- 528 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Foreign Aid and Development

About this book

Peter Hjertholm, Editorial Assistant Aid has worked in the past but can be made to work better in the future. In this important new book, leading economists and political scientists, including experienced aid practitioners, re-examine foreign aid. The evolution of development doctrine over the past fifty years is critically investigated, and conven

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Major themes

1

The evolution of the development doctrine and the role of foreign aid, 1950–2000

Erik Thorbecke

Introduction

The economic and social development of the third world, as such, was clearly not a policy objective of the colonial rulers before the Second World War. Such an objective would have been inconsistent with the underlying division of labour and trading patterns within and among colonial blocks. It was not until the end of the colonial system in the late 1940s and 1950s, and the subsequent creation of independent states, that the revolution of rising expectations could start. Thus, the end of the Second World War marked the beginning of a new regime for the less developed countries involving the evolution from symbiotic to inward-looking growth and from a dependent to a somewhat more independent relation vis-à-vis the excolonial powers. It also marked the beginning of serious interest among scholars and policymakers in studying and understanding better the development process as a basis for designing appropriate development policies and strategies. In a broad sense a conceptual development doctrine had to be built which policymakers in the newly independent countries could use as a guideline to the formulation of economic policies.

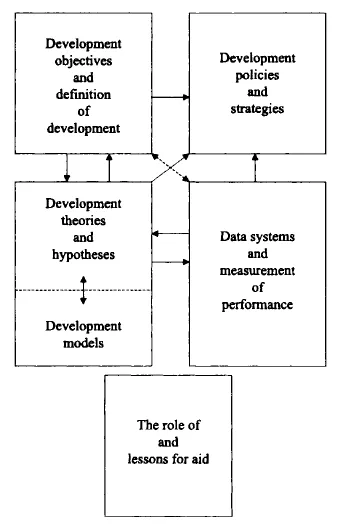

The selection and adoption of a development strategy—i.e. a set of more or less interrelated and consistent policies—depend upon three building blocks: (1) the prevailing development objectives which, in turn, are derived from the prevailing view and definition of the development process, (2) the conceptual state of the art regarding the existing body of development theories, hypotheses and models and (3) the underlying data system available to diagnose the existing situation and measure performance. Figure 1.1 illustrates the interrelationships and interdependence which exist between (i) development theories and models, (ii) objectives, (iii) data systems and the measurement of performance and (iv) development policies and strategies. These four different elements are identified in four corresponding boxes in Figure 1.1. At any point in time or for any given period these four sets of elements (or boxes) are interrelated. Thus, it can be seen from Figure 1.1 that the current state of the art, which is represented in the southwest box embracing developments theories, hypotheses and models, affects and is, in turn, affected by the prevailing development objectives—hence the two arrows in opposite directions linking these two boxes. Likewise, data systems emanate from the existing body of theories and models and are used to test prevailing development hypotheses and to derive new ones. Finally, the choice of development policies and strategies is jointly determined and influenced by the other three elements—objectives, theories and data, as the three corresponding arrows indicate.1

In turn, the role and function of foreign aid is influenced by and has to be evaluated in the light of the contemporaneous state of the art in each of these four areas. Clearly a deeper and better understanding of the process of development, based on the cumulative experiences of countries following different strategies over time, and empirical inferences derived from these experiences, helps illuminate how foreign aid can best contribute to development.

Figure 1.1 Key interrelationships between development theories, models, objectives, data systems, development policies and strategies and the role of and lessons for foreign aid.

At the same time it is evident—and is well documented in other chapters of this book—that the socioeconomic development of the aid-recipient countries is only one of the objectives of the donor countries. Political and commercial objectives play an important role in the allocation of foreign aid in the programmes of many donor countries. While recognising the role that non-developmental goals play in the allocation of aid, it would be overly cynical to dismiss altogether the developmental benefits of aid— whether they resulted directly from developmental motivation by donors or indirectly, as a side-effect of politically motivated resource transfers. Furthermore, a significant part of aid is distributed through multilateral channels and is therefore less susceptible to being influenced by strictly political considerations.

Hence, in this opening chapter we explore how the concept of foreign aid as a contributing factor to the development of the third world evolved historically within the broader framework of development theory and strategy over the course of the last five decades of the twentieth century. The analytical framework presented above and outlined in Figure 1.1 is applied to describe the state of the art that prevailed in each of these five decades and, in particular, how the conception of the role of foreign aid changed as a function of the development paradigm in vogue entering a given decade.

The application of the above framework to the situation that actually existed in each of the last five decades helps to highlight in a systematic fashion the changing conception of the development process. Such an attempt is undertaken next by contrasting the prevailing situation in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, respectively. The choice of the decade as a relevant time period is of course arbitrary and so is, to some extent, an exact determination of what should be inserted in the five boxes in Figure 1.1 for each of the five decades under consideration.2

Figures 1.2–6 attempt to identify for each decade the major elements which properly belong in the five interrelated boxes. In a certain sense it can be argued that the interrelationships among objectives, theories and models, data systems and hypotheses and strategies constitute the prevailing development doctrine for a given time period. A brief sequential discussion of the prevailing doctrine in each of the five decades provides a useful way of capturing the evolution that development theories and strategies have undergone and of the changing role of aid. A final section sums up and concludes.

