- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

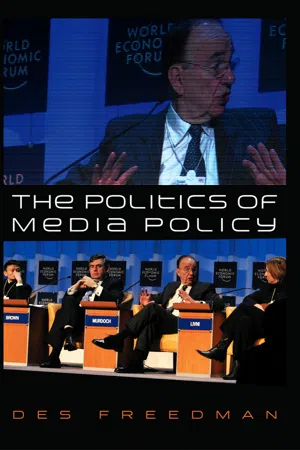

The Politics of Media Policy

About this book

The Politics of Media Policy provides a critical perspective on the dynamics of media policy in the US and UK and offers a comprehensive guide to some of the major points of debate in the media today. While many policymakers boast of the openness and pluralism of their media systems, this book exposes the commitment to market principles that saturates the media policy environment and distorts the development and application of democratic media policies.

Based on interviews with dozens of politicians, regulators, special advisers, lobbyists and campaigners, The Politics of Media Policy considers how governments, civil servants and media corporations have shaped the drawing up of rules concerning a range of issues including:

- Media ownership

- Media content

- Public broadcasting

- Digital television

- Copyright

- Trade agreements affecting the media industries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Politics of Media Policy by Des Freedman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introducing Media Policy

Is Policy Political?

Media systems do not emerge spontaneously from the logic of communication technologies, or from the business plans of media corporations, or from the imaginations of creative individuals. The thesis of this book is that media systems are instead purposefully created, their characters shaped by competing political interests that seek to inscribe their own values and objectives on the possibilities facilitated by a complex combination of technological, economic and social factors. There is, therefore, little that is inevitable about the ‘shape’ of the media in a particular country or region – whether it is largely commercial or state-controlled; whether it is open or resistant to technological change; whether it is critical or complacent in terms of its social role. In other words, there is nothing predetermined about the personality of the media systems to which we are exposed. While the form a media system assumes at any one time is by no means the direct expression of a state’s political priorities, it makes little sense to ignore the impact of political actors and political values on the character of the wider media environment. Media policy, the systematic attempt to foster certain types of media structure and behaviour and to suppress alternative modes of structure and behaviour, is a deeply political phemonenon.

This is not a widely accepted assertion. For many participants and commentators, media policy – like many other areas of public policy – refers to a disinterested process where problems are solved in the interest of the public through the impartial application of specific mechanisms to changing situations. Policymaking, in this view, is a rather technical procedure where policy changes emerge in response to, for example, technological developments that necessitate a re-formulation of current approaches and a new way of ‘doing things’. Consider the introduction by the former British Secretary of State for Culture, Tessa Jowell, to what became the 2003 Communications Act: ‘The infrastructure of the future needs fast, efficient and affordable communications – telecommunications, the internet and broadcasting. It requires the best competitive environment, effective regulation and continued public and private investment in the technologies of the future’ (HoC Debates, 3 December 2002: col. 782 – emphasis added). Policy is therefore developed in a situation in which, because of irrepressible external forces, there is no alternative but to introduce new legislation or forms of regulation if desirable social or economic objectives are to be pursued.

This mechanical notion of policy creation often marginalizes politics and political agency in favour of administrative technique and scientific principles. This was most famously expressed by Harold Lasswell’s conception of a ‘policy science’ where ‘ “policy” is free of many of the undesirable connotations clustered around the word political, which is often implied to mean partisanship or corruption’ (Lasswell 2003 [1951]: 88). Policy development and implementation work best when they are executed in an informed but impartial manner that makes use of ‘scrupulous objectivity and maximum technical ingenuity’ (2003: 103). Such ideals remain relevant today. When asked about the principles that underpin his approach to implementing media policy, the head of one of the bureaux of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) who deals daily with highly controversial matters concerning ownership and diversity, responded that policy application is a value-free and non-subjective process:

Key principles – gee! You make it sound like this is some sort of philosophical inquiry here. As dry as it may sound, what we do is we have a governing statute that we try to implement, we have a series of bureau decisions over the year, sometimes in adjudicatory proceedings and sometimes in rulemakings that have set forth an established regulatory framework, and our job at the bureau level is really just implementing that statutory and regulatory framework. So it’s not like we sit around and think big thoughts, about what is in some metaphysical sense good and evil, right and wrong. You know, Congress directs us to do things and we do our best to effectuate that.

