eBook - ePub

The Un/Making of Latina/o Citizenship

Culture, Politics, and Aesthetics

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Un/Making of Latina/o Citizenship

Culture, Politics, and Aesthetics

About this book

Examining a wide range of source material including popular culture, literature, photography, television, and visual art, this collection of essays sheds light on the misrepresentations of Latina/os in the mass media.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Un/Making of Latina/o Citizenship by E. Hernández, E. Rodriguez y Gibson, E. Hernández,E. Rodriguez y Gibson,Kenneth A. Loparo,Eliza Rodriguez y Gibson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Dyad or Dialectic? Deconstructing Chicana/Latina Identity Politics*

Alicia Gaspar de Alba

As part of his intervention at the 1993 Whitney Biennial, Chicano installation Chicano artist Daniel Martínez used the medium of the museum visitor’s button to play with the viewer’s awareness of identity politics. The phrase “I can’t imagine ever wanting to be white,” was fragmented onto the buttons that visitors were required to wear throughout their visit to the museum. Most buttons had only one or a few words of the phrase written on them, and a few had the entire phrase. Let’s perform a little deconstructive magic on that phrase:

I = the artist’s subjectivity, the artist’s sense of self, his I/eye-dentity

can’t imagine = negation of the imaginary

ever wanting = a subjunctive exposition of desire

to be = an existential dilemma

white = the privileged other

In loftier, theoretical jargon, that phrase might be rewritten as: Chicano subjectivity negates the imaginary existential desire to be privileged. Or, invoking Albert Memmi, I cannot imagine a world where the colonized other does not desire to be the same as the colonizer. As the vast majority of the Whitney’s visitors are white and/or privileged, the irony of wearing a button that denied the desirability of whiteness was, I speculate, either lost on the audience, or, it provoked an enormous discomfiture—both actually positions of privilege.1 “Why would someone not want to be white,” one museum visitor actually asked his companion aloud as he clipped his button to his lapel. Did Caliban in Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” ever desire to be the same as Prospero? Or, did he curse Prospero for occupying and appropriating his native land, for forcing the colonizer’s tongue down his colonized throat? Worse than the absence of desire to be white, perhaps, is the inability to imagine being white. Framed within this discourse of whiteness and the recognition/negation of privilege, viewers entered the show already ideologically predisposed to question their own identity politics as well as those of Daniel Martinez and the other artists in the show.

The term “identity politics,” which came to dominate the scholarship of ethnic studies, cultural studies, and gender/sexuality studies in the 1980s and 1990s, and has only recently started gaining currency as a legitimate theory and praxis of qualitative analysis in the hard sciences and the social sciences, is an interesting term.2 Very few of us realize how interesting until we look up the word “identity” in a decent dictionary. There we find that the word comes from identical, which means same as. “The state or fact of remaining the same. The condition of being oneself or itself and not another. The sense of self.” Identity, then, is the perception of oneself that is the same as something else, a self-definition that is the same as that which is not other; thus, identity implies both sameness and difference. If we contextualize the word identity within postmodern discourses of multiculturalism and diversity, we find that identity largely connotes difference rather than sameness. Indeed, to study difference implies to study identities that are not only different from the normative white, male, middle-class, and heterosexual identity that constitutes the “universal,” but also always in flux and differently constituted by cultural, historical, and/or political context. One example of this fluctuating signifier of identity is what Rafael Pérez-Torres calls “situational identity” (Pérez-Torres 1997), a sense of self that changes depending on the situation, such that the same individual may be, for example, Chicana at home, Latina in the media, Hispanic in a grant application, and American in a passport.

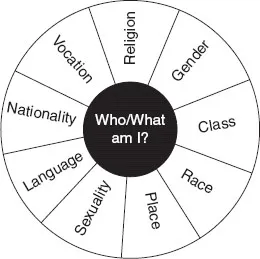

The politics of identity, then, asks a simultaneous contradiction: “who am I the same as?” and “how am I different?” It is the exploration of this contradiction and of the tensions that exist between these opposite questions that I most enjoy teaching my Chicana/o Studies students how to do, and for that purpose, I have created an interactive heuristic called the Identity Wheel to illustrate and simplify this interaction of identity/difference in the process of self-construction (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The Identity Wheel

The Identity Wheel is composed of a hub—the I/eye-dentity of the self, represented by the question “who/what am I?” Out of that central question radiate spokes of difference that signify identity variables that inform the core subjectivity. These spokes of difference both anchor and move that subjectivity, both answer and confuse the central question. It is neither a linear nor a sequential process, but one that encompasses mobility and stability, clarity and contradiction. Neither movement nor stasis is possible, however, without the outer rim that holds the spokes and the hub together. Moreover, that outer rim, I argue, turning on all of those axes of difference joined at the fulcrum of identity, is subjectivity. The wheel itself could also be a representation of Kimberle Crenshaw’s notion of intersectionality, showing the different registers of experience that intersect our lives and inform our identities. Rather than seeing this intersectionality as a collision of differences, however, the Identity Wheel provides a more holistic analysis.

