eBook - ePub

Watching the Watchers

Parliament and the Intelligence Services

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This study offers the first detailed examination of the varied means by which parliament through its committees and the work of individual members has sought to scrutinise the British intelligence and security agencies and the government's use of intelligence.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Watching the Watchers by H. Bochel,A. Defty,J. Kirkpatrick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: The Challenges of Legislative Oversight of Intelligence

On 24 September 2002, Tony Blair, the British Prime Minister, walked into the House of Commons carrying under his arm a dossier comprising intelligence on Iraqi weapons of mass destruction. The dossier had been published earlier that day to coincide with the recall of Parliament to debate policy towards Iraq. As the Butler Inquiry later observed, the so-called September dossier broke new ground by using secret intelligence in a public document in order to make a case for international action (Butler, 2004). While there were significant reservations within Parliament about the need for military action, there was broad acceptance of the information included in the dossier. When, almost eleven years later to the day, David Cameron, the Conservative Prime Minister of a coalition government, stood before a recalled House of Commons to seek parliamentary support for military action in Syria, the Prime Minister once again invoked the ‘key independent judgements of the Joint Intelligence Committee’ (JIC) (Hansard – 29 August 2013, col. 1426), which this time took the form of a letter from the Chair of the JIC. On this occasion, however, Parliament was less accepting of that evidence, and the overwhelming response of those MPs who voted against military action was to press the government to publish more intelligence.

What these two cases illustrate is both the willingness of governments to place intelligence before Parliament in order to generate support for policy, and also an apparent increase in Parliament’s appetite to view such material. However, what is less clear is whether Parliament’s capacity to scrutinise intelligence has improved since 2002. One of the Butler Inquiry’s key lessons in relation to the use of intelligence to support the case for war in Iraq was that ‘if intelligence is to be used more widely by governments in public debate in the future, those doing so must be careful to explain its uses and limitations’ (Butler, 2004, p. 155). Parliament is increasingly involved in the scrutiny of legislation and policy related to the use of intelligence. While this clearly includes significant decisions, such as whether to engage in military action, it also extends to legislation and policy relating to the government’s use of intelligence and the actions of the intelligence and security agencies in a range of areas such as anti-terrorism, the interception of communications and the operation of the courts. Some parliamentarians also play a direct and significant role in the oversight of the intelligence and security agencies, both as ministers and, since 1994, as members of the Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC). However, while Parliament and its members are increasingly involved in the scrutiny of intelligence at various levels, and there has arguably been an increase in Parliament’s appetite for information about the intelligence underpinning policy, the extent to which Parliament is effective in scrutinising intelligence issues is far from clear.

This book provides a new and detailed examination of parliamentary scrutiny of the British intelligence and security agencies, and policy. Through analysis of parliamentary business, coupled with interviews with more than 100 MPs and Peers (including more than 50 from each House) and a number of senior officials, it examines the various mechanisms by which Parliament seeks to scrutinise the intelligence and security agencies, and more broadly, governments’ use of intelligence. While previous studies have tended to focus almost exclusively on parliamentary oversight of the intelligence and security agencies, and in particular on the operation of the ISC, this book adopts a wider focus. This broad approach is not only new, but is significant for a number of reasons: firstly, while the ISC is responsible for scrutinising the work of the intelligence and security agencies, Parliament as a whole is increasingly involved in the scrutiny of legislation, or policy, which relates to the activities of the agencies or the government’s use of intelligence; secondly, as Parliament provides the personnel from which the government is formed, a clear understanding of the work of the agencies and the nature and limitations of intelligence, beyond those directly involved in oversight, is clearly important; thirdly, while there is increasing pressure from within Parliament for greater parliamentary scrutiny of intelligence, as noted above, the capacity of Parliament to provide effective scrutiny in this area is not clear; finally, by seeking to move away from the notion that legislative scrutiny of intelligence is a distinct and specialist field, the research presented here draws on existing models of parliamentary scrutiny and also seeks to feed into wider debates about the ability of Parliament to hold the executive to account.

