- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Michael Ballard provides a concise yet thorough study of the 1863 battle that cut off a crucial river port and rail depot for the South and split the Confederate nation, providing a turning point in the Civil War. The Union victory at Vicksburg was hailed with as much celebration in the North as the Gettysburg victory and Ballard makes a convincing case that it was equally important to the ultimate resolution of the conflict.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Vicksburg by Michael B. Ballard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Town, a River, & War

While the United States was still a young republic, pioneers moving west noticed attractive land sitting on high bluffs above a sharp hairpin turn in the Mississippi River. An ideal place for a town, some observers said, and a South Carolinian named Elihu Hall Bay thought so too. By 1800, Bay had title to some 3,000 acres of this high ground that had come to be known as the Walnut Hills. The name no doubt evolved from boatmen who came to recognize the “halo of walnut trees high above the river” as a landmark. A future observer of the area would cynically describe it: “After all the big mountains and regular ranges of hills had been made by the Lord of Creation, there was left on hand a large lot of scraps, and these were dumped down at Vicksburg into a sort of waste heap.” A kinsman of Bay’s named Robert Turnbull later inherited the property and was more interested in planting cotton than a community. These Mississippi Territory hills along the river seemed to take on a life of their own, however, and houses began to appear around the edges of Turnbull’s real estate.1

Another cotton planter named Newitt Vick, a visionary neighbor of Turnbull’s, recognized settlement possibilities and began marking off lots to sell in 1819. A native Virginian, Vick was a circuit-riding Methodist preacher who had brought his family into Warren County, named for Revolutionary War hero Joseph Warren, in 1809, eight years before Mississippi entered the Union as the twentieth state. Vick died of yellow fever before the town that would bear his name, Vicksburg, was officially incorporated in 1825, but his descendants made sure it happened.2

Indian land cessions in Mississippi in the early days of statehood increased cotton planting in the state, thereby increasing the need for a river port on the Mississippi where the white gold could be transported to New Orleans and beyond. The village on the bluffs proved an ideal spot for such a port, so Vicksburg grew rapidly, soon ranking second

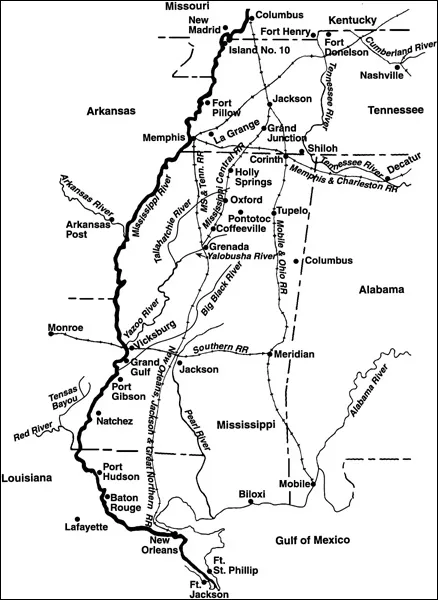

The General Area of the Vicksburg Campaign. Map by Becky Smith.

only to Natchez, its river neighbor to the south, as a center of economic activity. The peculiarities of the river made the city’s prominence possible. After the Mississippi passed by the mouth of the Yazoo, it started turning north and “suddenly began to change in temperament; the current began to move rapidly,” and just above Vicksburg it looped. Then the “channel made a complete 180-degree turn around the tip of De Soto Point and flowed in a torrent right down the city waterfront.” The current was fast and tricky, but due to the “deep water off the bank, regardless of water stage,” the long waterfront made a good docking area, and a reliable one, since the water could not eat away at the “solid limestone and shale” at the core of the bluffs. More and more people moved in; goods and services increased; and soon Vicksburg became the county seat of Warren County, taking that honor from the village of Warrenton a few miles downriver.3

Because Vicksburg was on a mighty river that led to the outside world, its growth followed different patterns than the county in which it sat. The society that dominated the town was “heterogeneous and fluid,” “more dynamic, more complex” than the rural adjacent areas. Like a mini-city, Vicksburg developed into well-defined neighborhoods during its formative years. The business district dominated the landscape on the east bank of the river up to the courthouse bluff. Residential areas then took over and through the years spread among the hills. To the north lay the “Kangaroo,” a crude, backstreet area haunted by riffraff, including shady gamblers, prostitutes, and drunken brawlers. When the Kangaroo burned to the ground in the early 1830s, few beyond its occupants mourned its loss.4

Despite the welcome growth and accompanying thriving economy, Vicksburg citizens deceived themselves into thinking that they could control the social dynamics various people brought to the city. Worry over undesirables, loosely defined as any outsider, fueled the growth of local militia. Right up to the eve of the Civil War, many residents seemed to fear these outsiders more than the threats of slave revolts that haunted other antebellum white southerners. Underscoring societal tensions was a July 4, 1835, picnic at which a drunken gambler insulted finely dressed militia. The incident triggered violent confrontations between citizens and the clique of gamblers common in river towns. By the time things settled down, the original perpetrator had been tarred and feathered, several on both sides had been shot, and the gamblers who could not escape were hung en masse.5