How do we know something different? By what cognitive functions do we recognize difference? The question at the center of the Identity Wheel is not just engaging the comparative function, “who/what am I the same as?” but also, the analytical and deconstructive, “how is the other the same as I, and how am I different from others who are like me?” Answering these secondary questions presupposes an ability to discern dissonance and resonance, to interpret and internalize their contradictory meanings without having to choose between them. Gloria Anzaldúa described this as “divergent thinking, characterized by movement away from set patterns and goals and toward a more whole perspective, one that includes rather than excludes” (Anzaldúa 2012, 101). From divergent thinking comes the ability to both tolerate and sustain contradictions, and to imagine new/other identities—the quintessential skills of mestiza consciousness.

The new mestiza copes by developing a tolerance for contradictions, a tolerance for ambiguity. She learns to be an Indian in Mexican culture, to be Mexican from an Anglo point of view. She learns to juggle cultures. She has a plural personality, she operates in a pluralistic mode—nothing is thrust out, the good the bad and the ugly, nothing rejected, nothing abandoned. Not only does she sustain contradictions, she turns the ambivalence into something else. (Anzaldúa 2012, 101)

I have no doubt that divergent thinking is an intrinsic talent of bilingual and bicultural people of all stripes, but to what degree is the Anzaldúan notion of mestiza consciousness a factor of the Latino/a mind? Do Latinas/os share the same process of identification and historical empowerment through their own indigenous mestizaje as Chicanas/os? We might share two linguistic roots—English and Spanish—occupied histories, and cultural contradictions, but what role does the “Indian” race play in Latino/a subjectivity?

Let me pause here to compare the identity politics of the labels Chicana and Latina—two terms that are often conflated but whose very conflation I want to interrogate by applying the Identity Wheel heuristic to each one. Since the Identity Wheel applies to individuals with subjectivity, let me represent each identity label with its corresponding individual who will serve as an embodiment for each label: the Nuyorican actress/performer/fashion designer, Jennifer López (or Jenny from the Bronx), for the label, Latina, and the Tejana singer/performer/fashion designer, Selena, for Chicana. In “Jennifer as Selena: Rethinking Latinidad in Media and Popular Culture,” Frances Aparicio calls the conflation of these two performers the “Jennifer López/Selena dyad” (Aparicio 2003, 103). By comparing these two transnational icons, I will show how the J-Lo/Selena dyad that Aparicio writes about is, in fact, a representation of the Chicana/Latina dialectic.

Dyad or Dialectic?

The way some people “find religion,” I found Selena the day she died. Not that I didn’t already know who she was; what kind of Tejana would I be if I didn’t own at least three of her CDs and couldn’t dance to the norteño tracks of “Como La Flor” and the cumbia rhythms of “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom”? It’s just that the day she died, the day she became “Saint Selena” as Ilans Stavans calls her, was the day I discovered the mythic significance of this iconic corpus and sacrificial redeemer, healer, and miracle-worker of the borderlands in the popular Chicano/a imagination.3 It wasn’t until I watched the broadcast of J-Lo’s concert in San Juan and saw those thousands of Puerto Riqueños/as in the audience crying and singing along to “I Could Fall in Love” that I truly understood the transborder power of Selena, whose star burns as brightly in the flag of Puerto Rico as it does in the flag of Texas—both conquered territories of the imperializing nineteenth-century United States, although not coequally appropriated into the national narrative.

For Aparicio, Jennifer López and Selena come together in one representational body not to homogenize “the Latina” experience—as so many have criticized—but to, in fact, embody the very cultural, linguistic, and racial affinities, the historical realities of colonialism, mestizaje, linguistic terrorism, cultural schizophrenia, territorial displacement, and organic feminism that connect not just the bodies of these two women, but Chicanas and Latinas at large. On the back of Jennifer López, Selena indeed becomes una puente de Latinidad, as Aparicio suggests. Selena—the performer, the myth, and the icon—can be read as a bridge that metaphysically (through her myth and her music) and physically (through the body of Jennifer López playing the title role of Gregory Nava’s film, Selena) connects Chicano/a and Latino/a cultural identities.