‘Effectuating’ congressional will therefore requires the participation of groups of economists, technologists, legal specialists and government experts who are best able to safeguard the scientific and non-partisan nature of policymaking. Policy, according to this perspective, is the domain of small thoughts, bureaucratic tidiness and administrative effectiveness.

Another reading of Lasswell’s work suggests that, far from trying to deny the political imbrications of policy, he was keenly aware that politics constitutes a key context in which policy ideas are developed and rolled out. The task is not to avoid politics per se but the subjective and irrational manner of what passes for much contemporary political discourse. ‘Policy science’, according to Robert Hoppe (1999: 204), ‘was not a technocratic strategy in order to substitute politics with enlightened administration … For Lasswell policy science was a vital element in a political strategy to maintain democracy and human dignity in a post-World War II world.’ Indeed, Lasswell called for a ‘policy frame of reference’ that ‘makes it necessary to take into account the entire context of significant events (past, present and prospective) in which the scientist is living’ (Lasswell 2003: 103). A sensitivity to political problems and aspirations is an essential part of the policy scientist’s toolkit.

This book shares Lasswell’s belief that policy is part of a strategy to attain specific political goals, and shares even many of his ‘value goals’ that underpin the definition of what can be considered a problem (if not his solutions to these problems). According to Lasswell, the term ‘value’ refers to ‘ “a category of preferred events,” such as peace rather than war, high levels of productive employment rather than mass unemployment, democracy rather than despotism, and congenial and productive personalities rather than destructive ones’ (2003: 95). Policy practice is a decisive arena in which different political preferences are celebrated, contested or compromised. This is far from the mechanical or administrative picture that is often painted, whereby faceless civil servants draft legislation on the advice of ‘experts’ and ‘scientists’, in the interests of a ‘public’ and at the behest of a ‘responsible’ government. ‘Governing’, argues Hal Colebatch (1998: 8), ‘does not just happen: it is constructed out of an array of shared ideas, categories, practices and organizational forms. “Policy” is a way of labeling thoughts about the way the world is and the way it might be.’ Policymaking can be seen as a battleground in which contrasting political positions fight both for material advantage, for example legislation that is favourable to particular economic or political interests, and for ideological legitimation, a situation in which certain ideas are normalized and others problematized.

This struggle occurs throughout the policy process, from the definition of the policy ‘problem’ through the selection of a ‘solution’ to the eventual distribution of that ‘solution’. ‘How a policy issue area is identified is political’, argues Sandra Braman (2004: 154), ‘because it determines who participates in decision-making, the rhetorical frames and operational definitions used, and the resources – and goals – considered pertinent.’ Every step of the way is marked by fierce competition for, or deployment of, resources, influence and power. This is a conflict that has been theorized in radically different ways by, for example, pluralists who maintain that this struggle is ultimately fair and productive, and more critical voices who argue that there is a profoundly unequal playing field in which talk of fair competition and open bargaining is misplaced and idealized (see chapter 2). Either way, Nicholas Garnham is surely right to assert that media policymaking ‘is not and can never be the tidy creation of ideal situations. Compromises and trade-offs are endemic’ (Garnham 1998: 210).

This book aims to consider selected media policy developments in the light of these claims that (a) policymaking is a political act and (b) that it is marked by conflict. It focuses on the underlying assumptions and ideas that define policy ‘problems’, shape policy debates and guide policy objectives. The policy process is both structured – circumscribed by institutional, economic, technological and governmental dynamics – and actor-driven in the pursuit of different norms and goals. The book aims, in particular, to emphasize the importance of political agency in the media policy process. This is not to idealize media policymaking as a battle solely between rival individuals and their different beliefs but to suggest, as Thomas Streeter does in his account of broadcast deregulation in the United States, that ‘ideas do matter’ (1996: xii). The current system of commercial broadcasting in the USA exists not because it is intrinsically better than other systems or because it is somehow natural, but ‘because our politicians, bureaucrats, judges and business managers, with varying degrees of explicitness and in a particular social and historical context, have used and continue to use the power of governments and law to make it exist’ (1996: xii). Streeter argues, against those who see politics as marginal to the contemporary policy process, that a highly political concept – corporate liberalism – underpins the policy vision and regulatory behaviour of those who designed, and now sustain, the rules that surround the US broadcast environment.

