- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Popular Italian Cinema

About this book

Exciting new critical perspectives on popular Italian cinema including melodrama, poliziesco, the mondo film, the sex comedy, missionary cinema and the musical. The book interrogates the very meaning of popular cinema in Italy to give a sense of its complexity and specificity in Italian cinema, from early to contemporary cinema.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Popular Italian Cinema by L. Bayman, S. Rigoletto, L. Bayman,S. Rigoletto in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Fair and the Museum: Framing the Popular

Popular Italian cinema encompasses many delights: the foundational spectacle of the early historical epics and the passionate theatricality of the first screen divas take their place within a gallery of emotional and sensual pleasures. Even the canonical works of Italy’s post-war art cinema grew from the soil of popular genres and were nourished by traditions of theatricality and entertainment. And yet while Pasolini, Fellini, Visconti and Antonioni are icons of the European auteur canon and neorealism is a core unit of academic study, the vast and diverse output that made cinema a key popular form in Italy remains in many ways more unfamiliar. This volume aims to help correct this imbalance of attention by exploring films that may count in one way or another as popular entertainment. It interrogates the very meaning of the popular and hopes to give a sense of its complexity and specificity in Italian cinema.

The volume seeks to probe the intellectual value of the popular pleasures mentioned above, and to lead further. To analyse popularity means to consider the relation of Italian cinema to other forms of art, entertainment and habits of everyday existence – and to record some of the tangled battles between radicalism and Fascism, Marx and God, or art and commerce, in which the popular has been called to fight. In view of this, the volume interrogates the popular not only for the joys and controversies it engenders, but as a key aspect of cultural life. This chapter lays out some of the analytical frameworks from which to see it as such. It also takes into account the ways in which popular Italian cinema has come to be defined and understood by means of its distinctive relation with its audiences (actual or imagined). As a whole, this volume seeks to shed light on this relation and some of the problems that it has traditionally raised in Italy.

Industrial aspects of popularity

Cinema entered Italian life as a technological marvel, a novelty exhibited by entrepreneurs1 principally in the popular arena of public fairs.2 Thus it was born amidst a profusion of spectacle, popular narratives and stage shows (many of which cinema absorbed and pushed towards obsolescence or the second rank), as it was across much of the rest of the industrialized world. In Italy, this general framework is inflected by a domestic heritage which includes the circus, opera, dramatizations of songs (sceneggiate) and, as noted by early film theorist Riciotto Canudo, the tradition of Roman pantomime (Mosconi, 2006a: 48). Avenues for further research into cinema’s position within popular life include the importance of Sicilian puppet theatres and non-entertainment practices such as Catholic church services. The reliance on music and a stylized and emphatic expressivity in these determining cultural practices is of more than merely historical importance, as it marks the popular more generally in Italian cinema and can be traced to the emergence of cinema in a land of lower penetration of the standardized national language than France, America and Britain (see De Mauro, 1996).

The Italian film industry was established by the 1910s on the success of historical epics and diva films, with comedies and serials also playing an important role (see Lottini, in this volume). Following its collapse in the 1920s, concerted efforts were made under Fascism to revive the industry through intense use of the traditionally popular formulae of theatre and romance. Film culture of this period was also consolidated by emulating and adapting the style of the Hollywood films that were the most popular in Italy during the 1920s. This emulation was, however, modified by national specificities promoted, amongst others, by Fascist film authorities aiming to combat Hollywood’s foreign influence: glamour and ordinariness, the excitement of urban life and consumerism, or the myth of the land and rural romance conveyed Fascist Italy’s new desire to ‘acquire a modern and slightly cosmopolitan image as well as to recuperate (and reinforce) traditional […] values’ (Hay, 1987: 10).

