![]()

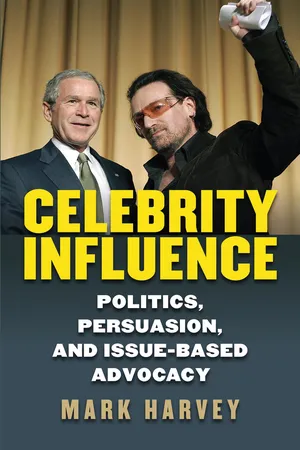

1. The President Meets the Rock Star

“George Bush is a comedian. . . . I walk down the corridor, he comes out and stands to attention. ‘Here’s the President. . . . What do you want us to do this time, Bono?’”

This is Bono, lead singer of the rock group U2, talking about a private exchange with President George W. Bush at the 2005 G8 summit in Gleneagles, Scotland. According to Bono, the president humorously stood at attention, as if he were at the beck and call of the rock star.

At the G8 summit, Bono had a free access “backstage pass,” which allowed him to lobby President Bush and other world leaders to sign a communiqué pledging $50 billion of debt relief to some of the poorest countries in the world. “Now this is a guy who knows where I stand on the [Iraq] war,” Bono continues, “a long, long way from where he stands—who knows there are so many things we could never see eye to eye on, and yet the leader of the free world lets us into the room and we’re there for an hour, shaking the tree at the last minute, pushing malaria and pushing girls’ education, making sure it ends up in the communiqué” (McCormick et al. 2006, 342).

What is a rock star doing at a gathering of the world’s most powerful political leaders, and why should anyone listen to him? Bono is not an elected official. The indebted countries he claims to represent are not paying him and did not choose him to be their spokesman. Bono and his organization did not donate cash to Bush’s reelection campaign. Bono’s main U.S. constituency, so to speak, consists of consumers of U2 records and concerts. Yet Bono gained rare access to some of the most powerful leaders in the world and persuaded them to sign a landmark document pledging a substantial sum. Bono’s story presents a modern puzzle: Why would the president of the United States give a rock star an hour of his time to lobby him directly on international debt relief? What does a celebrity have to offer a president?

Prior to 2016, this was a genuinely surprising question. Then, in a twist that seemed to emerge from the fictional political satire of films like Tim Robbins’s Bob Roberts or Warren Beatty’s Bullworth, a celebrity became president.1 Trump won. Donald J. Trump, a high-profile real estate developer and reality show star, was elected to the most powerful political position in the world. Trump did not win the Republican nomination or the presidency based on his resumé. He had no prior experience in military or public office. Indeed, more than any governor that ever ran an anti-Washington, anti-establishment campaign, Trump ran as the ultimate outsider. The fact that he was a celebrity instead of a politician became an asset rather than a liability. His only relevant experience was as a businessman, which he had promoted for years through tabloids and television. He brandished this experience as a qualification to improve the operations of government.

These facts make Trump rare but not unique. Outsiders with no political experience occasionally come onto the American scene to capitalize on voters’ disgust with the establishment. This populist approach has a certain mass appeal. Ross Perot, running in 1992 and less successfully in 1996, took a similar approach, promising to run the government like a business. What makes Trump unusual, according to Bill Schneider of Reuters (2015), is that he “combines two political traditions: the political outsider and the fringe candidate.” In addition to populist pronouncements, Trump also appeals to an extreme ideological core of Republicans centered in the Tea Party, who are very committed and motivated.

These factors alone do not necessarily prove his success, however. Many have argued that his bold campaign style may have made an important difference. Trump’s campaign events were like rock concerts. He was short on policy details and high on drama. People were as attracted to his insults as they were to his proposals. Indeed, he could utter the most offensive and outlandish statements, making outrageous promises and claims, and his popularity with his base would eventually rebound. Pundits expected disparaging statements about immigrants and a Mexican judge, a public altercation with the Muslim parents of an American soldier, disparaging comments about women and minorities, and revelations of a conversation in which he bragged about hypothetical sexual assault to derail his campaign. However, as Trump himself said at a rally in Iowa, “I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters” (Diamond 2016). What people expected from a campaign and a successful presidential candidate was ultimately turned on its head.

