Chapter 1

The Crystallization of an Anti-Dutch Narrative

The triumphalist rendering of the city’s seventeenth-century history propagated by generations of Anglophiles has implanted an aura of inevitability around the transfer of New Amsterdam into English hands and the conversion of New Amsterdam’s burghers into Englishmen. Yet the English invasion of New Netherland in 1664, far from constituting a decisive change for Manhattan’s residents, inaugurated a prolonged stage in their history that was colored by uncertainty and trepidation. Between 1664 and 1674, urban dwellers witnessed three changes in government that were the byproduct of the ongoing rivalry between the Netherlands and England. In August 1664, New Netherland was seized by the English, only to revert to Dutch control between July 1673 and November 1674, at which time the colony was returned to English hands. New Amsterdam became New York City, which became New Orange, which again became New York City.1 Nor did the final change of sovereignty from the Dutch to the English in 1674 bring an enduring calm.

In 1688, three years after the colony’s proprietor, the Duke of York, became King James II, New York was incorporated into the Dominion of New England, a regional frame of government that diminished local authority and undercut the fragile moorings that had anchored residents’ lives. Mounting concern in England over James II’s Catholicism reverberated on the American side of the Atlantic. With the influx of persecuted French Protestants fleeing Louis XIV’s France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 putting a local face on the Catholic menace, Dutch New Yorkers were primed to defend their Protestant faith when they learned that James II had been ousted from the throne and replaced by William and Mary. Once Jacob Leisler, a Calvinist merchant, claimed the reins of government in the name of the new Protestant monarchs, the incipient divisions in the city came to the forefront as popular understandings of events in England, colored by a fierce attachment to Protestant values, clashed with the more Erastian views of the local elite. The subsequent suppression of Leisler and his followers by newly installed English officials, acting in concert with Leisler’s leading adversaries, failed to dampen the fervor of Leisler’s supporters and ushered in a generation of oppositional politics that suffused church life and social relations.

As rulers and rules kept changing, seventeenth-century New Yorkers were forced to define and redefine themselves in an era marked by indeterminacy. Alterations in government fostered instability, but the sense of contingency that pervaded the lives of city dwellers arose primarily from competing claims to cultural authority. In a society in which common denominators were in short supply, the absence of an overarching cultural framework to support debate and contain conflict left people of diverse cultural backgrounds struggling to coexist. Many former New Netherlanders continued to look at the world through a Dutch lens, unwilling to validate the culture of those who had seized their city. Newcomers from England entering this largely Dutch world oscillated between accommodation to Dutch customs and self-righteous assertions of Englishness. French refugees, ironically, found themselves in a position to shift the center of gravity in the city’s volatile political climate.

Historians of this tumultuous era in New York’s history have viewed the process of cultural change through the lens of politics, taking at face value the ethnic categories deployed by contemporaries. But these ethnic categories were invented and reinvented by political actors aiming to produce a version of history that would suit their partisan ends. The intensity of the anti-Catholic rhetoric employed by Jacob Leisler and his backers, who considered themselves above all good Protestants, leaves little doubt of their preference for sorting people according to their religious identities. By contrast, Leisler’s adversaries did not hesitate to brand his supporters as Dutch malcontents, and once they had gained the power to tell the story, they swiftly substituted ethnic for religious categories. Building an anti-Dutch narrative was the next step, as English authorities embarked on the cultural work necessary to subordinate city dwellers who, despite submitting to English rule, still considered themselves Dutch. In the wake of Leisler’s Rebellion, the English rulers of New York and their allies launched a multidimensional cultural offensive aimed at weakening the grip of Dutch culture on the city’s longtime residents. In the process, New York City’s Dutch culture was transformed from an alternative culture to an oppositional culture.

Mutability rather than permanence was the watchword of the years from 1664 to 1674 as both Dutch and English residents of Manhattan were forced to accommodate to “conquerors,” the Dutch doing so twice. Soon after the takeover, the ire of former New Netherlanders was aroused when soldiers from the English garrison “committed here within this City great insolences and insults towards divers Burghers and inhabitants.” Dutch townspeople, however offended, anticipated a quick reverse of military fortunes in the ongoing conflict between England and the United Provinces. In July 1665, Governor Richard Nicolls noted that “the Dutch here … have long hoped for and expected De Ruyter [a Dutch admiral].” Nicolls cautioned a subordinate at Albany not to be surprised at comments in this vein: “Let not your Eares bee abused with private Storyes, of the Dutch being disaffected to the English, for generally wee cannot expect they love us.” Elaborating on this theme in April 1666, Nicolls admitted that “at this present during the Warres with Holland we cannot expect the good affections of the Dutch here to the English.” Fear that the Dutch would ridicule them caused the city’s English rulers to conceal a shortage of money and goods. “We carry it on as well as we can, desiring not to let the people know that we are any way straightned; which to know, would cause some to rejoice, & insult.” The unease of English newcomers at the prospect of the Dutch recapturing New York was palpable. Encircled by unfriendly Dutch residents, they considered their position precarious and insisted that the governor remain to shield them. “The Towne & Country cry out they will leave their dwellings if they cannot stay mee from going to Boston,” Nicolls reported, “such are their apprehensions of a Dutch invasion” and the presumed retribution to be visited on them by the city’s Dutch population.2

