eBook - ePub

The Future of Foreign Aid

Development Cooperation and the New Geography of Global Poverty

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Future of Foreign Aid

Development Cooperation and the New Geography of Global Poverty

About this book

Sumner and Mallett review the literature on aid in light of shifts in the aid system and the increasing concentration of the world's poor in middle-income countries. As a consequence, they propose a series of practical, policy relevant options for future development cooperation, with the aim of provoking discussion and informing policy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Future of Foreign Aid by A. Sumner,R. Mallett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Aid 1.0

1

What Is Aid?

Abstract: In this opening chapter, we argue that the aid system can be usefully viewed as a market characterised by a series of factors which determine the supply of and demand for aid. Such an approach helps us identify the multiple, overlapping (and sometimes competing) objectives of aid. The chapter also explores the wide range of aid instruments on offer and traces recent shifts and evolutions in the landscape of aid.

Sumner, Andy and Mallett, Richard. The Future of Foreign Aid: Development Cooperation and the New Geography of Global Poverty. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. DOI: 10.1057/9781137298881

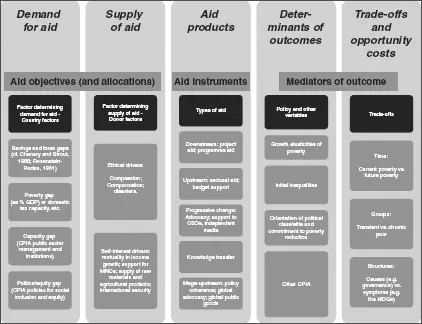

One way to approach the huge array of writing and research on foreign aid is to draw upon the concept of ‘aid markets’ (see for discussion, Barder, 2009a; Djankov et al., 2009; Dudley & Montmarquette, 1976; Easterly, 2002; Klein & Harford, 2005a). This model views the aid system as a market characterised by factors determining the demand and supply of a set of aid ‘products’. It also recognises the political economy intrinsic to all markets. This should not be taken too literally, however: as Abegaz (2005: 437) notes, ‘the market metaphor is not always apt, but it is still useful to recast the aid relationship as the interplay of demand (uses) and supply (sources)’.

Sketching out the aid market, Barder (2009a) argues that problems with aid are largely due to imperfect markets. More specifically, he discusses incomplete information, ‘broken feedback loops’, multiple and competing objectives, principal-agent problems (i.e. the interests of aid funders versus the interests of staff of aid agencies), and collective action problems. In order to improve the way aid markets function, ‘market mechanisms should be complemented by international cooperation on regulatory frameworks, and investments in networked collaboration to increase access to information and draw on the wisdom of crowds’ (Barder, 2009a: 3).

One could argue that the global aid market is constructed around the interaction of five stylised aspects: the demand for aid; the supply of aid; aid ‘products’ or instruments; aid effectiveness determinants; and trade-offs or opportunity costs (see Figure 1.1). We deal below directly with the demand for and supply of aid, and discuss aid instruments and issues around the domains of aid utility and trade-offs throughout this book.

The demand for aid is generated by some determination of recipient ‘need’. This was originally conceptualised as the ‘savings gap’ and ‘foreign exchange (forex) gap’ (cf. Chenery & Strout, 1966; Chenery & Eckstein, 1970; Griffin, 1970; Papanek, 1973; Rosenstein-Rodan, 1961). However, one could add several more gaps in terms of ‘need’, such as a ‘poverty gap’ (the cost to end poverty in the country, in terms of the number of poor people multiplied by their average distance from the poverty line); a ‘capacity gap’ (the ability to deliver poverty reduction, perhaps proxied imperfectly by the World Bank’s data on ‘quality of public administration’); and a ‘politics gap’ (meaning the elite’s commitment to poverty reduction, proxied imperfectly by the World Bank’s data on ‘social inclusion and equity’). Such gaps will differ to some considerable extent within LICs, MICs and fragile and conflict-affected states (FCAS).

Figure 1.1 Aid markets: an analytical map

Sources: Barder, 2009a; 2009b; Burnside & Dollar, 2000; Collier & Dollar, 2001; 2002; Llavador & Roemer, 2001; Mosley et al., 2004; Sayanak & Lahiri, 2009; Verschoor & Kalwij, 2006.

Of course, the demand for aid is also generated via rent seeking and other means (proxied, once again imperfectly, by the World Bank’s data on ‘transparency, accountability and corruption in public sector’ ratings).

The supply of aid is closely related to why donors give aid. On this, Sumner and Tribe (2011) suggest there are two main reasons (which break down further): an ‘ethics/compensation driver’; and ‘a self-interest driver’. Again, these will differ by LIC/MIC/FCAS, but they will also differ by ‘new’ donors (such as India, Brazil and China) versus ‘old/traditional’ donors, Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD-DAC).