While it is correct that Trump has never held public office before, he has still been involved in politics, and his presidential run was years in the making. In 1987, at the encouragement of longtime Republican operative Roger Stone, Trump openly criticized Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy and hinted that he might run for president, ultimately landing in New Hampshire with an announcement that he would not do so (Kranish and Fisher 2016, 276). By the mid-1990s, his financial problems prevented his involvement in many political activities other than his routine support of political candidates as an ongoing cost of doing business. In 1999 he suggested that he might run for president for the Reform Party, naming Oprah Winfrey as a possible vice presidential choice. In 2000 he sought advice from Minnesota governor Jesse Ventura, but decided that he would not run and could not win as a third party candidate. Nevertheless, he won Reform Party primaries in Michigan and California (Kranish and Fisher 2016, 285–87).

Trump changed party identification seven times between 1999 and 2011 before contemplating a presidential run again. Trump’s resurgent celebrity, built upon his success as the star of the reality television show The Apprentice, made him a front-runner, tied for second behind former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney, and polling first among self-identified Tea Party voters. It was then that Trump began a grassroots campaign challenging President Barack Obama’s citizenship, alleging that he was born in Kenya rather than in the United States. While the political or media establishment never took these allegations too seriously, it was an interesting enough sideshow to make news. Trump would regularly tweet and show up on news shows to cast doubt on Obama’s citizenship and to demand “transparency.” Eventually Obama produced his long form birth certificate, announced that he had no time for this “silliness,” and then famously roasted Trump at the 2011 White House Correspondents’ Dinner. Two weeks later, Trump announced that he would not run for president and eventually endorsed Mitt Romney for president. Twelve days after Romney’s defeat, he patented the slogan “Make America Great Again” (Barbaro 2016; Kranish and Fisher 2016, 291–92; Parker and Eder 2016).

Despite Trump’s long-term ambition to be president, in some ways he has more in common with Bono than he does with Bush or Obama. Like Bono, he is a celebrity with no experience as a public official. Like Bono, he educated himself in political organizing through networking with political elites. Like Bono, he was really a political activist rather than a politician.

Indeed, outside of his successful presidential run—which one could argue more closely resembled a public advocacy campaign than a political campaign—his most successful political exercise was championing the birther movement. One could argue that it ended ignominiously, with Trump dropping his presidential aspirations after facing the ridicule of the White House Correspondents’ Dinner. However, he was extremely effective as a celebrity activist. He forced Obama to release his birth certificate. He likely had an effect on public opinion. In February 2011, one month before Trump weighed in on the birther issue, a CNN poll revealed that only 25 percent of Americans had doubts about Obama’s citizenship, and a PPP poll revealed that 51 percent of Republicans believed that Obama was not born in the United States. In March Trump first expressed his birther conspiracy beliefs on the daytime television show The View. Just before Obama released his birth certificate in April, a Gallup poll revealed that only 38 percent of all Americans were convinced that Obama was “definitely” born in the United States. After his birth certificate was released, that number improved to 47 percent. However, even as late as August 2016, an NBC poll revealed that 72 percent of Republicans believed that Obama was not born in the United States, and these results were consistent among both “high and low political knowledge Republicans” (Barbaro 2016; A. Barr 2011; Cheney 2016; Clinton and Roush 2016; Condon 2011; Parker and Eder 2016).

How much of Trump’s electoral success had to do with his celebrity status? During interviews conducted for research on this book, respondents were asked, “Is there something about Trump’s celebrity status that gave him an edge in the campaign? If so, what was it?” The following answers seem to reinforce much of the prior analysis:

“People had enough of the typical politician. Trump is different and talks like the average Joe.”

“He appealed to the individuals tired of politicians. His lack of filter seemed to make people feel he was real and more trustworthy than a politician. In addition, his appearance as a successful businessman elevated his status.”

“I believe uneducated Americans saw a familiar face they’d seen on television and decided to vote for him like it was American Idol.”

