eBook - ePub

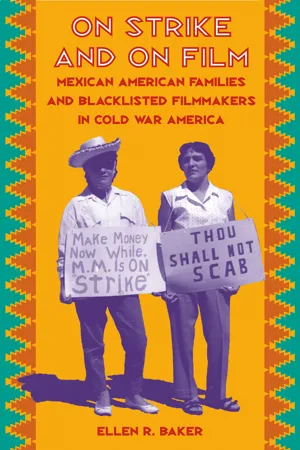

On Strike and on Film

Mexican American Families and Blacklisted Filmmakers in Cold War America

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

On Strike and on Film

Mexican American Families and Blacklisted Filmmakers in Cold War America

About this book

In 1950, Mexican American miners went on strike for fair working conditions in Hanover, New Mexico. When an injunction prohibited miners from picketing, their wives took over the picket lines — an unprecedented act that disrupted mining families but ultimately ensured the strikers' victory in 1952. In On Strike and on Film, Ellen Baker examines the building of a leftist union that linked class justice to ethnic equality. She shows how women’s participation in union activities paved the way for their taking over the picket lines and thereby forcing their husbands, and the union, to face troubling questions about gender equality.

Baker also explores the collaboration between mining families and blacklisted Hollywood filmmakers that resulted in the controversial 1954 film Salt of the Earth. She shows how this worker-artist alliance gave the mining families a unique chance to clarify the meanings of the strike in their own lives and allowed the filmmakers to create a progressive alternative to Hollywood productions. An inspiring story of working-class solidarity, Mexican American dignity, and women’s liberation, Salt of the Earth was itself blacklisted by powerful anticommunists, yet the movie has endured as a vital contribution to American cinema.

Baker also explores the collaboration between mining families and blacklisted Hollywood filmmakers that resulted in the controversial 1954 film Salt of the Earth. She shows how this worker-artist alliance gave the mining families a unique chance to clarify the meanings of the strike in their own lives and allowed the filmmakers to create a progressive alternative to Hollywood productions. An inspiring story of working-class solidarity, Mexican American dignity, and women’s liberation, Salt of the Earth was itself blacklisted by powerful anticommunists, yet the movie has endured as a vital contribution to American cinema.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access On Strike and on Film by Ellen R. Baker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Early on the morning of October 17, 1950, zinc miners finished the graveyard shift at the Empire Zinc Company in the village of Hanover, New Mexico. They climbed out of the mine shaft and into the sunlight illuminating the mountains in this southwestern corner of the state. Other workers gathered outside the company’s property—not to begin the day shift, however, but to begin a strike. Contract negotiations between their union, Local 890 of the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers (Mine-Mill), and Empire Zinc had finally broken down around midnight, with the company rejecting union demands for collar-to-collar pay, paid holidays, wages matching the district’s standards, and a reduction in the number of job classifications.1 This last demand was aimed at combating the dual-wage system in which Mexican American workers routinely earned less than Anglo workers, for a large number of classifications made it easier for employers to keep Mexican American miners in low-paying jobs. Striking to press their claims, 140 men picketed two entrances to the Empire Zinc property. Their picket lines completely shut down the mine.2

A year later, the picket lines were still in place, still blocking the mine entrances, and Empire Zinc was barely operating. But if the picket lines continued to perform the same function, they had nonetheless been completely transformed: the marching picketers were all women and children, not the men who walked out on that October morning in 1950. This dramatic change had taken place in June 1951. The strike began as a typical conflict between miners and their employer over work conditions and wages, but like many labor conflicts, especially in single-industry towns like Hanover, the strikers depended on a wider community, especially their wives, for support. And when the Empire Zinc Company got a court injunction prohibiting striking miners from picketing, miners’ wives took over the picket lines. This role reversal sparked conflict between husbands and wives. Although husbands knew that they could no longer picket, they resented their wives’ strike activity, which came at the expense of housework; even worse, women expected their husbands to do the housework. Women were frustrated, too, because their husbands refused to help at home and, more fundamentally, because men frequently forbade their wives to picket; some women came to resent that they were expected to have their husbands’ permission in the first place. The strike’s success in January 1952 rested on women strikers’ individual and collective bravery in the face of violence directed against the picketers, and on the ways that women and men negotiated the power relations in the family. Ultimately, union families redefined their community’s goals to include equality between men and women.

