eBook - ePub

Growing Income Inequalities

Economic Analyses

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book explores the widening gap between the wage packets of skilled and unskilled workers that has become a pressing issue for all states in the globalized world economy. Comparing the experiences of more and less developed economies, chapters analyse the underlying causes and key social changes that accompany income inequality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Growing Income Inequalities by J. Hellier, N. Chusseau, J. Hellier,N. Chusseau in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Where Do We Stand? Why Is It So?

1

Growing Income Inequalities in Advanced Countries

Nathalie Chusseau and Michel Dumont

1.1Introduction

Since the early eighties, advanced countries have experienced an increase in wage inequalities between skilled and unskilled workers. The economic literature has proposed several explanations for this increase. This canbe implemented fromaDemand-Supply-Institution framework (Katz and Autor, 1999; Acemoglu, 1998, 2005). Considering the markets for skilled and unskilled labour, any factor that modifies the demands for and supplies of skilled and unskilled workers indeed affects the skill premium (ratio of the wage of skilled on the wage of unskilled workers), and thus the inequality between skilled and unskilled workers. Supply-side factors such as education, training, skill obsolescence, migration and demand-side factors have been analysed and estimated in an abundant literature.

In advanced countries, the increase in wage inequality between skilled and unskilled workers has coincided with:

(i)a growing unemployment gap between skilled and unskilled workers, and

(ii)an increase in the relative supply of skilled labour (except in the US where its progression slowed down in the 1990s).

The concomitance of these three developments reveals that the demand for skilled labour has grown critically faster than the demand for unskilled labour. The economic literature has thus focused on changes affecting the demand side. Three main explanations have been put forward. The first is based on technological change which is considered as skill-biased, i.e., as augmenting the demand for skilled in relation to the demand for less-skilled workers. The second is the development of North–South trade (NST) analysed within a Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson (HOS) framework, with the ‘South’ (less developed countries) being characterized by a high proportion of unskilled labour with low wages, which leads to a reduction of the unskilled workers’ wages in the North. The third centres on institutional changes on the labour market. In fact, institutions impact (i) on the demand for and the supply of skilled and unskilled labour and (ii) on the adjustment between supply and demand.

A large amount of literature has been devotedto estimating the impacts of technology, trade and institutions upon growing wage inequalities. The early empirical estimates typically result in the following diagnosis: (i) a significant influence from technological change, (ii) a non-negligible impact of institutions in certain countries (the US and the UK), and (iii) a small impact from North–South trade. However, these early estimates contained several shortcomings: (i) the empirical methods were controversial; (ii) technological change was exogenous; (iii) technological differences between the North and the South and international outsourcing were overlooked; (iv) technical change, NST and labour market institutions were considered as independent from each other, and (v) certain stylized facts such as labour market polarization remained unexplained. Finally, since the mid-1990s, a series of new estimates have questioned the early diagnosis.

Consequently, a new wave of empirical and theoretical approaches (i) have modelled and estimated the operating mechanisms of skill-biased technological change, North–South trade and institutional changes, and (ii) have considered possible interactions between labour supply and technological change, institutions and technological change and trade and technology.

This chapter presents a review of both theoretical and empirical literature on explaining growing inequalities in advanced countries. Section 1.2 explores a number of stylized facts. Section 1.3 depicts the Demand-Supply-Institution analytical framework, and Section 1.4 examines the three main explanations based on technological bias and North–South trade (demand-sided explanations), and on the changes in labour market institutions. Finally, Section 1.5 exposes the alternative mechanisms developed in the new theoretical and empirical literature. We conclude in Section 1.6.

1.2Stylized facts

Since the early 1980s, most OECD countries have witnessed a number of noticeable trends:

1.An increase in income and wage inequality, particularly between high-skilled and low-skilled labour;

2.A step-up in international economic integration characterized by a growing weight from developing countries in both production and trade of manufactured goods, and a transfer to the South of low-skilled intensive stages of production (international outsourcing or offshoring);

3.Major technological change, especially in the spread of information and communication technologies (ICT) throughout all industries;

4.A strengthening in labour market flexibility with a material deterioration in (i) union density, (ii) the level of the minimum wage in relation to median wage and (iii) employment protection;

5.A continuous increase in the educational level of the working population.

