- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

From the brisk waters of Seattle to the earthy mushroom-studded forest surrounding Portland, author Darrin Nordahl takes us on a journey to expand our palates with the local flavors of the beautiful Pacific Northwest. There are a multitude of indigenous fruits, vegetables, mushrooms, and seafood waiting to be rediscovered in the luscious PNW.

Eating the Pacific Northwest looks at the unique foods that are native to the region including salmon, truffles, and of course, geoduck, among others. Festivals featured include the Oregon Truffle Festival and Dungeness Crab and Seafood Festival, and there are recipes for every ingredient, including Buttermilk Fried Oysters with Truffled Rémoulade and Nootka Roses and Salmonberries. Nordahl also discusses some of the larger agricultural, political, and ecological issues that prevent these wild, and arguably tastier foods, from reaching our table.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Eating the Pacific Northwest by Darrin Nordahl in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Culinary Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Eugene:

BLISS FOOD

Oregon black and white truffles.

To love truffles is to revel in contrast. White or black? European or American? Infused or shaved? Pigs or dogs? Just an earthborne fungus or the most nuanced, enchanting, provocative, exalted food on Earth?

You may already be quite familiar with truffles, those decadent black Périgords from France or the luxurious Italian whites from Alba; the fungi that the famed gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin once claimed were “the diamonds of the kitchen.” If so, then you can appreciate their ethereal aromas and euphoric flavor (and stratospheric prices)—but I learned something that might rock your gustatory world. I discovered something better growing in the dense, coastal, evergreen forests of Oregon. And aside from a handful of locals (and maybe Sasquatch) nobody knows about these hidden treasures … and they just may incite Oregon’s next Gold Rush.

Regardless of established French and Italian renown, let me declare with confidence that the Willamette Valley is one of the world’s best truffle regions. But this shouldn’t come as much surprise. America is maturing gastronomically. Our wines have bested France’s most vaunted, time and again. We are excelling in craft beer, cheese, and charcuterie, and Americans now roast the best coffee and cacao beans in the world. Indeed, we have mastered many techniques in creating the finest drinks and foodstuffs gourmands have ever known. And now, we might also possess one of gastronomy’s finest raw materials.

I will concede, I’m somewhat new to truffles. I had just started to delve into the mystique of these culinary gems when I came across a food celebration in the Pacific Northwest that piqued my interest, the Oregon Truffle Festival. This food festival is unique for a few reasons, one being that it is so popular. I can’t recall any other multiday foodie jubilee that is held over two weekends in two different cities. The Oregon Truffle Festival, or OTF, is a concise and casual affair in and around Portland one weekend, and then a pull-out-all-the-stops extravaganza in Eugene during another. This celebration is also different in that it is held in the dead of winter. January seemed an odd month for fresh food revelry, but then again, no better way to kick-start the new year than with a food festival of unparalleled decadence. Besides, Mother Nature doesn’t cater to our convenience; when She says the food is ready to eat, then eat we shall. And for Oregon truffles, that means winter.

The festival is also unique because of the diversity of guests it attracts: culinary artisans as well as scientists, locals and international visitors, jet-setting gourmands in natty attire alongside salt-of-the-earth growers donning flannel, denim, and muddy footwear. But the most conspicuous demographic amid the somewhat posh interior of the Eugene Hilton are those dressed in collars and fur coats: the shepherds, pointers, hounds, and retrievers.

THE TRUFFLE DOCTOR IS IN

I pulled into downtown Eugene and the weather was perfectly stereotypical for this time of year: cold, wet, and dreary. I checked into the hotel and then immediately sought one of the large conference rooms. I don’t usually attend food festivals carrying an attaché with notepads and reference materials and an audio recorder, but I had been told this first day of the festival was going to be a heady affair; not in a gastronomical sense but an intellectual one.