Yet another year later, in early 1953, women were still marching in circles on a picket line, but they were doing so on a movie set, on a ranch not far from the Empire Zinc mine. Blacklisted Hollywood filmmakers had joined the mining families to make a feature film that would tell the story of the strike, focusing on the conflict between husbands and wives. The Mine-Mill workers and their families played most of the roles and helped craft the screenplay. The product of this extraordinary collaboration, Salt of the Earth (1954), represented a spirited—though ultimately limited—resistance to domestic anticommunism, for both groups had ties to the Left and had suffered repression because of those ties. Many of Mine-Mill’s national leaders and a few of Local 890’s leaders belonged at one point or another to the Communist Party (CP), as did the blacklisted Hollywood artists who helped produce Salt. Making the film was their attempt to break through the isolation imposed by anticommunism. Re-enacting the strike through an artistic medium was also a way for the mining families to make sense of the changes caused by the strike. But union opponents and Hollywood anticommunists drew upon the political power of anticommunism to try, through violence and intimidation, to prevent the film’s completion.

For the miners, the Empire Zinc strike represented the culmination of a decade of union organizing around both workplace equality and civil rights for Mexican Americans. This upswing of Mexican American labor activism coincided with the downward turn in the fortunes of left-wing unions in the United States, and the juxtaposition of these two trends marks an important part of the history both of Mexican Americans and of the American Left. Because Mine-Mill worked for Mexican American labor and civil rights, Mexican American union members were to a great degree inoculated against the raging anticommunism that shaped the political culture and weakened the labor movement elsewhere. From a very different background came the Hollywood filmmakers. Already blacklisted from the movie industry for refusing to disavow communism, these filmmakers conceived of Salt of the Earth as an assault against the blacklist and the forces that gave rise to it. Independent movies that told “real stories about real working people” would not only break with conventional Hollywood storytelling but also show other filmmakers how to break out of the constraints of Hollywood studio contracts. The success in producing the film—and the failure in distributing it—show that leftists and working-class activists had some space to mark out an alternative to the emerging Cold War consensus, but not enough to give that alternative the power it would need to reshape the political and cultural terrain.

THE STRIKE

When the miners struck the Empire Zinc Company in Grant County, New Mexico, in October 1950, they believed that Empire Zinc was colluding with other mining companies in an ambitious effort to destroy the union. The strike, then, quickly became not just a test of Mine-Mill Local 890’s strength but also a conflict in which the union’s recent achievements in advancing Mexican American civil, as well as labor, rights were at stake. In meeting this high-stakes test, strikers drew on a heightened ethnic and class consciousness that they had developed over the 1940s.

Miners picketed uneventfully until June 1951, when Empire Zinc got a court injunction that forced the miners and their union to devise new strategies if they were to maintain the strike. Chief among these strategies was one proposed by miners’ wives: women would replace men on the picket lines, thereby obeying the letter of the injunction against picketing miners while defeating its purpose. In an unprecedented move, women took over the picket lines on June 12, 1951. And they held the lines for more than six months, until the Empire Zinc Company agreed to negotiate in January 1952. Miners won wage increases, other benefits, and improved housing conditions, and they considered the strike a victory.

But the strike proved important for more than labor-management relations and the survival of the union: women’s picket activity threw gender relations into confusion. On the picket lines women met violence from strikebreakers and law enforcement, while at home they encountered ambivalence—and sometimes outright hostility—from their own husbands. Pushed to the sidelines, many miners resented women’s picket activity because it threw into question their own work, their leadership, and thus, to a large degree, their manhood. Leaving the physical defense of the picket to women was bad enough. But actually taking over women’s household work, which the women could not perform while picketing, was even more emasculating. Yet that was precisely what their wives demanded. Women used the temporary inversion of the sexual division of labor to assert their independence as political actors and to challenge men’s authority in the household. Organizing shifts on the picket line, enduring jail time, holding the line against physical assault—all of these activities convinced many women that they wielded considerable power as a group and that they deserved their husbands’ respect as equals. Thus, the victory of the strike consisted also of forcing the union to take serious account of women’s place in the class struggle, for it revealed that women existed not at the margins of a struggle waged by men but as fully integral members of the working class.