1.2.1Growing wage inequality

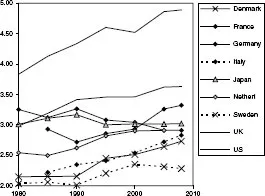

Figure 1.1 shows that since the early eighties, most of the advanced countries have experienced a widening of wage inequalities measured by the percentile ratio P90/P10. However, the intensity of this increase critically differs across countries. The most severe increase in inequality can be observed in the US and the UK. Nordic countries (Denmark2, Finland, Norway and Sweden) and the Netherlands have witnessed a rather moderate increase and inequality still remains low in these economies. Western Continental Europe (Belgium, France, Germany) and Japan have experienced either a low increase, or a stagnation in inequality during the last 30 years, and their inequality lies between the Scandinavian and the Anglo-Saxon (and Southern Europe) levels. A non-negligible increase in inequality can however be observed in Germany dating back to the late 1990s.

Figure 1.1Ratio P90/P101 in 11 advanced countries, 1979–2008 (Source OECD)

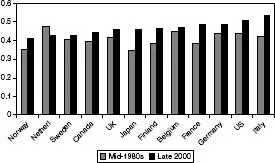

Figure 1.2 Gini of Incomes (before taxes and transfers), 12 advanced countries

Source OECD Income Distribution-Inequality data.

Source OECD Income Distribution-Inequality data.

1.2.2Growing income inequality

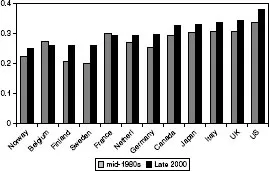

Figure 1.2 shows that the income inequality before taxes and transfers has increased between the mid-1980s and late 2000 in almost all OECD countries, except for the Netherlands. This increase is particularly high for France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the US. The comparison with the evolution of income inequality after taxes and transfers (Figure 1.3) shows that these policies transform (i) the level of income inequality, which suggests that redistributive policies are effective in advanced countries, and (ii) the hierarchy between the countries. The least egalitarian countries are the US, the UK and Italy whereas, after taxes, the Scandinavian countries and Belgium remain the most egalitarian. Somewhat remarkably, whereas income inequality before taxes has decreased in the Netherlands, it has increased after taxes.

Figure 1.3Gini of Incomes (after taxes and transfers), 12 advanced countries

Source OECD Income Distribution-Inequality data.

Source OECD Income Distribution-Inequality data.

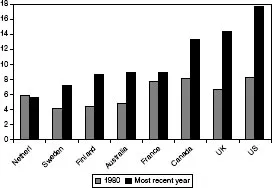

Figure 1.4Share of top 1% incomes in total income, 8 advanced countries

Source The World Top Incomes Database. The most recent year ranges from 2004 to 2008.

Source The World Top Incomes Database. The most recent year ranges from 2004 to 2008.

Finally, the recently developed World Top Incomes database reveals a substantial rise of the income share at the top of the income distribution, especially in Anglo-Saxon countries but also in some Scandinavian countries as shown in Figure 1.4.

1.2.3Globalization and North–South trade

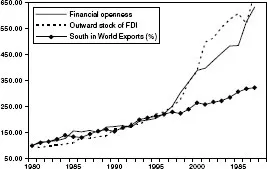

Figure 1.5 shows the evolution of three indicators of globalization: (i) financial openness defined as the sum of cross-border liabilities and assets as a percentage of GDP for OECD countries, (ii) the outward stocks of FDI (in percent of GDP, OECD countries) and (iii) the share of the South3 in World manufacturing exports. These three indicators have dramatically increased since the early 1980s.

