![]()

1

For He Looks upon You as Foolish Children

Captives, Slaves, and Prisoners of the Red Atlantic

The late Jack Forbes, in his provocative book Africans and Native Americans, notes a curious incident reported by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historiae on the authority of Cornelius Nepo. Pliny states that Quintus Metellus Celer, who was a colleague of Lucius Africanius in the consulship of Rome, while in Gaul received the gift of “Indos,” “who on a trade voyage had been carried off course [from India] by storms to Germany,” from a Germanic chieftain.1 Forbes says that the event, which would have taken place around 60 B.C.E., and the presence of Indians in Germany would have been explicable to Pliny because he believed a sea connected the Indian Ocean with the Baltic. Such a waterway is, of course, fictitious. Forbes writes, “We know, however, that the only way people looking like ‘Indians’ could have been driven by a storm to northern Europe would have been across the Atlantic from America.”2 He speculates that these might have been Olmecs or “the builders of Teotihuacan.”3

There is much reason to doubt Pliny’s account. His ethnographic materials are largely fantasy. And Forbes overlooks that it was Columbus, more than fourteen centuries later, who labeled Western Hemisphere indigenes “Indians” because he thought he had reached the Indies. If we discount wish fulfillment or fanciful speculation, the first indigenous North Americans to reach Europe were almost certainly Beothuks (or members of an ancestral population thereof), and like Pliny’s and Forbes’s “Indos,” they were captives.4

They were merely the first of over thousands upon thousands of Western Hemisphere indigenes to become captives and slaves. These Natives would find their way to Iceland and Norway, England, France, Portugal, Germany, Bermuda, the Caribbean and other islands off the Americas, and even North Africa, among other far-flung destinations.

Two Beothuk Boys

Leif Erikson sighted the northern coast of North America in approximately 1000 C.E., calling it Vinland. Shortly thereafter, around 1003, the Vikings founded a settlement in present-day L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland. They encountered “Red Indians” (as distinguished from the Inuit), whom they called skrælings, an archaic word of uncertain meaning but commonly assumed to mean something like “wretches.” These meetings are recorded in the Icelandic sagas.

According to the Grænlendinga Saga, encounters with the Natives were initially friendly. Despite the language barrier, trade was opened, but the relationship soon turned hostile.5 In Eirik’s Saga, we learn that Leif’s brother Thorvald was struck in the groin by an arrow in one skirmish with skrælings. As he pulls the arrow out, he poetically and tragically says, “This is a rich country we have found; there is plenty of fat around my entrails.” Then he expires—nobly.6

Controversial historian Jayme Sokolow summarizes: “The Vikings treated the Skraelings as they would any other outsiders. When the opportunity arose, they killed the adults and enslaved their children. On other occasions, they traded bolts of red cloth for furs.”7 After Thorvald Erikson’s death, the Vikings fled. They spotted five Natives, “a bearded man, two women, and two children.”8 Though the adults manage to escape, Thorfinn Karlsefni and his men captured the boys, whom they took with them. The boys were taught Norse and baptized.9 Thus in 1009, Indian captives were taken to Norway (and perhaps Iceland).10

The names of these boys forcibly orphaned are not recorded, but those of their mother and father are: according to the sagas, the children identified them as Vætild and Ovægir, respectively. Jennings Wise and Vine Deloria Jr. say that the boys were christened Valthof and Vimar.11

Continuing conflict with the skrælings convinced Karlsefni of the futility of attempting a permanent settlement in North America. According to Gwyn Jones, “His numbers were small, and their weapons inadequate. They were unwilling to woo and unable to conquer.”12 The fact that they took the boys and taught them their language is strong evidence that they intended to continue trading with the region’s indigenous people. Valthof and Vimar would be able to serve as interpreters. Such abductions became an established strategy in this regard.