THE MOVIE PRODUCTION

The Empire Zinc strike reverberated beyond the mining district in which it took place, helping to dismantle the dual-wage system of the American Southwest. But it would probably not have registered as more than a blip on the radar screen of American history had it not also found expression in Salt of the Earth. Blacklisted Hollywood filmmakers, enchanted by the story of the women’s picket, enlisted the mining families in an alliance to translate strike experiences into a dramatic film that could open cinema to realistic portrayals of working-class life. Mining families brought to the project more than their stories; they also collaborated on drafting the script, played most of the dramatic roles, and organized much of the off-camera production. The film, unique among movies of the period, connected women’s domestic labor with men’s “productive” labor in a way that presaged later feminist analyses of class and gender. The film’s production in Grant County represented an effort of unionists and blacklisted artists and technicians to render the blacklist impotent. For that very reason, it drew national attention from anticommunists, who were outraged that the blacklisted were still making films, and violent opposition from those Grant County residents who had opposed the union during the strike. Violence marked the production just as it had marked the strike itself, and the film only barely reached completion. This remarkable victory, however, was diminished since a coalition of anticommunists in the film industry, the American Legion, and even some trade unions prevented the film’s distribution.3 Feeding off the publicity generated by the movie, the federal government targeted Local 890 representative Clinton Jencks and others in Mine-Mill for criminal prosecutions that lingered in the courts for years. Salt of the Earth reached audiences only after the blacklist began to disappear in the 1960s. Today, half a century after it was made, Salt of the Earth is regularly cited as among the most important American films of the twentieth century.

A SYNOPSIS OF THE MOVIE

Salt of the Earth tells the story of a fictional Mexican American couple, Ramón and Esperanza Quintero, who live and work in Zinctown, a small New Mexican mining town.4 Ramón works for the Delaware Zinc Company and Esperanza works in the home. We quickly learn that there is tension between them, based on the different ways that they experience working-class life. Ramón enjoys meeting his friends in the beer hall, which Esperanza resents; Esperanza enjoys the radio, which represents to Ramón a degrading dependence on the installment plan by which they are paying for it. Esperanza, pregnant with their third child, heightens the differences between their worlds by comparing Ramón’s imminent strike with her imminent motherhood: “You have your strike,” she tells him. “I’ll have my baby.” Yet in contrasting their worlds, Esperanza also establishes the parity of obligations held by husbands and wives.

Their relationship registers the changes wrought by the strike. Ramón enthusiastically supports the strike as an expression of his own manhood and status as a breadwinner. The strike chokes off his paycheck (which distresses Esperanza, who must feed the family every day), but he adopts a longer view, in which life without the union would set them back even further. He recognizes, more readily than Esperanza does, that the union deserves credit for protecting Mexican American workers against Anglo discrimination, and this strike promises to win them equality with Anglo miners. But when women offer to take over the picket lines in order to circumvent “that rotten Taft-Hartley injunction,” Ramón opposes their proposal because he does not want to “hide behind women’s skirts.” Already angry that Esperanza votes against him in the union meeting at which the ladies’ auxiliary gets assigned to picket duty, he becomes even more distressed by the changes he soon finds in his home. With Esperanza away, he is suddenly forced to feed the children, wash the dishes, and hang the laundry, and he defends, ever more shrilly, his manly prerogatives in the home. For her part, Esperanza gradually transforms herself from a timid housewife into a vibrant labor activist, and she begins to stand up to her husband.

The conflict between Ramón and Esperanza mirrors the final confrontation between the mining community and the company. Convinced that the company will win out—partly because he overhears company discussions, partly because he cannot accept that women might win the strike—Ramón tells Esperanza that they cannot go on this way. He starts cleaning his rifle, set on joining his equally disgruntled friends on a hunting trip that would take them away from their assignment to the “standby squad.” By going hunting, the men would reassert their manhood by engaging in a quintessentially masculine activity and by defying a strike leadership that, they felt, had cast them aside. Esperanza believes that the hunt jeopardizes the strike: she senses that the company is on the verge of “something big,” and if the men were to leave, the company might pull it off. But Ramón has lost patience with the strategy of the women’s picket, and he seems willing to abandon it even if doing so means losing the strike. Esperanza, though, wants to win. Even more, she wants “to rise ... and push everything up” as she goes. “And if you can’t understand this,” she tells Ramón, “you’re a fool—because you can’t win this strike without me! You can’t win anything without me!” Ramón gets angry and grabs her shoulder, prepared to hit her: in this moment we see a history of male authority, enforced by the fist, met by Esperanza’s refusal to submit. “That would be the old way,” she tells him icily. “Never try it on me again.”