But here is my departure from Aparicio’s discussion, and actually, not so much a departure as a detour or perhaps a pit stop on this crazed freeway of identity politics that demands our daily commute through its labyrinths of solitude and disjuncture. Aparicio writes that

[T]he case of Jennifer López performing—and being transformed into—Selena for the film by Gregory Nava brings forth certain dynamics of identification and disidentification, among two women, one Tejana singer, Selena, and Jennifer López, a Nuyorican from the Bronx. This, in turn, suggests how both Jennifer López and Selena, as US Latinas (an identity constructed through their audiences, the industry, and the content of their work, but also through the history of ethno-racialization), have shared similar historical experiences as colonized subjects. (Aparicio 2003, 94)

Even though she attributes their conflation as Latina bodies to popular culture and history, Aparicio appears to have no quarrel with the assumption that J-Lo and Selena are both US Latinas. Indeed, part of her argument for the new conceptualization she offers for the term Latinidad, is based on Emma Pérez’s construction of a decolonial “third space,” which, in Aparicio’s view, could encompass the historical experiences of both a Nuyorican from the Bronx and a Chicana from south Texas, as well as their individually and mutually colonized subjectivities. In other words, Aparicio’s take on Pérez’s “third space” is this over-arching concept of Latinidad. My question is: are these identities interchangeable? If Chicanas can be Latinas, can Latinas be Chicanas? Given the affinities named above and articulated in more detail in Aparicio, it would seem that the terms are, if not interchangeable, then certainly parallel enough to fit under the same umbrella. The trouble with affinities, however, is that they are not really parallel, and not necessarily equal in referent value. When James Clifford writes about the affinities between tribal and modern art in an exhibition at MOMA, he is clearly privileging modern art as the subject and using tribal art as the object of comparison, which is reflected in modern art.4

In the case of the terms Chicana and Latina, which one is the subject/referent and which one is the object/reflection? It has become politically correct, not to mention culturally expedient, to fit Chicanas under the broader rubric of Latinidad, but is the equation reversible? Can Latinas fit under the Chicana umbrella? For some this would be a rhetorical question, but I employ it here to suggest that the term Latina, when used as a signifier for Chicana experience, privileges the Latina subject. Chicana becomes a disidentified reflection of Latina. We have grown accustomed to the social assumption that Chicanas are another type of Latina, but since the shoe doesn’t fit on the other foot, the term Latina becomes, in effect a top-down construction, similar to the Hispanic label imposed by the United States Census in the 1980s, precisely the kind of homogenizing movida that Aparicio critiques. Thus, while we could say that Selena can be as Latina as J-Lo, and indeed, she is a pan-Latina/o celebrity, it doesn’t work the other way around. J-Lo could never be a Chicana unless she is enacting a Chicana role, as she did in Selena and in two other Gregory Nava films, Mi Familia and Bordertown5, and as she did on the stage in San Juan when she performed Selena during her concert.6 It’s important to recognize the difference between identity, or sense of self, and performance of identity, or becoming/representing another self.

Rather than subsuming one identity under the other or umbilically connecting them under the “broader,” more hegemonic or homogenizing term for an ethnicity based on a shared linguistic root, we must pull them apart first and deconstruct their differences before we attempt to “explore our (post)colonial analogies” (Aparicio 2003, 94). In the rest of this piece, I will focus on Selena, but will return to this notion of postcolonial analogies later.

Selena’s Pompas (with Nods to “Jennifer’s Butt”7)

Joe Nick Patoski’s Selena: Como la Flor (1996), the first full-scale biography of this icon and hero of Chicano/a popular culture, tells the sweet and tragic story of Selena Quintanilla’s rise to fame and popularity, her short-lived glory at the pinnacle of the American Dream, and her catastrophic death and ensuing commodification soon thereafter. Divided into nine chapters, Patoski’s book provides a chronological narrative that traces Selena’s life from her birth in Lake Jackson, Texas to her funeral in Corpus Christi and her posthumous ascendancy as a cultural icon.

We see Selena in the 1970s as a happy, bubbly little girl who loved school and played at having a band with her brother and sister. We follow the Chicano Partridge Family’s quest for celebrity status in the 1980s when Selena was still billed Selena y los Dinos and was singing at benefits, weddings, school dances, tardeadas and concert halls in the Southwest and in México. We track the nascent glory of Selena’s success as a Tejano, Mexican, and American music star in the ear...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Dyad or Dialectic? Deconstructing Chicana/Latina Identity Politics

- Chapter 2 Drag Racing the Neoliberal Circuit: Latina/o Camp and the Contingencies of Resistance

- Chapter 3 Decolonial New Mexican@ Travels: Music, Weaving, Melancholia, and Redemption Or, “This is Where the Peasants Rise Up!”

- Chapter 4 The Importance of the Heart in Chicana Artistry: Aesthetic Struggle, Aisthesis, “Freedom”

- Chapter 5 The Political Implications of Playing Hopefully: A Negotiation of the Present and the Utopic in Queer Theory and Latina Literature

- Chapter 6 Cherríe Moraga’s Changing Consciousness of Solidarity

- Chapter 7 Revolutionary Love: Bridging Differential Terrains of Empire

- Chapter 8 The Postmodern Mo(nu)ment: An Analysis of Citizenship, Representation, and Monuments in Three Acts

- Chapter 9 Sucking Vulnerability: Neoliberalism, the Chupacabras, and the Post-Cold War Years

- Chapter 10 Pictures of Resistance: Recasting Labor and Immigration in the Global City

- List of Contributors

- Index

- Erratum to: Sucking Vulnerability: Neoliberalism, the Chupacabras, and the Post-Cold War Years