- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Providing a colorful insight into the people at the forefront of the emergent Sharing Economy, a movement predicted to already be worth around $26B a year, this book gives vital advice to anyone thinking of starting or investing in a collaborative consumption business. The first of its kind, written by an author on the forefront of this new trend.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Business of Sharing by Alex Stephany in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter 1

Architects

Building on New Ground

The bay glittered in the hot morning sun and the seagulls wheeled above me. I was waiting in line for my ferry at San Francisco’s grand Ferry Building. As weekend shoppers browsed the organic farmers’ market, I was nervously planning out my lunch appointment with Lisa Gansky across the bay.

Gansky is a successful entrepreneur with two exits behind her. In 1993, she co-founded Global Network Navigator, the first website offering clickable ads, which she sold to AOL. Her second business, Ofoto, a photo-sharing service, was almost as pioneering. She grew Ofoto to over 50 million users before selling it to Eastman Kodak in 2001. I had read in Fast Company that Gansky had made “tens of millions” from her exits.

Now it seemed like she had set out to save the world through sharing. Among her many angel investments in the sharing economy are RelayRides, which lets people rent each other’s cars, Scoot Networks, a Zipcar for scooters, and Science Exchange, a website for researchers to book experiments at shared laboratories. But I was there to talk to Gansky about her visionary book, The Mesh: Why the Future of Business is Sharing. She was meeting me off the ferry in Vallejo at midday, presumably in some kind of electric Batmobile. I was at the ferry building 45 minutes early. Missing the ferry was not an option.

Better safe than sorry, I checked with the guy in front of me that I was in the right queue for Vallejo.

“Vallejo?” he blurted. “That’s the ferry for Vallejo.”

I followed his gaze. A white ferry was pulling away from the pier. “No!” I cried involuntarily.

People gathered round to assist the distressed foreigner. The next ferry to Vallejo was not until the late afternoon, long past my slot with Gansky. I had flown from London and this was a meeting I had to make. I felt sick.

“Try and catch it at Pier 41,” suggested someone. “It’s picking up folks there.”

According to Google Maps, Pier 41 was 31 minutes’ walk. I had 14 minutes and neither Lyft nor Uber could save me: the seafront road was gridlocked with traffic. So I ran. 1.5 miles down the Embarcadero. I arrived at Pier 41, sweat pouring off me. I charged up to an official stood in front of a gangplank beneath a sign that read “SAUSALITO.”

“Vallejo?” I panted.

He nodded at another white ferry in front of us, pulling away from its moorings.

“I NEED TO GET ON THAT BOAT!” I yelled.

“Sorry. I took the sign down.”

“PLEASE! I’VE JUST RUN…”

The growl of the ferry’s engines cut out. It drifted away a few more meters before slowly re-docking. They must have spotted me.

“I ain’t never seen that before,” murmured the man. “Must be your lucky day.”

He unchained the gates and I ran down the gangplank, throbbing with gratitude. They slammed the ferry doors and, as the engines powered back up, I dragged myself onto the sundeck. Soon, San Francisco’s sparkling skyscrapers and the vast spans of the Bay Bridge were disappearing into the cloudless sky. We passed Alcatraz Island. The former prison was hunched on its rock, an unrepentant hulk of concrete. The thought of those who suffered inside in solitary confinement sent a shiver down my spine. I had never felt freer. I had never felt more thankful to be part of a connected and collaborative world.

Definitions: so what is the sharing economy?

I went to a geeky school. I was taught that if you wanted to understand something the answer could be found in the many heavy volumes of the Oxford English Dictionary in the school library. Find that word or that concept in the Oxford English Dictionary and you would find the end of the scotch tape (or “Sellotape,” as we Brits call it). But the OED does not have a definition of the sharing economy. These days, I go to Wikipedia for my definitions. Indeed, the Wikipedia project itself, radically participatory and iterative, is to the sluggish centralized authority of the OED what the sharing economy is to the old economy. At least for now, Wikipedia defines the sharing economy as:

A sustainable economic system built around the sharing of human and physical assets. It includes the shared creation, production, distribution, trade and consumption of goods and services by different people and organizations. These systems take a variety of forms but all leverage information technology to empower individuals, corporations, non-profits and government with information that enables the distribution, sharing and reuse of excess capacity in goods and services.

