- 552 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

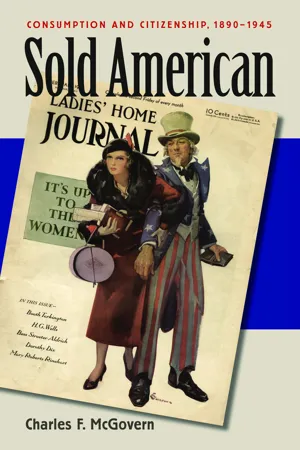

At the turn of the twentieth century, an emerging consumer culture in the United States promoted constant spending to meet material needs and develop social identity and self-cultivation. In Sold American, Charles F. McGovern examines the key players active in shaping this cultural evolution: advertisers and consumer advocates. McGovern argues that even though these two professional groups invented radically different models for proper spending, both groups propagated mass consumption as a specifically American social practice and an important element of nationality and citizenship.

Advertisers, McGovern shows, used nationalist ideals, icons, and political language to define consumption as the foundation of the pursuit of happiness. Consumer advocates, on the other hand, viewed the market with a republican-inspired skepticism and fought commercial incursions on consumer independence. The result, says McGovern, was a redefinition of the citizen as consumer. The articulation of an “American Way of Life” in the Depression and World War II ratified consumer abundance as the basis of a distinct American culture and history.

Advertisers, McGovern shows, used nationalist ideals, icons, and political language to define consumption as the foundation of the pursuit of happiness. Consumer advocates, on the other hand, viewed the market with a republican-inspired skepticism and fought commercial incursions on consumer independence. The result, says McGovern, was a redefinition of the citizen as consumer. The articulation of an “American Way of Life” in the Depression and World War II ratified consumer abundance as the basis of a distinct American culture and history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sold American by Charles F. McGovern in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Consumer Behaviour. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I: ADVERTISERS

CHAPTER 1: ADVERTISERS AND CONSUMERS, 1890–1930

Modern advertising is part and parcel of the whole set of thought movements and mechanical techniques which changed the medieval into the modern world.1

What a nation eats and wears—its pleasures, comforts and home conditions—these questions are being settled by the modern economic force called Advertising.2

Mr. James Ultimate Consumer is the most famous man in the world. He has to wear all the Knox hats, eat all the Premium bacon, listen to all the Victrolas and Panatropes, wear all the Fashion Park clothes, monkey with all the Radiolas, wind all the New Haven Clocks, roll over sleepy-eyed to shut off all the Big Bens in the morning, plod his way to work in all the Regals, poke his fingers through all the Adler gloves, step on all the Texaco, wear out all the Goodrich Cords, eat up all the Bean Hole beans, cram down his hungry neck all the Fifty-Seven varieties, find some reason for drinking all the Canada Dry, and take care of all the Camels in the world. James Ultimate Consumer—he’s the Man! He is “It” in every sense of the word. He is the destination of all made things.3

Advertisers should never forget that they are addressing stupid people—one of which I am whom.4

The American advertising business evolved to sell goods. From shadowy origins on the fringes of respectable bourgeois society before the Civil War, advertising became an important element of American culture in the half century after 1880. In those years advertisers defined themselves as a unique, influential profession to serve the industrial capitalism then revolutionizing daily life.5 Seemingly ubiquitous, advertising dominated both the structure and content of mass communications, assuming an unmistakable prominence in the built environment. Just as important, advertisers claimed for themselves the critical task of defining identity for Americans. Advertisements encouraged people to purchase a plethora of products to meet the material needs of their everyday lives. In conveying information about goods and ideal living, advertisers also provided images and prescriptions for the self.6 They encouraged consumers to understand themselves through their possessions and to fabricate their identities in and through things. In that process, advertising became “the privileged discourse for the circulation of messages and social cues about the interplay between persons and objects.”7 The late nineteenth-century experience of modernity in its many guises showed that the individual was not a fixed and stable character but a complex, changing entity shaped by the external world. Advertising encouraged customers—now increasingly termed “consumers” by the national corporations that were supplanting the face-to-face relationships of local commerce—literally to make themselves from their things.8 In this capacity, advertising shaped modern culture. This was achieved haltingly over many years and seldom with conscious purpose: after all, advertisers sold goods, not symbols. Yet they trafficked in images and ideals, and they educated consumers to interpret goods totemically as intimate, even animate, parts of their lives. As consumption helped define the self, advertisers taught Americans to view themselves as consumers.

