eBook - ePub

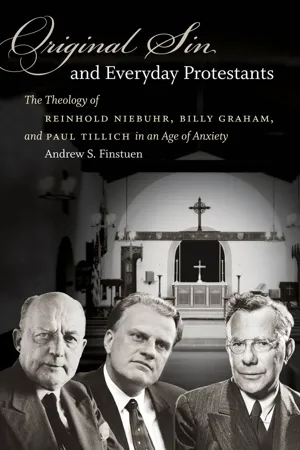

Original Sin and Everyday Protestants

The Theology of Reinhold Niebuhr, Billy Graham, and Paul Tillich in an Age of Anxiety

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Original Sin and Everyday Protestants

The Theology of Reinhold Niebuhr, Billy Graham, and Paul Tillich in an Age of Anxiety

About this book

In the years following World War II, American Protestantism experienced tremendous growth, but conventional wisdom holds that midcentury Protestants practiced an optimistic, progressive, complacent, and materialist faith. In Original Sin and Everyday Protestants, historian Andrew Finstuen argues against this prevailing view, showing that theological issues in general — and the ancient Christian doctrine of original sin in particular — became newly important to both the culture at large and to a generation of American Protestants during a postwar “age of anxiety” as the Cold War took root.

Finstuen focuses on three giants of Protestant thought — Billy Graham, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Paul Tillich — men who were among the era’s best known public figures. He argues that each thinker’s strong commitment to the doctrine of original sin was a powerful element of the broad public influence that they enjoyed. Drawing on extensive correspondence from everyday Protestants, the book captures the voices of the people in the pews, revealing that the ordinary, rank-and-file Protestants were indeed thinking about Christian doctrine and especially about “good” and “evil” in human nature. Finstuen concludes that the theological concerns of ordinary American Christians were generally more complicated and serious than is commonly assumed, correcting the view that postwar American culture was becoming more and more secular from the late 1940s through the 1950s.

Finstuen focuses on three giants of Protestant thought — Billy Graham, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Paul Tillich — men who were among the era’s best known public figures. He argues that each thinker’s strong commitment to the doctrine of original sin was a powerful element of the broad public influence that they enjoyed. Drawing on extensive correspondence from everyday Protestants, the book captures the voices of the people in the pews, revealing that the ordinary, rank-and-file Protestants were indeed thinking about Christian doctrine and especially about “good” and “evil” in human nature. Finstuen concludes that the theological concerns of ordinary American Christians were generally more complicated and serious than is commonly assumed, correcting the view that postwar American culture was becoming more and more secular from the late 1940s through the 1950s.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Original Sin and Everyday Protestants by Andrew S. Finstuen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Chapter 1: Protestantism in an Age of Anxiety

The Captive and Theological Revivals of Midcentury

From 1945 to 1965, Americans experienced a time of immense promise and equally immense peril, one that inspired W. H. Auden’s 1947 poem “The Age of Anxiety.” Social and cultural commentators quickly adopted Auden’s phrase to describe the postwar mood, making “anxiety” the buzzword of the era.1 Leonard Bernstein, for example, read Auden’s poem in the summer of 1947 and composed a symphony to capture the feelings of anxiety pulsing through the culture. At the heart of the composition, Bernstein wrote, was “the record of our difficult and problematic search for faith.”2

Contrary to the self-satisfied, placid image of the postwar era—especially the 1950s—Americans in these years, as Auden, Bernstein, and others noted, were an anxious people. The sources of their anxiety ranged from the possibility of World War III—including the prospect of nuclear holocaust—to the health of the postwar economy. These abstract worries mingled with the lingering emotional toll of World War II and the outbreak of actual war in Korea just five years after V-J day. Upheavals caused by mass migration to the suburbs, questions about equal citizenship for African Americans, and the timeless search for meaning amid the mystery of existence also occupied the attention of the citizenry. Consequently, halcyon portrayals of American life after the war neglect the palpable cultural uncertainty of the period. As Robert Wuthnow has argued, “The prevailing mood, then, was by no means one of untrammeled optimism. Some rays of hope had broken through at the conclusion of the war, but much of the sky remained dark.”3

Amid the anxiety, Americans flocked to Protestant churches, hoping that some light might penetrate the threatening darkness. The result was an astounding renewal within Protestantism, the twentieth-century equivalent of the First and Second Great Awakenings. Polls indicated that more than 90 percent—at times as many as 98 percent—of Americans professed belief in God in the late 1940s and 1950s. In 1954, the New York Times noted the recovery of church membership after the “religious depression” of the 1930s. From 1940 to 1954, Americans joined churches at three times the rate they had from 1928 to 1940. Protestant churches received the majority of the new members, pushing the Protestant share of American churchgoers to nearly 59 percent. The most solid evidence—literally—of this religious awakening was the abundance of new churches popping up across the country. Newsweek called the construction boom “the most extensive church-building job in history.” Protestantism had, it appeared, rebounded from its depression.4

