![]()

Part I

Culture, Identity and Everyday Life

![]()

1

Narratives of European Identity

Monica Sassatelli

Introduction1

The Euro-crisis that began in 2010 has shown that, ultimately, legitimation for European integration is sought in a ‘common identity’ and consequent solidarity: in public discourse, bailouts and confidence-boosting packages are presented as possible, sufficient or justifiable in as much as they are intended to benefit the common good of the EU as a whole, and therefore assume a common identity, that could then be organized and represented in ways comparable to the national one. To critics, the on-going crisis is final proof that such an identity is lacking. So, precisely now that the public debate is full of economic and political analysis and ‘hard’ data and arguments, the relevance of soft, cultural aspects of ‘being European’ has never been more crucial. Understanding identity remains central – in Europe as elsewhere – because no matter how flawed the concept might appear (see Brubaker and Cooper 2000 for an oft-cited critique), it remains a politically diffuse category, as well as a ‘practical’ or ‘lay’ one. Notably it is one that may remain ‘unflagged’ in everyday situations, but is invoked in times of crisis.

My long-standing interest in European identity stems from a wider preoccupation with ‘cultural identity’ in general. I found in the developing EU institutions and their role in contemporary Europe a perfect case to problematize and question notions of cultural identity, which at the national level – the accepted, therefore often normative, model – were based on homogeneity and indeed homology between a people, a place/nation and a culture. Approaching European identity as a cultural identity embodied in specific narratives – public, academic, institutional – allows us to consider the several ‘Europes’ that are at stake, to distinguish them analytically and to trace the possibilities and constraints that they suggest. European identity is a perfect case also because, more explicitly than other identities, it is very much still in the process of being made and is still heavily contested – partly because so many different agencies are trying to shape it, including of course scholars, but also, more powerfully, European institutions.

This chapter will address the development and current interpretations of narratives of European identity, with a particular focus on institutional frameworks – that is those produced and supported by the two key organizations that call themselves European, the Council of Europe (COE) and the European Union (EU). The argument is that contemporary Europe is a good example of both the possibilities and the dangers of narratives of identity, as well as a useful point of comparison for other identity narratives, in particular national ones. What follows is first an outline of the dominant institutional narrative of European identity. I will then compare this to both the actual process of European integration and to scholarly reflection on European identity, which often have a much wider frame of reference. While there are several narratives of Europe, there are also several performances of those narratives or scripts. An important dimension of the analysis that follows therefore concerns how this institutional European narrative is interpreted, or put into practice by those meant as its recipients. In particular, I will look at the local implementation of specific cultural policy initiatives relevant to identity-building. By way of example, I then briefly report on my case study of the European City/Capital of Culture initiative.

As such, my chapter does not deal directly with film and television. It does, however, provide a context in which debates about film and television and their relationship to narratives of European identity can be developed. It also examines some of the key terms at play in the development of European cultural policy, terms that also impact upon the development of a more specific European audiovisual policy.

Building Europe: institutional narratives

What are the dominant institutional narratives of Europe available today? As many have observed, and as clearly emerges from official documents, the main current institutional narrative is the one expressed succinctly in the European Union’s motto, ‘united in diversity’. Identity-building technologies developed by the nation state are still in the hands of nation states (education systems, the media, but also welfare systems and military service). Self-proclaimed European institutions therefore have to be very cautious in their search for a story to tell. Because of the need to incorporate and build on the perceived diversity of nations and to accommodate multiple allegiances, and because imagining the Community (or Union) is a process taking place in a public sphere that has become suspicious of such projects, especially so at the European level, those institutions have elaborated a complex rhetoric that is synthesized in the formula of ‘unity in diversity’.

This solution finds a counterpart in current academic definitions of identity and resonates with the political(ly correct) spirit of the age, looking for viable ways to combine difference with equality (Touraine 1997). It also resonates with conceptualizations of the European dimension as a mediating instance between global and local allegiances (Lenoble and Dewandre 1992). These are no longer seen as opposite phenomena, but as expressions of the complexity of the modern world, in which different layers of identification constitute what is commonly called the multiple identity of the contemporary subject, with the important specification that this is recognized not only at the individual level, but also in its impact on collective allegiances. The academic literature on European identity is now vast, but in recent years influential voices have tried to reformulate, via Europe, the very notion of identity, perhaps most famously building on Derrida’s vision of Europe’s specificity as constituted by its others (Derrida 1991; see also Derrida and Habermas 2003).Whilst this may still not fit the bill of ‘strong’ models of identity (Kantner 2006), as Rosi Braidotti has noted, ‘[r]ecently, wise old men like Habermas and Derrida along with progressive spirits like Balibar have taken the lead, stressing the advantages of de-centring Europe as a sociopolitical laboratory so as to develop a post-nationalist sense of citizenship’ (Braidotti 2006: 80). The argument goes that as the myth of national cultural homogeneity is exposed, the crisis that ensues also means the possibility of an alternative vision of identity that ‘requires the desire, ability and courage to sustain multiple belongings in a context that predominantly celebrates and rewards unified identities’ (2006: 85). For Braidotti, this is about European identity ‘becoming-minoritarian’ and ‘nomadic’.