Over its long history, critics have castigated advertising for encouraging demeaning behavior and crass concerns. They have charged that advertising fosters greed and insecurity and diverts us from humane values. Detractors assert that advertising’s depictions of social life insult our intelligence and strain our credulity. Such criticisms were leveled in 1904 as well as 2004. Yet however distorted their depictions of American life, advertising campaigns, I argue, served as social and political representations. Advertisers crafted and purveyed a vision of social life in the United States that highlighted consumption as the key not only to individual happiness but also to the health of American society. National media advertising presented a social order in which the consumer held a central place as both free individual and ideal citizen. Depicting the good life, the distribution of wealth, and a class system enforced though goods, advertisements worked as political documents. They intervened in broad economic and political discussions along with other forms of popular culture: the movies, periodical fiction, popular songs, the comics, theater. In company with editorialists, critics, and statesmen, advertisers interrogated politics and economics. The social world as seen in advertisements no doubt struck many as false and irrelevant, and we should on no account mistake them as transparent or reliable renderings of social experience. Yet advertising proved no more distorted than representations made by party politicians, self-help writers, or businessmen. As the voice of corporate capital, advertisers’ visions of wealth and the social order likely enjoyed an equal or greater popular appeal than others offered in entertainment, the press, or the pulpit. Throughout this study, the passionate critiques and defenses of mass-produced goods and culture reveal Americans’ investment in consumption’s manifold possibilities.9 By 1930, advertising was ingrained in American everyday life, not only as a thoroughly integrated tool of industrial capitalism, but also as a widely accepted cultural influence. By 1930, for better or worse, the United States was a consumer society. In order for that to have happened, advertisers first had to establish their authority with both business and the public.

SERVANTS AND SALESMEN: ADVERTISING PROFESSIONALISM AND IDEOLOGY

Early in 1909, the legendary Claude C. Hopkins, copy chief of Chicago advertising agency Lord & Thomas, addressed the Sphinx Club, a New York organization of advertisers, agents, and publishers:

From our desks we sway millions. We change the currents of trade. We populate new empires, build up new industries and create customs and fashions. We dictate the food that the baby shall eat, the clothes the mother shall wear, the way in which the home shall be furnished. We are clothed with no authority. Our very names are unknown. But there is scarcely a home, in city or hamlet, where some human being is not doing what we demand. The good advertising man comes pretty close to being an absolute czar.10

Hopkins’s self-satisfied oration sums up the contemporary claims of his profession. Between 1880 and 1930 advertising agents became indispensable to marketing goods. When Hopkins spoke, advertisers already worked for hundreds of businesses and influenced millions of purchasing decisions.11

Advertising men gained their influence because they developed specific expertise: publicizing information about goods to prospective buyers and conveying detailed information about retail customers to those with goods to sell. They became professionals, cultivating their expertise and selling it as a specialized, exclusive commodity. Veteran agent C. E. Raymond said bluntly, “The ‘goods’ an agency produces is service.” Advertising agents developed a professional ethos, based on their skills and alleged independence in judgment.12 Like other professionals, advertisers organized to promote their expertise and to serve as gatekeepers to professional practice. In addition, they mounted sporadic reform efforts and self-regulation of standards and practices.13 Ideals of service to both business and consumers undergirded the profession’s legitimacy and hastened its ascendance as a commercial and cultural institution.14 To understand fully advertising’s role in inventing the modern consumer requires an exploration of the service commodity advertisers sold to business and the consuming public.

The advertising business underwent a significant transformation after 1880. Challenged by industry’s needs to expand and rationalize markets, advertising agents changed their methods and redefined their functions. They had originally been speculative brokers in advertising space (newspapers, magazines, signage), but they now turned to preparing and placing advertising artwork and copy in that space for business clients.15 Ultimately, advertising agents helped invent marketing by identifying and analyzing appropriate segments of the populace who could buy their clients’ wares.16 Advertisers critically enabled the rise to national dominance of branded goods, which were mass-produced and sold under copyrighted and trademarked names. As historian Susan Strasser has shown, the branded goods system assumed its characteristic form by 1920, after a fierce thirty-year struggle over patterns and control of retail distribution. By pinpointing and fostering demand in the retail market for specific brands, advertising tipped the balance of power away from wholesale distributors and retail merchants, who had previously controlled the flow of goods to store shelves and influenced consumers’ selections. As Daniel Pope has observed, an advertiser “had to persuade consumers to buy his brand at the same time he convinced dealers that they could profit by stocking it.” Manufacturers increasingly used advertising to bypass wholesalers and retailers alike, ultimately winning the struggle to determine which goods made it to the shelves, the market basket, and ultimately the home.17 In this process advertising emerged as a beneficiary of as well as principal agent in the new distribution.18