This is a study of parliamentary scrutiny of the British intelligence and security agencies. The remainder of this chapter seeks to place that study within a number of wider contexts. Legislative scrutiny is only one possible form of intelligence oversight, and the relationship of legislative bodies to other possible oversight mechanisms is examined below. The development of legislative oversight in Britain is also placed within the context of its development in other states in order to draw out some of the issues and challenges associated with legislative oversight, and also possible solutions. The chapter also expands upon existing studies of legislative oversight by outlining the peculiarities of oversight in parliamentary systems, and provides a more expansive explanation of the need for a broader focus in this context. Finally, it concludes by examining some of the challenges which face researchers seeking to examine legislative oversight of intelligence.

Legislative oversight of intelligence agencies

Intelligence oversight is generally defined as a process of supervision designed to ensure that intelligence agencies do not break the law or abuse the rights of individuals at home or abroad. It also ensures that agencies are managed efficiently, and that money is spent properly and wisely. There is, however, no one model of intelligence oversight. It does, of necessity, vary from country to country, and may be affected and defined by a state’s history, constitutional and legal systems, and political culture. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify a range of institutions and actors that may be involved in the oversight of intelligence and security agencies. By far the most detailed account of the role of the various institutions and actors which might be involved has been provided by Born and Leigh (2005), who, as noted above, argue that oversight is typically seen as taking place at several different levels. According to them, each actor or oversight institution has a different function:

The executive controls the services by giving direction to them, including tasking, prioritising and making resources available. Additionally, the parliament focuses on oversight, which is limited to more general issues and authorisation of the budget. The parliament is more reactive when setting up committees of inquiry to investigate scandals. The judiciary is tasked with monitoring the use of special powers (next to adjudicating wrong-doings). Civil society, think-tanks and citizens may restrain the functioning of the services by giving an alternative view (think-tanks), disclosing scandals and crises (media), or by raising complaints concerning wrong-doing (citizens). (Born and Leigh, 2005, p. 15)

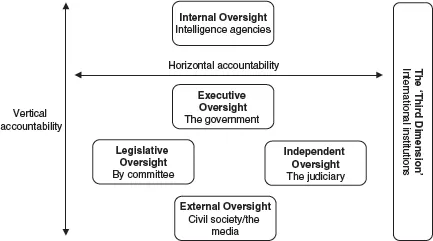

Building on the work of Born and Leigh, and drawing on a broader literature on the accountability of public institutions, Caparini (2007) has examined the relationship between the various levels of oversight and provided a framework for accountability of intelligence and security agencies based on three different types of accountability: horizontal, vertical and the ‘third dimension’. Horizontal accountability is used to describe the restraint of state institutions by other state institutions, and might therefore include executive, legislative and judicial oversight of intelligence agencies. Vertical accountability refers to the hierarchical relationships between different accountability mechanisms. This allows one to differentiate between the level of access and control exerted by, for example, executive and legislative oversight bodies. Vertical accountability also takes account of scrutiny by non-state actors, such as the media and civil society organisations, and the role of citizens in holding elected representatives to account. The ‘third dimension’ refers to the role of international actors, such as foreign governments, intergovernmental and non-governmental institutions (Caparini, 2007). This work allows the identification of a range of institutions and actors with a role in the oversight of intelligence, and that oversight is typically seen to take place at several different levels (Figure 1.1).

Legislative scrutiny is, then, only one of a number of possible mechanisms for oversight of intelligence agencies. Nevertheless, it is widely viewed as central because it provides democratic accountability and legitimacy. At a minimum, the passage of legislation to place intelligence agencies and their activities on a statutory footing ensures that the existence and role of the agencies has been the subject of parliamentary debate, that the agencies are subject to the law, and that their activities are placed within an existing constitutional framework. In many cases such legislation has also provided for an ongoing process of legislative scrutiny. Such ongoing scrutiny often places intelligence and security on a par with other areas of public policy, ensuring that, as Leigh observes, the intelligence and security sector is not a ‘zone sanitaire for democratic scrutiny’ (Leigh, 2009, p. 71). Legislative oversight has some similarities to executive oversight, in that it provides for scrutiny by democratically elected politicians. However, in contrast to executive scrutiny, legislative oversight usually involves individuals who are not involved in the process of tasking the intelligence agencies. As a result it should help to ensure that intelligence agencies are not subject to political pressure, or used to further particular political interests, rather than the security of the state as a whole. Legislative oversight may also be valuable in maintaining public confidence in the intelligence and security agencies. The very existence of legislative oversight bodies may serve to reassure the public that intelligence agencies are not abusing their powers. Moreover, the operation of legislative oversight bodies may be more open and accessible than internal or executive scrutiny, allowing oversight to be seen to be taking place.

