![]()

Chapter 1

Learning Targets: A Theory of Action

How to Catch a Monkey in the Wild: A Cautionary Tale

There are probably many ways to catch a monkey in the wild. One of the most effective is insidious in its simplicity.

The hunter gets a coconut and bores a small, cone-shaped hole in its shell, just large enough to allow a monkey to squeeze its paw inside. The hunter drains the coconut, ties it down, puts a piece of orange inside, and waits. Any monkey that comes by will smell the orange, put its paw inside the coconut to grab the juicy treat, and become trapped in the process. Capturing the monkey doesn't depend on the hunter's prowess, agility, or skill. Rather, it depends on the monkey's tenacious hold on the orange, a stubborn grip that renders it blind to a simple, lifesaving option: opening its paw.

Make no mistake: the hunter doesn't trap the monkey. The monkey's abiding tendency to stick firmly to its decision, ignore evidence to the contrary, and never question its actions is the trap that holds it captive.

The Beliefs That We Hold and the Beliefs That Hold Us

The beliefs that we hold also hold us. Our beliefs are the best predictors of our actions in any situation (Schreiber & Moss, 2002). And, like the monkey's death grip on the orange, our beliefs are deeply rooted, often invisible, and highly resistant to change. That's why so many "tried-but-not-true" methods remain alive and well in our classrooms despite clear evidence of their ineffectiveness. Take round-robin reading, for example. This practice has been rightly characterized as one of the most ineffectual practices still used in classrooms. You know the activity: the first student in a row reads the first paragraph from a book, the second student reads the second paragraph, and so on. Round-robin reading has long been declared a "disaster" in terms of listening and meaning-making (Sloan & Latham, 1981), and the reading comprehension it promotes pales in comparison to the effects of silent reading (Hoffman & Rasinski, 2003). So why do teachers still choose it for their students, and why do the principals who observe it in classrooms continue to turn a blind eye?

As our cautionary tale illustrates, it is essential for us to recognize our tendency to hold on to unexamined beliefs and practices. Each of us has our own mental map, a theory of action that directs our behavior in any situation (Argyris & Schön, 1974). What's tricky is that we actually operate under dual theories of action: an espoused theory and a theory in use. Our espoused theory is what we say we believe works in a given situation, whereas our theory in use is what actually guides our day-to-day actions (Argyris & Schön, 1974). For instance, if you ask a teacher what he believes makes assignments meaningful, he might tell you that students should be engaged in authentic tasks. Yet a visit to his classroom might reveal students copying vocabulary definitions from their textbooks. If you want to uncover what someone truly believes about any situation, look for what that person actually does in that situation.

Learning involves detecting and eliminating errors (Argyris & Schön, 1978). When something isn't working, our first reaction is to look for a new strategy—a way to fix the problem—that will allow us to hold on to our original beliefs, and to ignore any research or suggestions that go against our beliefs. Argyris and Schön (1974) call this belief-preserving line of reasoning single-loop learning.

Deeper levels of learning happen when we uncover what is not working and use that information to call our beliefs into question. When we question our beliefs and hold them up to critical scrutiny, we engage in the belief-altering process of double-loop learning (Argyris & Schön, 1974). Double-loop learning is how vibrant organizations change and grow (Argyris & Schön, 1978; Schön, 1983).

When Nobel laureate and astrophysicist Arno Penzias, honored for his discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation, was asked what accounted for his success, he replied, "I went for the jugular question …. Change starts with the individual. So the first thing I do each morning is ask myself, 'Why do I strongly believe what I believe?'"

The best way to eliminate the disparity between what we say and what we do and to invite the jugular questions is to forge a unified theory of action, shared across a school or district, that both explains and determines the actions that members take as individuals and as a community.

The Learning Target Theory of Action

In the introduction to this book, we included a "nutshell statement" of our theory of action: The most effective teaching and the most meaningful student learning happen when teachers design the right learning target for today's lesson and use it along with their students to aim for and assess understanding. Our theory grew from our continuing research with educators focused on raising student achievement through formative assessment processes (e.g., Brookhart, Moss, & Long, 2009, 2010, 2011; Moss & Brookhart, 2009; Moss, Brookhart, & Long, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c). What we discovered and continue to refine is an understanding of the central role that learning targets play in schools.