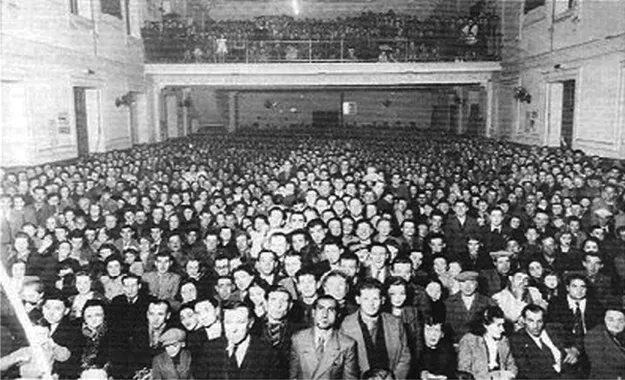

As part of Fascist interventions into the industry, the Direzione Generale per la Cinematografia was instituted within the Ministry of Popular Culture. Its main goal was to foster the Italian film industry’s nation-making capacities and international reputation. The circulation of films was facilitated through an increasingly direct relationship with social and political institutions such as the OND (Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro), a state agency whose main aim was the organization of national leisure time. By 1938, the OND had 767 cinemas under its supervision whilst also managing a fleet of ‘cinema wagons’ that showed commercial films as well as government newsreels across Italy’s regions. The screenings took place outdooors, ‘making the experience itself an emblem of direct access and communality.’ (Hay, 1987: 15)

The popularity of cinema in Italy has been partly the result of a very competitive film industry, but this was never more so than from the 1950s to the 1970s (a period to which many of the chapters below address themselves). Although the Second World War had a devastating effect, the industry’s recovery was comprehensive. In 1949, Italian films made only 17.3 per cent of box office receipts. By 1953, they had gone up to 38.2 per cent; in 1960 to 50 per cent; in 1971 to 65 per cent (Quaglietti, 1980: 289). Italians became the most frequent attenders at cinemas in Europe: in 1955, Italy had 10,570 screens, compared to the 5688 in France and 4483 in the United Kingdom; in 1977, in Italy the screens were 10,587, whilst in France they were 4448 and in the United Kingdom 1510. In 1965, 513 million Italians went to watch films; in that same year, France had 259 million cinema-goers and the United Kingdom had 326 million (Corsi, 2001: 124–5). This was also a period in which the film industry had a remarkable significance for Italy’s economy. In 1954, cinema constituted almost one per cent of total national income and employed 0.5 per cent of the working population. In Rome, in particular, cinema was the second largest industry after the construction industry (Wagstaff, 1995: 97).

Figure 1.1 A crowded screening at the Cinema Adua, Turin (1941)

During this period of growth, an extraordinary number of skilled technicians, talented producers and writers developed, and became absorbed into, the production of films based on popular formulae. These filoni, a category which is distinguished from genre by the much shorter timescale in which they exist, found great popularity both abroad and in Italy, making the 1950s to the 1970s a period in which the Italian domestic market was partly wooed away from American films. The domestic market also flourished thanks to the expansion of cinemas in the provinces and in the working-class metropolitan neigh-bourhoods where most of the popular genre films made in Italy were being shown. As Christopher Wagstaff (1992) has noted, Italy in this period became an exporter of popular genre films to a greater degree than ever. The international circulation of prestigious neorealist exports was first eclipsed – in box-office terms – by mythological epics such as the sword-and-sandal film and then the Spaghetti Westerns. In 1946, no Italian film was imported into the United Kingdom, but by 1960 the United Kingdom had become a significant importer of popular Italian adventure formula films for its B-movie market. South America and the Middle East also became important export markets, all of which complicates the extent to which Italian popular cinema was for Italians (see Wagstaff, this volume).

Various trends coalesced in the mid-1970s to bring an end to this industrial pre-eminence: notably, the partial removal of protectionist measures, state subsidies and support to the industry; the withdrawal of much American money and the move by Hollywood to saturation-selling of blockbusters; and increasing competition from television. The decline in the industry was stark:

From 1975 to 1985, the number of moviegoers decreased by almost 400 million. In the 1990s, that number dropped to below 100 million tickets sold annually. By 1985, the number of working screens dropped from 6,500 to 3,400 and by the year 2000, that number fell to 2,400. While 230 films were produced in 1975, only 80 were made in 1985.

(Brunetta, 2009: 256)

The production, exhibition and export of popular films remains the staple of the Italian industry, although one which, following the war, is much reduced compared to the first three decades of the century (for a discussion of contemporary cinema, see Galt, and O’Leary, both in this volume).