Figure 1.1 Levels of intelligence oversight

Legislative oversight of intelligence agencies is not, however, without its challenges. Securing the trust of the agencies can be a significant task for legislative oversight bodies. There is also a risk that parliamentarians will seek to manipulate the process of oversight to gain political advantage, and perhaps most significantly, that parliamentarians who may not be accustomed to handling classified materials, may, either by accident or intent, leak secret information. Legislative oversight of intelligence may also pose challenges to those involved. Given that most parliamentarians, like most citizens, have little experience of the activities, or indeed the role of the intelligence and security agencies, providing effective and rigorous scrutiny may be hampered by a lack of expertise. Moreover, because those involved may be approaching their subject from a much lower knowledge base than for some policy areas, the development of expertise may involve a rather steeper learning curve than in other areas of legislative scrutiny, and as a result there is also a danger that they may be more easily misled or diverted from asking difficult questions. Related to this, another potential problem is that those involved in legislative oversight of intelligence agencies may be seduced by privileged access and become too close to those they are responsible for scrutinising. The challenges involved in developing trust, knowledge and detachment, while not unique to the scrutiny of intelligence, may therefore be exacerbated by the particular nature of the subject.

Fears that parliamentarians would seek to manipulate the process of oversight to gain political advantage, and, perhaps crucially, that parliamentarians could not be trusted not to leak sensitive material, have meant that many states have avoided the use of existing parliamentary mechanisms, such as select committees, and have sought instead to create special legislative oversight bodies. These have taken a variety of forms. A number of states resisted traditional parliamentary oversight in favour of external review bodies appointed by Parliament. Canada and Norway, for example, have external intelligence oversight bodies consisting of panels of independent experts appointed by, but operating at arm’s length from, Parliament (Farson, 2005; Mevik and Huus-Hansen, 2007). Other states, including the Netherlands, South Africa and the United Kingdom, responded by creating special committees comprising a small number of trusted parliamentarians, appointed by the executive, to act as a proxy for wider legislative scrutiny (O’Brien, 2005; Wiegers and van Hees, 2007). Members of oversight committees may also be subject to security vetting above and beyond that applied to those scrutinising other policy areas. However, the sensitivity involved in subjecting parliamentarians to scrutiny by intelligence agencies means that in some cases intelligence oversight committee members are required instead to operate under oath. In the UK, for example, members of the ISC are required to sign the Official Secrets Act, something which is also required of serving government ministers, but which is not applied to members of other parliamentary committees.

In many states the mandates of legislative intelligence oversight bodies are circumscribed, particularly when compared with committees scrutinising other policy areas. One common distinction relates to whether or not intelligence oversight committees examine operational matters, or focus solely on the effectiveness or efficiency of intelligence agencies (Born and Leigh, 2005). Another relates to whether committees examine the legality of intelligence activities, or concern themselves largely with administrative matters. Powerful, long-standing oversight committees, such as those of the US and Germany, have wide-ranging powers to examine intelligence policies and operations in order to determine legality and effectiveness. Oversight committees with more limited mandates, such as those in the UK and Australia, are prevented from scrutinising operational matters and focus primarily on the efficacy of intelligence administration and policy, although in practice, both the British and Australian parliamentary oversight bodies have, on occasion, examined operational matters at the request of the executive (King, 2001; Born and Leigh, 2005).

