![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

There is no doubt in my mind that the RAF want very much to have the US Air Forces tarred with the morale bombing aftermath which we feel will be terrific.

—General Carl Spaatz1

If you want to overcome your enemy you must match your effort against his power of resistance, which can be expressed as the product of two inseparable factors, viz. the total means at his disposal and the strength of his will.

—Carl von Clausewitz2

Allied strategic bombing during World War II has generated considerable controversy among historians, regarding both results and motivations. Perhaps the most heated debate has focused on the intentional bombardment of civilians to break their morale, a practice called morale bombing or terror bombing. Basil Liddell Hart, the noted British military historian, called the practice of indiscriminate Allied area bombing of cities “the most uncivilized method of warfare the world has known since the Mongol devastations.” An American counterpart, Walter Millis, termed such tactics “unbridled savagery.”3 Many American historians, including me, have perceived a difference between the practices of the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the United States Army Air Forces (AAF), however, especially in the European theater. While the British embraced a policy of indiscriminate night area bombing as their only realistic option, the Americans pursued daylight aerial offensives against well-selected military and industrial targets that were justified by both “strategic judgment and morality.”4 Reflecting the Clausewitz quote above, the RAF targeted will, while the AAF aimed to destroy means.

During World War II, the United States Army Air Forces did enunciate a policy of pinpoint assaults on key industrial or military targets, avoiding indiscriminate attacks on population centers. This seems to differentiate US policy from the policies of Germany, Great Britain, and Japan, all of which resorted to intentional terror attacks on enemy cities during the war.5 Scholars who have cited the official AAF history emphasize the intention of American leaders to resist bombing noncombatants in Europe for both military and ethical reasons.6 Many of these writers contend that US airmen regarded civilian casualties as an unintentional and regrettable side effect of bombs dropped on military or industrial objectives; in contrast, the RAF campaign to destroy the cities themselves and kill or dislocate their inhabitants was a deliberate strategy.7

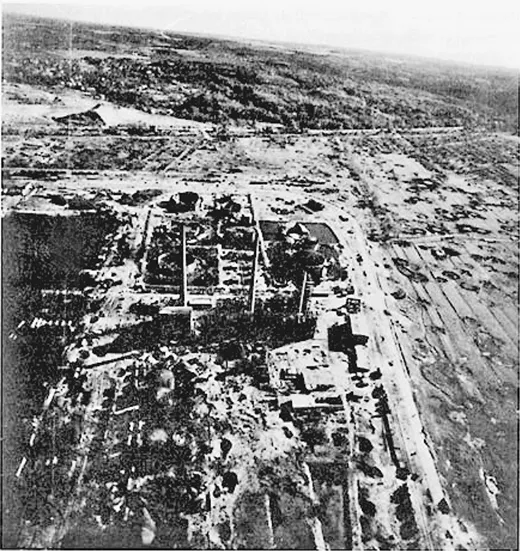

Two contrasting views of Allied strategic bombing of Germany in World War II: a section of Munich razed primarily by British night raids (above) and a destroyed oil refinery at Harburg hit by American daylight bombers (below). Note the many craters from near misses in the fields around the oil plant. (Northwest and Whitman College Archival Collections, Penrose Memorial Library, Whitman College, Walla Walla, WA)

A few British writers, such as Max Hastings, have for some time criticized the claimed ethical superiority of AAF strategic bombing as “moral hairsplitting.”8 Beginning in the 1980s, however, the tar of morale bombing that Spaatz feared was applied by American historians such as Ronald Schaffer and Michael Sherry. In a groundbreaking 1980 article, Schaffer analyzed the statements of AAF leaders as well as numerous wartime bombing documents in Europe and concluded that ethical codes “did little to discourage air attacks on German civilians.” In fact, “official policy against indiscriminate bombing was so broadly interpreted and so frequently breached as to become almost meaningless.” He argued that both the policy against terror bombing and ethical support for that policy among AAF leaders were “myths.” In his subsequent book, Wings of Judgment, which also discusses strategic bombing in the Pacific, Schaffer examined the issue in more detail. He softened his harsh judgment somewhat, but he still concluded that although “virtually every major figure concerned with American bombing expressed some views about the moral issue . . . moral constraints almost invariably bowed to what people described as military necessity,” another disputed concept.9

