![]() Part 1

Part 1

Customers and Markets ![]()

Customer Centrality

Customer centrality is the view that the customer’s needs, wants and predispositions must be the starting-point for all decision-making within the organisation.

The idea that the customer should be at the centre of everything we do as marketers is the driving force behind all marketing planning. In any question of marketing, one should always begin with the customer or consumer: in many cases, the customer and the consumer are the same person, but not always. True customer centrality means that the firm should be seeking to create value for customers: this is not done from a sense of altruism, but rather from the viewpoint that, unless we create value for customers, they will not offer value (i.e. money) in return. The concept has been credited to Peter Drucker, who is quoted as saying ‘We are all marketers now’, and for stating that the sole function of any business is to create a customer. He also said,

Customer centrality is a matter of finding needs and filling them, rather than making products and selling them. Putting the customers first is an easy concept to understand: it is fairly obvious that giving poor service or selling shoddy products will cause them to spend their money elsewhere, but the concept is difficult to apply in practice. For example, few firms keep the best spaces in the car park free for customers – these are usually reserved for senior management. Likewise, firms typically express their annual results in financial terms (for the benefit of the shareholders) rather than discussing customer satisfaction ratings, customer retention levels, and so forth.

Narver and Slater (1990) identified three components that determine the degree to which a company is market-orientated: competitor orientation, customer orientation and inter-functional co-ordination. For these authors, customer orientation is the degree to which the organisation understands its customers. The better the understanding, the better the firm is able to create value for the customers.

Understanding customers is, however, only the beginning. Customers can be seen to have generic needs: these are as follows:

• Current product needs. All customers for a given product have needs based on the product features and benefits. They may also have similar needs in terms of the quantity of product they buy, and any problems they might face in using the product (for example, complex equipment such as GPS units may need specialised instruction manuals).

• Future needs. Predicting future needs of existing customers is a key element in customer orientation. Typically, this is a function of marketing research, but part of the customer centrality concept is that we should not tire out our customers by constantly asking them questions – some people resent being asked about their future needs, even though the firm might only be trying to be helpful.

• Desired pricing levels. Customers naturally want to buy products at the lowest possible prices, but pricing is far from straightforward for marketers. Customers will only pay what they think is reasonable for a product, and obviously firms can only supply products at a profit (at least in the long term). Customers will only pay what they perceive as a ‘fair’ price (based on what they believe to be the benefits of owning the product), but equally, price is a signal of quality: people naturally assume that a higher-priced product represents better quality. Thus cutting prices might be counter-productive, since it signals that the product is of lower quality.

• Information needs. Customers need to know about a product, and about the implications of owning it: this includes the drawbacks as well as the advantages. In most cases, companies are unlikely to flag up the drawbacks (except regarding unsafe use of the product) but customers will still seek out this information, perhaps from other purchasers and users of the product. Information therefore needs to be presented in an appropriate place and format, and should be accurate.

• Product availability. Products need to be available in the right place at the right time. This means that the firm needs to recruit the appropriate intermediaries (wholesalers, retailers, agents and so forth) to ensure that the product can be found in the place the customer expects to find it.

The above needs are generic to all customers, whether they are commercial customers, consumers, people buying on behalf of family or friends, or even organisational buyers.

The concept of customer centrality is not easy to apply within firms, because managers have to balance the needs of other groups of stakeholders. Company directors have a legal responsibility to put shareholders’ interests ahead of any other consideration, personnel managers have a responsibility to meet the needs of employees, and so forth. The main difficulty (and one which eludes many marketers) is the reasoning behind customer centrality. Some marketers tend to believe that meeting customer needs effectively is an end in itself, whereas others see it as instrumental in persuading customers to part with their money. This is by no means an abstract difference of view – marketers taking the former view will tend to think of all customers as being worthy of attention, whether they are profitable customers or not, whereas those adhering to the second viewpoint will take a much more cynical view, perhaps appearing to seek to exploit customers. For example, Sir Alan Sugar (the hard-nosed London entrepreneur who built the Amstrad consumer electronics business up from nothing within a few years) is famous for saying ‘Pan Am takes good care of you. Marks & Spencer loves you. Securicor cares. At Amstrad, we want your money’ (Financial Times 1987).