Advertising’s primary service to business, then, was creating, maintaining, and increasing demand for goods. To foster demand, advertisers developed expertise in locating, addressing, and ultimately persuading consumers. By 1920, a number of agencies had become involved in their clients’ overall business operations. Led by the nation’s largest agency, J. Walter Thompson, advertisers routinely researched competitors and distribution conditions. Less frequently, they conducted investigations into markets, gathering information ranging from demographic data to taste preferences.19 They implemented a range of ancillary services for clients, such as devising brand names (such long-lived brands as Uneeda Biscuit, Karo Syrup, Yuban Coffee, and Kelvinator were all coined by advertising agents), preempting competitors’ entry into markets, designing packaging, and originating what eventually became corporate public relations.20 Yet advertisers always accompanied this vision of business acumen by portraying themselves as public servants with information about commodities and values that would enhance the public welfare.21 Identifying their clients’ interests with the general good of the public and the state, advertisers adopted a stance of enlightened stewardship. They accomplished this largely by portraying products as offering solutions to otherwise baffling personal difficulties.22 Advertisements depicted products as the means to self-transformation, and ad men held themselves out as the dispensers of happiness and enlightenment. The material modernity offered in advertising placed America at the pinnacle of world civilizations.

Like many different elites, advertisers viewed themselves as guardians of greater values. They linked consumption to national progress, one of the most cherished core beliefs about American life.23 For advertisers, progress entailed the forward advance of higher civilization through goods; as agents of commerce, advertisers were fundamentally servants of civilization, the sum total of human achievement (fig. 1.1). “Yours is the profession of enlightenment,” one advocate wrote. “A promoter of commerce? Yes. An instrument of distribution? Assuredly. But you think too meanly of advertising if you confine it to these terms. It is an agency of civilization.”24 The trade journal Printers’ Ink claimed in 1889 that advertising “is a test of the increasing wants of the people . . . a sign of civilization.” According to advertising writer Edwin Balmer, “The rapidity of our progress as a nation is determined very largely by the efficiency and effectiveness of our advertising. . . . Individuals, communities and races are progressive as they acquire new needs—as they learn to make things and to use them.”25 Ad men interpreted the variety and numbers of goods they sold as the raw evidence of the quality of civilization itself. “Look for a nation whose people are not advertisers and you will find a country whose inhabitants are either semi-civilized or savages,” announced one advertising writer.26 “Give me a list of a nation’s wants and I can tell you of the state of that nation’s civilization,” claimed the president of the Alexander Hamilton Institute, a correspondence school. “If their wants are increasing in number and quality, we know that the nation is alive, that it is not decadent. The man whose wants are those of his forefathers [is] making no progress.” The extent of advertising thus reflected a nation’s progress.27 Perhaps the pinnacle of such advertising puffery and self-congratulation was reached in this pious sentiment: “The creator, in his infinite wisdom, could confer no greater benefaction upon an increasing population than that which we find in the one word ‘advertising.’ ”28

Spreading civilization meant deploying advertising throughout the world. Ad men contrasted the United States’s leadership in advertising and consumption to nascent commerce in other countries.29 Long before the Cold War’s contrasts of capitalism and communism made “underdeveloped” synonymous with “underconsuming,” China and Russia frequently served as Madison Avenue’s examples of nations whose ignorance of advertising and material desire kept them in semibarbarity.30 Implicit in these views was a corporate anthropology of mass consumption, no less articulate, if much more simplistic, than the complex taxonomies produced in the academy. A...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Sold American Consumption and Citizenship, 1890–1945

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction. Inventing Consumers: Citizenship and Culture

- Part I. Advertisers

- Part II. Consumerists

- Part III. Citizens and Culture

- Epilogue. Price Check

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index