In line with the description of ‘the new spirit of capitalism’ by Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello (2005), the dance artist performs immaterial labor on a flexible basis within the context of temporary projects, a situation that also demands persistent networking in order to ascertain future work opportunities. In 2002, dance scholar Mark Franko was probably one of the first to address the convergence between dance and work with the release of his book The Work of Dance: Labor, Movement and Identity in the 1930s (2002), which offers new tools for dance scholars to study the relation of politics to aesthetics. Following up on these two seminal works, I wanted to explore what is particular about contemporary dance artists today and their relation to work and how it ties in with more general issues of the project-based labor market and neoliberal society at large. I proceeded my research from the hypothesis that precarity is reflected in the work and lives of the artists as well as in the aesthetics and subject matter of their artistic work. Within this frame, I set out to examine the extent of precarity within the contemporary dance scenes of Brussels and Berlin, which both attract a high number of contemporary dance artists from around the globe. As I encountered a noticeable lack of research on the values, motivations, and tactics involved in contemporary dance artists’ trajectories, I desired to investigate the matter. For example, we do not know to what extent precarity is intertwined with motives, such as the wish to avoid working within hierarchically structured dance companies or to engage in projects that allow democratic forms of decision-making. Therefore, this study primarily questions if and in what ways the socio-economic position of contemporary dance artists affects the working process and the end product, and vice versa. In addition, I inquired into how the project-based work regime takes its toll on dance artists’ social and private life and their physical and mental state. Or in other words: to what extent is precarity in its plural forms (socio-economic, mental, physical, etc.) intertwined with working in art?

This book consists of three parts, preceded by two chapters that contextualize the research. The first chapter ‘Probing Precarity’ forms the starting point of my research. In this chapter, I introduce the discourse on precarity, the precariat, and precarious labor. In the second chapter, I outline my field of inquiry and present the methodology I have developed for this research. The methodology essentially combines methods from dance studies and the social sciences. The chapter provides an empirically grounded status quo of the socio-economic position of contemporary dance artists in Brussels and Berlin. In addition, I unravel the qualitative approach I have followed within the research project, undertaking ethnographic fieldwork in both cities. In order to do this properly, I spent one year interviewing and observing fourteen informants in the Brussels and Berlin contemporary dance scene. Furthermore, from a dance studies perspective, in order to fully grasp the working conditions in contemporary dance through the lens of its practitioners, it was necessary to explore the performances in which contemporary dance artists in Brussels and Berlin publicly address their socio-economic position and precarious working conditions, and this as key part of the fieldwork. This book thus also discusses the emerging aesthetic of precariousness in which the precarious nature of artistic work has been made visible on stage.

In the first part of the body of this book, I juxtapose the notions of lifestyle artists and survival artists, which at first sight seem opposite terms. In the chapter on ‘Lifestyle Artists,’ I argue that a bohemian work ethic prevails among the contemporary dance artists within my fieldwork. The concept itself is oxymoronic as it consists of a combination of self-contradictory elements, including a bohemian lifestyle versus a strenuous work ethic. Drawing on my qualitative data, I outline that at least the contemporary dance artists within my fieldwork construct a habitus, where work time and private life are closely intertwined, or even depend on one another. A bohemian work ethic therefore includes the choice for an autonomous lifestyle as an artist, but simultaneously, also the ambiguous acknowledgment that this comes with actual work to ensure one’s survival in the art world. In the next chapter ‘Survival Artists,’ I discuss that in the bohemian work ethic artists have developed a variety of survival tactics so they can carry on to practice their profession despite the economic challenges affecting their work and lives. Especially, the outline of the different forms of cross-financing illustrates that in the art world, money is not an end but a means. All in all, I address several individual survival tactics that demonstrate that the contemporary dance artists in my fieldwork show themselves resilient toward the prevailing precarity in their profession. The outlined survival mode impacts not only the lives but also the artistic work of my informants. The dominant working conditions greatly affect the quality and aesthetics of an artistic work. A noteworthy consequence of the survival mode is the creation of tactical pieces and precarity solos.

