![]()

1

Introduction – The Importance of Epistemology in Management Research

Organizational scholars can resist philosophy as long as they assume the ends of institutions and the current definitions of those ends by participants or scholars.

(Zald, 1996: 257)

The main objective of this book is to provoke debate and reflection upon the different ways in which we engage with management and organization when undertaking research. Our argument is that how we come to ask particular questions, how we assess the relevance and value of different research methodologies so that we can investigate those questions, how we evaluate the outputs of research, all express and vary according to our underlying epistemological commitments. Even though they often remain unrecognized by the individual, such epistemological commitments are a key feature of our pre-understandings which influence how we make things intelligible. Therefore this book tries to offer the reader an overview of the principal epistemological debates in social science and how these lead to, and are expressed in, different ways of conceiving and undertaking management and organizational research. Obviously, in a book of this size it is impossible to do justice to the full range of issues raised by this objective. Instead we hope that it will provide a concise and accessible introduction which will stimulate the reader’s interest in epistemological issues and their implications for thinking about management and organization.

One reason why we feel that these objectives are important derives from our experience that students in the UK are increasingly expected to demonstrate a reflexive understanding of their own epistemological commitments as they engage with management and organizations in undertaking empirical research for theses and dissertations. Previously, researchers in management studies have been criticised for being uncritical and ill informed in their adoption of particular positions with regard to research (see, for example, Whitley, 1984a). This is beginning to change and some of these issues are covered in a disparate set of journals (e.g. Organization Studies; Academy of Management Review; Organization; Accounting, Organizations and Society; and Human Relations, to name only a few). Their style and language-in-use, however, are often daunting and inaccessible to those yet to be admitted into the conventions of philosophical discourse.

Nevertheless many students and researchers are still expected to read and comprehend a burgeoning literature which increasingly deploys epistemological concepts and language. For instance, in order to understand the current debate in the literature between modernists, critical modernists and postmodernists (whether this is about corporate strategy, human resources management or accountancy etc.) a high level of prior epistemological understanding is essential. Hence a key rationale for this book is to give readers an accessible grounding in epistemology that helps them to comprehend these ongoing debates and to engage with their own pre-understandings when trying to make sense of management and organization.

An underlying assumption of the book is that both within and outside our work organizations our behaviour is internally motivated, and internally justified, by what we believe about ‘the world’. At the same time, even though we might not be immediately conscious of it, everyone has a view about what demarcates justified from unjustified belief. Indeed our claims about being rational or irrational or about what is true as opposed to what is false are tacitly grounded in such implicit differentiations. Perhaps these ways of thinking are so embedded in our language and culture that if we were to reflect upon them they would appear to be a matter of common sense and therefore natural and irresistible. Nevertheless our debates and conjectures about what is true presuppose prior agreement (a pre-understanding that is shared) about how we determine whether or not something is true. Similarly, any epistemological analysis of the grounds of certain knowledge or the scientificity of truth claims involves ontological assumptions about the nature of the world (Bhaskar, 1975). This signifies that in our everyday lives we are all epistemologists – or at least we routinely take certain epistemological conventions to be so self-evident we rarely feel the need consciously to express, discuss or question them. Indeed it may be the case that to notice and then consciously to reflect upon such conventions are the first steps in making the commonsensical and self-evident, precarious and problematic.

Although scientists and philosophers have debated epistemological questions since the time of Plato and Aristotle, the term ‘epistemology’ remains somewhat esoteric for most people and usually it obfuscates more than it reveals. However once we break down the word into its constituent parts it seems much less daunting. The word derives from two Greek words: ‘episteme’ which means ‘knowledge’ or ‘science’; and ‘logos’ which means ‘knowledge’, ‘information’, ‘theory’ or ‘account’. This aetiology demonstrates how epistemology is usually understood as being concerned with knowledge about knowledge. In other words, epistemology is the study of the criteria by which we can know what does and does not constitute warranted, or scientific, knowledge. Therefore it would seem that epistemology assumes some vantage point, one step removed from the actual practice of science itself. At first sight this promises to provide some foundation for scientific knowledge: a methodological and theoretical beginning located in normative standards that enable the evaluation of knowledge by specifying what is permissible and hence the discrimination of warranted belief from the unwarranted, the rational from the irrational, the scientific from pseudoscience.

According to Richard Rorty, a North American philosopher, this notion that epistemology is the discipline that enables the judgement of all other disciplines arose in seventeenth-century Europe. It expresses the desire ‘to find “foundations” to which one might cling, frameworks beyond which one must not stray, objects which impose themselves, representations which cannot be gainsaid’ (1979: 315). Accordingly, by seeking to explain ourselves as knowers, by telling us how we ought to arrive at our beliefs, epistemology is pivotal to science since ‘proper’ scientific theorizing can only occur after the development of epistemological theory. It follows that a key question must be: how can we develop an epistemological theory – a science of science?

