1

The Novel Truth

When I read [Peyton Place] at ten years old, I knew the world around me was a lie.

John Waters

In the autumn of 1956, Mrs. John L. Harris1 sat down to read Peyton Place, but her reading was fraught with difficulties. Her son, a student at Dartmouth College, “was disgusted,” she wrote its author, “and my husband wasn’t much better pleased.” Distracted and annoyed by the men in her family, the Seattle housewife nevertheless found the story “completely fascinating,” while the writing “caused me to fairly race through the pages.” Peyton Place’s critics had simply missed the point, she fumed. “The so-called ‘filth’ which many people censure in your book is to me only a small part of a truly good story.” Mrs. Harris urged Grace Metalious to carry on. “Please keep writing,” she implored. “Your talent is too good to hide.” Then she sat down to read Peyton Place a second time.

Mrs. Harris was hardly alone. “Finding nothing about to read on a dull evening,” Frank Allen picked up a copy of Peyton Place that someone had left behind at his New Hampshire summer camp. He had avoided reading the novel for almost three years after his favorite literary critic, Parker Marrow, panned it. “After a few pages,” Allen exclaimed in a letter to Metalious, “I whistled in astonishment and thought that so & so parker! he ought to be shot…. I have taken up cudgels in your defense ever since.” Even the harried cookery book writer Julia Child found in Peyton Place the perfect “reading-for-pure-self-indulgence.” Finding a copy in paperback a year after its publication, she recommended it to her friend Avis DeVoto. “Quite enjoyed it,” she confessed. Then, her vacation over, Child “soberly and happily” returned to Goethe.”2

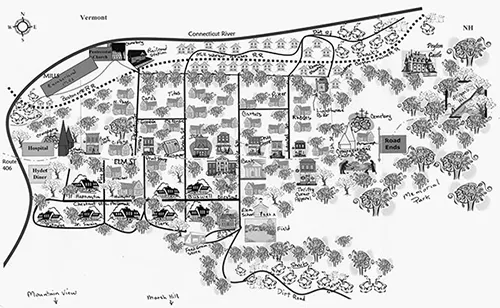

Figure 1. For some readers, Peyton Place was real enough to map. Map of Peyton Place by reader Deborah Briskey. Gift to the author.

Despite its reputation as a form of leisure, the reading of novels has never been a trouble-free activity, especially for women, whose readerly desires and habits have long been the subject of passionate concern and controversy. Almost from the first stirrings of the genre, the novel irritated people of quality. “Novels,” the Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush warned his readers, should be avoided at all costs, for rather than “soften[ing] the female heart into acts of humanity,” novels “blunt the heart to that which is real.” What made the new genre “novel,” in other words, was its focus on the imaginary and invented realms of human life, putting the novelist in tension with eighteenth-century calls to reason, evidence, and truth. Things only got worse. By the nineteenth century, fiction was jamming empiricist aspirations to objectivity and fact like dirt in a trigger. “History, travels, poetry, and moral essays” became, as Rush recommended, the preferred antidote to “that passion for reading novels which so generally prevails among the fair sex.”3

Republican mothers were no less vexed over the types of fiction that women readers preferred. Popular novelists like Hannah Webster Forster wrote extensively against the dangers inherent in certain books. She lamented “the kind of reading now adopted by the generality of young ladies,” which to her mind was “foreign to our manners.” Susanna Rowson worried as well that the reading of novels could “vitiate the taste and corrupt the heart,” joining Foster in decrying the ability of novels to promote among female readers “impure desires,” “vanity,” and “dissipation.”4

