![]()

1

Design Ability

Our job is to give the client, on time and on cost, not what he wants, but what he never dreamed he wanted; and when he gets it, he recognises it as something he wanted all the time.

Denys Lasdun, architect.

Everyone can – and does – design. We all design when we plan for something new to happen, whether that might be a new version of a recipe, a new arrangement of the living room furniture, or a new layout of a personal web page. The evidence from different cultures around the world, and from designs created by children as well as by adults, suggests that everyone is capable of designing. So design thinking is something inherent within human cognition; it is a key part of what makes us human.

We human beings have a long history of design thinking, as evidenced in the artefacts of previous civilisations and in the continuing traditions of vernacular design and traditional craftwork. Everything that we have around us has been designed. Anything that isn’t a simple, untouched piece of nature has been designed by someone. The quality of that design effort therefore profoundly affects our quality of life. The ability of designers to produce effective, efficient, imaginative and stimulating designs is therefore important to all of us.

To design things is normal for human beings, and ‘design’ has not always been regarded as something needing special abilities. Design ability used to be somehow a collective or shared ability, and it is only in fairly recent times that the ability to design has become regarded as a kind of exceptional talent. In traditional, craft-based societies the conception, or ‘designing’, of artefacts is not really separate from making them; that is to say, there is usually no prior activity of drawing or modelling before the activity of making the artefact. For example, a potter will make a pot by working directly with the clay, and without first making any sketches or drawings of the pot. In modern, industrial societies, however, the activities of designing and of making artefacts are usually quite separate. The process of making something does not normally start before the process of designing it is complete.

Although there is so much design activity going on in the world, the ways in which people design were rather poorly understood for rather a long time. Design ability has been regarded as something that perhaps many people possess to some degree, but only a few people have a particularly strong design ‘gift’. Of course, we know that some people are better designers than others. Ever since the emergence of designers as professionals, it has appeared that some people have a design ability that is more highly developed than other people – either through some genetic endowment or through social and educational development. In fact, some people are very good at designing. However, there are now growing bodies of knowledge about the nature of designing, and about the core features or aspects of design ability.

Through research and study there has been a slow but nonetheless steady growth in our understanding of design ability. The kinds of methods for researching the nature of design ability that have been used have included:

Interviews with designersThese have usually been with designers who are acknowledged as having well-developed design ability, and the methods have usually been conversations or interviews that sought to obtain these designers’ reflections on the processes and procedures they use – either in general, or with reference to particular works of design.

Observations and case studiesThese have usually been focused on one particular design project at a time, with observers recording the progress and development of the project either contemporaneously or post hoc. Both participant and non-participant observation methods have been included, and varieties of real, artificially constructed and even re-constructed design projects have been studied.

Experimental studiesMore formal experimental methods have usually been applied to artificial projects, because of the stringent requirements of recording the data. They include asking the experiment participants to ‘think aloud’ as they respond to a given design task. These statements and the associated actions of the participants are sub-divided into short ‘protocols’ for analysis. Both experienced designers and inexperienced (often student) designers have been studied in this way.

SimulationA relatively new development in research methodology has been the attempt of artificial intelligence (AI) researchers to simulate human thinking through artificial intelligence techniques. Although AI techniques may be meant to supplant human thinking, research in AI can also be a means of trying to understand human thinking.

Reflection and theorisingAs well as the empirical research methods listed above, there has been a significant history in design research of theoretical analysis and reflection upon the nature of design ability.

We therefore have a varied set of methods that have been used for research into design ability. The set ranges from the more concrete to the more abstract types of investigation, and from the more close to the more distant study of actual design practice. The studies have ranged through inexperienced or student designers, to experienced and expert designers, and even to forms of non-human, artificial intelligence. All of these methods have helped researchers to develop insights into what has been referred to as ‘designerly’ ways of thinking.

The use of a variety of research methods has been required because to understand design ability it is necessary to approach it slightly obliquely. Like all kinds of sophisticated cognitive abilities, it is impossible to approach it directly, or bluntly. For example, designers themselves are often not very good at explaining how they design. When designers – especially skilled, successful designers – talk spontaneously about what they do, they talk almost exclusively about the outcomes, not the activities. They talk about the products of their designing, rather than the process. This is a common feature of experts in any field. Their enthusiasm lies in evaluating what they produce, and not in analysing how they produce it.