Although Sugar’s statement was perhaps somewhat tongue-in-cheek, it does sum up the underlying attitude of many company directors. In this view of the world, the purpose of meeting customer needs is to ensure that customers are still prepared to hand over their money in exchange for value received – a concept that has not eluded Sugar, whose products always represent good value for money.

In 2000 Peter Doyle published a seminal book entitled Value-Based Marketing in which he critiqued the idea of customer centrality. The aim of the book was to redefine the role of marketing and clarify how its success (or otherwise) should be measured. His argument was that marketing has not been integrated with the modern concept of value creation: it is still caught up in the profit-making paradigm, which is not actually what companies do: in the main, companies are focused on maximising shareholder value.

Doyle gave numerous examples of companies that had succeeded not through exceptional consumer value, but through creating and providing exceptional value to other stakeholders. He pointed out that only 12 chief executives of the UK’s top 100 companies had any marketing experience, and 43% of UK companies had no marketing representation on their board of directors. Doyle attributes this to a failure of marketers to take on board the concept of shareholder value, which is (in general) the main preoccupation of boards of directors. In fact, Doyle regards this as the primary obligation of directors. This leads on to the idea that marketing is, in fact, a means to an end: providing customer value is only a stage in the process of increasing shareholder value.

In the final analysis, customer centrality is an easy (even obvious) concept, but the practical difficulties of implementing it are immense. Marketers will, in the meantime, continue to advocate the idea that customer need should be foremost in corporate thinking, and company directors will continue to regard customers as only one stakeholder group. Probably the directors are right – but even if this is the case, customers are the only stakeholder group that provides the income the company needs to fund all the other stakeholders. That being the case, other stakeholders need to consider what they are offering which will facilitate the exchanges with customers on which the company relies.

See also: relationship marketing, consumerism, the whole of Part 3

REFERENCES

Doyle, P. (2000) Value-Based Marketing. Chichester: John Wiley.

Financial Times (1987) Also reported in The Observer (3 May 1987) ‘Sayings of the week’.

Narver, J.C. and Slater, S.F. (1990) ‘The effects of a market orientation on business profitability’, Journal of Marketing, 54 (Oct): 20–55.

![]()

Management of Exchange

Management of exchange is the theory that marketing is concerned with influencing and controlling the transfer of value between buyers and sellers.

The view of marketing as the management of exchange is usually associated with Philip Kotler, who defines marketing as follows:

In fact, the exchange view of marketing was first proposed by Wroe Alderson (1957), and is based on the assumption that both parties want what the other one has, and are both prepared to exchange.

Exchange as a means of obtaining what one wants goes back to prehistory. Even before formalised trading was invented we can assume that early people exchanged surpluses of one thing for other things they needed. In the Lake District region of the UK a prehistoric factory for making hand axes was discovered in the 1960s: axes made from Lakeland stone have been found as far away as the South of France, so fairly obviously a flourishing trade of some sort existed during the Stone Age.

Economists have developed theories of exchange which seek to explain the process and motivations of those involved. The key concept is that of the indifference curve, which illustrates the degree to which someone is prepared to accept a surplus of one item in exchange for another.

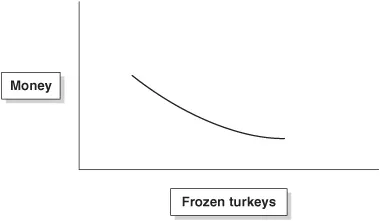

An indifference curve assumes that an individual has a trade-off between different items in his or her portfolio of wealth. For example, most people have a store of food in their houses, and a store of money in the bank. Up to a point, it does not matter much if one spends some of the money (reducing the store of cash) in order to increases the store of food, but as the imbalance grows the level of food that needs to be bought to compensate for the reduction in savings will have to increase. In other words, if the freezer is already full, the consumer would have to see a really irresistible bargain in frozen turkeys in order to make the purchase. The same is true in the other direction – if food stocks go too low, the individual will certainly spend a portion of his or her savings to restock the larder, and the bank would have to offer an extremely high interest rate to prevent this happening. An indifference curve which illustrates this is shown in Figure 1.1. Note that the curve ends before it reaches the limit – this is because the individual will have a cut-off point, not wishing to have no money at all but plenty of food, or no stocks of food but plenty of money.

