![]()

1

Theoretical Foundations of International Entrepreneurship

International entrepreneurship began emerging as a field of research in the late 1980s with the aim to understand the phenomenon of international new ventures and born global firms, i.e., firms that internationalize early on from inception. Over time, the field has progressively enlarged, extending its scope and positioning at the intersection of entrepreneurship and international business (McDougall‐Covin, Jones and Serapio, 2014). This enlargement raised increased academic interest in the topic and a growing amount of contributions dedicated to special issues in leading journals (e.g., Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 38, Issue 1, 2014), as well as the Journal of International Business Studies decade award to Oviatt and McDougall the for their 1994 contribution, and to Knight and Cavusgil for their 2004 article.

On the other hand, this growing body of literature is still rather fragmented and – according to some authors – lacks unifying paradigms and theories (Keupp and Gassman, 2009; Jones et al., 2011), methodologies (Coviello and Jones, 2004), and even has gaps (Rialp, Rialp and Knight, 2015). Above all, an holistic and interdisciplinary approach to research in international entrepreneurship is still needed (Dana, Hetemad and Wright, 1999). At the same time, it is also true that these calls for unifying theoretical frameworks and approaches in international entrepreneurship may be the result of the normal process of development of scientific disciplines (Jones, Coviello and Tang, 2011).

Our analysis of the field begins with the review of the definitions of IE suggested by different authors, we then propose a review of the typologies of international entrepreneurial organizations (IEOs) and analyse the drivers of international entrepreneurship.

1.1 International entrepreneurship and international entrepreneurial organizations

Morrow (1988) introduced the term “international entrepreneurship” in describing the evolving technological and cultural international environment that was opening previously untapped foreign markets to new ventures.

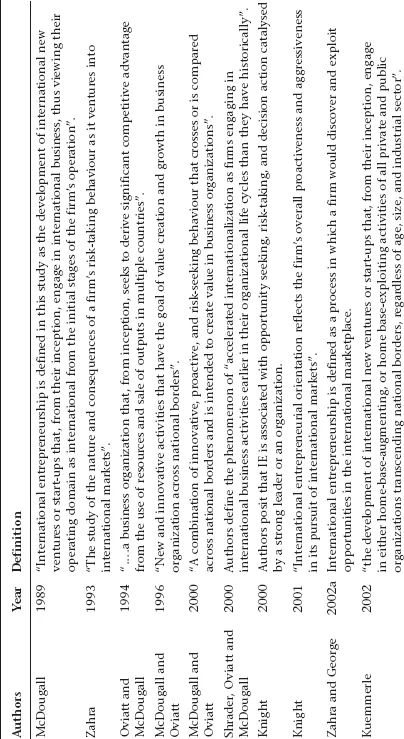

One of the first empirical studies in the international entrepreneurship area was McDougall’s (1989) work on new ventures’ international sales. This study has provided important insights into the differences between these firms and those ventures that did not start out on an international scale. McDougall (1989, p. 388) defined international entrepreneurship “as the development of international new ventures or start-ups that, from their inception, engage in international business, thus viewing their operating domain as international from the initial stages of the firm’s operation”.

In the early 1990s, Oviatt and McDougall further developed the study on the so-called “international new ventures” defined as “ ... a business organization that, from inception, seeks to derive significant competitive advantage from the use of resources and sale of outputs in multiple countries” (1994, p. 49).

The definition of the boundaries of international entrepreneurship has been discussed by many researchers: while some authors identify its domain in new ventures, others emphasize the construct of entrepreneurial behaviour, which can be observed in very different kinds of organizations. Zahra (1993, p. 9), for example, suggested that the study of international entrepreneurship should encompass both new and established firms, defining international entrepreneurship as “the study of the nature and consequences of a firm’s risk-taking behaviour as it ventures into international markets”. Wright and Ricks (1994) suggested that international entrepreneurship is observable at the organizational behaviour level and focuses on the relationship between businesses and the international environments in which they operate. Also other authors recognize that a firm’s business environment plays an important role in influencing the expression of entrepreneurial activities (Zahra 1991, 1993) and their returns (Zahra and Covin, 1995). The importance of national cultures as “loci” for different expressions of international entrepreneurship and the specific influence of the business environment emphasize the need for comparative studies as one of the areas of interest in international entrepreneurship.