This book builds on the framework of those theorists like Streeter who have sought to incorporate both agency and structure into their accounts of media policy and who see the policy process as driven by ideology as much as technology or economics. Peter Humphreys attributes the deregulatory transformations in European broadcasting to the ‘paradigmatic change’ (1996: 299) in the 1980s where pro-market ideas became increasingly hegemonic. Robert Horwitz argues that telecommunications deregulation in the USA in the same decade was due to an ‘ideologically diverse regulatory reform coalition’ (1989: 6) of social liberals and free-market conservatives, both of these being elements that identified existing regulatory structures as inefficient and undemocratic. Reflecting on the UK, Goodwin (1998) and Freedman (2003a) identify the historical contradictions of Conservative and Labour politics respectively as central to the direction of British television policies. More recently, Chakravartty and Sarikakis (2006) and Raboy (2002) focus on capitalist globalization as the key influence on contemporary media policy; Galperin (2004) and Hart (2004) prioritize the institutional dynamics and political legacies that have decisively shaped the development of digital broadcasting; while McChesney (2000) and Hesmondhalgh (2005) assert that neo-liberal ideas are a source of inspiration for media policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic.

The intention of this book is to consider a range of contemporary media policy debates in the context of two competing political perspectives: first, through a pluralist account stressing the extent to which media policies are based on wide-ranging, informed and open debates and are aimed at maximizing the democratic, cultural and economic value of the media; and, second, through critiques of the policy process that identify the unequal power relations involved and the lopsided policy objectives that favour business and political elites, hallmarks of a neo-liberal political-economic order that has emerged since the 1980s. Both perspectives focus on the conflicted nature of the policy process, although the former argues that consensus is usually reached after the expression of different positions while the latter insists that such differences cannot be resolved in a just manner as long as access to resources and influence remains so uneven. Given existing levels of social inequality and the rising anger at political and media elites, an assessment is made of the wider implications of pluralist and critical accounts in terms of their ability to help the reader describe, evaluate and intervene in the direction of politics today.

The Need for Media Policy

Media as a Key Economic Sector

Media policy is public policy that responds to the distinctive characteristics of, and unique problems posed by, mass-mediated communications. First, of course, the media are significant economic entities responsible for an increasing amount of domestic and world trade. Figures that account for the specific value of the media are hard to come by and are notoriously unreliable – media, for example, are often counted as part of the ‘copyright industries’ in the USA and the ‘creative industries’ in the UK. Nevertheless, it is estimated that the ‘core’ copyright industries – films, television, home video, DVDs, business and entertainment software, books and music – account for approximately 6.5 per cent of US gross domestic product (GDP), some $819 billion, and employ over five million workers (Siwek 2006: 2, 4). These copyright industries now account for $110 billion in export activity, overshadowing that of motor vehicles ($76 billion), aircraft ($50 billion), food ($48 billion) and pharmaceuticals ($26 billion) (Siwek 2006: 5). The UK’s ‘creative industries’ – as above but with the inclusion of fashion, architecture and design – account for at least £53 billion or 8 per cent of GDP and are one of the fastest-growing sectors, increasing by around 6 per cent since 1997 (Patent Office et al. 2005: 1). Media policies concerning the ‘copyright’ and ‘creative’ industries are therefore vital components of both domestic and supranational industrial policy.

Media as Agents of Social Reproduction

Policy initiatives are also justified by the argument that media products are not ordinary commodities but systems and networks endowed with special political and cultural significance: that the symbolic transactions facilitated through the media play a key role in the production and reproduction of social relations. Borrowing from Lasswell’s transmission model of mass communication, Nicholas Garnham argues the media are decisive agencies of social communication that play a constitutive, not passive, role in the process of social formation. ‘Who can say what, in what form, to whom, for what purposes, and with what effect will be in part determined by and in part determine the structure of economic, political and cultural power in a society’ (Garnham 2000: 4). The struggles to own and control media outlets, to have a range of perspectives aired, to have access to media technologies and to have the right to answer back – in other words, the struggle to talk to and be heard by others on a mass scale – shape not just individual identities but the broader networks of power in which we circulate. Tessa Jowell, in the same introduction to communications legislation that she described as economically necessary, makes this same point that:

communications is about much more than economics. The Bill deals with the means by which our society speaks to itself. And, as it were, hears the echo. It is the means by which we talk to the world. It is a shaper of our culture, our identity and our values. (HoC Debates, 3 December 2002: col. 782)

