1

“Just Us”

African American Humor in Multiethnic America

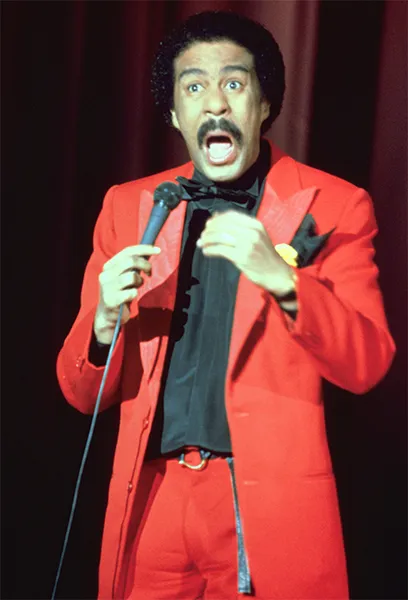

On his 1975 Grammy-winning comedy album, . . . Is It Something I Said?, Richard Pryor comments on the disproportionate number of African Americans in prison: “You go down there looking for justice,” Pryor quips, “and that’s what you find: just us.”1 The joke itself is a fairly simple pun addressing racial inequality in the American justice system, but it also speaks to Pryor’s position (and by extension, the position of African American humor in general) in American culture. The “us” of Pryor’s joke of course refers to African Americans. By this point in his career, however, Pryor was already a crossover comedian, and his audiences were racially mixed. In fact, Pryor is generally credited with bringing genuine African American folk humor to the attention of mainstream white audiences. According to Mel Watkins, Pryor “was the first African-American stand-up comedian to speak candidly and successfully to integrated audiences the way black people joked among themselves.”2 Given the heterogeneous racial makeup of his fans, Pryor’s “just us” strategically excluded a large portion of his live audience and probably an even larger portion of the listeners who bought his albums. Ironically, this exclusion only increased Pryor’s popularity with white audiences. In a cultural landscape where blackness itself is a commodity, the rhetorical exclusion of whites most likely served to make white audience members feel as if they were “down” with black culture. Siva Vaidhyanathan addresses this phenomenon, suggesting that if “white audience members got more than half the jokes at a Pryor concert, they could feel included. . . . White America desired an avenue into black oral tradition, and Pryor offered it on a large scale.”3

Pryor’s comedy was therefore a delicate balancing act between an authentically black “just us” aesthetic and mainstream crossover appeal. Even as whites flocked to his shows and purchased his albums in droves, Pryor used various rhetorical strategies, such as his “just us” joke, to delineate his performances as a black space. One of the most famous of these strategies is the comic comparison between white and black cultures. For example, in his most famous performance, the 1979 film Richard Pryor: Live in Concert, Pryor opens by joking about whites in the audience who, upon returning from the bathroom, find that blacks have taken their seats. Pryor uses this scenario to launch into an extended critique of white culture, in which he skillfully impersonates a series of nervous, uptight, and decidedly unhip white characters and contrasts them with looser, more relaxed, and cooler African American voices. Pryor, for example, impersonates a black man walking through the woods who, thanks to his natural rhythm, dodges a poisonous snake. An oblivious white man on a similar hike is not so attuned to Mother Nature and inevitably gets bitten. These sorts of black/white comparisons have since become staples of contemporary American humor. Indeed, the specter of Pryor’s “just us” aesthetic, as well as his black/white comparisons, presides over the history of African American humor since the 1970s, and it provides a salient example of Werner Sollors’s assertion that ethnic humor “is a form of boundary construction.”4

A large portion of post-Pryor African American humor, however, has kept Pryor’s comic attitude, especially his “blue” language, but lost his subversive edge. And very often, any progressive critiques in the realm of race relations are undermined by a regressive gender politics. This is seen most clearly in the early work of Pryor’s heir apparent, at least in terms of mass appeal, Eddie Murphy. Murphy does occasionally critique American race relations, especially in his Saturday Night Live sketch “White Like Me,” in which Murphy dons whiteface in order to learn the true nature of “white America,” but his stand-up is often driven by homophobia and misogyny. Bambi Haggins asserts that Murphy’s stand-up “reaffirms [the status quo] by reasserting black masculinity through the degradation of black women (and women in general) and annunciating the beginnings of a backlash against feminism.”5 For Haggins, the most disturbing aspect of this conservative gender politics is the way that it has been “embraced by the male and female comics of the Def Jam generation.”6 Indeed, there is little difference in the conservative visions of gender espoused in the Def Comedy Jam–inspired The Original Kings of Comedy (2000) or its 2001 female spin-off The Queens of Comedy.