In 2000 McDougall and Oviatt introduced a broader definition of international entrepreneurship including the study of established firms and the recognition of comparative (cross-national) analysis. They defined this field as “a combination of innovative, proactive, and risk-seeking behaviour that crosses or is compared across national borders and is intended to create value in business organizations” (McDougall and Oviatt 2000, p. 903). This definition considers Miller’s (1983) version of entrepreneurship as a phenomenon at the organizational level, that focuses on innovation, risk-taking, and proactive behaviour. It also focuses on the entrepreneurial behaviour of these firms rather than studying only the characteristics and intentions of the individual entrepreneurs. In a behavioural perspective, Covin and Slevin (1991, p. 7) posit that “the domain of entrepreneurship is no longer restricted in a conceptual sense to the independent new venture creation process”, and that it is possible to identify entrepreneurial organizations that are characterized by proactivity, innovativeness, and risk-taking propensity. Also Knight (2000, p. 14) stresses that international entrepreneurship is “associated with opportunity seeking, risk-taking, and decision action catalysed by a strong leader or an organisation”.

The key dimensions of entrepreneurship – innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk propensity – can thus be found and developed at the organizational level too. Innovativeness reflects a tendency to support new ideas, experimentation, and new processes, while proactiveness refers to the capacity to anticipate and act on future needs and desires. Lastly, risk-seeking conduct regards the will to commit resources, fully aware that the potential for failure may be high.

Including established firms in the analysis of international entrepreneurship permits the assumption that these type of firms can also be innovative and risk-taking. In fact, a number of well-established firms foster innovation, support venturing, and are willing to take risks.

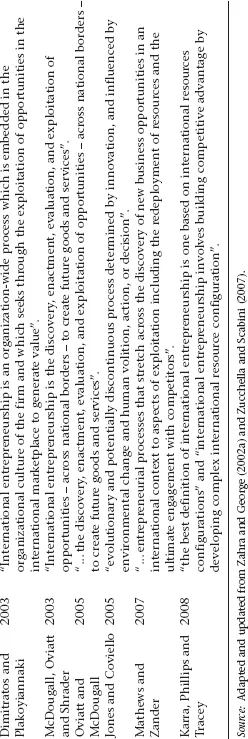

According to McDougal, Oviatt and Shrader’s (2003) definition, international entrepreneurship is “ ... the discovery, enactment, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities across national borders to create future goods and services”. Discovery and exploitation of opportunities as key characters of international entrepreneurship are also found in Zahra and George’s (2002a) understanding of international entrepreneurship as a process in which a firm would discover and exploit opportunities in the international marketplace, as well as in Dimitratos and Plakoyiannaki’s (2003, p. 189) definition of international entrepreneurship as “ ... an organization-wide process which is embedded in the organizational culture of the firm and which seeks through the exploitation of opportunities in the international marketplace to generate value”. Knight (2001, p. 159) describes international entrepreneurship as focusing on the entrepreneurial orientation of the firm, arguing that “international entrepreneurial orientation reflects the firm’s overall proactiveness and aggressiveness in its pursuit of international markets”. The process supporting international entrepreneurial orientation is described by Shane (2000) as a process of discovery, and it seems to correspond to what Weick (1995) describes as enactment.

Following Zahra and George’s (2002a) process perspective of international entrepreneurship, Jones and Coviello (2005, p. 289) posit that it is an “ ... evolutionary and potentially discontinuous process determined by innovation, and influenced by environmental change and human volition, action, or decision”. This definition highlights other important aspects of international entrepreneurship. It is a process that, over time, is influenced by environmental dynamism and hostility, which can be coped with by entrepreneurial proactive behaviour, i.e., volitional decision making and innovation. Moreover, the process shall not necessarily follow linear paths: it can be discontinuous and characterized by entrepreneurial innovation, volition, and change, all factors that determine the international development and performance of the firm.

The process view of international entrepreneurship is confirmed in Mathews and Zander (2007, p. 389) who argue that “ ... entrepreneurial processes that stretch across the discovery of new business opportunities in an international context to aspects of exploitation including the redeployment of resources and the ultimate engagement with competitors”. This definition stresses other aspects of international entrepreneurship, highlighting its dynamic character – the authors write in fact about international entrepreneurial dynamics (IED). The firm owns dynamic capabilities that it uses to reconfigure actual resources into novel combinations in order to exploit opportunities. Hence, international entrepreneurship is characterized by the ability to deploy resources to exploit those opportunities. In the process of exploiting a business opportunity, the firm must deal with competitors, which results in different “entry points and pathways of resource deployment [ ... ] and should ultimately result in superior business practices” (ibid., p. 397). The focus on resource deployment and reconfiguration is also found in Karra, Phillips and Tracey (2008) according to which “the best definition of IE [international entrepreneurship] is one based on international resources configurations” and that “IE involves building competitive advantage by developing complex international resource configuration” (p. 442). The process of exploitation of opportunities from inception onwards is also stressed by Kuemmerle (2002, p. 105) who argues that international entrepreneurship concerns “the development of INVs [international new ventures] or start-ups that, from their inception, engage in either home-base-augmenting, or home base-exploiting activities of all private and public organizations transcending national borders, regardless of age, size, and industrial sector”.