I walked into the conference and took an aisle seat next to a red-haired retriever lying contently on the floor. Dr. Charles Lefevre had just finished his introductory remarks, acknowledging the list of distinguished speakers here today, though Lefevre is quite distinguished himself; well-known among truffle scientists and growers throughout the world. Two years before Charles completed his doctorate in forest mycology at Oregon State, a grower from Corvallis asked him if he could inoculate hazelnut seedlings with Tuber melanosporum—the delicious fungus gourmands know better as the French black truffle, or Périgord. Charles succeeded, which garnered the attention of the Los Angeles Times, thrusting him into the public spotlight. After the media splash that there might soon be a Périgord orchard on the West Coast, demand for truffle-inoculated saplings surged, and Lefevre founded New World Truffieres, a company that produces inoculated trees for truffle orchards throughout North America. The excitement continued to build. Soon Lefevre’s promising work was featured in the New Yorker, the New York Times, Discovery Channel, Forbes, Audubon, Smithsonian, and other notable periodicals.

Dr. Charles Lefevre inspects one of his recently inoculated saplings at the Oregon Truffle Festival.

There was good reason to be excited over US-grown Périgords, but Charles believed our native truffles should be equally illustrious. In 2006, he and his wife, Leslie Scott, founded the Oregon Truffle Festival—the first truffle festival of its kind outside of Europe. It was to be more than a boisterous celebration of those delectable French and Italian fungi, however. The founding of the OTF was rooted in science and education, as a participatory event that could help grow the burgeoning truffle cultivation industry in North America through symposia, led by the brightest minds in botany, forest ecology, and mycology. But it was also an opportunity for Charles and Leslie to showcase the specialness of Oregon truffles.

Today, at the Truffle Growers Forum, Lefevre’s invited guests were going to expound on truffle culture, sharing trials and insights of cultivating truffles in their respective corners of the world: Japan, Australia, Canada, and Spain. This was going to be a serious day of discussion—because there is serious money to made with truffles.

For a truffle newbie like myself, there were numerous nuggets of information to be gleaned from these expert discussions. I had already known that a truffle is the fruiting body of a fungus that lives in symbiosis with tree roots. The fungus explores the soil for water and minerals, which it passes along to the tree. In exchange, the tree provides sugars produced through photosynthesis to the fungus. Many tree species can serve as hosts for European truffles, and the most common are oak and hazelnut, but also chestnut, elm, beech, and poplar.

What I didn’t know is that, in the Willamette Valley, there is just one tree that the native truffles latch onto, the coast Douglas fir, the state tree of Oregon. Since the coast Douglas fir’s range is compact and delimited—it grows only in that narrow band of the Pacific coast temperate rainforest between Vancouver Island and Northern California, and west of the Cascades to the Pacific Ocean—Oregon truffles are a distinct, place-based delicacy.

One of the panel discussions focused on truffle aroma and the science behind those captivating smells. Dr. Lefevre was joined by Harold McGee an American author famous for his work on the chemistry of food science and cookery. McGee’s seminal book, On Food and Cooking, influenced some of the world’s top culinary talent, including NYC’s Daniel Boulud and Britain’s Heston Blumenthal. Alton Brown describes McGee’s book as “the Rosetta stone of the culinary world.”

McGee was contrasting the aromas of Oregon white truffles with those luxurious ones from Alba, Italy. “Other than a funky animal note, Oregon truffles don’t bear any resemblance to Albas,” he noted. “With the Italian varieties, there is a sulphur, asafetida-like smell as soon as the mushroom comes out of the ground, but not so with the Oregon whites.” (Asafetida is a common spice in savory Indian cuisine, and, as the name implies, it has a fetid smell before it is cooked. It is also known as “devil’s dung.”) But when McGee inhales the scent of fresh Oregon white truffles, he immediately smells tropical fruit. “I get hints of pineapple, but then it’s gone. Now it’s more like barnyard, but that, too, is fleeting. Now it’s back to exotic fruit … is it mango?” McGee says Oregon truffles are beguiling shapeshifters. “As soon as you recognize one thing,” he says, “it morphs into the next.”

McGee then posited, “Why do truffles emit these notes?” Lefevre jumped in, “Because truffles want to be found. They need us to like them.”