Sherry’s award-winning book focused on the development of American airpower, which ultimately led to the use of the atomic bomb. He concentrated on the bombing campaign against Japan and contended that strategists adopted the policy of indiscriminate firebombing of cities after precision bombing against military and industrial targets proved only marginally effective in 1944. Though racism made such tactics easier to adopt against Japan, firebombing was the inadvertent but inevitable product of an anonymous “technological fanaticism” of Allied bombing and airpower. The assumption that using everything available would lead to eventual victory was key in the decisions to firebomb and eventually to use the atomic bomb. The American press and public at the time accepted such measures as retribution for war crimes or as preparation for invasion. Since 1945, concerned Americans have focused on the decision to use the atomic bomb as “the moment of supreme moral choice”; Sherry argued that the whole bombing campaign was the product of “a slow accretion of large fears, thoughtless assumptions, and incremental decisions.”10

DOCTRINE, COMMAND AND CONTROL, AND OPERATIONS

Certainly AAF leaders had varying motivations and opinions about terror bombing. But a sophisticated understanding of military processes, particularly of doctrinal development, command and control, and operational execution, is needed to evaluate American strategic bombing. Both Schaffer and Sherry judged that the AAF failed to live up to the letter and spirit of precision-bombing doctrine. Sherry was especially critical because doctrine was not inspired and shaped to a greater degree by technology. Because of the limitations of the bombers of the 1930s, when precision bombing was developed, he argued, wartime technology was “more demonstrably than usual . . . the offspring, not the parent, of doctrine,” leading to vague and unrealistic assumptions about the potential of pinpoint strategic bombardment and diminishing utility and support of the doctrine as the war went on.11

Doctrine, however, is supposed to be developed to meet national goals, perform battlefield missions, or counter a perceived threat, and technology is then designed to implement the doctrine. Technological developments may force modifications in doctrine; ideally they should not drive it. Otherwise, the result is something like the Army’s infamous Sergeant York Air Defense Gun, an expensive piece of sophisticated equipment whose capabilities were shaped more by technological possibilities than by an accurate appraisal of the evolving threat of enemy aircraft.12 The entire family of US armor and antiarmor weapons in World War II illustrates the problem of allowing current technology to define tactical doctrine. Developed by technical experts to be light and mobile, American tanks and tank destroyers were employed to maximize mobility. However, they could not support the army’s overall strategy and doctrine of firepower and direct assault, which was required by the conditions of European combat. This flaw affected US ground operations throughout the war.13

Allowing current technology to define doctrine can also limit the scope of doctrine without providing guidance or flexibility for later developments. A study of the evolution of military doctrine in the three decades after World War II by the US Army’s Combat Studies Institute concludes that “the great value of doctrine is less the final answers it provides than the impetus it creates toward developing innovative and creative solutions” for future problems.14 The commander of the AAF, General Henry “Hap” Arnold, understood this process. In his final report to the secretary of war in 1945, he emphasized, “National safety would be endangered by an Air Force whose doctrines and techniques are tied solely to the equipment and processes of the moment.” The Air Force must keep “its doctrines ahead of its equipment, and its vision far into the future.”15 It is always better to have technology chasing doctrine, not the other way around.

It can be argued that the technology for precision bombing really did not exist until the smart bombs of the Vietnam War. The destruction of the French embassy during the 1986 air strike on Libya; the few televised misses with guided munitions and admitted poor accuracy with unguided weapons during DESERT STORM; the targeting of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in 1999; and the continuing debates over civilian casualties in Afghanistan and Iraq demonstrate that the ideal of pinpoint accuracy under all combat conditions has still not been reached.16 Yet the pursuit of accurate bombing remained a primary goal throughout World War II, influencing American tactics and technology during that conflict and setting precedents for later wars, including DESERT STORM, in which the US Air Force first provided an impressive demonstration of advances in precision methods and munitions in military briefings and media clips. When examined in comparison with the bombing results of other air forces in World War II, the intent, if not always the effect, of American air attacks was consistently to achieve the most precise and effective bombardment possible in pursuit of the destruction of the enemy’s capacity to resist in order to end the war as quickly as possible. Wartime improvements in bombing accuracy, as well as the eventual impact on the German economy, demonstrate that such a goal was realistic, not a dream always to be abandoned in favor of military expediency. Changing conditions influencing combat capabilities and effectiveness in the European and Pacific theaters did lead to the AAF’s acceptance of greater risks for enemy civilians by 1945, but in Europe at least, the operational record shows that the avoidance of noncombatant casualties in accordance with precision doctrine remained a component of American bombing, especially outside Germany, even if one of decreasing influence.