Further, on the question of why aid agencies exist, Barder (2009a: 8–9) identifies three key reasons relating to reducing the cost of delivering aid: i) to mediate the competing interests of donors, recipients and others; ii) to reduce transaction and information costs; and iii) to achieve returns to scale in aid management, particularly in terms of knowledge, expertise and systems. Of course, the supply for aid is also generated via geopolitical interests and the personal views of ministers.

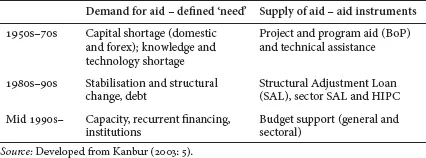

Table 1.1 A history of aid by defined ‘needs’ and aid responses

Such an approach resonates with Kanbur’s (2003: 5) discussion of the history of aid and the shifting demand for, and supply of, aid over time (see Table 1.1).

Normative definitions of foreign aid remain relatively conventional despite a changing world (Severino & Ray, 2009). As Radelet (2006: 4) explains, the standard definition of aid generally comes from the OECD-DAC: ‘financial flows, technical assistance, and commodities that are (1) designed to promote economic development and welfare as their main objective … and (2) are provided as either grants or subsidised loans’. Grants and subsidised loans (where there is a ‘grant element’ of at least 25%) are categorised as concessional financing, whereas loans that carry market terms are considered non-concessional financing.

Official Development Assistance (ODA) is the most widely recognised form of aid. In 2010, the total ODA contributed by DAC countries was 129 billion USD, or roughly 0.32% of DAC Gross National Income (still way off the UN-endorsed 0.7% target). In addition, it has been estimated by Kharas (2007: 7) that, outside the DAC, at least 29 other countries are giving ‘significant amounts’ of aid annually, including Brazil, Russia, India, China (the BRICs), Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Tentative calculations put this non-DAC contribution at around 10% of global bilateral aid (ECOSOC, 2008), a substantial – and increasingly important – composition of international aid flows which has started to attract considerable attention (see Manning, 2006; Mawdsley, 2010; 2012; Paulo & Reisen, 2010; Wood, 2008).

In order to qualify for ODA, countries have to be classified as potential recipients by the OECD-DAC. The list is reviewed every three years (Fink & Redaelli, 2010: 14). Clearly, some countries receive more ODA than others, although this is dependent on how ODA flows are measured – for example, while Bangladesh received 1.4 billion USD of aid in 2004, this was equivalent to just 2% of GDP or roughly 10 USD per person. In contrast, São Tomé and Principe received 33 million USD in the same year, but this worked out as 67% of GDP or about 209 USD per person (Radelet, 2006: 5).

According to Radelet (2006: 6), ODA tends to be ‘one of the largest components of foreign capital flows to low-income countries, but not to most middle-income countries, where private capital flows are more important’. However, as he also points out, declines in aid do not necessarily correspond with increases in private capital; aggregate data can obscure the fact that increased private capital flows may be concentrated in just a small number of MICs.

ODA can target and promote specific ‘transmission channels’ or ‘mechanisms’ for growth, such as investment, imports, public sector fiscal aggregates, and government policy (Gomanee et al., 2005a). However, ODA is also used to finance, amongst other things, direct budget support (Vidal & Pillay, 2004), Sector-Wide Approaches (SWAps) (Foster, 2000), climate change mitigation efforts (Michaelowa & Michaelowa, 2005), and social protection programming (Giovannetti, 2010) such as state-run programs designed to provide non-contributory cash payments to the poor (Künnemann & Leonhard, 2008).

Moreover, different countries supply different types of aid. For example, while Indian assistance tends to consist primarily of non-monetary aid (mainly in the form of technical assistance and scholarships), China tends to offer a wider mix of monetary and non-monetary aid, the former of which is usually tied to the use of Chinese goods and services (McCormick, 2008). The OECD-DAC is reasonably clear about what counts as ODA and what does not. Any money spent on military aid, peacekeeping and counter-terrorism, for example, is not reportable as ODA.

According to Fink and Redaelli (2010: 2), humanitarian assistance ‘is meant to provide rapid assistance and distress relief to populations temporarily needing support after natural disasters, technological catastrophes, or conflicts’, and is considered a separate type of aid in accordance with its foundations in humanitarian law. Similarly, Demekas et al. (2002) argue that post-conflict aid should be split into humanitarian aid and reconstruction aid, and that analyses of aid effectiveness should deal with each separately. In practice, however, the distinction between humanitarian aid and ODA is not always clear-cut. There are rarely clear delineations marking when or where relief ends and development begins; indeed, relief and development have come to be viewed as occupying a continuum rather than distinct categories (Sollis, 1994). This makes it difficult to identify the moment when humanitarian assistance starts feeding into and shaping longer-term developmental objectives.