Mycological reproduction is the reason truffles smell so amazing. Since they grow at the base of trees, under the duff, they are completely hidden from view. Unlike mushrooms, which poke above the forest floor and rely on wind to spread their spores, truffles need something to announce, “Hey, I’m down here, come find me!” So, they toss thousands of intensely aromatic compounds into the air, alluring scents that attract fungivores—forest critters that love eating mushrooms and truffles, like boars and jays and slugs, and, of course, humans. These aromatic compounds help ward off predators—bacteria and other fungi, namely—while attracting animals to ensure dissemination.

Interestingly, there aren’t any poisonous truffles, as there are with mushrooms, because “there is no biological benefit of killing the thing that ensures procreation,” explains Lefevre. However, some truffle varieties are vastly more aromatic than others, and thus, more appealing to us.

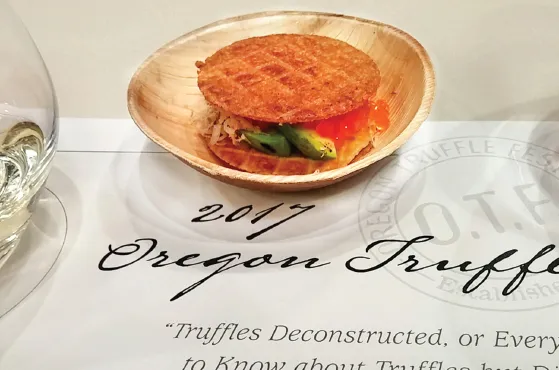

As a panel of experts discuss truffle reproduction at the Oregon Truffle Festival, the guests enjoy crisp potato wafers sandwiching smoked salmon roe, grilled avocado, and fresh Oregon white truffle shavings.

But there is no need to broadcast these bewitching aromas unless the truffle is mature and ready to reproduce; in other words, ripe. And this has been a ubiquitous concern for champions of Oregon truffles. “A few years ago, Oregon truffles weren’t interesting; completely forgettable,” recalls McGee. “But that has changed with the Oregon Truffle Festival.” McGee credits Lefevre for introducing chefs and gourmands to good, ripe Oregon truffles. Which makes all the difference between a forgettable fungus and one that fetches hundreds of dollars per pound. “Smelling a ripe Oregon truffle can be like tasting your first ripe papaya or mango or pineapple,” McGee says. “And then you realize, there’s something exotic growing right under our feet!”

Any produce with which we are not familiar, whether fruit or fungus, we must learn when it is ready for harvest. Unlike tomatoes or bell peppers, truffles have no culinary value unless they are completely ripe. But truffles don’t turn red to let us know when we should eat them. Instead, we must rely on aroma. Until we know what aromas we should be smelling, any unearthed truffle that lacks those heady scents might be castigated, tossed aside, and forgotten because we wrongly assumed they were inferior. Such has been the legacy of Oregon truffles; that is, until the OTF.

Though our nose is the best gauge for determining truffle ripeness, there are clues we can see. One way to tell if a truffle is ripe is to peek inside. Truffle exteriors are rough, dusky, and pimply, but inside, the fruit reminds me of the finest granite, beautifully speckled, with white venation permeating a rich buff color in the case of white truffles or a deep mocha brown in the case of black. Venation complexity and clarity improves as the fruit ripens. To determine when a truffle is ripe, take a pocketknife, flick off a pimple, and look for contrast. When the browns are dark and the white veins are stark and clear—no blurring or muddying—the truffle is ready.

We can also rely on our sense of sight (and touch) when determining if a truffle has peaked and is starting to decay. Charles says recognizing this trait is the most important, because a truffle will continue to improve—ripen—even when those ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue: Identity Crisis

- Introduction: What is the Pacific Northwest?

- 1. Eugene: Bliss Food

- 2. Shelton: From Tide to Table

- 3. Olympia: It’s the Water

- 4. Port Angeles: Lobster of the Pacific

- 5. Portland: Bounty in the Bramble

- 6. Seattle: King of Kings

- 7. Lummi Island: Hyperlocal

- Resources: When You Go