Three years later, civic leaders turned their wrath on river men whose merchandise-laden flatboats competed with the city’s more legitimate businesses, owned by local businessmen. Taxes levied on the boatmen had little effect; most carried so much cash that they paid without wincing. So the taxes kept going up until resistance finally brought an armed standoff, which fortunately fizzled before anyone was harmed. A circuit judge later ruled in favor of the river men, but a message had been sent. The city would not stand idly by and be taken advantage of by interlopers.

In spite of the paranoia, Vicksburg continued to grow, surviving the national financial panic of 1837 and a destructive city fire in 1846. The latter year the town watched excitedly as the First Mississippi Regiment was organized locally, with prominent planter Jefferson Davis elected as its colonel. The town that did not want outside intervention had no compunction about sending its sons to intervene in the conflict between Texas and Mexico that resulted in the Mexican War. Their attitudes typified southern support for Texas, where slavery, the major factor that unified white southerners, had been introduced.6

The 1850s brought prosperity, and with it came an increasing number of fine homes for which Vicksburg, like Natchez, became famous. The population increased as well; by 1860 Vicksburg would have 4,500 residents, more than the capital city of Jackson, some forty miles to the east. Irish immigrants accounted in large measure for this growth; others came from England and Germany. The city that feared the newcomer had become cosmopolitan in spite of itself. The ethnic influx brought economic diversity to the river city, the federal census reporting some 193 different occupations in 1860.7

Despite its progress and its handsome residences, Vicksburg on the eve of civil war was in many respects an eyesore. Several wooden buildings stood unpainted; unfettered hogs roamed unpaved streets and, along with equally free-ranging, mostly homeless, dogs, ripped open anything that promised to be food. Roaches had become a citywide problem. Citizens did occasionally take action; one report in 1860 indicated that 129 homeless dogs had been rounded up and drowned in the river. A few streets were improved, and a magnificent county courthouse dominated the city’s skyline.

Yet problems persisted. Four-legged troublemakers and vermin could be more easily dealt with than drunks and prostitutes, undesirables that continued to persist despite the attempted 1830s purge. Like other residents of the slave South, Vicksburgians decided that rather than deal with the unpleasantness all around, they would strengthen community ties by organizing exclusive clubs and doing charity work. Many seemed to resolve their attitudes against “them” by simply pretending that the undesirables did not exist. Women especially busied themselves reaching out to the sick and unfortunate. Unfortunately for those engaged in self-deception, national issues insistently intruded into their private world.

In Vicksburg, whatever oratory local secessionists mustered in support of the growing movement in the South, fueled by the presidential election of 1860, was drowned out locally by majority Whig counterarguments. Merchants especially feared the business disruptions that were bound to come if Mississippi left the Union. Yet Vicksburg was not an island that could ultimately go its own way economically or socially. The town’s ongoing efforts to shield itself from national dynamics would continue to be illusory and futile.8

As November 1860 and the national presidential election approached, tensions increased nationwide and especially in Vicksburg. The national Democratic Party had split, and the Southern wing had chosen John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky as its presidential candidate. Jefferson Davis, a Warren County resident, United States senator, Mexican War hero, and former secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce, came home to campaign for Breckinridge. Ostensibly an opponent of secession, Davis had become more belligerent in tone of late, a reflection of white Southerners’ state of mind. Though Davis knew that with the Democrats split Breckinridge could not win, he had decided that Southern honor was more important than victory. He warned that his county and his state would be degraded by submission to Northern demands that slavery not be extended to U.S. territories and new states. These demands threatened the future of the institution of slavery. If Mississippi resisted those threats, Davis said, and the North should respond aggressively, the state would “welcome the invader to the harvest of death.”9

Davis’s position did little to change attitudes of conservative old-line Whigs. While some Vicksburgians listened to secession talk, many more attended a rally in support of the newly formed Constitutional Union Party, an antisecession group that nominated Tennessean John Bell as their candidate. Like Breckinridge, Bell had little chance of winning, especially since Northern Democrats had rallied behind Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. Many citizens of Vicksburg who abhorred the idea of separation from the Union felt, however, that they had little choice but to go with Bell. They valued compromise and peace more than the vague and risky concept of Southern honor that Davis embraced. They could not see “honor” in the potential loss of their livelihoods and even their lives on the altar of war.

