- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In a detailed study of life and politics in Philadelphia between the 1930s and the 1950s, James Wolfinger demonstrates how racial tensions in working-class neighborhoods and job sites shaped the contours of mid-twentieth-century liberal and conservative politics. As racial divisions fractured the working class, he argues, Republican leaders exploited these racial fissures to reposition their party as the champion of ordinary white citizens besieged by black demands and overwhelmed by liberal government orders.

By analyzing Philadelphia’s workplaces and neighborhoods, Wolfinger shows the ways in which politics played out on the personal level. People’s experiences in their jobs and homes, he argues, fundamentally shaped how they thought about the crucial political issues of the day, including the New Deal and its relationship to the American people, the meaning of World War II in a country with an imperfect democracy, and the growth of the suburbs in the 1950s. As Wolfinger demonstrates, internal fractures in New Deal liberalism, the roots of modern conservatism, and the politics of race were all deeply intertwined. Their interplay highlights how the Republican Party reinvented itself in the mid-twentieth century by using race-based politics to destroy the Democrats' fledgling multiracial alliance while simultaneously building a coalition of its own.

By analyzing Philadelphia’s workplaces and neighborhoods, Wolfinger shows the ways in which politics played out on the personal level. People’s experiences in their jobs and homes, he argues, fundamentally shaped how they thought about the crucial political issues of the day, including the New Deal and its relationship to the American people, the meaning of World War II in a country with an imperfect democracy, and the growth of the suburbs in the 1950s. As Wolfinger demonstrates, internal fractures in New Deal liberalism, the roots of modern conservatism, and the politics of race were all deeply intertwined. Their interplay highlights how the Republican Party reinvented itself in the mid-twentieth century by using race-based politics to destroy the Democrats' fledgling multiracial alliance while simultaneously building a coalition of its own.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Philadelphia Divided by James Wolfinger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

II World War II

4 The Crucible of the Home Front

Men accustomed to power and giving unquestioned commands must realize there is a war going on—a war for freedom of opportunity; not for the powerful few, not for white, yellow, brown or black, but for everyone of the teeming masses of India, Europe, Africa, Australia, yes—even our own Negro Americans.

—Carolyn Davenport Moore, 1943

William Seymour watched the black family move in across the street in his North Philadelphia neighborhood and believed he knew what had to be done. Luther and Juanita Green were not necessarily bad people. In fact, Seymour did not even know them. But to Seymour and his neighbors, the Greens represented all of the African Americans trying to move into white neighborhoods. Long-time residents of this stretch of North Thirteenth Street had watched nearby blocks turn black almost overnight, and they refused to accept such a development. So on March 16, 1942, their campaign of intimidation began. Seymour first grabbed Mrs. Green on the street and, in her words, told her “that no ‘n—r’ would be allowed to stay there and he would see that they were made miserable.” The next day an elderly woman barged into the Greens’ house and told them they should save themselves the trouble and get out now. “No n——s,” she said, “are going to stay [here], ruining a good neighborhood.” That night, as the Greens entertained guests, they heard noises in the street. A second later, bottles of paint slammed into the front of the house and through the front windows, coating everything. Then the attackers doused the streetlights and fired forty shots into the Greens’ home. Luckily no one was hurt in the barrage, and Luther Green slipped out the back door to get the police. It took over twenty minutes for the squad car to arrive, and the officers could barely control the mob collecting in the Greens’ front yard. As a policeman moved to the front door, several people stormed the house, yelling, “Lynch them!” The officers managed to stop the attack and got everyone to go home, but for a time the Greens feared they would be the victims of a race riot.1