Recently, Rialp et al. (2015) have argued that the most updated, well accepted definition of international entrepreneurship is that by Oviatt and McDougall (2005, p. 540): “ ... the discovery, enactment, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities – across national borders – to create future goods and services”. According to the authors, this definition examines and compares – how, by whom, and with what effects those opportunities are pursued and exploited across national borders, fostering both international opportunity (Mainela, Puhakka and Servais, 2014) and international entrepreneurial orientation (Covin and Miller, 2014) as key constructs that applies to all firm sizes and ages. This definition of international entrepreneurship is adopted in this book. The analysis of the definitions (collected in Table 1.1) permits to observe the mentioned gradual enlargement of the research field in terms of the object of analysis and discloses a perspective, which considers:

•both events and processes;

•both individual and organizational resources and capabilities;

•entrepreneurial attitude and orientation;

•international opportunity discovery, enactment, and exploitation;

•a context dominated by uncertainty.

The evolution in the definitions of international entrepreneurship suggests that the field is increasingly viewed as a process: we can in fact observe a shift from a static (the creation act) to a dynamic perspective (the entrepreneurial process). This perspective is discussed in Jones and Coviello (2005) process view of entrepreneurship and in Mathews and Zander (2007)’s IED. It then suggests that international entrepreneurship is not in itself a novel orientation of firms and entrepreneurs. Schumpeter (1934) underlined the entry in new markets – also in geographic terms – as an expression of entrepreneurship. The latter is not represented by the entry per se in a foreign market, rather it is a combination of behaviours at the individual and organizational level (proactiveness, innovativeness, and risk-seeking) and of actions over time, along an evolutionary and potentially discontinuous process.

Table 1.1 Some international entrepreneurship definitions

The international entrepreneurship field over time has also expanded towards the development of comparative studies (comparative internationalization entrepreneurship, CIE from now onwards). The latter are concerned with comparing entrepreneurial internationalization across countries, mostly within the same industry (Jones et al., 2011). Firm-related studies are the majority of the CIE literature (Terjesen, Hessels and Li, 2013), focusing either on characteristics, or outcomes of entrepreneurial firms. At the same time, this literature is still highly fragmented with substantial knowledge gaps related to content, theory, and methodology (ibid.).

The enlarging field of research in international entrepreneurship leads us to adopt the term IEOs (Zucchella and Scabini, 2007; Zucchella 2010), where the key characterizing features are (1) international entrepreneurial orientation and (2) international opportunity exploration and exploitation. These attributes qualify entrepreneurial organizations and represent the foundations of their behaviour. The shift in studies towards organizational behaviour is crucial to theory development because “behaviour is, by definition, overt, and demonstrable. Knowing the behavioural manifestations of entrepreneurship, we can reliably, verifiably and objectively measure the entrepreneurial level of the firm” (Covin and Slevin, 1991, p. 8).

The areas of academic study, which mainly provide theoretical arguments to international entrepreneurship, are international business, entrepreneurship, and strategic management studies. The following three chapters of the book are devoted to the understanding of how these areas of research interact and contribute to the field of international entrepreneurship.

Figure 1.1 schematizes the three core issues in international entrepreneurship according to the above definitions and to the main contributions in this field. They are represented by the three Os: (international entrepreneurial) orientation, opportunities (exploration and exploitation), (international entrepreneurial) organizations. They are consistent with the perspective of this book, which is primarily focusing on the organizational (firm-level) dimension of international entrepreneurship. The three Os will be discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Figure 1.1 Framing organizations into international entrepreneurship: the triple O (orientation, opportunities, and organizations)

Source: Own elaboration.

1.2 Entrepreneurial orientation and international entrepreneurial orientation

Entrepreneurial orientation is considered one of the constructs at the core of international entrepreneurship. This is acknowledged in the literature (cfr. Rialp et al., 2015; Weerawardena, Mort, Liesch and Knight, 2007), but at the same time it has also gained importance as a per se phenomenon of research leading to a number of literature reviews and studies (Covin and Lumpkin, 2011).

What does it mean for a firm to be entrepreneurial? Entrepreneurial orientation is not always consistently defined within the literature (Covin and Miller, 2014). It is incorporated in the McDougall and Oviatt (2000, p. 903) definition of international entrepreneurship as “ ... a combination of innovative, proactive and risk-seeking behaviour that crosses national borders and is intended to create value in organizations”, highlighting th...