Within this rising sea of Protestant belief, however, two revivals set its tidal patterns. In 1959, theologian John Bennett described these dominant trends within Protestantism in an editorial simply but aptly titled, “Two Revivals.” Bennett, a friend and colleague of both Niebuhr and Tillich, looked back over the 1940s and 1950s and identified both the “revival of interest in religious activity” and the “theological” revival as primary influences within postwar Protestantism. He defined the first broadly: a movement typified by a “vague religiosity” that sanctioned American cultural values and stressed “a gospel of love without the Cross, of ‘acceptance’ without judgment.” The other revival, Bennett noted, drew from theologians like Karl Barth, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and Emil Brunner in Europe, and from Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich in America. The effect of their collective theological endeavors was to recover “the profound Christian diagnosis of the human situation and the gospel of God’s forgiveness.” Ultimately, he distinguished the two revivals by assessing their respective relationships to American culture: “The one [theological] has encouraged the independence of Christian faith from culture; the other [religious activity] has encouraged the assimilation of the faith to culture.” As Bennett saw it, while the theological revival was less widespread than the religious activity revival, it nevertheless kept pace with its competitor.5

This analysis employs Bennett’s categories for the two dimensions of the revival, though with some revision. While Graham was no theologian, he joined Niebuhr and Tillich in their advocacy of the “independence of Christian faith from culture.” When discussing the “assimilation of faith to culture,” the term “captive”—used at the time to describe this process—will serve as a shorthand designation for Bennett’s rather awkward phrase, “revival of religious activity.” Norman Vincent Peale, author of The Power of Positive Thinking (1952), figures prominently in the analysis of “captive” expressions of Protestantism.

Placing Billy Graham on the side of the theological revival challenges conventional readings of his ministry. Graham is often erroneously seen as Peale’s ally in the captive revival. To be sure, Graham at times preached a Gospel captive to the culture, but his ministry did not end there, as Peale’s did. In fact, as a consequence of his evangelical theology of sin, Graham could and did offer trenchant criticism of American culture. Thus, although theologically pedestrian in comparison with Niebuhr and Tillich, Graham nevertheless advanced a definite theology of human nature, one that drew from such church fathers as Augustine and from his own interpretation of Scripture.

Though the theological revival was without doubt the principal bearer of the original sin moment, its full character is thrown into sharper relief by contrasting it to the captive revival. After all, both revivals emerged out of the same ambivalent postwar mood, the same Age of Anxiety. Their responses to the paradoxical and harrowing context of the era were predictably quite distinct. Protestants within the captive revival, most notably Peale, offered a triumphal message in the face of the anxiety and ambiguity of the period. It was as if they took their theological cues from the popular 1945 song “Accentuate the Positive,” literally encouraging believers to “Eliminate the negative; Latch on the affirmative; Don’t mess around with Mr. In-between.”6 By contrast, Protestants within the theological revival, with Niebuhr, Graham, and Tillich at the helm, placed the promise and peril of American life in the context of sin. For them, the anxiety within the culture was a function of sin writ large, but it was also a reflection and consequence of individual sin.

Bennett’s two revivals had roots in the paradoxical American cultural climate that followed World War II. For a quarter century after the war, although America had risen to political and economic preeminence, its citizenry was steeped in the tragic dimensions of the new character of American life. Many Americans were touched by promise, to be sure, but the perilous international and domestic context in which they lived was an ever-present corrective to any unbridled optimism about the future.

Tensions abroad quickly terminated the prospect of a longstanding peace after the war. The jubilation of V-E and V-J days was short-lived as Americans witnessed the world move from a hot war to a cold war. Truman’s pledge in 1947 to intervene in Greece and Turkey to counter communist advances raised the possibility of another global conflict. Thereafter, the Czechoslovakian coup (1948), the Soviet detonation of an atomic bomb (1949), the “loss” of China to communism (1949), and the outbreak of the Korean War (1950) heightened concerns about American national security. The Soviet possession of a nuclear weapon was of course the most dramatic threat to American peace of mind. The specter of an atomic mushroom cloud haunted the sunny forecast of post–World War II American prosperity.7 Taken together, these events induced nightmares in the midst of the popularly imagined heyday of the American dream.

The domestic situation, while not as strained as the fragile stability of the international community, nevertheless contributed to the anxieties of postwar Americans. In the first place, the idea of “postwar America” was a misnomer. The war lived on as Americans processed the brutality of World War II and the soldiers themselves reckoned with their homecoming and reintegration into society. The violence of the war affected millions of Americans who mourned the loss of more than four hundred thousand fathers, brothers, sons, and friends to the battlefields of Europe and East Asia. The horrors of the Holocaust and of Hiroshima and Nagasaki confronted still more millions with the magnitude of humanity’s capacity for inhumanity. In the latter case, John Hersey’s bestseller, Hiroshima (1946), challenged Americans to contemplate the full significance of the decision to annihilate that city with a single bomb. In that same year, William Wyler’s film The Best Years of Our Lives also attended to the complexities of war with his illuminating depiction of the GIS’ return to American soil. The film won best picture honors in 1946 for its portrayal of battle-scarred veterans—one of the main characters of the film was played by an actual veteran who lost his arms overseas—facing the difficulties of relationships, work, and happiness in civilian life.8