Sometimes, some designers can even seem to be wilfully obscure about how they work, and where their ideas come from. The renowned (perhaps even notorious) French designer Philippe Starck is known to suggest that design ideas seem to come to him quite magically, as if from nowhere. He has said that he has designed a chair while sitting in an aircraft during take-off, in the few minutes while the ‘fasten seat belts’ sign was still on. Perhaps the instruction to ‘fasten seat belts’ was an inspirational challenge to his designing. Of the design process of his iconic lemon squeezer for the Italian kitchenware manufacturer Alessi, he has said that, in a restaurant, ‘this vision of a squid-like lemon squeezer came upon me …’ And so, Juicy Salif, the lemon squeezer (Figure 1.1), was conceived, went into production and on to become a phenomenally successful product in terms of sales (if not necessarily in terms of its apparent function).

Designers can also seem to be quite arrogant in the claims that they make. Perhaps it seems arrogant for the architect Denys Lasdun to have claimed that ‘Our job is to give the client … not what he wants, but what he never dreamed he wanted …’ But I think that we should try to see through the apparent arrogance in this statement, to the underlying truth that clients do want designers to transcend the obvious and the mundane, and to produce proposals which are exciting and stimulating as well as merely practical. What this means is that designing is not a search for the optimum solution to the given problem, but that it is an exploratory process. The creative designer interprets the design brief not as a specification for a solution, but as a starting point for a journey of exploration; the designer sets off to explore, to discover something new, rather than to reach somewhere already known, or to return with yet another example of the already familiar.

1.1 Philippe Starck’s ‘Juicy salif’ lemon squeezer for alessi.

I do not want to imply here that designing is indeed a mysterious process, but I do want to suggest that it is complex. Although everyone can design, designing is one of the highest forms of human intelligence. Expert designers exercise very developed forms of certain tacit, deep-seated cognitive skills. But, as we shall see later, it is possible to unravel even Philippe Starck’s visionary Juicy Salif moment into a much less mysterious explanation in terms of the context of the task he was undertaking, and of the iconography upon which Starck drew for inspiration.

Asking Designers about what they Do

The spontaneous comments of designers themselves about designing can seem obscure, but it is possible to gain some insights by interviewing them more carefully, and interpreting the implications of their responses. Asking designers about what they do is perhaps the simplest and most direct form of inquiry into design ability, although this technique has not in fact been practised extensively.

Robert Davies interviewed members of the UK-based ‘Faculty of Royal Designers for Industry’. This is an élite body of designers, affiliated to The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, or the Royal Society of Arts (RSA) as it is more conveniently known. The number of Royal Designers for Industry (RDIs) is limited to a maximum of 100 at any given time, and they are selected for the honour of appointment to the Faculty on the basis of their outstanding achievements in design. So choosing RDIs for interview is one way of ensuring that you are interviewing eminent designers with a record of achievement and accomplishment; that they do indeed possess and use a high level of design ability. At the time Davies conducted his interviews there were sixty-eight RDIs, ranging over professions such as graphic design, product design, furniture design, textile design, fashion design, engineering design, automotive design and interior design. He interviewed thirty-five of these, conducting the interviews informally at their own homes or places of work, but video-recording the discussions.

Davies was especially interested in the creative aspects of design ability, focusing on asking the designers how they thought that they came up with creative insights or concepts. But his informal interviews tended to range widely over many aspects of the design process, and on what seems to make some people ‘creative’. One theme that recurred in their responses was the designers’ reliance on what they regarded as ‘intuition’, and on the importance of an ‘intuitive’ approach. For example, the architect and industrial designer Jack Howe said, ‘I believe in intuition. I think that’s the difference between a designer and an engineer … I make a distinction between engineers and engineering designers … An engineering designer is just as creative as any other sort of designer.’ This belief in ‘intuition’ seems surprising in someone like Jack Howe, whose design work consistently looked rather austere and apparently very rational. The product designer Richard Stevens made a rather similar comment about the difference between engineering and designing: ‘A lot of engineering design is intuitive, based on subjective thinking. But an engineer is unhappy doing this. An engineer wants to test; test and measure. He’s been brought up this way and he’s unhappy if he can’t prove something. Whereas an industrial designer, with an Art School training, is entirely happy making judgements which are intuitive.’

What these designers are saying is that they find some aspects of their work appear to them to be natural, perhaps almost unconscious, ways of thinking, and they find that some other types of people (notably, the engineers with whom they come into contact in the course of their work) are uncomfortable with this way of thinking. They believe that this ‘intuitive’ way of thinking may be something that they inherently possess, or it may be something that they developed through their education. Making decisions, or generating proposals, in the design process is something that they feel relaxed about, and for which they feel no need to seek rational explanations or justifications. But it may be that they are overlooking the experience that they have gathered, and in fact their ‘intuitive’ responses may be derived from these large pools of experience, and from prior learning gained from making appropriate, and inappropriate, responses in certain situations. We all behave intuitively at times, when we respond in situations that are familiar.

