![]()

1

CHAPTER ONE

THE BASICS

In this chapter, you will learn about the bouncing ball, the pendulum, and the arc, which are the basis for all animated movement. You will also experiment with timing and spacing of images and create your first acting scenes.

Animation begins where live action gives up.

—Kaj Pindal, award-winning animator, director, and writer

OUTER SPACE: DEFINING AND DISTORTING VOLUMES

There is no “one way” to animate anything. That’s the beauty of the medium. Animated performance is as varied as you are: How a character moves, talks, and interacts with others will depend on the story context, the character’s mood, and whether it is human, animal, or neither. Most important, every artist has a different life experience that can add depth and variety to animated acting and bring even the most basic assignments to life.

Animated characters can defy gravity, but they are still affected by it. We have to learn the rules before breaking them. We start with some simple exercises that analyze the effects of gravity and timing on animation.

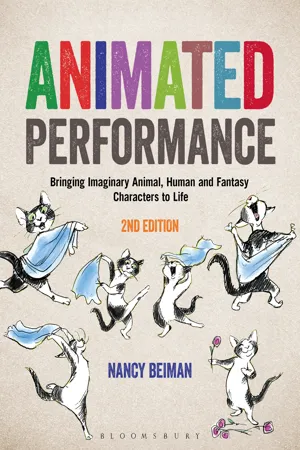

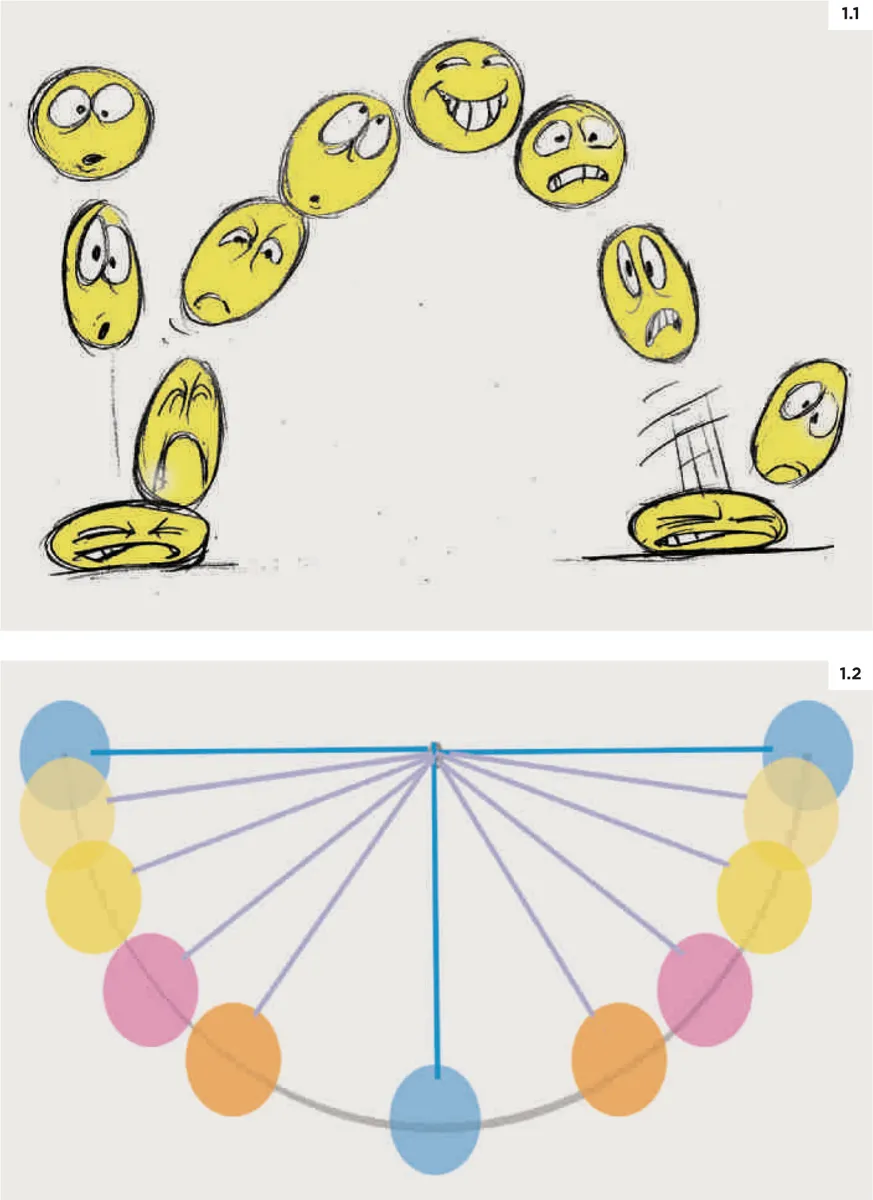

The bouncing ball and the pendulum actions, as shown in Figs. 1.1 and 1.2, determine the weight of a character and the timing of its movement.

1.1 and 1.2 Two movements are the basis of all animated action: the bouncing ball and the pendulum.