There is also considerable variation in the powers available to legislative oversight bodies to access intelligence documents and staff. In some cases this reflects existing constitutional arrangements. The constitutional checks and balances embedded in the US system, for example, provide US congressional intelligence committees with wide-ranging powers to hold the executive to account, although they have not always chosen to exercise them (Johnson, 2005; Zegart, 2011). However, in some countries special arrangements have been applied which differ from the powers exercised by other legislative committees. The ISC in the UK, for example, has not had the same powers as parliamentary select committees to call for ‘people, papers and records’, and until reforms introduced in 2013, intelligence agency heads had the power to deny the Committee access to ‘sensitive information’, although this was rarely exercised (Gill, 2005). The powers of oversight committees may also be circumscribed by the resources available to them. While those involved in intelligence oversight often look with envy at the resources deployed by US congressional oversight committees, Born and Johnson have observed that most intelligence oversight committees have limited resources and staff, possibly because ‘the creators of the selected oversight bodies have been hesitant to set up a counter-bureaucracy responsible for reviewing the intelligence bureaucracy’ (2005, p. 238).

Although there is considerable variation in the form and operation of legislative intelligence oversight bodies, some form of legislative oversight has become the norm in most democratic states. As Gill and Phythian observe, ‘the idea of Parliament itself providing the core of oversight structures, if not the only one, is more or less universal’ (2006, p. 158). In addition to the US, where legislative oversight has a long history, parliamentary committees are now to be found throughout Western Europe, in most post-communist states in Europe, South Africa and several large Latin American states (Born and Caparini, 2007).

The near universal acceptance of the need for democratic oversight does not, however, mark the end of a process of intelligence accountability. In many states legislative intelligence oversight mechanisms have continued to evolve as oversight committees have sought extra powers and developed new roles. In many cases this evolution has seen a movement away from legislative scrutiny of intelligence being viewed as somehow different from the scrutiny of other policy areas, towards making the operation of legislative intelligence oversight committees more like that of other oversight committees. The most obvious example of this is the US, where congressional oversight of intelligence originated in an ad hoc subcommittee comprising the most senior members of the Senate Armed Services Committee, and has evolved into two standing congressional oversight committees (Snider, 2008). In the UK, in 2007 the Labour government published a Green Paper in which it recommended that the way in which the ISC operated should be brought as far as possible into line with that of other parliamentary committees, while more recent reforms, discussed later in this book, have seen the Committee reconstituted as a standing committee of Parliament. A similar debate has taken place in Canada, where dissatisfaction with the peculiar nature of an external review committee which reports to Parliament has led to calls for the establishment of a committee of parliamentarians, albeit on the British model, and the establishment of a Senate Committee on National Security and Defence. Such developments highlight that the process of legislative oversight of intelligence is a dynamic one in which legislative oversight committees do not operate in isolation from existing parliamentary bodies. Whether or not legislative intelligence oversight committees were established with a distinct and special mandate, such committees often find themselves working within existing parliamentary structures. This can mean that, as they evolve, changes in one may impact or influence the work of the other, and suggests that in examining legislative oversight of intelligence a broader framework for analysis may be necessary, rather than one which focuses solely on the work of discrete intelligence scrutiny committees.

Legislative oversight of intelligence in the UK: the need for a broader focus

As has already been noted, existing studies of legislative oversight of intelligence have tended to focus on the institutional frameworks for oversight, and in particular on the form, mandate, membership and powers of the intelligence oversight committees (Born and Leigh, 2005; Gill, 2007). This has been particularly the case in the UK, where studies of legislative oversight of intelligence have focused almost exclusively on the work of the ISC (for example, Glees, Davies and Morrison, 2006; Gill, 2007; Leigh, 2007; Phythian 2010). Moreover, the emphasis on different levels of oversight has implied a separation between the various institutions in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: The Challenges of Legislative Oversight of Intelligence

- 2 ‘The Government Does Not Comment…’: Parliament and the Intelligence Services

- 3 Managing Continuity and Change: Legislating for Intelligence Agency Accountability

- 4 ‘A Unique and Special Committee’: The Intelligence and Security Committee

- 5 Issues of Accountability and Access: The Select Committees and Intelligence

- 6 Other Indicators of Parliamentary Interest: Debates, Questions, Motions and Groups

- 7 ‘No Longer Scared to Ask…’: Parliamentarians and the Intelligence Services

- 8 New Possibilities: Legislative Oversight of Intelligence beyond Westminster

- 9 Conclusions: Parliament and the Future of Intelligence Oversight

- Bibliography

- Index