The penultimate chapter of the Grænlendinga Saga begins, “Now there was renewed talk of voyaging to Vinland, for these expeditions were considered a good source of fame and fortune.”13 Annette Kolodny writes, “Obviously, the potential threat posed by the Native population has not dissuaded some individuals from further expeditions, although there is no longer any suggestion at attempting a permanent colony.”14 The Vikings “continued visiting the North American coast in search of timber and furs, but after 1300 the climate grew colder and travel became more difficult.”15 Eventually they ceased entirely. Around 1350, the Vikings abandoned the Western Settlement in Greenland, and by 1500, settlement on that island ceased entirely. By then, however, Greenland’s days as a jumping-off point for North American exploration were long in the past. The last record of a specific voyage to Vinland was that of Bishop Eirik (probably Eirik Gnupsson) in 1121, and we do not even know if he reached it successfully.16 According to Dutch anthropologist Harald Prins, however, there is “an intriguing historical snippet” about a large canoe that Newfoundlander Natives were putting into port at Lubec in 1153. Prins concludes that, if the incident happened at all, both Natives and canoe most probably came on a Viking knarr.

Years later, circa 1420, Inuit captives were taken to Scandinavia. Their kayaks were displayed in the cathedral at Tromsø, Norway. In 2010, DNA analysis of contemporary Icelanders revealed a strain of mitochrondrial DNA most closely associated with Amerindian populations. This so-called C1 lineage is carried by more than eighty Icelanders, and church records have permitted researchers to trace the specific substrain (or subclade), known as C1e, to four women from shortly before 1700, though they believe it arrived much earlier. C1e has been found only in Iceland and does not match Greenlander or any other Inuit population. Nor does it precisely match any modern Native population. Since mitochondrial DNA is passed down only through the female line, the logical conclusion is that it entered via a woman from some now extinct Amerindian lineage. The Beothuk, the last of whom died in 1829, would seem the likely candidate. Razib Khan, a science writer for Discover, writes, “Perhaps the Europeans had enslaved a native woman, and taken her back to their homeland when they decamped? But more likely to me is the probability that the Norse brought back more than lumber from Markland, since their voyages spanned centuries.”17 It is certainly possible; grabbing a few North American indigenes quickly became a standard operating procedure of European sailors, and the Vikings certainly had a reputation for being rapacious.

Though Valthof and Vimar may have become the first Amerindian cosmopolitans, the Vikings departed for their homelands and left no continued colonial presence in North America. Their clashes with the Natives and their capture and kidnapping of the two Beothuk boys, however, established the pattern of European interaction with the continent’s indigenes that would be replicated many times over. That information undoubtedly traveled from tribe to tribe beneath the Fall and beyond through trading networks. The seeds of distrust and knowledge of settler violence and indigenous captivity were sown from Newfoundland to Florida. Unfortunately for the next people to be “discovered” by explorers from Europe, they were not part of the trade routes that would have carried word of the “skrœlings’” difficulties with such people.

A Man Obsessed I

Christopher Columbus was a man of consuming personal ambition. He was also a man of many obsessions. These two aspects of his personality were symbiotic. His ambition drove him to multiple obsessions. And, in turn, the objects of his obsessions became, he believed, the means to fulfill his ambitions.

Born Cristoforo Columbo in or near Genoa on the Italian coast, he was the son of a weaver. Little reliable is known about his childhood, but it seems he went to sea at a fairly early age, alternating between voyages on the Mediterranean and periods onshore, working for his father. Without formal education, he became an autodidact, reading and internalizing the travel accounts that were popular at the time. Seven of the books he owned survive. These include Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historiae with its travelers’ tales and fantastic ethnographies, Marco Polo’s exaggerated report of his journey to China, and Pierre d’Ailly’s Imago Mundi. Published in 1410, the last of these, written by a French cleric, was an imaginative, pseudo-scientific cosmography.18 Such works fueled Columbus’s imagination and his desire to travel to exotic locales. D’Ailly’s book in particular influenced him. D’Ailly suggested the possibility of reaching Asia by sailing west from Europe. Columbus’s copy is filled with the sailor’s marginalia.

The myth that surrounds Columbus claims that he was among the first to believe that the world was round. Others feared sailing west for fear of falling off the edge of a flat earth. Such tales are the product of modern childhood stories and grade school textbooks. In truth, most educated people at the time knew the earth was round. Sailors were merely reluctant to sail west into a vast, open Atlantic. Yet writers like d’Ailly fixed Columbus’s obsession to reach the Indies, Japan, and China by sailing west. His fixation led to his “discovery” of the Americas and the re-inauguration of the Red Atlantic.