Military doctrine is simply a condensed expression of an accepted approach to campaigns, major operations, and battles. The general purposes of doctrine during and after World War II remained basically the same: “to provide guides for action or to suggest methods that would probably work best” and to facilitate communication between different elements by defining terms and providing concepts.17 Historically, American field commanders have felt free to interpret doctrinal guidance generally as they pleased. Indeed, the Soviets taught that “one of the serious problems in planning against American doctrine is that the Americans do not read their manuals nor do they feel any obligation to follow their doctrines.”18 This is certainly an exaggeration, but field commanders have rightly assumed that doctrine is basically a set of guidelines that permits much situational leeway. Traditionally, these same field commanders have been given considerable freedom from strict command and control, far in the rear. Even the official AAF history of World War II admits that “air force commanders actually enjoyed great latitude in waging the air war and sometimes paid scant attention” to directives from higher up.19

This means that the attitudes of leaders in Washington do not always determine operations in far-flung theaters of war. As Schaffer and Sherry pointed out, the leader in Washington most concerned about moral issues, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, was either ineffective or isolated. His position was basically administrative, and unlike the president or the chiefs of staff, he was not deeply involved in making strategy. Whatever their public pronouncements to the contrary, neither Roosevelt nor Arnold had any aversion to terror bombing when it suited their purposes. However, the extent of their control over commanders in the field should not be overstated. At times Arnold’s shifts in commanders had considerable influence on bombing policies, such as when he replaced Lieutenant General Ira Eaker with Major General Jimmy Doolittle and Brigadier General Haywood Hansell Jr. with Major General Curtis LeMay. In addition, Arnold’s consuming desire to justify an independent air service put pressure on AAF combat leaders to produce decisive bombing results. Yet whether because of distance, heart trouble, or the complexity of the war, Arnold rarely wielded a great deal of direct influence, especially in key operations late in the conflict. Sherry’s contention that he consistently exercised particularly strong direction of American strategic-bombing operations and units is not supported by the operational record.20

This loose doctrinal and command direction resulted in a bombing policy that was shaped by the operational and tactical commanders who actually dropped the bombs. To understand fully American strategic bombing, we must look at day-to-day planning and operations in the field, not just policy papers in the Pentagon. In his exemplary study of the escalating air war between Germany and Great Britain in 1940, F. M. Sallagar notes that “changes crept in as solutions to operational problems rather than as the consequences of considered policy decisions. In fact, they occurred almost independently of the formal decision making process.”21 In that case, the operational solutions always led toward terror bombing; the same is not true for the AAF. An examination of the actual execution of operations in Europe, such as CLARION, THUNDERCLAP, and the War-Weary Bomber project, reveals that American air commanders there consciously tried to avoid terror bombing even when superiors were encouraging it. Some, like Carl Spaatz, seemed to have genuine moral concerns about such bombing; others, like Ira Eaker, were apparently more concerned with public opinion against such tactics or believed they were ineffective or inefficient. AAF operations in Europe contrast starkly with the American strategic bombing of Japan, where the destruction of cities by firebombing was adopted. Yet this decision also was made by the commander on the scene, Curtis LeMay, without real direction from Washington. Bombing policy in each theater was shaped by the military necessity of combat, but it was also affected by the individual personality of each commander, who defined that necessity. Air campaigns were also influenced by command relationships. In Europe, US Strategic Air Forces (USSTAF) commander Spaatz worked closely with the theater commander, General Dwight Eisenhower, to synchronize air and ground operations. The Pacific theater had no such unified command or such a unified strategy. However, while strategic air operations against Japan were primarily conducted by the Twentieth Air Force, both the Eighth Air Force and the Fifteenth Air Force were bombing Germany, and they operated differe...