and emotional learning improved overall, and achievement gaps were closing.

A Focus on Excellence, Equality, and Equity

The educators we interviewed and those in other HP/HP schools aim for three ideals: excellence, equality, and equity. What do we mean by this? First, these educators understand the distinction among the three words, as well as the possible tension among them. Excellence is the expectation in HP/HP schools—and it's not sacrificed to attain the other two goals of equality or equity. These schools are not places where curriculum is watered down, standards are lowered, or the pace of instruction is slowed to ensure equality in outcomes (e.g., where everyone gets an A). Rather, these schools strive for equality in outcomes (e.g., all students meet high standards or all students graduate ready for college) by committing to equitable opportunity for learning. In the case of students who live in poverty who are not learning to their potential, providing such opportunity often necessitates equitable, as opposed to equal, distribution of resources (time, money, people). In HP/HP schools, all students do not get the same thing—all students get what they need to succeed.

A Focus on Academic Achievement

Although many high-poverty schools are criticized for focusing too much on standardized testing, which has been perceived as narrowing the curriculum and emphasizing the "wrong" things, this was not the case in the schools we visited. They focused on multiple indicators of high performance, including (but not limited to) increased attendance, improved graduation rates, fewer discipline violations, increased parent and community involvement, improved pedagogy, and improved climate. All these factors contributed to or were indicators of improved academic learning and improved social and emotional learning.

At the end of the day, however, there can be no social justice without addressing academic achievement. These schools both increased academic achievement overall and closed achievement gaps, but as the framework in Figure 1.1 indicates, doing so involves more than simply focusing on raising standardized test scores. Our approach in writing this book is to clarify how schools can transform to better meet the needs of children and adolescents who live in poverty, as opposed to "fixing" these students so they better fit in the current system of schooling.

Place-Conscious Social Justice Leadership

Scholars (Rodriguez & Fabionar, 2010) who have studied the effect of poverty on students and schools assert, "When school leaders subscribe to conceptions of poverty that divorce individual instances from local and historical contexts, they risk employing prescriptive efforts that overlook individual and collective responses to poverty that can benefit learners" (p. 67). By contrast, when they understand the broader history of the community, school leaders and educators "are more likely to recognize community strategies that are used to cope with and counteract the conditions that maintain poverty" (p. 69).

Poverty looks different in every community. In a rural community where the formerly vibrant agriculture-based economy has struggled and the population is predominantly white, poverty will manifest itself in a specific way. It will look different in a suburban community that is, for the most part, working class but also serves as a refugee relocation site. And it will look different again in an urban setting with a racially diverse population and opportunities for employment that have been severely compromised for decades.

The educators in the HP/HP schools we studied were in tune with the neighborhoods and communities they served. Their leadership was informed by knowing the answers to questions such as these: What has happened in our community that has shaped collective experience? How have the demographics of the community changed over the ...