I define the sharing economy more abruptly:

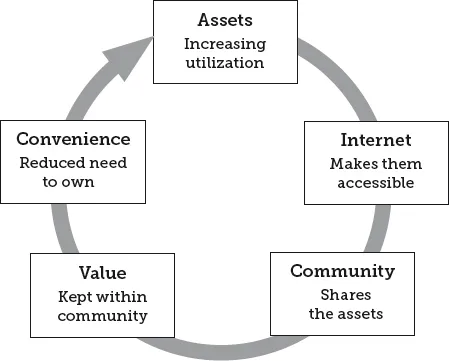

The sharing economy is the value in taking underutilized assets and making them accessible online to a community, leading to a reduced need for ownership of those assets.

(Even more abruptly, I say the sharing economy is the value in redistributing excess to a community, or getting “slack to the pack.”)

My definition has five main limbs.

1 Value

Sharing economy platforms create reciprocal economic value. Usually, they are revenue-generating e-commerce sites, or have the potential to be revenue-generating. Sometimes, the revenue motive appears incidental or exists only to make the service sustainable. For example, it is free to swap books on BookMooch. Users get points by mailing their old books to someone else and redeem points by requesting someone else’s books. This earns the website precisely nothing. However, BookMooch is able to make revenue from its visitors when they click on Amazon affiliate links for second-hand books that are not available on their website.

Sometimes, goods and services in the sharing economy are changing hands through a gift economy. On yerdle, people gift their unwanted objects, but the users will be monetized later on, most likely through the purchase of credits. As the title suggests, my focus in this book is on the business of sharing. While TeamUp! Against Cancer, a marketplace that connects cancer victims with local volunteers, is a great philanthropic initiative, I will be looking in more detail at a business like TaskRabbit, a marketplace where people get paid for doing chores and the platform earns commission.

2 Underutilized assets

In the sharing economy, the assets on platforms can be anything from yachts to baby clothes to dogs. BorrowMyDoggy is a UK startup that matches up dog owners with dog-less dog lovers, with both parties paying an annual subscription. Dog owners get a break from looking after their canine. Non-dog owners get the novelty of having a dog on demand. Alien as it would appear to their doting owners, even dogs can be viewed as assets. Services in the sharing economy, such as mowing someone’s lawn or helping them to set up a blog, are usually the output of intangible assets like time and expertise.

The value in all of these assets is in their so-called “idling capacity”: the periods of time when extra value could be extracted from them. Idling capacity is a notion that was first systematically studied and measured in the context of industrial processes. The sharing economy applies the same ruthless logic of how best to run an aluminum smelter to all of our assets. That means turning an asset’s downtime into revenue, whether that asset is a bicycle or the time of someone who could be riding that bicycle to deliver a package.

3 Online accessibility

For utilization to increase, these assets need to be made accessible. “Sharing” in the context of the sharing economy has become shorthand for “making accessible,” a process that happens once assets are listed online. Making accessible can mean selling, for example through the peer-to-peer (P2P) e-commerce pioneer and granddaddy of the sharing economy, eBay. It can mean renting such as through Airbnb, gifting as we just saw with yerdle, or even swapping. On Swapz, you can find exchanges such as a DJ offering to play for free in return for some maintenance to his van.

4 Community

But making underutilized assets accessible is not enough: the assets need to move within a community. Community means more than just supply and demand. In successful sharing economy businesses, communities of users engage with each other above and beyond their transactional needs. They trust each other. They are values-based and, as we will see, police these values from internal threats and defend them from external ones. Often, these communities are built around interest groups. On SabbaticalHomes.com, the people swapping homes are all university academics. On a website like DogVacay, where dog owners board their dogs with ordinary people rather than at kennels, the community is chatty on social media and united by a love of dogs.

Community is often the decisive difference between a sharing economy business and a traditional rental one like CORT, the world’s largest supplier of rental furniture. Although CORT has the potential to be a sharing economy business, there is no sense of the community behind the business: no reviews, profiles, ability for users to message each other, or customer stories. The people and small businesses who rent the furniture are effectively invisible. CORT’S owners, Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway conglomerate, must view previous renters of their furniture as unfortunate reminders of its unpalatable second-handness rather than a strength to be leveraged.

5 Reduced need for ownership

Once people can access assets within a community, it leads to a reduced need to own those assets. Rise Art is a website that lets people rent fine art. If you move house often or do not want to stare at the same art for years on end, it makes sense to rent paintings. Or consider how each shared Zipcar can take 17 other cars off the road.1 This makes Zipcar fundamentally different from a traditional rental car business like Alamo. While Alamo’s core business is supplying supplementary cars at airports, Zipcar deploys its cars around cities, reducing the need to own them in the first place. One consequence of such business models is that goods become services. As Arun Sundararajan, a professor at New York University and the sharing economy’s leading academic, notes, “Sharing economy businesses are spawning a range of efficient new ‘as-a-service’ business models in industries as diverse as accommodation, transportation, household appliances, and high-end clothing.”

