![]()

1

COLLECTIVE MEMORY OF VIETNAM ANTIWAR SENTIMENT AND PROTEST

We [Harvard undergraduates] certainly could have seen that by keeping ourselves away from both frying pan and fire, we were prolonging the war and consigning the Chelsea boys to danger and death…. You could not live through those years without knowing what was going on with the draft, and you could not retain your sanity with that knowledge unless you believed, at some dark layer of the moral substructure, that [by getting out of serving] we were somehow getting what we deserved…. “There are certain people who can do more good in a lifetime in politics or academics or medicine than by getting killed in a trench”; in one form or another, it was that belief that kept us all going.

—James Fallows, “What Did You Do in the Class War, Daddy?” Washington Monthly, 1975

The best selling book, Lies my Teacher Told Me, explores the deplorable state of history curricula in secondary education, detailing “everything your American History textbook got wrong.” The bulk of its chapters are devoted to how particular episodes, people and themes of American history, such as “discovery,” Native Americans, racism, and “progress,” are discussed in a selection of history textbooks. Throughout, author James Loewen offers multiple interpretations as to why some facts are valued over others, why some distortions are rampant, and why certain stories are absent and others universal. He devotes his concluding chapters to answering, in more general terms, the questions that are implicit throughout: “Why Is History Taught like This?” and “What Is the Result of Teaching History like This?”1

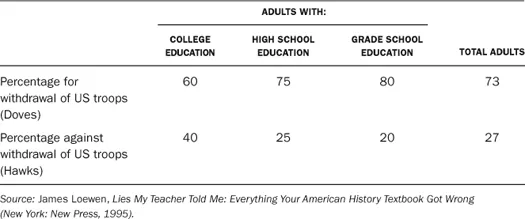

Loewen addresses the title question of this last chapter by choosing as emblematic a “Vietnam exercise” he conducted with “more than one thousand undergraduates and several hundred non-students” over the course of a decade.2 In these experiments, he gave his class or audience a chart that showed the public’s overall response to a Gallup poll question of January 1971: “A proposal has been made in Congress to require the US government to bring home all US troops before the end of this year. Would you like to have your congressman vote for or against this proposal?” After he had excluded the “I don’t knows,” 73 percent of respondents answered “yes” for withdrawal, whereas 27 percent answered “no.” Loewen left three columns of the chart preceding this overall breakdown blank, except for the headings of adults with “grade-school education,” “high-school education,” and “college education.” He asked students to fill in how they imagined these opposing attitudes about the war broke down according to education, which, as discussion had made clear, could also be understood as a proxy for class. By a margin that approached 10 to 1, students consistently indicated that the college-educated adults would have been most critical of the war; the nonstudents agreed at the only slightly less-overwhelming margin of 9 to 1. A “typical response” allocated the preponderance of withdrawal sentiment to the college-educated (90 to 10), close to average likeliness of calling for withdrawal (75 to 25) to the high school–educated, and least likely to call for withdrawal to the grade school graduates (60 to 40). Students explained their interpretations in varied but related ways: the better-educated someone was, the more critical and liberal they were likely to be; working-class people in the United States had a self-interest in being pro-war because their jobs were more likely related to war-making (in factories or the military); and other responses indicating that the “archetype of the blindly patriotic hardhat” was alive and well. Antiwar sentiment, the great majority of these college students and nonstudents agreed, was the province of the privileged; the lower down that ladder you were, the more likely you were to have supported the Vietnam War.3

But, as Loewen showed these students after they had made their speculations, the education/class breakdown of the “withdrawal” respondents was the opposite of what they had hypothesized. Answering his own question, he argues that the result of teaching history the way it is taught is that we get history wrong—we misapprehend and distort our past. The actual polls are shown in table 1.

The poll results were surprising to the respondents in Loewen’s experiment. He notes that they “surprise even some social scientists,” who should, he implies, know better. But should they? On a smaller scale than Loewen, I have encountered similar surprise as I described my project to others, who often asked me to explain, again: How did the sentiment against the war break down? Because wasn’t it the college students who marched against the war? Wasn’t it the elite and well-educated—intellectuals, peace activists, creative artists, and eventually prominent political leaders—who led the antiwar movement? Didn’t workers support the war? Weren’t the labor unions especially vocal in supporting the war? Didn’t workers beat up activists, proudly display American flags, and confront the students with forceful advice to “love it or leave it”?

Table 1 Antiwar sentiment, 1971

These suppositions have only gained greater ground in the wake of the current wars being fought by the United States. A Law and Order episode titled “Veteran’s Day” neatly captures the contemporary remembrance. In it, a Gulf War veteran who is grieving his son’s recent death in Afghanistan kills a young antiwar activist. Brian Tighe, the activist, is from a wealthy family, is “good at pushing other people’s buttons,” and comes off as a real jerk: blindly moralistic, self-righteous, out of touch with the real world that most ordinary people live in. We are told that Brian combatively argued against a community board proposal to rename a street after the veteran’s son, saying that streets should not be named after “murderers.” His girlfriend, Rehana Khemlani (who, although an American, is by name and appearance seemingly of Middle Eastern descent), defends Brian’s outrageous tactics, saying, “sometimes you just have to make a lot of noise to get people to listen.” Brian’s privileged WASP-y family, depicted as emotionally distant, nevertheless firmly defends his activism.4

Meanwhile, the accused and bereft Gulf War veteran is a letter carrier for the US Postal Service. His friends, other veterans, are similar working-class figures who collectively question Brian’s patriotism and priorities. “Guys like Brian Tighe make me sick—driving around with picket signs in his Daddy’s SUV, calling us murderers,” explains one friend of the accused. Matt, his son, “could have been the first person in [his] family to have gone to college,” but chose to be a “soldier like his father” instead. The father explains, “I love my country, and I raised my son to love it, too.”