Contemporary African American humorists, male and female, are more nuanced in their discussion of race than of gender, but even here the humor is most often driven by a traditional black/white vision of American ethnicity, in which humorists give scant attention to other ethnic groups. Despite growing numbers of Latinos, Asian Americans, and Arab Americans, most black comedians maintain a “just us” worldview. This is not to suggest that African American humorists never make jokes about Latinos or Asian Americans; they often do. Most of the time, however, this humor is fleeting and broad. Jokes about other ethnic positions rarely receive the sustained scrutiny that African American comics reserve for black/white race relations. In her stand-up special I’ma Be Me (2009), for example, Wanda Sykes provides a short routine about how a Mexican man can go anywhere as long as he is carrying a leaf blower. The jokes suggests the ways in which Latino laborers often remain invisible to mainstream America, but Sykes—who in the same act provides very insightful discussions of race and sexuality—offers little commentary past the initial observation. A more startling example can be found in the late Patrice O’Neal’s assertion, in his Comedy Central Presents special, that Asian and Arab groups need to “pick a color” because it is too difficult for outsiders to understand their ethnic backgrounds.7 The joke displays a strict adherence to the black/white racial lens. Some of the most sophisticated black comedians, like Chris Rock and Paul Mooney, address America’s multiethnic demographic at more length, but even they do so in a way that ultimately reinforces the white/black binary and avoids discussions of the relationships between African Americans and other nonwhite groups. In contrast to this majority of African American humorists, Dave Chappelle has offered an in-depth exploration of African American culture in relation to multiethnic America. Chappelle’s humor does not propose a consistent ethnic ideology, but it does suggest that a rigid “just us” aesthetic is no longer tenable for a full exploration of African American life and culture.

African American Humor and Black Communal Space

Making humor out of the black/white divide, of course, goes back much further than Pryor. At the turn of the twentieth century, W.E.B. Du Bois articulated his well-known theory of “double consciousness” to explain the struggle of the African American: “One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body.”8 Watkins asserts that “Du Bois’s eloquent description of African America’s psychological predicament provides a salient clue to the source and special tenor of black American humor.”9 He goes on to explain that from the time of slavery until the civil rights movement, this double consciousness manifested itself in “a dual mode of behavior and expression—one for whites and another for themselves.”10 A prime example of this “dual mode of behavior” can be found in the oft-quoted African American folk saying, “Got one mind for white folk to see / ’Nother for what I know is me.”11 This imposed dichotomous worldview fostered the type of comparative black-versus-white humor that is a staple for black comics, and it simultaneously created the need for black communal spaces in which African Americans could express their criticisms of the dominant culture freely. Christine Acham explains the genesis of such communal spaces, arguing that this sort of boundary construction was

dictated by law from the days of slavery, through slave codes, the black codes in the post-Reconstruction era, and eventually Jim Crow laws, which enforced segregation. However, considering the antagonistic and destructive atmosphere created by the enslavement of black people and the cultural differences in American society, we need not wonder why reprieve was to be found within these black communal sites. It was here that many black people found a sense of self-affirmation. They garnered the strength to cope with the harsh reality of their public life and critiqued the white society that enslaved them and refused to acknowledge their status as human beings. They also celebrated, relaxed, and enjoyed themselves away from the critical eyes of white society.12