Ramón goes hunting with his friends. As Esperanza’s neighbor Teresa Vidal comments, “So they had a little taste of what it’s like to be a woman . . . and they run away.” But Ramón has a change of heart while walking in the woods, and he rallies his friends to return to town. And it is just in time, for the sheriff is at that moment evicting the Quinteros from their company-owned house. As union supporters pour in from all directions, Ramón finally recognizes the power of working-class solidarity, in which both men and women are indispensable. He and Esperanza quietly arrange for women to start bringing the furniture back into the house through another door, confounding the sheriff and his deputies. The community has a dramatic, tense showdown with the sheriff, and the sheriff backs down. The company representatives, watching from a safe distance, agree to settle the strike. Ramón’s long view of class solidarity has been refashioned to accommodate a closer view of the household and its critical place in the community.

HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE

The strike, the social history of the mining region in which it took place, and the film’s production and script have important things to tell us about the Mexican American working class, the Left, and gender in the twentieth century. The left-wing Mine-Mill union offered considerable space for working-class Mexican Americans to challenge ethnic and class inequality, first at work, then in local society and politics, and finally (along with left-wing Hollywood artists) in popular culture. Mine-Mill first appeared in Grant County early in the 1930s, a militant union increasingly close to the Communist Party and, as such, committed to interracial and interethnic organizing. Its efforts were part of widespread and heavily repressed Mexican American labor organizing in the Southwest and Midwest during the Depression, primarily by Communist-influenced labor unions.5 Mine-Mill stepped up its activity in Grant County in 1941, part of a southwestern organizing drive as the American economy geared up for World War II.6 Armed with an antiracist policy, Mine-Mill used the wartime labor shortage, the federal government’s official commitment to equality in defense-industry jobs, and the union’s patriotic no-strike pledge to organize Mexican American workers. If elsewhere, as other historians have shown, left-led unions scaled back their antiracist work in the name of all-out war production, in Grant County the two went hand in hand.7 Over the course of the 1940s, these workers and organizers collectively began to chip away at, if not eliminate, the dual-wage system in the southwestern mines. After World War II, Mine-Mill members and leaders also expanded the union’s mission to include addressing political and social inequality in the mining towns of Grant County.

The story of Local 890, however, was not solely a linear progression from oppression to liberation, or even overlapping and ever-widening spheres of union activity. Local 890’s strength was tempered after World War II by the domestic Cold War, when mining managers, eager to reassert their power, confidently wielded the club of anticommunism in labor disputes. Mine-Mill was one of eleven unions expelled from the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1949 and 1950 for inadequately ridding themselves of communist influence. But in order to understand the local political economy, it is important to reject any easy or apparent symmetry between communism and anticommunism; both were present in Grant County in the late 1940s, but they do not line up evenly in opposing columns. Instead, we find a confusing political terrain in which one version of communism—an especially democratic one—influenced Local 890’s structure and actions but could not be openly acknowledged, while anticommunism was used by management as one tool among many in what was essentially an economic contest. Some Local 890 members and leaders belonged to the CP, finding in it a powerful tool for pressing working-class and Mexican American claims. Significantly, the party organized married couples, thus building into its very structure a recognition of women’s importance to the class struggle. But despite these complexities, in the discourse of anticommunism, communists were single-minded, uniform, implacable, and devious, insinuating themselves into legitimate institutions and committing unsuspecting members to a program that subverted American democracy. Communist unions were controlled by Soviet agents and served Soviet masters. There was no room in this picture for a left-wing union to be democratic or genuinely to represent the interests of its members. Ironically, the searchlights that regularly swept the nation in the late 1940s and 1950s in order to expose communism failed to throw light on the real meaning of leftist democratic unionism precisely because they forced all progressives to hide any connections to the CP.

Anticommunists were correct, however, in perceiving a threat to the social order: Mexican American miners were threatening to step out of their proper place. In this respect, the miners were part of a wider tradition of Mexican American labor and civil rights activism whose groundwork was laid in the 1930s by left-wing unions and by civil rights organizations like the radical Congreso Nacional del Pueblo de Habla Española (National Congress of Spanish-Speaking People) and the moderate League...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- On Strike and On Film

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Maps and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Grant County’s Mining District

- Part I Crisis

- Part II The Women’s Picket

- Part III A Worker-Artist Alliance

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index