Former New Amsterdammers did not cease to think of themselves as Dutch because they had acquiesced to English rule. In 1668, Domine (minister of the Dutch Reformed Church) Samuel Megapolensis complained that the manner in which his salary was collected—going around from house to house—was “unpleasant and degrading, and altogether unusual in our Dutch nation.” Megapolensis’s conviction that he was still a member of the “Dutch nation” was shared by former director-general Petrus (Peter) Stuyvesant, who in 1667 defined the new status of his colonial compatriots as “the Dutch nation (now his Royall High[n]esse most faithfull and obedient subjects).” Members of the city’s Common Council in a c. 1669 address to the Duke of York characterized themselves as “being for the most part Dutch borne (but now His Ma[jes]ties faithfull and loyal subjects)” and made a point of noting that the English government’s allowance of free trade with Holland “did encouradge most of ye dutch nation to remaine.” This notion of a hybrid identity—Dutch descent but English subject—seemingly was adopted by the King’s Council in London, which, in 1668, referred to “his Ma[jes]ties sworn subjects of the Dutch nation, inhabitants of New Yorke, in America.”3

Signs of amity between members of the two nations impressed one English official in 1669. “There is good correspondence kept between the English and Dutch, and to keep it the closer, sixteen (ten Dutch and 6 English) have had a constant meeting at each others houses in turnes, twice every week in winter, and now in summer once; they meet at six at night and part about eight or nine.” Dutch women and men marched side by side with their English counterparts in 1671 in the stately funeral procession for Governor Francis Lovelace’s nephew, signifying that the new rulers approved of parity between English and Dutch city dwellers. Lovelace was attentive to the needs of the local Dutch community, ordering the mayor to have a proclamation “publiquely read both in the English & Dutch Tongues…. and afterwards … affixed in the most publique places of the Citty” in 1668. In 1671, he empowered the elders and deacons of the city’s Dutch Reformed church “to make a Rate or Taxe amongst ye Inhabitants, and those that shall frequent ye Church” for the support of the minister, clerk, officers, and the poor, as well as the repair of the church building. In 1673, he endorsed the idea of “a Fast proposed by the Dutch Domine,” declaring that “noe particular but a Gen[er]all ffast shall bee Celebrated in this City.”4

Despite such fragmentary evidence of harmonious relations between Dutch and English, the appearance of a Dutch fleet in the vicinity of New York in July 1673 sparked a swell of patriotic feeling among former New Amsterdammers. Instantly, the residue of nearly a decade of English rule melted as the “Dutch in the Towne being all Armed Incouraged them [to a] storme,” and, as Captain John Manning, who was in charge during Governor Lovelace’s absence, recalled that “while they stormed ingaged that we should [not] look over our Workes and they were about 400 Armed Men.” Animated by feelings of loyalty to a fatherland some had never seen, the city’s many Dutch residents rejoiced at the prospect of the restoration of Dutch rule. The conflict now playing out in New York had erupted in Europe in 1672 when England, in company with France, had invaded the Netherlands. These hostilities soon had repercussions across the Atlantic, as a Dutch fleet sailing in American waters in 1673 seized on New York as a target of opportunity and recaptured the colony with virtually no resistance. The new Dutch rulers, acting in the name of the States General, revalidated the status of the Dutch residents of the city they dubbed New Orange. Those English who chose to remain in New Orange and retain their property were required to take a special oath to the States General of the United Provinces and the Prince of Orange.5

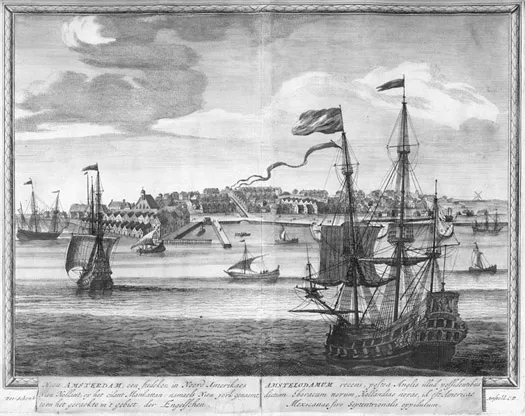

Figure 2. This view of New Amsterdam as it appeared in 1673 was incorporated into the mapmaker Peter Schenk’s Hecatompolis, published in Amsterdam in 1702. Courtesy of the Maps of Bert Twaalfhoven, from the Collections of Fordham University Libraries, Identifier FUNY-05194.