Columbus’s second obsession, less peculiar to himself, was gold. In a letter to Father Martinez, Paolo Toscanelli urged the priest to let the Portuguese king know how profitable an undertaking a voyage to Asia would be: Japan, he said, was rich in gold. As noted in the introduction, one need only read Bartolomé de Las Casas’s Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies to get a sense of the place indigenes’ gold held in the minds of later Spanish explorers and conquistadores. All came in search of the wealth of the Americas. For Columbus, there was a special urgency. In exchange for the Catholic Monarchs’ investment in his enterprise, the mariner had promised them riches beyond measure. In return, they had promised him 10 percent of the wealth brought from Asia along his new route, not only by himself but by anyone and not only in his lifetime but to his heirs for all future time. Some obsession is understandable.

On October 12, 1492, Columbus set his first dry foot on Western Hemisphere land on what is today commonly assumed to be Watlings Island in the Bahamas. Columbus’s original log of that first voyage was lost. What we have is an abstract of it produced by Las Casas some forty years after the Admiral’s death. In that document, commonly called the Journal of the First Voyage to America, the narrator is sometimes Las Casas and sometimes Columbus himself, whom Las Casas quotes. We also have a letter that Columbus wrote, reporting on his journey, after his arrival at Lisbon in March 1493.

Stepping ashore, Columbus called the men in his landing party together “to bear witness that he before all others took possession (as in fact he did) of that island for the King and Queen his sovereigns, making the requisite declarations.”19 In his letter addressed to the royal treasurer Luis de Santángel, Columbus himself describes the incident and others like it: “I came to the Indian sea, where I found many islands inhabited by men without number, of all which I took possession for our most fortunate king, with proclaiming heralds and flying standards, no one objecting.”20 He named the place San Salvador for the Holy Savior. Seemingly conveniently for Columbus, as he was completing his legalistic rituals of discovery, according to Las Casas, “Numbers of the people of the island straightway collected together.”21 Of the encounter, the Admiral declared, “As I saw that they were very friendly to us, and perceived that they could be much more easily converted to our holy faith by gentle means than by force, I presented them with some red caps, and strings of beads to wear upon the neck, and many other trifles of small value, wherewith they were much delighted, and became wonderfully attached to us.”22

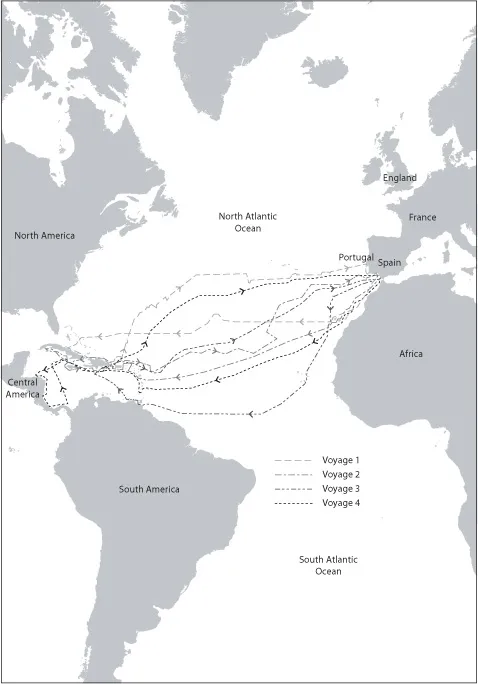

The Voyages of Columbus

The people who gathered around Columbus on the beach as he claimed their land for the Spanish crown were the Taino, who called the island Guanahani. By the time they set eyes on the Spanish seamen, they were themselves old hands at plying the Atlantic. The Taino are also called the Island Arawak to both relate them to, and distinguish them from, the Arawak who reside in northeastern South America. Sometime around 500 B.C.E., Archaic Taino—the ancestors of those whom Columbus would meet—split off from their non-seafaring Arawak relatives and set forth on the Caribbean. By 900 C.E., they occupied the Greater Antilles islands of Cuba, Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Jamaica, and Puerto Rico and the southern part of the Bahamas. They routinely used their large dugout canoes to travel between islands.23

There is no record of what Columbus said to the curious Indians who crowded around him on that beach on Guanahani. An educated guess, however, is that the first confusing words the indigene heard this white man utter were “Salaam aleichem,” the standard Muslim greeting, translated a...