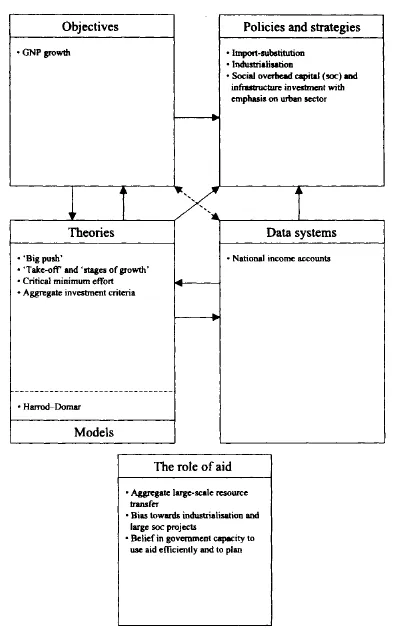

The development doctrine during the 1950s

Economic growth became the main policy objective in the newly independent less developed countries. It was widely believed that through economic growth and modernisation per se, dualism and associated income and social inequalities which reflected it would be eliminated. Other economic and social objectives were thought to be complementary to—if not resulting from—GNP growth. Clearly, the adoption of GNP growth as both the objective and yardstick of development was directly related to the conceptual state of the art in the 1950s. The major theoretical contributions which guided the development community during that decade were conceived within a one-sector, aggregate framework and emphasised the role of investment in modern activities. The development economists’ tool kit in the 1950s contained such theories and concepts as the ‘big push’ (Rosenstein-Rodan 1943), ‘balanced growth’ (Nurkse 1953), ‘take-off into sustained growth’ (Rostow 1956) and ‘critical minimum effort thesis’ (Leibenstein 1957) (see Figure 1.2).

What all of these concepts have in common, in addition to an aggregate framework, is equating growth with development and viewing growth in less developed countries as essentially a discontinuous process requiring a large and discrete injection of investment. The ‘big push’ theory emphasised the importance of economies of scale in overhead facilities and basic industries. The ‘take-off principle was based on the simple Harrod-Domar identity that in order for the growth rate of income to be higher than that of the population (so that per capita income growth is positive) a minimum threshold of the investment to GNP ratio is required given the prevailing capital—output ratio. In turn, the ‘critical minimum effect thesis’ called for a large discrete addition to investment to trigger a cumulative process within which the induced incomegrowth forces dominate induced income-depressing forces. Finally, Nurkse’s ‘balanced growth’ concept stressed the external economies inherent on the demand side in a mutually reinforcing and simultaneous expansion of a whole set of complementary production activities which combine together to increase the size of the market. It does appear, in retrospect that the emphasis on large-scale investment in the 1950s was strongly influenced by the relatively successful development model and performance of the Soviet Union between 1928 and 1940.

The same emphasis on the crucial role of investment as a prime mover of growth is found in the literature on investment criteria in the 1950s. The key contributions were (i) the ‘social marginal production’ criterion (Khan 1951 and Chenery 1953), (ii) the ‘marginal per capita investment quotient’ criterion (Galenson and Leibenstein 1955) and (iii) the ‘marginal growth contribution’ criterion (Eckstein 1957).

Figure 1.2 Key interrelationships in the 1950s.

It became fashionable to use as an analytical framework one-sector models of the Harrod-Domar type which, because of their completely aggregated and simple production functions, with only investment as an element, emphasised, at least implicitly, investment in infrastructure and industry. The one-sector, oneinput nature of these models precluded any estimation of the sectoral production effects of alternative investment allocations and of different combinations of factors since it was implicitly assumed that factors could only be combined in fixed proportions with investment. In a one-sector world GNP is maximised by pushing the investment ratio (share of investment in GNP) as high as is consistent with balance-ofpayments equilibrium. In the absence of either theoretical constructs or empirical information on the determinants of agricultural output, the tendency was to equate the modern sector with high productivity of investment, and thus direct the bulk of investment to the modern sector and to the formation of social overhead capital—usually benefiting the former.

The reliance on aggregate models was not only predetermined by the previously discussed conceptual state of the art but also by the available data system which, in the 1950s, consisted almost exclusively of national income accounts. Disaggregated information in the form of input-output tables appeared in the developing countries only in the 1960s.