Yet there was no mistaking the precarious position of the reconquered colony. As New Orange’s burgomasters and schepens explained to the Dutch commanders on September 6, 1673, “Our enemies [the English and their French allies] by whom we … are encompassed round about on all sides … will doubtless endeavor … to reduce this place under England so soon as they hear that we are again left to ourselves; our weakness and condition being as well known to them as to ourselves since they have had now 9 years’ command over us.” Given the colony’s exposed position, it was not surprising that “some [have been] so bold as to say already that something else will again be seen before Christmas, and that the King of England will never suffer the Dutch to remain and sit down here in the centre of all his dominions to his serious prejudice in many respects, so that we are inevitably to expect a visit from our malevolent neighbors of old, now our bitter enemies unless they be prevented … by your valiant prowess and accompanying force.”6

The realities of imperial politics soon became evident. Whatever measures were taken by the province’s Dutch military rulers to avert attack by the English were in vain, as diplomats in Europe relinquished the fruits of the Dutch military venture as they negotiated the Treaty of Westminster, which ended the third (and final) Anglo-Dutch War in 1674. When Connecticut residents Isaac Melyn and John Sharpe, both of whom had ties to the city, made their way to New Orange in the spring of 1674 to spread the news of the colony’s restoration to English control in advance of official notification, the Dutch governor-general, Anthony Colve, had them placed in the dungeon of Fort William Henry. Melyn, a Dutchman, who spoke to “a multitude of his Countrymen” and inflamed their passions against the States General, was labeled an “unfaithfull Judasly and treacherous travaillor,” but he escaped execution after shifting blame to Sharpe, and instead was put to hard labor on the city’s defenses. Sharpe was banished from the city, his sentence being “Publisht … with great solemnity Ringing the Townehouse bell 3 tymes and the major part of the Towne congregated together” to witness it.7

Staging a spectacle that would deflect the burghers’ anger at their betrayal onto an out-of-place Englishman instead of the Dutch diplomats who had sealed the colony’s fate did not save the colony’s Dutch rulers from the vituperation of an enraged community when it became known that the territory had been ceded back to the English. Realizing that their welfare had been sacrificed to imperial goals, the city’s residents, in Sharpe’s words, “belch[ed] forth their curses and execration against the Prince of Orange and States of Holland, the Dutch Admiralls who tooke it, and their taskmaster the Governour.” They vowed not to “surrender, but keepe it by fighting soe long as they can stand with one Legg and fight with one hand.” Dismay at the outcome of an episode that had begun with high hopes of the resumption of Dutch rule prompted some burghers to sever their ties to the city when a second English takeover became imminent. “During the last four weeks,” the Dutch minister Wilhelmus Nieuwenhuisen wrote on July 26, 1674, “in apprehension of a change in governors, certain of our members have moved away.”8

Return to the Netherlands remained an option, but it did not become a reality for the great majority of local residents, whose long-standing ties to the community took precedence over feelings of attachment to patria. Yet the exacting terms of submission mandated by the new governor, Edmund Andros—specifically an oath requiring the populace to be prepared to take up arms in behalf of England against their fatherland—seemed too much to bear. Several wealthy Dutch merchants asked that they not to be “pressed to abjure all natural affection towards our own nation,” explaining that they “object[ed] to swearing lightly what nature and love for our own nation forbid.” Andros dealt with the recalcitrant merchants severely, confiscating their property, and even went so far as to imprison Nicholas Bayard, Petrus Stuyvesant’s nephew, to drive home the necessity of allegiance to the new English government. The governor’s draconian measures, “the unprecedented proceedings against the inhabitants in connection with the change in government,” had “excited the hatred and contempt of the rulers against the subjects.” Shaken by these events, many former residents of New Amsterdam were poised to uproot themselves from their longtime home. Domine Nieuwenhuisen confided that “I should not be surprised if a large portion of the Dutch citizens should be led to break up here and remove.”9

The ultimate submission of the contentious merchants not only established English authority definitively, but also paved the way for what turned out to be a cozy relationship between a Dutch-speaking governor, who had resided in the Netherlands during his youth, and merchants who had much to gain from accommodating to the new English regime. Andros would not budge on the issue of loyalty, but he was more than willing to offer lucrative opportunities to his Dutch friends, even to the point of alienating English merchants keen to carve out a niche in New York. English newcomers such as Anglican chaplain Charles Wooley, who served in New York between 1678 and 1680, believed that the local Dutch had been reconciled to English rule. He found the city’s “inhabitants, both English and Dutch very civil and courteous,” adding that “I cannot say that I observed any swearing or quarrelling, but was easily reconciled and recanted by a mild rebuke.” Imperial bureaucrat Edward Randolph also accented the harmony that prevailed in New York when Andros was governor. “I observed the English & Dutch lived very quiet, & in Freindship.”10

But the alliance forged between Andros and the Dutch elite caused ordinary Dutch residents to become suspicious of wealthy Dutch merchants such as Frederick Philipse who had become intimates of Andros. “He and the governor were one,” observed a Dutch visitor, presumably echoing the gossip of the streets. At a minimum, Dutch commoners still nurtured grudges against the English occupiers, a sentiment that surfaced in 1679 when members of the night watch were accused of beating Englishmen and yelling “Slay the English dogs.” Although Andr...