Definitional debates aside, ODA has been increasingly directed towards FCAS over recent years, blurring distinctions in the process. In 2008, for example, 33.2 billion USD, or 30% of global ODA flows, was channelled to FCAS (OECD, 2010). Much of this is spent with developmental objectives in mind, such as achieving progress towards the MDGs, but there has also been an increase in financing ‘ODA-related security activities’ (Oxfam, 2011). The propensity of some bilateral donors to design their aid allocation and spending patterns in accordance with national security interests (i.e. addressing the problems of FCAS in order to shore up the ‘global borderlands’) also calls into question the objectives of ODA. Additionally, there are certain caveats within the OECD definition of ODA which give rise to a further blurring of what counts as the ‘economic development and welfare of developing countries’. For example, temporary assistance to refugees from developing countries arriving in donor countries is reportable as ODA during the first 12 months of stay, as are all costs associated with repatriation (OECD, 2008).

So, there are a great many types, instruments and products of aid (see Box 1.1 for a typology and Box 1.2 for an approximate chronology of instruments below). The multiplicity of aid products matters within the context of different country classifications. For many, the fact that increasing numbers of MICs have become aid donors is a compelling argument that they should no longer qualify as aid recipients. Rostoski (2006) considers the aid relationship between Germany and China, concluding: ‘the central government in Beijing has … accumulated the necessary financial means to solve the problems [associated with poverty] in its own country without foreign assistance’ (Rostoski, 2006: 543). He insists that Germany should stop giving financial aid and concentrate instead on providing technical assistance and advice. Further, in an assessment of German aid to Namibia (an upper MIC), Amavilah (1998) stops short of calling for an end to aid, but finds that German direct foreign investment and trade seem more preferable than aid. Although German aid to Namibia is ‘clearly important’ to the country’s economic growth, even the short-term impacts are found to be small. Yet, others argue that MICs still require aid, and indeed that aid can play an important role in their continued development. For example, Jaradat (2008: 271) points out that many MICs face ‘considerable challenges’ which necessitate the continuation of aid.

Box 1.1 A typology of aid instruments

According to Ohno and Niiya (2004: 5), over the last 50 years, aid modalities have evolved in response to emerging development priorities (e.g. from capital shortages to structural reforms to government capacity building). Subsequently, today there are multiple ‘types’ of aid. A number of authors have argued for the disaggregation of aid into its various types in order to refine conceptual models and policy analysis (e.g. Mavrotas, 2005; Ouattara, 2007; Suhrke & Buckmaster, 2006). In light of the numerous instruments listed below, this certainly makes a great deal of sense. It is, of course, important to note that in practice there may be some overlap between the different types of aid (Severino & Ray, 2009: 21).

Broadly speaking, financial aid can be either concessional or non-concessional. Concessional aid refers to grants or subsidised loans (where there is a ‘grant element’ of at least 25%), while non-concessional aid refers to loans that carry market, or near market terms. Aid can also be tied, although this practice is becoming less popular. Official Development Assistance (ODA) is the most well-known form of financial aid. ODA is bound by OECD-DAC rules.

Disaggregating financial aid further, there is project aid and program aid.

Project aid can: use government systems (i.e. the donor-supported project can still be part of the government budget); use parallel systems (i.e. where the donor has taken the lead in design and appraisal); or go through NGOs/private providers.

Over the years the role of project aid has diminished and the role of program aid has increased, evolving into Sector Wide Approaches (SWAps). SWAps are government- led and require that all significant public funding for the sector supports a particular sector policy and expenditure program thus harmonizing approaches across the sector. Under this arrangement, aid often comes in the form of pooling funds. Sectoral budget support can be earmarked meaning that aid must be spent on specific expenditure categories within the sector.

There has also been a shift from structural adjustment operations, such as balance of payments support and Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), to general budget support which aims to institutionalize a new kind of aid relationship between donors and recipients. This involves new conditionality contracts which are ex-post, policy-linked, empirically based, country-specific, and more country-driven. Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) are an example of this approach, and aim to build better donor-recipient partnerships and integrate civil society more effectively into the policy process (see also the Paris Declaration principles).

Financial aid can operate at different scales or levels. It can be upstream (i.e. policy and institutions) or downstream (i.e. implementation). Aid can also be used to fund debt relief, to increase the financial resources available to the recipient government.

Non-financial aid includes food aid and technical assistance.

Humanitarian assistance can be split broadly into relief aid and reconstruction aid, although this distinction is often blurred in practice. Leader and Colenso (2005) list a number of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part IAid 1.0

- Part IIAid 2.0

- Annex

- References

- Index