Perhaps too much should not be made of Trump’s success. After all, a majority of Americans voted for former secretary of state Hillary Clinton and her more conventional political campaign. According to some analyses, the number of votes in key districts that made a difference in Trump’s Electoral College victory could fill a small stadium (Meko, Lu, and Gamio 2016). Still, the very fact that a celebrity could mount a campaign to topple one of America’s most experienced political insiders is striking. Is there something that can be learned from stories like Trump’s? Are there dozens of potential “Donald Trumps”? Are there celebrities with enough fame, power, and skills to influence the political system? If so, how does this influence work?

SPEAKING OUT: LISTEN TO BATMAN

For every action, there must be a reaction. The ascendancy of celebrity Trump to the Republican nomination and ultimately the presidency has provoked an intense politicized reaction from his fellow celebrities. To name a few, producer Lee Daniels and many in the cast of his television show, Empire, criticized Trump for “violence and nasty rhetoric against mankind.” West Wing actor Richard Schiff charged, “We’ve never experienced anyone so blatantly willing to care so little about what happens to the world.” Actor Lena Dunham, speaking at the Democratic National Convention, said that Trump’s “rhetoric about women takes us back to a time when we were meant to be beautiful and silent.” America Ferrera, in another DNC speech, argued that “Donald’s not making America great again. He’s making America hate again.” Actor Susan Sarandon attacked Trump for making “hatred and racism normal” in America. Accepting her Golden Globe award in January 2017, actor Meryl Streep criticized Trump for mocking a disabled reporter in 2016: “This instinct to humiliate, when it’s modeled by someone in the public platform, by someone powerful, it filters down into everybody’s life, because it kind of gives permission for other people to do the same thing. Disrespect invites disrespect. Violence incites violence” (N. Brown 2017).

The Women’s March on Washington on January 21—the largest protest in American history—featured high-profile celebrities such as Janelle Monáe, Scarlett Johansson, Michael Moore, and Madonna speaking and performing on behalf of a multitude of liberal causes. Other celebrities took to the street and led chants, such as Katy Perry, Julia Roberts, Amy Poehler, Emma Watson, and Felicity Huffman. Countless other celebrities appeared at marches throughout the world that day, including Ian McKellen, Gillian Anderson, and Lin-Manuel Miranda in London (Garfield 2017; Izadi 2017). This celebrity activism was followed by political statements at the Golden Globes, Grammys, Film Independent Spirit Awards, and Oscar ceremonies from stars such as Jimmy Fallon, Hugh Laurie, Viola Davis, James Corden, Beyoncé, Katy Perry, Patton Oswalt, Casey Affleck, Jodi Foster, and Molly Shannon (E. Berman 2017; Del Barco 2017; Greenburg 2017; Konerman 2017). Singer and actor Jennifer Lopez summed up the general mood at the Grammy Awards: “At this particular time in history, our voices are needed more than ever” (Greenburg 2017).

“God help us,” sighed actor Robert De Niro (N. Brown 2017).

Even action star, former celebrity turned politician, and fellow Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger came out against Trump. Schwarzenegger succeeded Trump as the host of The Apprentice. In tweets and during a live presidential press conference, President Trump criticized Schwarzenegger for low ratings, calling the show a “total disaster.” Schwarzenegger’s first instinct was to “request a meeting and go back to New York. And then . . . just smash his face into the table.” Upon further reflection, he thought it better to “be above all of that and put him on the spot,” challenging Trump to “work for all of the American people as aggressively as you worked for your ratings” (Arnold Schwarzenegger on Trump 2017).

It is easy to argue that when celebrities speak, people listen. However, whether people pay much attention or care about political statements such as these is quite another question. A survey by CNN/USA Today said that only 3 percent of Americans believed that celebrities can be effective in influencing the political process or causes. Most (64 percent) believed that they were “not too effective or effective at all,” and 87 percent rejected the idea that celebrities influenced their personal positions on political issues (Gunter 2014, 145).