This is an illustration of what Thompson (1995) and Silverstone (2005) refer to as the process of mediation: the rude intervention of the media into our everyday frameworks for making sense of the world. Mediation, argues Silverstone (2005: 189), ‘requires us to understand how processes of communication change the social and cultural environments that support them as well as the relationships that participants, both individual and institutional, have to that environment and to each other’. Media are no longer extraneous to spheres of political action, personal identity and cultural belonging but become intimate participants in the way in which we experience these environments and how they are framed. The manoeuvres of politics, the legitimation of war, the conduct of business, the pursuit of fame, the celebration of identity, the search for friends and the naming of enemies are all, to one extent or another, subject to the play of media power. It is hardly surprising then that, in an increasingly mediated world, media systems should be subjected to forms of intervention, surveillance and control that befit their status as crucial agents of social meaning.

This has led to the highlighting of policy objectives that focus, in particular, on the fostering (and protection) of media forms that are seen to play a central role in the exercise of democracy and the involvement of citizens in the formal political process. In a liberal democracy, citizens require free and unfettered access to information and a full range of views if they are to make informed judgements about issues in the public sphere. This is one of the guiding principles of recent media legislation and regulation in the USA and the UK. For example, in a recent review of US broadcast ownership rules:

the FCC strongly confirmed its core value of limiting broadcast ownership to promote viewpoint diversity. The FCC stated that ‘the widest possible dissemination of information from diverse, and antagonistic sources, is essential to the welfare of the public.’ The FCC said multiple independent media owners are needed to ensure a robust exchange of news, information and ideas among Americans. (FCC 2003a: 2)

The British government makes similar claims about the significance of the media:

The functioning of democracy depends on the availability of a range of independent sources of information, views and opinions … Given the democratic importance of the media, we are concerned to see that diversity of opinion and expression is actually maintained and increased. Therefore we may continue to need backstop powers to underpin plurality of ownership and a plurality of views in the media. (DTI/DCMS 2000: 36)

The extent to which both American and British governments have actually fulfilled these commitments to diversity and plurality is rather dubious and will be examined in the chapters that follow. Nevertheless, it is the case that policy interventions are justified in the light of their stated desire to maximize the provision of different voices and perspectives in and through the media.

Media and ‘Market Failure’

There is, however, another justification for intervention: that precisely because the media play such a crucial public role, there are particular economic characteristics of media goods that, if uncorrected in a capitalist market, may lead to the under-serving of audiences and further jeopardize the democratic functions the media are assumed to have. Many theorists have written about what they describe as the ‘market failure’ (Collins and Murroni 1996; Congdon et al. 1995; Graham and Davies 1997; Leys 2001) that arises from the very nature of the media industries. Garnham identifies three specific problems (2000: 55–62):

- Media markets tend towards concentration because of the economies of scale and scope that are used by corporations to offset the unpredictability of public taste and their resulting need for novelty and innovation. This is a situation that tends to favour large organizations that are able to offer a menu of choices and to cross-promote their offerings and therefore to spread risk throughout their portfolios.

- Media products are largely ‘public goods’ in that the viewing of, for example, a television programme does not compromise someone else’s consumption of that programme (unlike eating an apple where one person’s consumption of an apple prevents someone else from eating the same apple). This non-rivalrous characteristic of the media commodity means that corporations are forced to devise strategies, such as copyright, advertising and box office mechanisms, that transform public into private ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface

- 1 Introducing Media Policy

- 2 Pluralism, Neo-liberalism and Media Policy

- 3 The Reinterpretation of Media Policy Principles

- 4 Dynamics of the Media Policymaking Process

- 5 Media Ownership Policies

- 6 Media Content Policies

- 7 The Disciplining of Public Broadcasting

- 8 The Politics of Digital

- 9 Britain and America in the World

- 10 Conclusion

- References

- Index