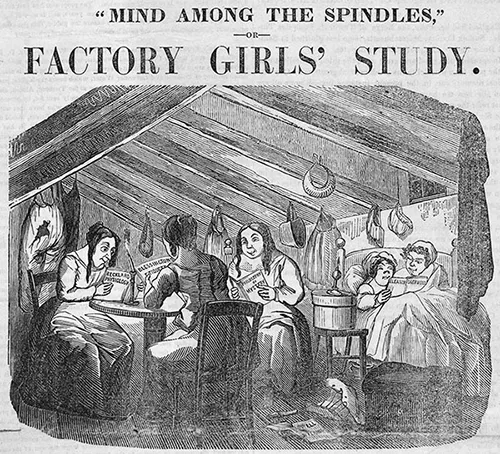

At the heart of these debates was the assumption, driven by Enlightenment concerns over the relationship between reason and passion, that fiction, especially romantic, gothic, and sensational novels, overly engaged the imagination of readers, making it difficult, if not impossible, for the untutored and “primitive” to distinguish between fact and fiction, fantasy and reality. Unlike the normative educated male reader, whose reasoning capacity, it was argued, provided a more critical rendering of such materials, female, working-class, and subjugated readers were said to lack the capacity to curb readerly flights of fancy. For them, novels reduced the rational self to the imitative behavior of the “captive audience,” whereby readers, too caught up in the thrills of fiction, forfeited their capacity to engage the narrative in a reasonable and productive manner. “For all of these lesser subjectivities,” scholars have made clear, “the exercise of the imagination was problematic.”5 The credulous reader could literally get lost in a book, so closely did she identify with character, plot, and scene. Even the sober mill girls of New England, it seems, fell under the sway of sensational reading, as newspaper cartoons like the one shown here invited readers to draw connections between cheap wages and cheap fiction at the very time when Lowell manufacturers were seeking to prove the moral as well as the monetary benefits of female wage labor. Nothing good, it seemed, could come from the irrational mental wanderings of fiction, for “novels not only pollute the imaginations of young women,” one American critic warned, but also give “false ideas of life.”6

Figure 2. Caricature of Lowell factory girls reading “cheap literature.” The woman on the left is reading a French sex manual, while the pair in bed share a racy novel by Joseph Holt Ingraham. “Factory Girls,” cover, Boston City Crier and Country Advertiser, April 1846. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

In the summer of 1905, Henry Dwight Sedgwick had had enough. Readers, he lamented, were nothing more than an indiscriminate “mob” rushing here and there in pursuit of the latest best-seller. “The proletariat, the lower bourgeois, and the upper bourgeois,” it mattered not at all, he wrote, for each class had abandoned its better instincts and training in quest of the “mob novel.” The numbers, Sedgwick reported, were shocking: “The Crisis, 405,000 copies sold, the Eternal City, 325,000, the Leopard’s Spots, with its career still before it, 94,000.” Like many of his literary brethren, Sedgwick worried over the state of American Letters and the nation that produced them. He explicitly linked the turbulent mass strikes that rocked his generation with the consumption of cheap novels and sensational stories, warning readers against the “Mob Spirit” that now engulfed Literature. In the grip of cheap fiction, he charged, the reader grew “more tumultuous, more passionate, more a creature of instinct and less a creature of reason.” The “reading mob the bigger it grows, becomes more emotional, more excited, it reads and talks with greater avidity, is increasingly vehement in its likes and dislikes, and opinions, forces the book on its neighbors, gives, and lends more and more with the swift and sure emotions of instinct.” Fiction had become a “contagion” spreading itself across the classes and undermining the educational efforts of schools and intellectuals.7

Sedgwick was born in 1861, seven years after the founding of the Boston Public Library, and his career as a lawyer, essayist, and historian paralleled the great boom in literacy and the mass marketing of books. Cheap paper put romance stories and dime novels into the hands of increasingly large numbers of working-class and immigrant readers, while free lending libraries not only expanded the reach of books but also gave local librarians the power to decide what kinds of books the public might check out. Publishers listened while library donors cringed. When Samuel Tilden learned that 90 percent of the books borrowed from the Boston Public Library were fiction, he came close to canceling his $2.4 million bequest to New Yorkers who hoped to establish their own free library. Literature, Sedgwick concluded, needed new leadership: “men of natural gifts and educated taste, experienced in the humanities,” who could “tame the turbulent mob spirit” as it coursed through the veins of American social and literary life. Literary men, that is, who shared his passion for Democracy and presumably the Atlantic Monthly. Bad novels made bad citizens.8