Black communal spaces were essential to African American humor as forums where it could be practiced, but over time, the spaces themselves became necessary components of the humor, part of its content. Thus in her book of folklore Mules and Men (1935), Zora Neale Hurston not only relates a series of often humorous African American folk tales, but she also painstakingly re-creates the front-porch setting in which the stories are told. Pryor and other late-twentieth-century black comics attempt to maintain the black communal aspects of this front-porch culture, but by doing so, black communal culture itself has become increasingly commodified and attractive to nonblack audiences. In recent years, the marketability of black communal culture has become increasingly apparent. Extreme examples are the Barbershop films (2002 and 2004) and the spin-off film Beauty Shop (2005), which celebrate the spaces named as being more than businesses but as community centers where African Americans can relax, talk, and joke. Similar examples can be found in the series of Friday films and in the seemingly never-ending stream of Tyler Perry vehicles.

Despite their mainstream appeal, these works use various rhetorical devices to maintain a semblance of communal black culture. Like Pryor’s “just us” joke, black humorists repeatedly suggest that while white audiences are free to listen in—especially if they are willing to pay the cost of a ticket—the humor itself, and the spaces in which it is performed, are the cultural property of African Americans. This is extremely evident in a stand-up series such as HBO’s Def Comedy Jam, produced by media mogul Russell Simmons. The series establishes itself as not only a comedy show but also as a black communal space. Def Comedy Jam helped launch the careers of dozens of successful African American comics, including Dave Chappelle, Chris Rock, Bernie Mac, Cedric the Entertainer, Martin Lawrence, and D. L. Hughley. Each episode features an emcee who playfully banters with the small studio audience before introducing the individual comics, thus establishing a relaxed and intimate atmosphere. Like Pryor, more than twenty years before them, the emcees and comics often make a point of singling out white audience members. By demonstrating white spectators as an anomaly, the show further establishes itself as a black space.

Spike Lee’s concert documentary The Original Kings of Comedy is another important and extremely influential work of African American humor that deliberately creates a black space. The film records the acts of four Def Comedy Jam veterans—Steve Harvey, D. L. Hughley, Cedric the Entertainer, and the late Bernie Mac—for a primarily black audience in Charlotte, North Carolina. It also takes great pains to demonstrate that the live show is an African American community event. The comedy itself continues the “just us” tradition of African American humor: the comics make good-natured, self-deprecating jokes about perceived idiosyncrasies within black culture, and they offer a series of comic critiques of whites. Steve Harvey, for example, describes what the film Titanic would have been like if it had been about black people, and D. L. Hughley jokes about white people’s love for extreme sports, asserting that bungee jumping is “too much like lynching” for him. Cedric the Entertainer repeats almost verbatim Pryor’s joke about white audience members having their seats taken by blacks. The humor in the film is thus fairly conventional and offers exactly what audience members have come to expect from African American comedians. However, The Original Kings of Comedy is noteworthy in the way that it emphasizes the concert’s black communal aspects. Steve Harvey, acting as master of ceremonies, leads the audience in a sing along to a series of classic R&B songs. In the film, the editing drives home the black communal aspects as the camera pans wide and shows a large auditorium full of primarily African American audience members dancing and singing together. Spike Lee’s direction further highlights the importance of the concert for the black community by frequently cutting from the comedian performing to a shot of the audience’s reaction. The visual rhetoric reinforces the black/white binary that is created by the humor itself: it includes black viewers while excluding whites.

Def Comedy Jam and The Original Kings of Comedy both succeed at creating black performance venues that continue the tradition of a communal African American folk humor. They are both, however, ultimately reductive in the ways that they represent and/or critique race relations in present-day America. By relying on a primarily black/white worldview, these works overlook contemporary changes in the American population and offer little consideration of how other ethnic groups, especially Latinos and Asian Americans, influence and are influenced by black culture. Ironically, despite its insularity, The Original Kings has had an enormous impact on the landscape of contemporary ethnic American humor, for it has inspired a series of imitation comedy tours and films that are built around celebrating a specific ethnicity, such as The Original Latin Kings of Comedy (2002) and The Kims of Comedy (2005).13