Learning targets are student-friendly descriptions—via words, pictures, actions, or some combination of the three—of what you intend students to learn or accomplish in a given lesson. When shared meaningfully, they become actual targets that students can see and direct their efforts toward. They also serve as targets for the adults in the school whose responsibility it is to plan, monitor, assess, and improve the quality of learning opportunities to raise the achievement of all students.

When educators share learning targets throughout today's lesson (a subject we discuss further in Chapter 3), they reframe what counts as evidence of expert teaching and meaningful learning. And they engage in double-loop learning to question the merits of their present beliefs and practices.

The Multiple Effects of a Learning Target Theory of Action

Effects on Teachers

Learning targets drive effective instructional decisions and high-quality teaching. Teaching expertise is not simply a matter of time spent in the classroom. In truth, the novice-versus-veteran debate presents a false dichotomy. Teachers of any age and at any stage of their careers can exhibit expertise. What expert teachers have in common is that they consistently make the on-the-spot decisions that advance student achievement (Hattie, 2002).

Designing and sharing specific learning targets to enhance student achievement in today's lesson requires and continually hones teachers' decision-making expertise. Teachers become better able to

- Plan and implement effective instruction;

- Describe exactly what students will learn, how well they will learn it, and what they will do to demonstrate that learning;

- Use their knowledge of typical and not-so-typical student progress to scaffold increased student understanding;

- Establish teacher look-fors to guide instructional decisions; and

- Translate success criteria into student look-fors that promote the development of assessment-capable students.

Guided by learning targets, teachers partner with their students during a formative learning cycle to gather and apply strong evidence of student learning to raise achievement (Moss & Brookhart, 2009). And they make informed decisions about how and when to differentiate instruction to challenge and engage all students in important and meaningful work.

Effects on Students

When students, guided by look-fors, aim for learning targets during today's lesson, they become engaged and empowered. They are better able to

- Compare where they are with where they need to go;

- Set specific goals for what they will accomplish;

- Choose effective strategies to achieve those goals; and

- Assess and adjust what they are doing to get there as they are doing it.

Students who take ownership of their learning attribute what they do well to decisions that they make and control. These factors not only increase students' ability to assess and regulate their own learning but also boost their motivation to learn as they progressively see themselves as more confident and competent learners.

Effects on Principals

When building principals look for what students are doing to hit learning targets during today's lesson, they improve their leadership practices. They become better able to

- Recognize what does and does not work to promote learning and achievement for all students and groups of students at the classroom level;

- Use up-to-the-minute student performance data to inform decision making; and

- Provide targeted feedback to individual teachers, groups of teachers, and building faculty as a whole.

Guided by learning targets, principals can promote coherence between actions at the classroom level and actions at the school level. They can also better allocate resources to promote student learning and lead professional development efforts in their building.

Effects on Central-Office Administrators

A learning target theory of action also enables central-office administrators to gather up-to-the-minute data about what is working in their classrooms and schools. They become better able to

- Identify key elements that support a districtwide strategy to raise student achievement;

- Communicate the relationship among these elements in an integrated and coherent way; and

- Use strong and cohesive performance data for decision making.

Guided by learning targets, central-office administrators can implement effective strategies to increase student achievement across buildings with different needs and unique characteristics shaped by the students, teachers, administrators, parents, and community members who work together in each building. They can develop and manage human capital to carry out their strategy for improvement, gain district coherence, and make the strategy scalable and sustainable.

Making each lesson meaningful and productive requires collective vigilance. It's not enough to "know" what works. Each day, students suffer the consequences of the mismatch between what we say is important and what actually happens during today's lesson.

The Nine Action Points

A learning target theory of action embodies the relationship among essential content, effective instruction, and meaningful learning. The nine action points that follow advance this theory of action and provide context for the ideas and suggestions in this book:

- Learning targets are the first principle of meaningful learning and effective teaching.

- Today's lesson should serve a purpose in a longer learning trajectory toward some larger learning goal.

- It's not a learning target unless both the teacher and the students aim for it during today's lesson.

- Every lesson needs a performance of understanding to make the learning target for today's lesson crystal clear.

- Expert teachers partner with their students during a formative learning cycle to make teaching and learning visible and to maximize opportunities to feed students forward.