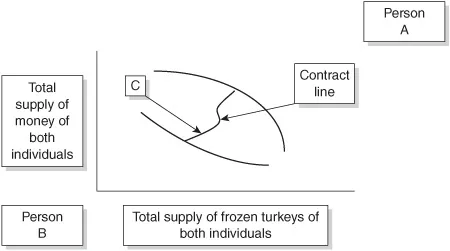

If we consider a simple case of two individuals, each of whom has a supply of food and a supply of money, we can map the total supply of food and money as shown in Figure 1.2. Here, Person A and Person B are each indifferent as to how much food or money they have, provided the totals fall somewhere along the indifference curve. However, it is possible to consider Point C, which is a point at which the total amount of food and money could be divided between the two people, but which lies above each of their indifference curves. This means that both are actually better off in terms of both food and money. Point C is on the contract line, which is a line along which either party would be better off. Note that the nearer Point C is to an individual’s indifference curve, the better off the other individual will be, so the actual point at which the exchange is made will depend on the negotiating skills or power relationships of the parties. In the diagram, Person B is obviously not as skilled a bargainer as Person A. This model was first proposed by Edgeworth (1881) and refined by Pareto in 1906, so it considerably predates either Wroe Alderson or Philip Kotler.

Figure 1.1 Indifference curve

Figure 1.2 Edgeworth Box

At first, it appears counter-intuitive that an exchange results in both parties being better off in terms of both money and turkeys. This apparent anomaly comes about because each individual has a different view of the relative values of food and money. This is clearly the case if the individuals are, respectively, a grocer and a consumer. The grocer would rather have the money than have the food, since he or she has more than enough food for personal use, whereas the consumer would clearly prefer to have the food rather than the money. This concept is important because it negates the idea that market value is fixed. All values are subjective, and depend on the perceptions and situation of the individual.

Broadly then, trade is always good and exchanges always result in both parties being better off (except in the case of deliberate fraud, of course). This is why governments worldwide try to reduce trade barriers: the more we trade with other countries, the better off we become.

Returning to Kotler’s definition of marketing, there is a problem in that it tries to include all human exchange processes, and does not differentiate between the buyer and the seller. This makes the definition very broad, which means that it is difficult to identify what is marketing and what is not (presumably this is what a definition sets out to do). For example, Kotler is apparently arguing that a parent who agrees to take a child to the cinema in exchange for tidying his room is engaging in marketing, and even that the child is also engaging in marketing. This would seem somewhat peculiar to most people.

A further criticism of the marketing-as-exchange-management model is that it does not allow for non-profit marketing, unless one is prepared to stretch a few points intellectually. If a government anti-drinking campaign uses a series of TV advertisements to discourage people from overindulging, this is clearly marketing (within the non-profit marketing paradigm). However, it is difficult to see where the exchange part of the equation comes in. Is someone who heeds the advertising and reduces his or her drinking actually giving the government something in exchange for the advertising? And what (if anything) is the exchange being offered?

Undoubtedly marketing involves the management of exchange as part of what it does. Managing exchange is not the whole of marketing, though, nor do all exchanges fit under the marketing umbrella.

See also: quality, the whole of Part 2

REFERENCES

Alderson, W.C. (1957) Marketing Behaviour and Executive Action: A Functionalist Approach to Marketing. Homewood, IL: Irwin.

Edgeworth, F.Y. (1881) Mathematical Psychics. Kegan Paul.

Kotler, P., Armstrong, J., Saunders, J. and Wong, V. (2003) Principles of Marketing. Harlow: FT Prentice Hall.

Pareto, V. Manual of Political Economy. London: Macmillan.

![]()

Evol...