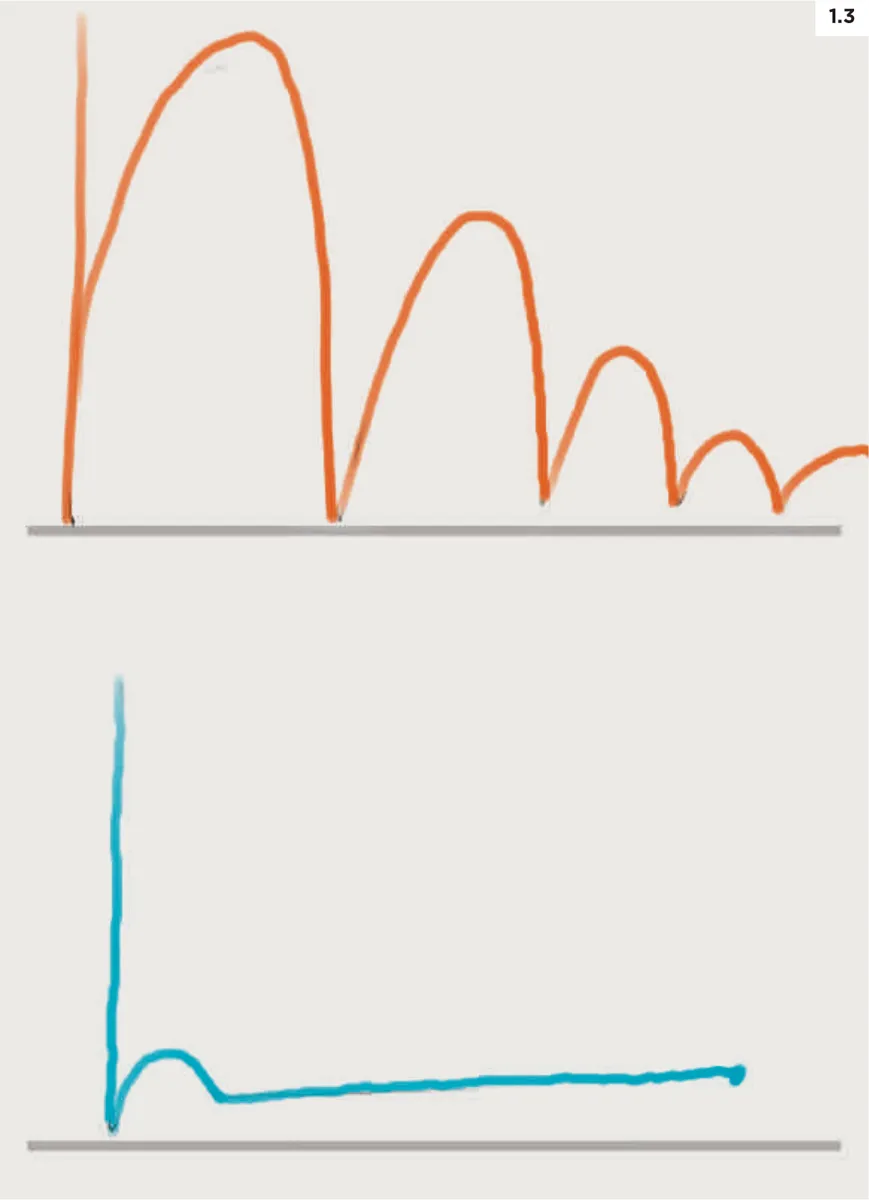

An additional principle—the arc—determines the intensity and direction of the movement. Pendulums and bouncing balls naturally move along an arc-shaped path, with one major difference: The pendulum’s arc will remain constant, while the bouncing ball’s arc will vary depending on the force of the first impact and the ball’s weight and composition. Think of an arc as a motion guide, for that is exactly what it is. By varying the height of the bouncing ball’s arcs in descending order, as shown in Fig. 1.3, you create variations in its movement that indicate its composition and the effect of inertia, which eventually brings it to a stop. Bouncing balls are entirely affected by outside forces; they do not willfully direct their movements.

1.3 The arcs in these two examples suggest how different materials might bounce before we even place the ball along the motion guide.

Exercise #1: Bouncing ball (Part 1)

1. Draw a horizontal line along the bottom of the picture plane (screen or paper). This will be your floor plane for a bouncing ball. The entire exercise will appear on one image or page.

2. Draw a straight line entering from the top left-hand side of the screen and intersecting the floor plane; then draw a series of arcs, gradually decreasing in size, from left to right, as seen in Fig. 1.3. The more arcs you draw, the faster the bounce will be.

3. Be sure to have the bottom of each arc make contact with the floor plane. The arcs should also decrease in size as you move to the right-hand side of the frame. Remember, this “ball” is not a living character that controls its own movement but is only reacting to simple physics.

Adjusting the volume

After the arcs set the height of each bounce, we can suggest the ball’s composition and weight by varying its flexibility, or deformation of its volume. Volume is best defined as the normal size of the ball or character, in three dimensions. Volumes will distort in the animation of this bounce, but within limits (think of a rubber ball, not chewing gum), and the ball will return to its normal size after the action is completed. The more extreme the stretch and squash, the more flexible the material. For example, a soft rubber ball moving at a high speed will squash quickly as it hits, stretch as it moves out of the squash, and maintain high arcs on the second or third bounce before slowing down as a reaction to gravity and inertia, possibly ending with a few quick little bounces. A very heavy ball will deform very slightly as it hits, and possibly only “bounce” once along a very limited arc before rolling to a stop.