The experiences of the troubled protagonists of Wyler’s film mirrored those of many former soldiers after the war. In particular, many veterans exhibited less certainty and patriotic fervor about the war than retrospective celebrations of their sacrifices have allowed. For instance, Time magazine reported the results of one army poll taken in early 1946, which found, “A lot of G.I.s are wondering why they ever had to fight the war.”9

Other veterans were simply and understandably traumatized. Even Sloan Wilson’s quintessential suburban novel, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, captured the mental consequences of the war. The novel’s main character, Tom Rath, is haunted, not unlike Wyler’s characters, by the bloodletting of World War II. Flashbacks of his war experiences intrude on Rath’s suburban existence. Rath, after all, had accidentally killed his best friend, Frank Mahoney, with an errant hand grenade toss while fighting in the Pacific theater. Wilson recounts the memory of this horrible event in stark detail. Rath rushes to his friend’s aid only to find “Mahoney’s entire chest had been torn away, leaving the naked lungs and splintered ribs exposed.” Momentarily deranged, Rath fights on, carrying Mahoney’s corpse as he disposes of several “Japs.” When finally he releases his friend’s body for burial, he notices that several of his comrades at arms are collecting mementos, “making necklaces of teeth and fingernails.” Later he hears that others had boiled Japanese heads “to get the skulls for souvenirs.” Unfortunately, these ghoulish practices were not limited to the pages of fiction but were in fact a regular occurrence. In 1944, Life magazine published a picture of a young woman with a Japanese skull sent to her by her fiancé, and treated it as a human-interest story.10

Rath strives to forget such “incomprehensible” facts of his war experience as he faces life in 1953. He ruminates on the idea that just as the army begins with basic training, it ought to end with “basic forgetting.” Rath’s experience was not an isolated one. Several advice books and numerous articles in such popular periodicals as Collier’s, the Saturday Evening Post, and Life offered strategies for relating to America’s troubled veterans.11

The legacy of the war was but one powerful force that contributed to the dark shadow of midcentury America. Economic concerns troubled Americans as well. The health of the postwar economy was by no means certain. Rising inflation stirred rumors about the possible return of the Depression, while recession threatened in 1954 and became a reality in 1958. As the war overseas concluded, a labor war stateside began. During late 1945 and early 1946, strikes in the auto and coal industries slowed the nation’s economy, while the railroad unions sparked “pandemonium” by threatening full stoppage of service. The various walkouts in these years amounted to the largest labor protest in American history (5 million workers in all) and left doubts about the endurance of wartime unity.12

Despite the nation’s recession and its labor problems, the war had jumpstarted the economy. Many Americans were flush with wartime savings and ready to treat themselves to more comfortable living after four years of rationing. Yet it seemed that the newfound prosperity created as much anxiety as it alleviated. Postwar wealth, according to an article in Time, brought “millions of new homes dotting the countryside, and the tangle of TV antennas atop them; the ribbons of superhighways and the relentless stream of flashy new autos flowing down them.” But, Time concluded, “wealth has also brought problems.” Overproduction, rampant consumerism, and an accelerated pace of life contributed to feelings of dissatisfaction in spite of the material abundance. In addition, the article noted the postwar increases in poverty and crime, foreshadowing Michael Harrington’s dismal appraisal of the fortunes of Americans in The Other America (1962).13

The economic vertigo was, however, only part of the problem. The suburban migration—the second “Great Migration” of the twentieth century—exacerbated these socioeconomic tensions. Eighteen million people moved to the suburbs between 1950 and 1960. By their design, the suburbs greatly reduced the opportunity for social interaction and support within the neighborhood. This massive exodus replaced neighborhoods centered on the corner market and city park with atomized housing developments. The isolation of the suburbs was enhanced by the mobile and transitory nature of the communities, as 25 percent of the population in America moved at least once a year in the midcentury era. The automobile was now king: garages reduced curbside conversations, and residents drove to anonymous shopping centers to purchase goods and services. While suburbanites carved out their slice of the American dream, they hardly could have expected that this radically altered lifestyle would augment feelings of anxiety and alienation.14

Suburban malaise was especially acute among women. Women endured an oppressive domestic ideal and, as they joined the labor force at unprecedented rates, worked in uninspired clerical jobs. Women, then, worked a double shift, putting in their nine-to-five only to return home to cook, clean, and care for children. The situation left many women frustrated and bored. For some, alcohol, drugs, and social clubs filled the void. Researchers compiled startling statistics charting the surge in consumption of alcohol and tranquilizers. One suburban woman, as recorded by historian Stephanie Coontz, summarized her experience of the times with a description of “the four b’s . . . booze, bowling, bridge and boredom.”15

While suburban anxiety was certainly a concern, leading postwar intellectuals worried more about American conformity. David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd (1950) chronicled the transformation of American character from “inner-direction” to “other-direction.” Perhaps more than any oth...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Original Sin and Everyday Protestants The Theology of Reinhold Niebuhr, Billy Graham, and paul tillich in an Age of Anxiety

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One

- Part Two

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index