FIGURE 1.1 The sharing economy: increasing asset utilization

The two sharing models

If the end-user merely accesses the inventory, then who owns it? Sharing economy companies come in two flavors. Some are business-to-consumer (B2C). Others are P2P. Consider the differences between Zipcar’s business model and that of another car rental business, RelayRides. Zipcar is a B2C business that buys and maintains a fleet of new vehicles that it rents to drivers. RelayRides, on the other hand, is a P2P marketplace that allows individuals to rent out their own cars to other drivers. Although their ends may be similar—providing convenient access to a car—their means differ in two ways. On a P2P marketplace, the inventory is already out there, making RelayRides a leaner business model. Furthermore, the provider of the service is not a company but a person. If there is an issue with my Zipcar booking, I contact their customer service team. If there is a problem with my RelayRides car, my first port of call is the individual owner.

This is not to say there is anything unprofessional about having to deal with an individual rather than a company. Sellers on P2P platforms are not incorporated businesses as we know them but micro-entrepreneurs, often running highly slick operations. Instead of a corporate brand, they leverage their personal brand through a profile page. Instead of a Yellow Cab taking me downtown, it is Eddie. Instead of a Hilton hotel checking me in, it is Cara. The buyers too are often more than passive consumers, as I felt by getting to know Eddie and Cara. As we will see, in this new economy “consumers” can also be lenders or investors. Thus, I avoid the term “consumer-to-consumer” or “C2C” when talking about P2P marketplaces. Sharing economy ventures that are B2C can create astonishing efficiencies. But P2P ones are blurring the once-neat divide between business and consumer, in the process transforming society itself.

Drawing a line

It is a mystery as to who first used the term “sharing economy.” Perhaps it is appropriate that its ownership is shared. But it has left the term without a guardian and vulnerable to loose definitions. The term’s definition has also been stretched by countless startups trying to jump on the sharing economy bandwagon. Why would a startup want to do that? Firstly, sharing economy companies carry extraordinary moral clout. They are coolly collaborative and linked to the local and sustainable. That can make the first major challenge many startups face—attracting talent and potentially co-founders to work for little or nothing—a lot easier. Secondly, sharing economy businesses benefit from disproportionate amounts of positive PR that can reel in a startup’s first customers. Thirdly, the hype around the sharing economy helps stoke racy company valuations that let startups raise finance with less dilution of the founders’ shareholdings. Little wonder that many entrepreneurs try to pin a sharing economy ribbon to their startup’s scruffy lapel.

One consequence of the loose definition of the sharing economy has been the impossibility of accurately market-sizing it. Some companies have only one foot in the sharing economy, adding further layers of complexity.

People auctioning unwanted second-hand goods on eBay are certainly getting “slack to the pack.” However, 75% of eBay’s marketplace revenue comes from merchants selling new, fixed-price goods.2 Attempts have indeed been made to market-size the sharing economy, with estimates ranging from $3.5 billion to the low tens of billions,3 a large range that reflects the porous boundaries of the term. Nonetheless, while there will always be gray areas and not every sharing economy company will meet each of my five criteria, it is time to rein in the definition of the sharing economy. If the sharing economy is to know what it is, it must be ready to say what it is not. Entrepreneurs and journalists should be unafraid to draw a line. So that is my definition, at least for now. Please disagree with me by tweeting@alexmstephany. Words are worth wrestling over.

When sharing is not sharing

You would be forgiven for reading my definition of the sharing economy and thinking, this has nothing do with sharing: this is about renting and selling! If so, you would not be the first person to find the term confusing if not downright misleading. Martin Varsavsky, the founder of Fon, stressed to me, “Renting is not always sharing. Renting is renting.” In a thinly veiled dig at Airbnb, Ed Kushins, the founder of home-swapping platform HomeExchange has said, “Sharing is sharing and not paying.”4 At least the rental of assets involves them being used by multiple parties but, as we noted, “sharing” can also apply to the sale of goods. Either way, “sharing” carries none...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- The Billion Dollar Moustache

- Chapter 1: Architects: Building on New Ground

- Chapter 2: We the People: Selfish Sharers

- Chapter 3: Founders: Visionaries and Doers

- Chapter 4: Investors: All Bets Are On (All $4 Billion of Them)

- Chapter 5: Corporates: Angry, Afraid—and In

- Chapter 6: Governments: Fits and Starts

- A Shared Future?

- Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms

- Appendix

- Index