When local ballots were counted, conservative economic interests prevailed, barely. Bell received 309 votes, Douglas 52; and Breckinridge ran a close second with 296. The Republican Party candidate, Abraham Lincoln of Illinois, was not on the ballot.10 Unionists could rightly claim victory, but hardly a resounding one; the election no doubt startled many Whigs who could see their long-time influence waning. Nationwide, the feared Republican Party, founded on free-soil, abolitionist principles, won the presidency. Lincoln opposed any further expansion of slavery, and rabid secessionists would seize the moment, making life ever more miserable for secession opponents in the South like those in Vicksburg.

Resistance in the hill city remained strong for a time. Many residents refused to budge on the question of separation until they no longer had a choice. They had a much more realistic view of what war would mean than did the fire-eating secessionists that increasingly dominated Mississippi. The town’s “ties with the North—especially the river connection with the Midwest—fear of war stemming from property and personal hazard, genuine love for the Union, and strong partisan, political feelings which made the conservatives distrust the demagogic, secession-inclined Democrats were the forces which worked to hold the city apart from most of the state.”11

A local paper, predictably named the Daily Whig, called for calm in the wake of Lincoln’s election. The editor wrote hopefully: “We call upon the people, . . . now that the issue is made, to choose under which banner they will serve—disunion, with all its attendant horrors of rapine, murder and Civil War or Union with the guarantees of the Constitution to protect us, and one-half of the people of the north to sympathise and aid us in maintaining our rights.”12

The paper almost daily tried to calm fears and promote faith in the righteousness of the Union. When Stephen Douglas stopped by, en route to his plantation in Washington County, Mississippi, north of Vicksburg, the editor reported on Douglas’s twenty-minute speech, in which he assured listeners that Lincoln, an old political foe of Douglas’s, would be powerless to interfere with Southern slavery. The Congress would control the president, Douglas said, and the Illinois senator went on to praise local support for the Union in this, the “most important point in Mississippi.”13

A few days later, attendees of a large pro-Union rally in town heard other speakers urge caution. They agreed that if Lincoln insisted on embracing abolitionism, then the South would have a right to leave the Union, but such action should be taken by all states at once. Clearly, they hoped such would not be the case, but if such action became necessary, they wanted it to be orderly and with unanimity, rather than have Mississippi act hastily on its own. Their words indicated, too, a realization that secession might soon be too powerful a movement to be checked.14

Resistance to secession continued. When the Mississippi state legislature called for elections to a state secession convention to be held on December 20, pro-Unionists in Vicksburg and Warren County went to work, and their candidates outpolled separatists by 561 to 173. The secessionist editor of a Vicksburg paper called the Daily Citizen cried fraud, but to no avail. Two Unionist delegates thus represented Warren County at the convention, which met on January 7, 1861. Despite their local victory, neither Warren delegates nor their supporters had any illusions that Mississippi could be held in the Union. Yet it was a bit of a surprise when one of the two broke ranks and voted with eighty-three other representatives for secession. The other delegate remained loyal to his cause, and was one of fifteen delegates who voted against secession. In addition to the old Whig counties along the river, the hill counties of northeastern Mississippi offered strong opposition; it was an area with a relatively small slave population that, like Vicksburg, would experience firsthand the harshness of war.15

Secession had come to Mississippi, and many, especially in the capital, Jackson, rejoiced amid cannon firing and bells ringing. Few such expressions could be found in Vicksburg. No sounds of gunfire or fireworks rang through the hills, but the absence of celebration did not necessarily indicate sulking. However mistaken the pro-Unionists believed their fellow citizens to be, most would not turn their backs on Mississippi. One antisecessionist wrote to the Whig: “It is enough for us to know that Mississippi, our State, our government has taken its position. We, too, take our position by its side. We stand ready to defend her rights and to share her fate.”16

Residents in the states of Illinois, Ohio, Wisconsin, Iowa, and other areas of the old Northwest Territory understood clearly the economic ramifications of a closed river. Yet their anger at that possibility reflected much more. Canals and railroads had developed to the point that farmers could get their goods to Eastern markets without the river, though many still used the Mississippi. For these people, the river had always been more than an economic lifeline. Through the years, it had become “a symbol that incorporated their prosperity, their regional pride, and their allegiance to the national union.” They wanted to keep the “status quo, express the power of their region, and maintain the economic benefits that had proved beneficial in the past.”

The United State...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Vicksburg

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 A Town, a River, & War

- 2 Summer Stalemate

- 3 Counterstrokes & Controversies

- 4 Race to Vicksburg

- 5 Bloody Bayou & the Wild Goose

- 6 Disputes, Diversions, Failures

- 7 Turning Point

- 8 Port Gibson

- 9 Raymond & Jackson

- 10 Champion Hill & the Big Black

- 11 Assaulting Vicksburg

- 12 Siege Operations

- 13 Surrender & Second Jackson

- 14 Aftermath & Legacies

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index