U.S. Olympic runner Nick Symmonds shares these sentiments. He argues that he and other athletes lack the credentials or ability to influence people, but that they have freedom of speech, just like any other citizen. In an interview expressing support for gun control and opposition to discrimination against homosexuals, he expresses his belief that he is obliged to speak his mind, even if it comes to nothing and even if his point of view provokes controversy:

Too often, athletes go into a press conference and are asked difficult questions and they say, “No comment,” and I never wanted to be that kind of athlete. I have opinions on everything and I have logical reasons why I have come to those conclusions and I’ll tell you why I feel that way. . . . They said, you know, you’re an athlete. What makes you qualified to speak out about anything? Or some people have gone as far as to say I’m a disgrace to America and I shouldn’t be allowed to represent the country because I can’t keep my mouth shut. And I just laugh at these people. . . . First Amendment is the right to free speech. And as an American, I’m going to exercise that right domestically and internationally, barring getting arrested in Russia for speaking out against their laws, where my First Amendment doesn’t necessarily apply (Ashlock 2013).

The public’s awkward, if not cynical, relationship with outspoken celebrities is nothing new. Singer Frank Sinatra supported Roosevelt for president in 1944, stating, “Some people tell me I may hurt my career by taking sides in a political campaign. And I say to them, ‘To hell with this career. Government is more important’” (Suebsaeng 2015).

Despite Symmonds’s self-professed humility about his personal views, few would care about his opinion if he were not an Olympic athlete. Likewise, Symmonds did not write an op-ed in Runner’s World or publicly dedicate “his silver medal to his gay and lesbian friends,” enduring criticism from cynics, if he did not hope or expect to change some minds (Symmonds 2013).

In contrast, actor Ben Affleck acknowledges society’s cynicism about celebrities and their causes, but he also claims to be far different from the typical American citizen. His aspirations are explicit. Appearing in a joint interview with Senator Russ Feingold on NPR’s Morning Edition with David Greene, Affleck claims:

I’m not an expert. I’m a person who’s spent a lot of energy and dedicated a lot of my time to this issue. . . . What I am is an advocate, and a human being, and a director, and an actor, and somebody who cares deeply about this, and wants other people to know about it. . . . We live in a society that gives a very, very high profile to even the most mundane activities of entertainers, and so I’d like to take some of that interest and focus it on something substantial (Greene 2014).

Affleck is right. Celebrities are not just typical American citizens. Few media consumers are interested in the real “mundane activities” of regular people.2 They want to hear from the next Batman. This may not be logical or rational. Indeed, it makes little sense to consult the next Batman on matters of public policy. Yet people do. And Affleck believes that he has something intelligent to share. Thus when Ben Affleck takes the microphone in an NPR studio, he believes that people will want to listen to Batman’s account of the civil war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. By appearing on a radio program, he hopes that Batman will be more likely than most experts to raise awareness and move people toward action on this issue.

Feingold and Greene seemed tacitly to concur. In the interview, 68 of the spoken words were Feingold’s, while 963 were Affleck’s. The interview was almost entirely directed toward Affleck, and Feingold did not attempt to intervene in the conversation. From this single example, one could infer that reporters and politicians alike may believe that people just wanted to listen to Batman—or that a celebrity is better at getting attention and making a case than a politician is.

I’M JUST A SINGER IN A ROCK AND ROLL BAND: GOOD INTENTIONS VERSUS REALITY

As mentioned before, there may be more in common between Trump and Bono than between Trump and Bush or Obama. However, Trump’s foray into celebrity activism was different from most of the celebrity activists profiled in this book. One could argue that Trump’s run for public office may have been an opportunity to serve his country and to “make America great again.” However, Trump sought political power. To the extent that he was able to exert celebrity influence, it was on behalf of his own electoral aspirations, not for a particular cause. Unlike Trump, the other celebrities profiled in this book have advocated on behalf of groups and political issues without seeking political office. Thus the motives are different. Trump wanted to gain political power to advance an agenda. The others intend to influence those in political power in order to advance an agenda.

This distinction is crucial. Trump did not have to “land lunches” with politicians to run for office. He could have done so. If, in 2015, he had convinced the establishment that he was a viable candidate and sought party support, some in the party would certainly have taken him seriously, and his presidential bid might have started more smoothly. Republicans have an interest in running a winning candidate. However, Trump did not want or need the attention of politicians. Part of the appeal of his campaign was to run against Washington in general and against the Republican Party establishment in particular. With his wealth and independence, he claimed to raise his own money and build his own organization, free from influence of the establishment. In Trump’s own ...