These various ethnocentric comedy programs suggest a pluralist model of contemporary American humor, which bears a striking resemblance to the fixed and rigid boundaries of David Hollinger’s ethno-racial pentagon, discussed in the introduction to this book. In this model, each ethnic group has its own comedians and its own ethnic stereotypes to either overturn or self-deprecatingly reinforce. People of other ethnicities are free to watch as well, but it is understood that the comedy is not for them and that they will not fully “get” it. This comedy relies on what Paul Gilroy describes as an “emphasis on culture as a form of property to be owned.”14 This comic landscape further suggests that not only do many African Americans police their ethnic boundaries with anxiety but that they do so in ways that serve as a model for other ethnic groups. The influence of African American humor on the humor of other ethnic affiliations is in line with the ways that race in America is traditionally constructed. Gary Segura and Helena Alves Rodrigues note that “scholarly understandings of race and its consequences for American politics have been achieved largely through the analytic lens of a black-white dynamic. . . . When discussions move beyond these groups, political scientists often mistakenly presume that arguments and findings with respect to African-Americans extend to other racial and ethnic groups. Moreover, racial and ethnic interactions between Anglos and other minority groups are assumed to mimic—to some degree—the black-white experience.”15 The actual ethnic landscape in America is of course significantly more complex and consists of a tangled web of multiethnic cooperation, conflict, anxiety, and influence. For instance, most studies seem to indicate that blacks feel somewhat threatened by the increasing numbers of other minority groups (especially Latinos) and the claims that they might make on jobs and resources that would otherwise help black communities.

According to Hollinger, these feelings of anxiety are well-founded. He explains that when the African American experience is used as a lens through which to understand all nonwhite groups, that nonblack minorities often end up benefiting from resources that were intended as reparations for the specific history of black enslavement and segregation.16 There is not necessarily a direct connection between such concerns and the insular nature of most African American humor, but the fact that many African Americans are aware of these issues may help explain the reluctance of contemporary black comics to discuss the relationships between African Americans and other nonwhite groups. The rigidly delineated humor of Def Comedy Jam and The Original Kings of Comedy, however, does not represent the entire range of African American humor. There are contemporary black humorists who display more willingness to explore blackness in a larger multiethnic context, and discussions of this sort may illuminate more fully the complex relationships between African Americans and other groups. Paul Mooney and Chris Rock, for example, occasionally discuss African American culture in relation to other ethnicities, but they do so in a manner that ultimately reinforces a traditional “just us” black comic aesthetic.

Mooney and Rock: Enforcing the Binary

African American humorist Paul Mooney has spent most of his career relatively unknown by mainstream audiences and ignored by humor scholars. In his foreword to Mooney’s memoir, Black Is the New White (2010), Dave Chappelle addresses this obscurity, arguing that Mooney is “too black for Hollywood!”17 Despite his lack of fame, Mooney has been a constant presence in African American humor for the past forty years. He was a writer for, and close friend of, Richard Pryor, and he served as head writer for Pryor’s short-lived variety program The Richard Pryor Show (1977). With Pryor, he also wrote occasionally for Norman Lear’s sitcom Sanford and Son (1972–1977).18 In the 1990s, Mooney worked as a writer for the African American–centered sketch comedy show In Living Color (1990–1994), where he created one of the series’s most popular characters, the angry black children’s entertainer, Homey D. Clown, portrayed on the show by Damon Wayans.19 In the twenty-first century, Mooney worked as a writer for, and appeared in various sketches on, Chappelle’s Show. Mooney has also had an active and prolific stand-up career, having produced two comedy albums and three concert films. His résumé shows he has been a major part of African American humor since it became mainstream in the 1970s. A consideration of Mooney’s work can thus be useful in tracking the history of African American humor. As part of this history, Mooney, even more so than Pryor and the Def Comedy Jam comics, fiercely enforces a “just us” comic aesthetic. In fact, on the liner notes to . . . Is It Something I Said?, Pryor claims to have stolen the “just us” joke from Mooney.

Mooney’s humor is a mixture of indignation and racial pride and, when it is unmitigated b...