Although the possibility is raised that Brian the activist “was against the war, not soldiers,” the city’s prosecutor himself asks, “Is it the truth—or is it just what we learned to say after Vietnam?” Brian’s antiwar activism is used against him in the trial, which turns on whether his behavior caused the veteran father “extreme emotional disturbance,” thereby mitigating the charge of murder. The jury is deadlocked, and a mistrial is declared. Commenting on the clear identification of the jury with the accused, the prosecutor notes there were “too many blue-collar people on the jury,” further observing that “the same people that get out of jury duty get out of serving in the army.”

Like the responses of Loewen’s students, this Law and Order story line is based on a dominant cultural narrative that makes sense of the relationships between antiwar activism and class and, relatedly, between the activists themselves and “regular people,” especially soldiers. And although Law and Order addresses contemporary issues—“ripped from the headlines” is its motto and modus operandi—Vietnam was the clear subtext, serving as a touchstone for the narrative. The figure of the veteran on trial here evokes the hardhats of 1970, whose violent rampages in lower Manhattan became the focus of the anxious response of the nation to the war and protests against it. The fantasy trial in this episode of Law and Order parallels a common response to the hardhat demonstrations of 1970, in which the violent aggressors become the righteously aggrieved victims. Prominent ideologues argued throughout and since the Vietnam War that the protesters “stabbed us in the back,” sapping the government and military of the will to keep fighting, and turning the public against the soldiers when they came home. This campaign to discredit the movement, placing the US defeat and the problems of veterans on its shoulders, found its grounds in charges of elitism. Those kinds of people—who are cowards, who do not send their sons to die, who avoid the basic duties of citizenship, who live in ivory towers—do not deal with the muck that the rest of us are in. Even more sympathetic observers such as Larry Heinemann, working-class Vietnam veteran and author of Paco’s Story, express this; Heinemann explains, “I know there were many people who opposed the war for moral and political reasons, but I also know there were many people against it because they were chicken and because their mommy and daddy had money to keep them in the streets.”5

The story line shared by these events, real and unreal, contains several common elements. Protesters are culturally and economically elite, as well as unsympathetic, bombastic, and insensitive. In contrast, working-class people are less educated but know the world better, are reflexively patriotic, and support the country when we are at war. Soldiers are the working-class victims of both the wars they fight and a culture at home that does not respect them economically or personally. Privileged youth do not carry their weight as citizens, and so regular citizens view these activists with skepticism and hostility, seeing their anger as incongruous to their advantages.

The cultural chasm between these groups is depicted as unbridgeable. In yet another description of Vietnam protest from a more current vantage point, John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge, Economist contributors, provide a vision of the period that is similarly rife with stereotypes:

Another divisive force was the antiwar movement. For many activists, the Vietnam War was the greatest evil of the day—and the counterculture was a natural accompaniment to a life of protest. For many rank-and-file Democrats, however, the antiwar movement was an abomination. What did the average workingman have in common with hippies who spent their time taking drugs and squandering their families’ trust funds? Or with students who desecrated the American flag? The antiwar protesters, most of whom would be given student deferments rather than being sent to fight, were even more unpopular than the war itself. Far too many of them seemed not just hostile to this or that American policy, but to America in general. The shooting of four students at Kent State in May 1970 may have inspired Neil Young to song, but a week later blue-collar America cheered when a group of hard-hat union construction workers in New York beat up a group of antiwar demonstrators.6

Blue-collar America, in fact, disapproved of the hardhat attacks, and other authors argue that it was precisely the over-the-top actions of the construction workers that catalyzed greater antiwar involvement from the official labor movement. Yet these facts do not interfere with the ruling narrative on the subject.7

Together these examples provide a basic outline of the conventional thinking that pervades US popular culture regarding the class dynamics of antiwar sentiment and protest during the Vietnam period and afterward. This common wisdom is typically shared, if more implicitly, among academic treatments as well. Many authors have written about the war in Vietnam and the struggles at home. Again and again, among the wars we fought during the Vietnam period, “the class war” figures with varying degrees of prominence.8

This historical memory of the class dynamics of the domestic response to the Vietnam War misapprehends the complexity of the class make-up, culture, sentiment, and action of the antiwar forces in the United States. It is this distorted memory, embodied in the students polled by Loewen and “Veterans Day” episode of Law and Order that I elaborate on in this chapter. Looking at film and television, history textbooks, academic studies, and mainstream political discourse, I trace the collective memory of the class dynamics of the period that remains with us today.

Collective Memory

Collective memory is a concept used to explain the social nature of our capacity for remembrances at both the individual and group levels. Sociologist Maurice Halbwachs provides the classic formulation of the relationship between this individual ability to bring the past to mind and the social interactions and group-belonging from which it springs. It is only in our interactions with others, he argues, that we successfully reconstruct the past—we rely on “social frameworks for memory”; “it is to the degree that our individual thought places itself in these frameworks and participates in this memory that it is capable of the act of recollection.”9 Our interactions with and affirmations from the group not only substantiate the memories we hold but, he argues, make possible their recollection. Beyond the commemorations and rituals that Halbwachs inv...