However, designers are perhaps right to call their thinking ‘intuitive’ in a more profound sense, meaning that it is not based upon conventional forms of logical inferences. The concept of ‘intuition’ is a convenient, shorthand word for what really happens in design thinking. The more useful concept that has been used by design researchers in explaining the reasoning processes of designers is that design thinking is abductive: a type of reasoning different from the more familiar concepts of inductive and deductive reasoning, but which is the necessary logic of design. It is this particular logic of design that provides the means to shift and transfer thought between the required purpose or function of some activity and appropriate forms for an object to satisfy that purpose. We will explore this logic of design later.

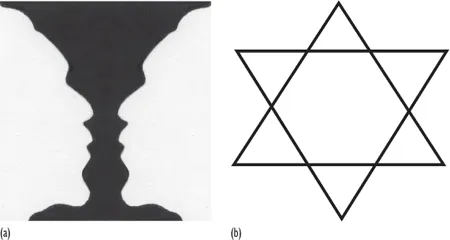

Another theme that emerged from Davies’s interviews with these leading designers is related to this tricky relationship between the ‘problem’ (what is required) and its ‘solution’ (how to satisfy that). Designers recognise that problems and solutions in design are closely interwoven, that ‘the solution’ is not always a straightforward answer to ‘the problem’. A solution may be something that not only the client, but also the designer ‘never dreamed he wanted’. For example, commenting on one of his more creative designs, the furniture designer Geoffrey Harcourt said, ‘As a matter of fact, the solution that I came up with wasn’t a solution to the problem at all. I never saw it as that … But when the chair was actually put together, in a way it quite well solved the problem, but from a completely different angle, a completely different point of view.’ This comment suggests something of the perceptual aspect of design thinking – like seeing the vase rather than the faces, in the well-known ambiguous figure (Figure 1.2a). It implies that designing utilises aspects of emergence; relevant features emerge in tentative solution concepts, and can be recognised as having properties that suggest how the developing solution-concept might be matched to the also developing problem-concept. Emergent properties are those that are perceived, or recognised, in a partial solution, or a prior solution, that were not consciously included or intended. In a sketch, for example, an emergent aspect is something that was not drawn as itself, but which can be seen in the overlaps or relationships between the drawn components (Figure 1.2b). In the process of designing, the problem and the solution develop together.

Given the complex nature of design activity, therefore, it hardly seems surprising that the structural engineering designer Ted Happold suggested to Davies that, ‘I really have, perhaps, one real talent, which is that I don’t mind at all living in the area of total uncertainty.’ Happold certainly needed this talent, as a leading member of the structural design team for some of the most challenging buildings in the world, such as the Sydney Opera House and the Pompidou Centre in Paris, and in his own engineering design work in lightweight structures. The uncertainty of design is both the frustration and the joy that designers get from their activity; they have learned to live with the fact that design proposals may remain ambiguous and uncertain until quite late in the process. Designers will generate early tentative solutions, but also leave many options open for as long as possible; they are prepared to regard solution concepts as temporarily imprecise and often inconclusive.

1.2 (a) Ambiguity: vase or faces? (b) Emergence: two overlapping triangles also contain emergent features such as a hexagon and a six-pointed star.

Another common theme from Davies’s interviews is that designers need to use sketches, drawings and models of all kinds as a way of exploring problem and solution together, and of making some progress when faced with the complexity of design. For example, Jack Howe said that, when uncertain how to proceed, ‘I draw something. Even if it’s “potty” I draw it. The act of drawing seems to clarify my thoughts.’ He means that, when faced with a blank sheet of paper, he can at least draw something that may at first seem silly or inappropriate, but which provides a starting point to which he can respond; if it doesn’t seem right, why doesn’t it? Designing, it seems, is difficult to conduct by purely internal mental processes; the designer needs to interact with an external representation. The activity of sketching, drawing or modelling provides some of the circumstances by which a designer puts him- or herself into the design situation and engages with the exploration of both the problem and its solution. There is a cognitive limit to the amount of complexity that can be handled internally; sketching provides a temporary, external store for tentative ideas, and supports the ‘dialogue’ that the designer has between problem and solution.

Summarising from the interviews with RDIs, Robert Davies and Reg Talbot also identified some personality characteristics which seem key to making these people successful in dealing constructively with uncertainty, and the risks and opportunities that present themselves in the process of designing. ‘One of the characteristics of these people,’ they suggested, ‘is that they are very open to all kinds of experience, particularly influences relevant to their design problem. Their awareness is high. They are sensitive to nuances in their internal and external environments. They are ready, in many ways, to notice particular coincidences in the rhythm of events which other people, because they are less aware and less open to their experience, fail to notice. These designers are able to recognise opportunities in the way coincidences offer prospects and risks for attaining some desirable goal or grand scheme of things. They identify favourable conjectures and become deeply involved,...