For those who sought to inflame the laboring mobs, cheap novels were blamed for making shoddy activists. Born in Russia, Rose Pastor came to the United States as a young girl of twelve and quickly found work in the cigar factories of Cleveland. Like Sedgwick, she was a “serious” reader, who turned her love of words into the literary arts, writing poetry and eventually advice columns for the Jewish Daily News in New York City. Moving to New York in 1903, she became active in the Socialist Party, writing on behalf of the working classes as an advocate of radical social change. Already popular among working girls on the Lower East Side, she became their heroine when she married the millionaire James Graham Phelps Stokes. Like Sedgwick, however, Pastor worried over the enormous popularity of cheap fiction and its effects on women and girls. Joining a growing chorus of progressive reformers and union leaders critical of working girls’ participation in consumer culture, especially their “frivolous” pursuit of fashion and romance novels, Pastor feared that dime novels would turn wage-earning women away from political struggle and working-class organization. As Nan Enstad notes, labor activists viewed stories that “offered a fantasy of magnificent wealth bestowed on the working-girl heroine through a secret inheritance and marriage to a millionaire” with condescension and suspicion.9 Serious times demanded serious books. “With our free circulating libraries,” Pastor scolded laboring women in 1903, “what excuse is there other than ignorance for any girl who reads the crazy phantasies from the imbecile brains of Laura Jean Libbey, The Duchess, and others of their ilk!…I appeal to you—if you read those books—stop! stop!”10

It was not to be. Pastor’s own marriage seemed the stuff of fantasy, her continuing radicalism living proof to readers of Laura Jean Libbey that fiction carried with it certain truths their own lives had yet to reveal, certain possibilities that might yet be played out. Readily available from pushcarts and newsstands throughout immigrant and working-class neighborhoods, dime novels joined pickles, bread, and eggs among the necessaries of daily life. But was Sedgwick right? Did cheap novels make for cheeky citizens?

Not surprisingly, proponents of women’s rights were there from the beginning, defending a woman’s right to read whatever her heart desired, more or less. But the relationship between fiction, fantasy, and femininity raised for feminists as well a number of troubling questions. Could the reading of gothic, romantic, and sensational novels, Mary Wollstonecraft and Jane Austen famously wondered, turn the female reader into the degraded “object of desire,” leading to a “conventional, dependent, and degenerate femininity”?11 Echoing Rose Pastor’s fears, Betty Friedan saw in the “sex glutted novels” of the post–World War II era a serious erosion of “independent activity” among American women which forced them to find “their sole fulfillment through their sexual role in the home.” Consciously catering to the “female hunger for sexual phantasy,” Friedan opined, Peyton Place was another sad symptom of the feminine mystique.12

In the minds of both progressives and conservatives, in other words, fantasy and imagination could have only negative effects. In the minds of the former, they stirred up erotic and romantic emotions that supplanted reason, promoted female passivity, and undercut a woman’s autonomy and emancipation, while to the latter group of thinkers they inspired “ambitious excess,” provoking not only “disgust for all serious employments” but also a general dissatisfaction with one’s station in life.13 Only in recent years have attitudes toward the female reader begun to shift. Indeed, entire forests have surrendered themselves to the scholarly exploration of female acts of reading and the everyday uses of books. Second- and third-wave feminists have been especially astute in rethinking the effects of fantasy, repositioning the female reader as a complex social actor who is neither the passive receptor of textual messages nor extraneous to movements of social change.

Light fiction, it turns out, is serious business. For women and girls, who stood in the imaginative center of modern consumer society—men produced, women shopped—dime novels and newspaper stories called new attention to their spending habits. Hardly reflective of reality, the gendered narratives of consumption nevertheless gave women and their interests an unexpected edge by placing both at the center of modern consumer culture and rising concerns over its unpredictable emotional and psychic effects. Sharp dichotomies took hold: Was modern consumerist society and the “mass culture” it unleashed a new opiate or a potential site of rebellion and transformation? Labor historians have most often sided with Pastor, assuming, as her Enlightenment predecessors argued, that political engagement and collective action presupposed a coherent and fully formed political identity as “worker,” “woman,” “American.”

Ladies of labor and girls of adventure, however, tell a different tale. In her powerful study of labor politics in the early twentieth century, Enstad shows that dime novels, like clothes and movies, offered girls and women who labored in constrained circumstances a way to negotiate contradictory positions. Building on the work of Wendy Brown, Judith Butler, and Joan Scott, Enstad underscores the mutability of subjectivity, arguing that women’s political consciousness and actions emerged less from “clear and coherent identities” than from the contradictions laboring women experienced as terms lik...