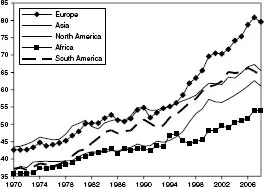

Dreher (2006 a,b) has proposed a synthetic globalization index (KOF) that combines the economic, social and political dimensions of globalization. The index of economic globalization is a weighted sum of variables reflecting actual flows and restrictions. International trade, FDI, portfolio investment and income payments to foreign nationals are considered for the globalization indicator of actual flows. Figure 1.6 depicts the variation in the economic index since 1970.

All these indicators clearly demonstrate the existence of a globalization process which has significantly gathered space since the early 1990s.

Figure 1.5Indicators of globalization (1980 = 100)

Source OECD (2011) for Financial Openness and FDI; CHELEM database for the South in world exports (%).

Figure 1.6KOF economic globalization Index by continent (1970–2008)

Source http://globalization.kof.ethz.ch/aggregation/. The indicator is the weighted sum of international trade (22%); Foreign Direct Investment stocks (29%); Portfolio Investment (22%) and Income Payments to Foreign Nationals (27%), as a percentage of GDP (see Dreher, 2006, and Dreher and Gaston, 2008).

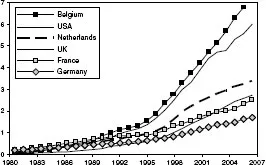

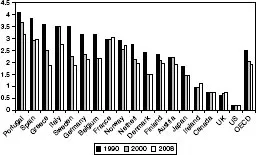

Figure 1.7ICT capital services per hour worked in manufacturing, 6 advanced countries

Source EU KLEMS (http://www.euklems.net/).

1.2.4A major technological change

Figure 1.7 depicts ICT (information and communication technologies) capital services per hour worked in manufacturing industries for a selection of OECD countries over the period 1980–2007. The use of ICT clearly took off in the early 1990s. There are substantial differences between countries, with a surge in Belgium and the USA and more moderate although still considerable increases in the UK, France and Germany.

1.2.5Changes in labour market institutions: more flexibility

Since the 1980s, labour markets have become more flexible in advanced countries. These countries are characterized by:

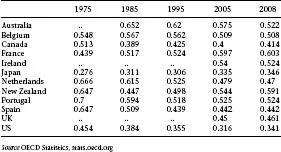

1.A decrease in the level of the minimum wage in relation to median wage (Table 1.1)

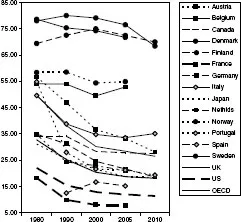

2.A decline in trade union membership, measured by the union rates (percentage of union members in the working population), as depicted in Figure 1.8.

3.A relaxation of the legislation on employment protection (Figure 1.9).

1.2.6Changes in the labour supply: a general skill upgrading

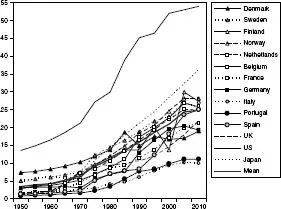

As shown in Figure 1.10, the percentage of the population with a tertiary education degree has critically increased in all OECD countries. However, the levels as well as the evolution differ across countries.

Table 1.1 Ratio minimum wage/median wageinadvanced countries, 1975–2008.

Figure 1.8Union rates in advanced countries, 1980–2010

Source OECD Statistics, stats.oecd.org

Figure 1.9Change in employment protection in advanced countries, 1980–2010

Source OECD Statistics, stats.oecd.org

Figure 1.10Percentage of the population over 25 with tertiary education (1970–2010)

Source Barro and Lee (2010), http://www.barrolee.com

1.3The demand–supply–institution framework

A supply-demand-institution framework (Freeman and Katz, 1994; Katz and Autor, 1999; Acemoglu, 1998, 2005; see also Introduction) is used to explain increasing wage and unemployment inequalities between skilled and unskilled workers. This approach considers a heterogeneous labour market with two...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction and Overview

- Part I Where Do We Stand? Why Is It So?

- Part II Globalization, Technical Change and Inequality

- Part III Inequality, Institutions and the Labour Markets

- Part IV Inequality, Education and Growth

- Index of Authors

- Index of Words