It’s relatively easy to maintain the volume on all of the images when your character is a ball. It becomes more difficult to do this with complex characters, especially in hand-drawn animation. Sometimes, a hand-drawn character might lose volume on all or part of its body if care is not taken to keep the distortions believable. Digitally animated characters, on the other hand, must be rigged so as to believably deform the “perfect” volumes of their characters. It is this deformation that gives your characters a feeling of weight and solidity in action, even when it is only a bouncing ball.

1.4 The amount of distortion on the ball’s volume and the height of the arcs indicate whether it is made of soft or hard material, as shown in Fig. 1.4. The first ball is flexible, while the second one is heavy and solid.

Bouncing ball (Part 2)

4. Draw a starting point for the ball just inside the picture plane along the straight line. After you have decided what material the ball is made of, indicate the high point of your ball’s movement along each of the arcs. These are known as key poses, or extremes. They should, for this exercise, retain the normal volume of the ball—no distortion or stretch should be present.

5. Next, draw additional key poses for the squash of the ball where each arc intersects the floor plane. Here, knowledge of your material becomes important. The severity of the squash will indicate the composition or softness of the ball. Even a bowling ball will deform slightly when it hits the ground and slow down a bit at the top of its very limited arc. The squashes also may not be identical; they will deform less as the ball loses momentum. Be sure to maintain the ball’s volume even in a strong squash—it should be a believable distortion.

6. After you have added your key poses or extremes to the low and high points of the arcs, add “in-between” poses in a different color. Indicate the spacing of the inbetween poses by first drawing charts indicating their placement along the arcs with little marks, as shown in Fig. 1.5. These marks roughly indicate the center of each of the balls on the inbetweens. Charting will become more important when we work with more complex characters; a character’s arms, legs, and body may move at different rates, resulting in time variations on a single image. But for now, let’s stick to the bouncing ball.

The high point of ...