One answer to the above question is suggested by Quine (1969) where he argues that epistemology should abandon any philosophical questions and become a branch of experimental psychology which analyses human cognitive processes through empirical research. The aim would be to produce a science of science where the laws of cognition tell us why and how we hold the theories that we do. At first sight this programme seems an eminently sensible solution – to paraphrase Quine, a science of science which is science – but one which, incidentally, may make this book rather pointless. However two interrelated problems arise here.

First, since epistemology determines the criteria by which justified knowledge is possible, it must not itself take for granted the results of particular forms of empirical inquiry such as experimental psychology. Secondly, we cannot presuppose that there exists some analytical space that may be occupied by experimental psychologists that is somehow free from the very philosophical assumptions that influence how we engage in justifiable ‘knowing’. Experimental psychology is itself based upon a plethora of philosophical assumptions regarding the possibility of knowledge in experimental psychology which are themselves contestable. So it would appear that Quine’s rejection of philosophical questions merely creates an unsustainable philosophical vacuum that is promptly filled by default by some new, but unrecognized, set of philosophical commitments.

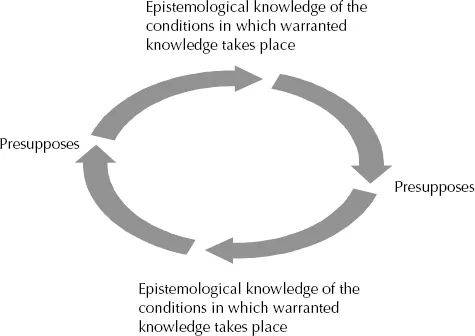

Here the paradox, as shown in Figure 1.1 below, is that epistemology confronts a fundamental problem of circularity, from which it cannot escape, in that any theory of knowledge (i.e. any epistemology) presupposes knowledge of the conditions in which knowledge takes place. In effect, this prevents any grounding of epistemology in what purports to be scientific knowledge – psychological or otherwise – because one cannot use science in order to ground the legitimacy of science.

Figure 1.1 The circularity of epistemology

Hence the seventeenth-century promise of epistemology to provide secure foundations for scientific knowledge seems a forlorn hope precisely because of circularity. For instance Otto Neurath has described this problem of circularity in terms of a nautical metaphor:

we are like sailors who on the open sea must reconstruct their ship but are never able to start afresh from the bottom … They make use of some drifting timber of the old structure, to modify the skeleton and the hull of their vessel. But they cannot put into dock in order to start from scratch. During their work they stay on the old structure and deal with heavy gales and thundering waves. (1944: 47)

For Neurath the problem of circularity means that we cannot dump philosophy by detaching ourselves from our epistemological commitments so as to assess those commitments objectively – indeed we would depend upon them in order to undertake that task. It follows that there are no secure or incontestable foundations from which we can begin any consideration of our knowledge of knowledge – rather what we have are competing philosophical assumptions about knowledge that lead us to engage with management and organizations in particular ways. Therefore the reader who hopes that this book will provide them with irreducible epistemic standards to guide and improve their research will be disappointed. Perhaps the most we can hope for in considering epistemology is to become more consciously reflexive. This involves an attempt at self-comprehension through beginning to notice and then criticize our own pre-understandings in a more systematic fashion while trying to assess their impact upon how we engage with the social and natural worlds. Such self-comprehension not only entails identifying our epistemological pre-understandings and their philosophical derivation, it also requires us to challenge them by noticing and exploring alternative possible commitments.

The point is that everyone adheres to some theory about what constitutes warranted knowledge – a set of epistemological commitments which provide us with criteria for distinguishing between reliable and unreliable knowledge. If we didn’t have such theories, no matter how tacit, we would never be able to make what we construe as legitimate claims about what we think we know or think we have experienced. Mundane claims such as ‘I saw it with my own eyes’ or ‘The facts speak for themselves’ presuppose that such appeals refer to evidence which is epistemologically legitimate. Such commitments provide us with criteria which we use to assess which kinds of description and explanation of our social or natural worlds are appropriate. Moreover, as we have just shown, closely allied to those commitments are also notions about what might warrant the status of being ‘scientific’. Indeed epistemological commitments also provide tacit answers to questions about:

- What are the origins, nature and limits of scientific knowledge?

- What constitutes scientific practice?

- What are the processes through which scientific knowledge advances or is such progress a forlorn hope?

So, for instance, because of their education and training scientists are commonly thought to be, in principle, objective observers of the world. Their expertise and rigorous deployment of accepted procedures and protocols allow scientists to collect empirical evidence about the social and natural worlds. The apprehended form and content of either world is usually understood to be separate from, or independent of, the methodological means by which scientists engage with it. In other words the data collected, rather than the processes of observation, dictate the findings and theories of science. Mistakes can and do happen: individual scientists may misunderstand the significance of their data, they may make methodological errors and indeed they might be wilfully biased or even corrupt. Nevertheless it is commonly assumed that errors and biases can be corrected through improvements in the training, recruitment and selection of scientists as well as by the surveillance of scientific findings by a wider community of scientists. The key epistemological assumption is that the stock of knowledge advances as scientists actually learn more about the world as well as through the exposure of the fraudulent and the eradication of mistakes through critical processes akin to quality control undertaken by peers. Hence science is progressive; moreover its outputs can be trusted because its ultimate arbiter is to be found in the objective observational processes encoded into its methodology and self-regulation which make it a superior means of knowledge acquisition.