The prevailing development strategy in the 1950s follows directly and logically from the previously discussed theoretical concepts. Industrialisation was conceived as the engine of growth which would pull the rest of the economy along behind it. The industrial sector was assigned the dynamic role in contrast to agriculture which was, typically, looked at as a passive sector to be ‘squeezed’ and discriminated against. More specifically, it was felt that industry, as a leading sector, would offer alternative employment opportunities to the agricultural population, would provide a growing demand for foodstuffs and raw materials, and would begin to supply industrial inputs to agriculture. The industrial sector was equated with high productivity of investment—in contrast with agriculture—and, therefore, the bulk of investment was directed to industrial activities and social overhead projects.3 To a large extent the necessary capital resources to fuel industrial growth had to be extracted from traditional agriculture.

Under this ‘industrialisation-first strategy’ the discrimination in favour of industry and against agriculture took a number of forms. First, in a large number of countries, the internal terms-of-trade were turned against agriculture through a variety of price policies which maintained food prices at an artificially low level in comparison with industrial prices. One purpose of these price policies—in addition to extracting resources from agriculture —was to provide cheap food to the urban workers and thereby tilt the income distribution in their favour. Other discriminatory measures used were a minimal allocation of public resources (for both capital and current expenditures) to agriculture and a lack of encouragement given to the promotion of rural institutions and rural off-farm activities. In some of the larger developing countries, such as India and Pakistan, the availability of food aid on very easy terms—mainly under us Public Law 480— was an additional element which helped maintain low relative agricultural prices.4

A major means of fostering industrialisation, at the outset of the development process, was through import substitution—particularly of consumer goods and consumer durables. With very few exceptions the whole gamut of import substitution policies, ranging from restrictive licensing systems, high protective tariffs and multiple exchange rates to various fiscal devices, sprang up and spread rapidly in developing countries. This inward-looking approach to industrial growth led to the fostering of a number of highly inefficient industries.

It should not be inferred that the emphasis on investing in the urban modern sector in import-substituting production activities and physical infrastructure was undesirable from all standpoints. This process did help start industrial development and contributed to the growth of the modern sector. It may even, in some cases, have provided temporary relief to the balance-of-payments constraint. However, by discriminating against exports —actual and potential—the long-run effects of import substitution on the balance-of-payments may well turn out to have been negative.

Role of foreign aid

The main economic rationale of foreign aid in the 1950s was to provide the necessary capital resource transfer to allow developing countries to achieve a high enough savings rate to propel them into selfsustained growth. The role of aid was seen principally as a source of capital to trigger economic growth through higher investment. Households in poor countries—hovering around the subsistence level—were seen to face the almost impossible task of raising their savings rates to a level sufficient to generate sustained growth rates. As Ruttan (1996) pointed out, in most cases developing areas lacked the physical and human capital to attract private investment so that there did not appear to be any alternative to foreign aid as a source of capital.

Two other interrelated factors made aid attractive as an instrument of growth: first, the faith that governments could plan successfully at the macro level as evidenced by the large number of five-year plans formulated during this period and, second, the simplicity of the Harrod-Domar model to calculate the amount of foreign aid required to achieve a target growth rate. In retrospect it was this totally aggregate planning framework and the focus on industrialisation-first that led to the neglect of the agricultural sector.

In any case, whatever the development rationale of aid in the 1950s, it was clearly already subservient to security objectives in the aid programmes of the us and probably Western Europe. The us aid was intended as a weapon to address the security threat of spreading communism (Ruttan 1996:70).

The development doctrine during the 1960s

Figure 1.3 captures the major elements of the development doctrine prevailing in the 1960s. On the conceptual front the decade of the 1960s was dominated by an analytical framework based on economic dualism. Whereas the development doctrine of the 1950s implicitly recognised the existence of the backward part of the economy complementing the modern sector, it lacked the dualistic framework to explain the reciprocal roles of the two sectors in the development process. The naive two-sector models following Lewis (1954) continued to assign to subsistence agriculture an essentially passive role as a potential source of ‘unlimited labour’ and ‘agricultural surplus’ for the modern sector. It assumed that farmers could be released from subsistence agriculture in large numbers without a consequent reduction in agricultural output while simultaneously carrying their own bundles of food (i.e. capital) on their backs or at least having access to it.

As the dual-economy models became more sophisticated, the interdependence between the functions that the modern industrial and backward agricultural sectors must perform during the growth process was increasingly recognised (Fei and Ranis 1964). The backward sector had to release resources for the industrial sector, which in turn had to be capable of absorbing them. However, neither the release of resources nor the absorption of resources, by and of themselves, were sufficient for economic development to take place. Recognition of this active interdependence was a large step forward from the naive industrialisation-first prescription because the above conceptual framework no longer identified either sector as leading or lagging.

A gradual shift of emphasis took place regarding the role of agriculture in development. Rather than considering subsistence agriculture as a passive sector whose resources had to be squeezed in order to fuel the growth of industry and to some extent modern agriculture, it started to become apparent in the second half of the 1960s ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Tables

- Figures

- Contributors

- Acronyms and abbreviations

- Preface

- Foreign aid and development

- Part I: Major themes

- Part II: Aid instruments

- Part III: Economic perspectives on aid design

- Part IV: Broader issues

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Foreign Aid and Development by Finn Tarp in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.