Popular utopia

Popularity in the cinema is judged only in its most empirical form by box-office numbers and production figures. What is striking is how often the transformation of public life wrought by the popularity of cinema is thought of as signalling a route to utopia; and not only in the opportunities allowed entrepreneurs for fast, vast riches. Experiments in the early days of the feature film in structuring utopia into film spectatorship informed the creation of the politeama, ‘a special theatre all’italiana […] attended by a socially heterogeneous public, and representing an undifferentiated space par excellence […] Its architectural variety can be connected to the expressive variety of the show’ (Mosconi, 2006a: 133).3 Although these theatres became obsolete, the offer of universality and community remains central to marketing the film experience, both of indivual films and of cinemagoing as a general practice. Analysis of interwar film posters, for example, shows how the promised experience is one that: ‘enables an escape from reality together with the feeling of being part of a collective, which turns, unmistakeably, into a public’ (Mosconi, 2006a: 262).4

Cinema’s place in public life became, from the 1910s onwards, an issue of national political importance. The King attended the fortieth anniversary celebration of cinema in 1935, an event promoted by a Mussolini impressed by cinema’s ‘character of universality’ (1928, cited in Brunetta 2000a: 34).5 The matter of cinema’s popularity did not pass unremarked upon by God’s representatives on Earth, Pope Pius XI decreeing that ‘the cinema occupies a place amongst modern entertainments of universal importance [… and] of the most popular form of entertainment in times of leisure, not just for the rich but for all classes of society’ (1936, cited in Mosconi, 2006a: 249).6 It is notions of universality and popularity, of the utopian possibilities enabled by the technology of cinema and the collective aspect of its spectatorship, that feed into post-war neorealist hopes for cinema as a tool for popular emancipation.

Ways of thinking that insist on universality can also be linked to the Vatican’s catholic ambitions. As well as this they are rooted in the reality of a country which at least until the boom of the 1960s was felt as having only partially advanced towards the industrialized modernity which gives rise to a differentiated working-class culture. Taking the idea of the power of cinema further, frequently across its history the allure of the silver screen has evoked a sense that, for the popular masses, cinema contains something magical (whether for good or otherwise). In a country only newly adapting to mass society from the conditions of semi-feudal agriculture, cinema is seen as creating ‘a new kind of regular ritual’ (Brunetta, 2000a: 39),7 the cinema theatre, according to Pius XII the ‘church of the modern man in the big cities’ (1943, cited in Mosconi, 2006a: 270–1).8 The much-repeated reports of hysteria and worship that greeted the early divas contribute to a perception of cinema as able to create new behaviour and identity at a mass level. Models of spectatorship that grant cinema near-mystical powers to induce conformity have left their traces – often problematically – not only on official mistrust of the form, but on discussion of the ideological effects of popular cinema, which will be discussed further below.

The uses of popularity

The idea of a mass audience unified in a non-rational public experience has engendered much official desire to harness the imputed power of cinema. This desire is felt first of all in an aspiration towards artistic quality (emerging from anxiety over the lack of cultural legitimacy of a popularly comprehensible entertainment born in the trave...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Fair and the Museum: Framing the Popular

- 2 Italian Cinema, Popular?

- 3 The Prettiness of Italian Cinema

- 4 The Pervasiveness of Song in Italian Cinema

- 5 Melodrama as Seriousness

- 6 Moving Masculinity: Incest Narratives in Italian Sex Comedies

- 7 Laughter and the Popular in Lina Wertmüller’s

- 8 Strategies of Tension: Towards a Reinterpretation of Enzo G. Castellari’s The Big Racket and The Italian Crime Film

- 9 ‘Il delirio del lungo metraggio’: Cinema as Mass Phenomenon in Early Twentieth-Century Italian Cinema

- 10 Dressing the Part: ‘Made in Italy’ Goes to the Movies with Lucia Bosé in Chronicle of a Love Affair

- 11 Hercules versus Hercules: Variation and Continuation in Two Generations of Heroic Masculinity

- 12 On the Complexity of the Cinepanettone

- 13 Cinema and Popular Preaching: the Italian Missionary Film and Fiamme

- 14 Dolce e Selvaggio: The Italian Mondo Documentary Film

- Index