- Setting and committing to specific, appropriate, and challenging goals lead to increased student achievement and motivation to learn.

- Intentionally developing assessment-capable students is a crucial step toward closing the achievement gap.

- What students are actually doing during today's lesson is both the source of and the yardstick for school improvement efforts.

- Improving the teaching-learning process requires everyone in the school—teachers, students, and administrators—to have specific learning targets and look-fors.

Action Point 1: Learning targets are the first principle of meaningful learning and effective teaching.

The purpose of effective instruction is to promote meaningful learning that raises student achievement. The quality of both teaching and learning is enhanced when teachers and students aim for and reach specific and challenging learning targets.

It's logical, really. To reach a destination, you need to know exactly where you are headed, plan the best route to get there, and monitor your progress along the way. When teachers take the time to plan lessons that focus on essential knowledge and skills and to engage students in critical reasoning processes to learn that content meaningfully, they enhance achievement for all students.

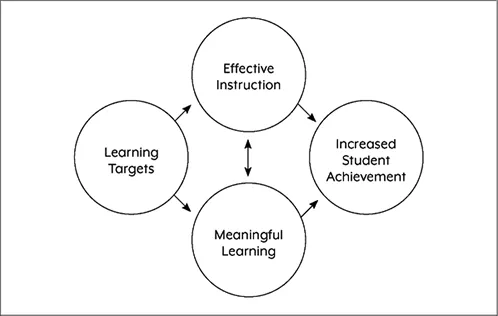

As Figure 1.1 illustrates, where you are headed in the lesson makes all the difference. Defining the lesson's intended destination in terms of a specific, challenging, and appropriate learning target informs both halves of the classroom learning team—teachers and students. Teachers and their students can codirect their energies as they aim for the shared target and track their performance to make adjustments as they go. Defining the right target is the first step and the driving force in this relationship.

Figure 1.1. The Role Learning Targets Play in Raising Student Achievement

Learning targets focus decisions about effective instruction and meaningful learning as well as their reciprocal relationship to raise student achievement.

A learning target guides everything the teacher does to set students up for success: selecting the essential content, skills, and reasoning processes to be learned; planning and delivering an effective lesson; sharing learning strategies; designing a strong performance of understanding; using effective teacher questioning; providing timely feedback to feed student learning forward; and assessing learning. The combined effect of these actions on student achievement depends on the target's clarity and degree of challenge.

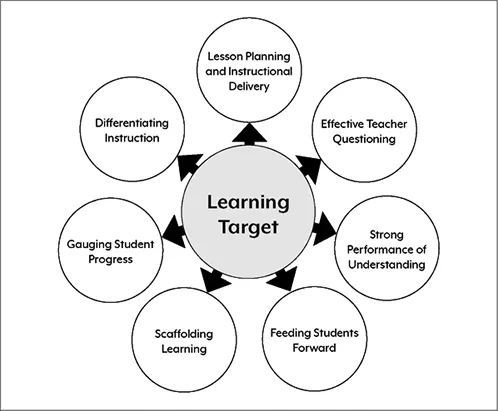

Figure 1.2 shows the elements of effective instruction that require and are strengthened by learning targets. The quality of these elements depends on defining a significant learning target.

Figure 1.2. The Central Role of Learning Targets in Effective Teaching

Identifying the right learning target for today's lesson leads to highly effective teaching decisions and classroom practices.

Larry, a high school social studies teacher, explained the effect of learning targets on his instructional decision making:

Taking the time to define the learning target for today's lesson brings laserlike precision to every decision I make. Once I know exactly where my students will be heading during the lesson, the learning target becomes the scalpel I use to trim and shape the lesson so that the essential content, skills, and reasoning processes take center stage. Now that I know what I want them to achieve, I can evaluate my instructional decisions as I go.

Similarly, meaningful student learning happens when students know their learning target, understand what quality work looks like, and engage in thought-provoking and challenging performances of understanding. These experiences help students deepen their understanding of important content, produce evidence of their learning, and learn to self-assess. When students self-assess, they internalize standards and assume greater responsibility for their own learning (Darling-Hammond et al., 2008). Figure 1.3 shows the elements of meaningful student learning that require and are strengthened by learning targets.

Figure 1.3. The Central Role of Learning Targets in Meaningful Student Lear...