These are the challenges that face those trying to shape a narrative of European identity. The simplified official rhetoric may seem a far cry from these highly theoretical visions. Indeed, when enshrined in official discourse, the formula of ‘unity in diversity’ has attracted more critique than praise, with many analysts viewing it as a formal solution with no substance, but also as a thinly veiled renewal of Eurocentric triumphalism (Shore 2000). Its clearer statement and consolidation in official EU discourse, following in the steps of the COE (Sassatelli 2009, Ch. 1), was introduced with the Maastricht Treaty on the European Union, in the section introducing competence on culture at EU level. This is aimed at promoting ‘the flowering of the cultures of the member States, while respecting their national and regional diversity and at the same time bringing the common cultural heritage to the fore’ (CEC 1992, title IX, Article 128).2 Rather than simply dismissing this as either anodyne or dangerous rhetoric as the majority of critics does, what is interesting about the concept of ‘unity in diversity’ is both that it keeps alive two competing narratives, one focusing on ‘unity’ and the other on ‘diversity’, and that it is a reflexive narrative constantly including itself, and criticisms of it, in the story being told.

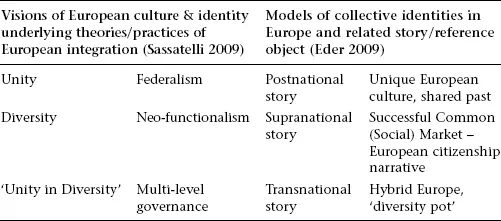

While stories of European unity/diversity/unity-in-diversity draw from narrative elements that go well beyond contemporary institutional European integration in terms of time and space, and conceptually, it is also possible to see parallel developments with recent theories and practices of European integration. This perspective also helps to make sense and reduce the apparent haphazard multiplicity of histories of Europe. To show this, in reviewing notions of ‘European cultural identity’ I have proposed a tripartite model. Although originally elaborated over a decade ago (Sassatelli 2002), it still resonates with more recent models, such as the one put forward in Klaus Eder’s (2009) influential article on how to theorize European identity. I have included a schematic representation of both models in Table 1.1.

My point of departure is that, although maybe unspoken, a vision of what Europe is, in terms of its culture or identity, is at the heart of integration theories and practices, even those which apparently speak only of markets, quotas and the like. In fact, even if Jean Monnet, one of the founding fathers and key strategists of the EU’s economic and technical integration, never said ‘If we were to start again, we would start from culture’, this apocryphal aphorism still holds a secure place in the literature and does indeed capture a perceived necessity to re-launch the EU project more in tune with aspirations that were there from the beginning, even if never fully and openly admitted (Banus 2002). After all, even Monnet envisaged in his Memoires ‘a new breed of man ... being born in the institutions of Luxembourg, as though in a laboratory’, proposing that ‘it was the European spirit which was the fruit of common labour’ (cited in Bellier 1997: 441).

Table 1.1 Models of European identity

As I indicate in the table above, the notions of what is essentially European that are implicit in the two established rival models of European integration, federalism and neo-functionalism, as well as in the recent critique of both, show a correspondence with different approaches to European cultural identity. Thus the idea of the unity of Europe as a culture and identity resonates with federalist claims, while approaches that emphasize the plurality or diversity of European culture and identity are more in tune with ‘technical’, neofunctionalist claims. The third approach, which tries to find unity in diversity is similar in style to so-called multi-level governance claims, emerges out of the impasses of the previous two and, as we have seen, is the dominant approach today.

In a similar vein, Eder looks for the dominant ‘story’ being told about contemporary Europe and identifies both a ‘reference object’3 around which each story pivots and the model of collective identity being represented. Whilst Eder’s point of view is different from mine, looking ‘not at political or cultural symbols but at stories that emerge in the making of a network of social relations among those living in Europe’ (Eder 2009: 433), he too identifies three main ‘stories’, each of which in different ways goes beyond the national tool-kit for identity-building. There is a postnational story emphasizing the shared memory of a murderous past as a basis for strong identification, a more pragmatic supranational story based on the idea of a successful economic and political project enshrined in the narrative of European citizenship, and finally a yet to be consolidated but increasingly relevant transnational story ‘that relates to Europe as an experiment in hybrid collective identities, not as “melting pot” but as a “diversity pot”, which is a story in the making’ (ibid.). Whilst I do have some issues with Eder’s notion of collective identity, which are beyond the scope of this chapter,4 what is interesting is not only how the two models overlap, but most importantly that in both, the third type (unity in diversity, hybrid Europe) is of a different kind from the previous two, and at the same time, by being a form of ‘reflexive storytelling ... increasingly used for hybrid constructions’ (ibid.: 441) it contains them. It is in other words a ‘story of stories’: it does not assume a core substance defining Europe anymore, but focuses on the story of ‘the art of living together’, which turns itself reflexively into the object of a story.

Despite the amount of energy that has been devoted to the elaboration and study of a narrative of European identity, some of the main questions remain open. Is diversity something to ‘deal with’ – as implied in the diffuse idea that many narratives are equal to no story – in the sense of mitigating, alleviating or tolerating diversity, in narrative terms as well as in concrete social terms? Are the homogenizing forces of globalization – but is this the only direction? – necessarily in competition with the effort to ‘preserve’ identities that are specific and therefore particularistic? And is there still a clearly identifiable and corresponding distinction between the cosmopolitanism of elites and the localism of people (Castells 1997), which clearly places European narratives on the intellectualized, elite side of the spectrum, speaking only to the brain and not to the heart? Is this especially the case when narratives emanate from the EU, a technocratic project pushed too far too fast, as the current economic and political crisis encourages many observers to argue?

I will certainly not provide exhaustive answers to all these fundamental questions; however, from the perspective presented here, some indicators as to likely outcomes and the range of possibilities open to actors in the field can be sought in how this institutional narrative of ‘unity in diversity’ informs actual initiatives and policies and, in this way, is appropriated by a wider set of actors. This means looking, as a particularly significant example, at the cultural policies initiated by European institutions. Although initiatives under this umbrella are many and diverse, they have a similar style: they mainly stimulate local, direct action, bestowing t...