The above account of science expresses what Robert K. Merton (1938–70) called the ‘ethos of science’. In his analysis of seventeenth-century England Merton argues (ibid.: 136–8) that Puritan values that emphasized utility, rationality, empiricism and worldly asceticism contributed significantly to the rise of modern science in England and its subsequent diaspora. In support of this notion he considered that the over-representation of Puritans amongst the founding membership of the Royal Society proffers evidence of the link between Puritanism and the modern scientific community. For Merton these values became embedded in the ethos of science which, now severed from the religious commitments of its founders, enables the production and arbitration of knowledge claims with an objectivity that ‘precludes particularism’.

In 1938 Merton’s account of what he had observed as the scientific ethos was to a degree aimed at defending science from what he saw as Nazism’s anti-intellectual contempt for science which at the time had tied some of the German sciences to an ideology steeped in racism and the occult. Merton summarized this scientific ethos (ibid.: 259) as being composed of four sets of ‘institutional imperatives’: ‘universalism’, the principle that scientific truth is dependent upon pre-established impersonal criteria which ensure intellectual honesty; ‘communism’, the principle that scientific truth is the product of social collaboration; ‘organized scepticism’; and ‘disinterestedness’ where the activities of scientists are subject to rigorous impersonal policing against fraudulent contributions. Thus Merton seems to argue that while modern scientific methodology and epistemology are in many respects an historical evolution of particular religious values, these values are functional to the advancement of science – they aid the search for objectivity and truth. So just as Merton accords science some socio-cultural status by giving credence to the view that the religious values propagated by the reformation ushered in a new science, he also proceeds to accord science an extra-socio-cultural status by in effect arguing that those values enabled science to develop to a level that transcended social influences because of the epistemological protection they afford.

The notion that science is a mode of inquiry that transcends social influences so that it can be free from ideological contamination accords with Weber’s demand for a value-free social science (1949). Here Weber made a categorical distinction between empirical facts and value dispositions: the former derive from a cognitively accessible reality, whereas the latter derive from cultural dispositions. For Weber science dealt with facts; it does not and cannot resolve matters of value – a commitment that is adhered to by many contemporary scholars of management and organization. An effect of this stance is to render scientific activities as sociologically unproblematic and functional to the advancement of warranted knowledge.

Of course, as we shall show in this book, such a view of science as value-free is itself grounded in a particular epistemological tradition which when subject to critical examination becomes highly contentious. Moreover that it is only a particular tradition implies the existence of heterodox alternatives which may be just as significant if less familiar and commonsensical. Indeed criticizing the expression of Merton’s and Weber’s views in management and organization as an establishment myth is an increasingly popular pastime, albeit now more commonly associated with the political Left rather than the Right. Often, but by no means exclusively, such attacks will tacitly accord with Bloor’s view that knowledge

is whatever men take to be knowledge. It consists of those beliefs which men (sic) confidently hold to and live by … what is collectively endorsed, leaving the individual and idiosyncratic to count as mere belief. (1976: 2–3)

Here Bloor is taking the position that knowledge and science are the arbitrary outputs of social processes from which no one is exempted – there are no objective ways of discriminating the warranted from the unwarranted – all we have are just different culturally derived ways of knowing the world which vary in their substance and to the extent that they have been accorded social legitimation. From this perspective Merton’s ethos of science should not be seen as defining clear social obligations to which scientists conform. Rather they may be understood as ‘flexible vocabularies employed by participants in their attempts to negotiate suitable meanings for their own and others’ acts in various social contexts’ (Mulkay, 1979: 72) – vocabularies which are bounded by the social and technical cultures shared by the scientists’ particular problem-centred community. While the unorthodox might not be allowed a public forum since their assertions are outside the accepted repertoire, the precise meaning of the orthodoxy has to be re-established through symbolic negotiation, particularly when new domains or problems emerge (ibid.: 78–95).

Of course it would be interesting, if also rather mischievous, to speculate upon what Bloor or Mulkay would make of Merton’s target, Nazi science and its repercussions, since it would seem that its epistemic status would be equivalent to any other body of knowledge which had been collectively endorsed: just another culturally derived process which presumably cannot therefore be criticized because all the critic would be doing is imposing their own culturally embedded beliefs?

However the point to which we wish to limit ourselves here is merely that our epistemological commitments influence the processes through which we develop what we take to be warranted knowledge of the world. Such deeply held taken-for-granted assumptions about how we come ‘to know’ influence what we experience as being true or false, what we mean by true or false, and indeed whether we think that true and false are viable constructs. As we shall show, this is even the case where, as is increasingly popular in management and organizational research, Merton’s ethos is rejected in favour of a view of science as a relative outcome of intuition, paradigm, metaphor, discourse, social convention or fashion. Even to say that there can be no reliable knowledge (in Merton’s sense) beyond some ethnocentric collective endorsement, and hence cast doubt upon the relevance of ...