The second part of the book looks at the causes and effects of the fast, mobile, and flexible modi operandi in the contemporary dance scenes in Brussels and Berlin. The first chapter on ‘The Fast’ deals with a threefold chase: a vicious cycle of chasing funding, chasing programmers, and chasing papers. Project-based subsidies engender a precarious position because one is dependent on financial support that is temporary and conditional. There is a manifold sense of uncertainty when applying for funding: you do not know if you will receive a subsidy, how much money you will be granted, and when the sum will arrive. This chase is always accompanied by precarity, since artists invest time, work effort, and often also their own money without the guarantee they will receive funding. The search for funding, and thus work opportunities, is accompanied by maintaining a network of professional contacts. As we will see, a career in contemporary dance develops between institutions rather than within one, which demands certain competences in order to sustain itself. The persistent chase after programmers, which requires networking skills, self-promotion abilities, and the application of tactics in communication can be best understood in the context of Pierre Bourdieu’s discourse on the different forms of capital (1986). In the context of this chase, the social dynamics at play prove to be fundamental in advancing contemporary dance artists’ careers, because programmers are gatekeepers who control and provide the artists’ access to support, in terms of infrastructure and production budget. The third kind of chase deals with the bureaucracy that comes hand in hand with autonomous work. In terms of social security, Belgium and Germany have quite distinctive freelancing systems in the independent arts sector. As a consequence of the bureaucratic freelancing and project-based funding systems for artists, contemporary dance artists have to deal with a fair amount of paperwork. In addition, the different international work economies in the contexts that my informants work in cause manifold administrative problems.

In the second chapter on ‘The Mobile,’ I address the mobility of contemporary dance artists in time and space, especially in uncovering the mechanism of the residency system on which most project-based contemporary dance artists have come to rely. My findings reveal several flaws of the residency system that can be generalized as well as a number of specific flaws that are linked to particular residency programs or spaces. As we will see, the general lack of time for creative work, regulated in limited time blocks, leaves only little time for research and experiment and seems to undermine the quality of the dance pieces we see on European stages.

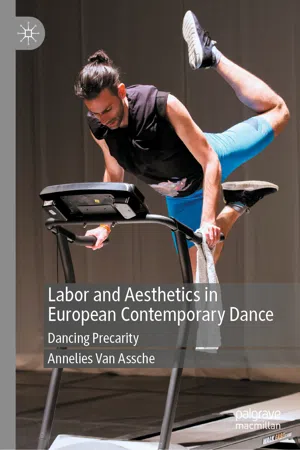

In the third chapter on ‘The Flexible,’ I discuss that a dance artist’s body ought to be polyvalent, flexible, and adaptable, but also their entire set of pragmatic transferable skills needs to be marked by polyvalence, flexibility, and adaptability in order to remain employable. This second part of the book reveals that the fast, mobile, and flexible modi operandi bring about more adaptable pieces that do not necessarily require a theater space, but in line with the neoliberal logic they can be performed anywhere and anytime. In addition, I provide an in-depth discussion of how these three dimensions are reflected in dance performance, for which I carefully selected VOLCANO (2014) by Brussels-based Liz Kinoshita as my central case.

In the third part, I address the physical and mental consequences of doing everything fast, mobile, and flexible. Essentially, I perceive this third part as the pinnacle of my research, fusing the analysis of my anonymous qualitative data with the performances of precarity I encountered during my fieldwork. In these performances, contemporary dance artists publicly address the plural forms of precarity and precarity’s penalties on one’s physical or mental state within their artistic work. In the first chapter on ‘Burning Out,’ I distinguish different levels of precarity that affect contemporary dance artists other than the already addressed socio-economic precarity. While I focus first on the body of a contemporary dance artist, I quickly move forward to quite a unique form of mental precarity prevalent in the arts: the core of artistic precarity seems to be grounded in the fact that an artist is never certain whether their work will be appreciated by a choreographer, a peer, a programmer, a critic, or an audience and whether the quality of their work is ever good enough to be considered a genuine artist. I discuss these issues with the help of the performances Only Mine Alone (2016) by Igor Koruga and Ana Dubljević and Crisis Karaoke (2016) by Jeremy Wade. I argue that the plural character of artistic precarity in the accelerated work regime oftentimes results in a twofold deceleration of burning out and slowing down.

In the last chapter ‘Slowing Down,’ I discuss several tactics of deceleration in response to overburdening or to avoid burning out by looking at Michael Helland’s performance RECESS: Dance of Light (2016). I unveil the double paradox of slowing down as a tactic of resistance against the forces of neoliberalism: ultimately, slowing down does not turn out to be subversive, because firstly it proves to be rather an accelerating form of deceleration so as to increase our productivity, and secondly, slowing down has become commodified itself. I come to conclude that the unfair and precarious working conditions contemporary dance artists specifically deal with are thus tied in with a more general point at i...