The city's response to the attacks reinforced African Americans’ ambivalence about Philadelphia's legal and political systems. On the one hand, police arrested Seymour, his wife, and two other rioters on charges of trespassing, vandalism, and disorderly conduct. The presiding magistrate, an African American named Ed Henry, took the charges seriously, lecturing the defendants on Christian love, and then ordered them held for trial on bail ranging from $500 to $2,500. A jury later convicted Seymour and one of his accomplices of inciting a riot, and black commentators generally found the outcome measured but appropriate. On the other hand, black groups, including the NAACP and the Black Elks, formed a coalition to ask police officials why their patrolmen took twenty minutes to respond to a riot. The group also wanted to know why policemen took the Greens to a nearby friend's house for their safety but left them standing on the doorstep when the friend was not home. The police offered no satisfactory answers, so the coalition went to the Republican mayor, Bernard Samuel. He brusquely told representatives he would “make a thorough investigation of the occurrence” and then sent them away. The riot and later treatment of black leaders led the Philadelphia Tribune to demand, “What kind of people do the citizens in the neighborhood of 2323 north 13th street think we are anyhow?” “We say it here and now,” the editors continued, “the point is rapidly being reached where colored people will stop thinking that peace is a virtue; and when it does come our tormentors will rue the day they were born.”2

The events of March 1942 highlight developments critical to understanding Philadelphia's history during World War II. The arrival of tens of thousands of war workers placed enormous strains on the city's housing market. With a public housing program that had utterly failed to meet the city's needs in the 1930s and a private sector with no desire to build for poorer people, Philadelphia faced a desperate situation in trying to house its growing population. Private neighborhoods like the Seymours’ block in North Philadelphia and public housing projects became scenes of clashes between Euro- and African Americans who competed for limited housing in the city.

Housing, however, was only one pressure point in a city the fbi described as one of the most racially tense in America. Job discrimination also created ill will between Philadelphia's Euro- and African American populations. Jim Crow in the city's unions, its places of employment, and the agencies of its municipal government angered blacks. In the midst of a war for democracy, with so much talk of freedom and the horrors of Nazi racist ideology, discrimination in one of the nation's largest war-production centers, a northern one at that, galled African Americans. They could not understand how early in the war signs on factory gates changed from “No Help Wanted” to “Help Wanted: White.” Surely if ever they could press their claims for equality and inclusion, African Americans believed, World War II was the time.3

As the African American population rose and placed greater demands on the city's housing and job markets, any cross-racial alliance of ordinary people strained to the breaking point. Blacks, it seemed to many Euro-American workers, were increasingly assertive, demanding access to jobs that had always been “white” and calling for an end to discrimination in the city's neighborhoods and housing projects. This assertiveness worried many whites, particularly Italian and Irish Americans, and the Republican Party capitalized on their fears. By the World War II era, the Philadelphia gop had learned that race was the weak point in the Democratic Party's coalition of voters, and Republican candidates developed political appeals to exploit that vulnerability.

Private Housing

Like every industrial center in the nation, Philadelphia saw tens of thousands of people enter its environs during World War II. After a decade in which the city proper had actually lost population, the influx of nearly fifty thousand newcomers overwhelmed the housing market. Whatever their race, people were faced with a dire shortage of homes. Philadelphia Housing Association officials could find only 5,334 vacant units in the entire city in 1940, and that was before the in-migration really began. The situation would only worsen, they believed, until it would “be virtually impossible for workers to move to the area of their employment.” In all, private and public builders produced only twenty-four thousand homes from 1941 to 1943, which led to such an acute shortage that the housing association reported, “Houses [were still] in the market, which … should have been demolished.”4

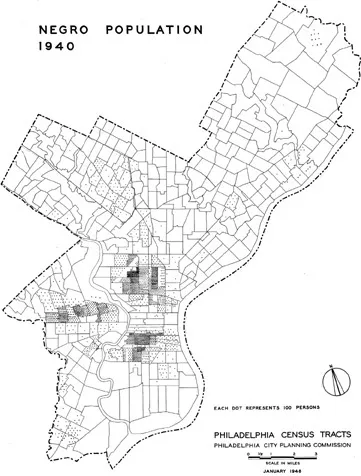

Although housing was a widespread problem, the burden fell especially hard on African Americans. Whereas more than three-quarters of all white homes conformed to what the housing association termed “minimum standards” (indoor plumbing, no need for major structural repairs, and the like), only 46 percent of black homes met the criteria. Moreover, 10 percent of blacks but only 2 percent of whites lived in overcrowded housing. Even those African Americans who had enough money to buy a decent home had few if any options open to them. Private builders openly discriminated, offering only seventy-four new homes for sale to blacks from 1940 to 1944. In the existing stock, African Americans met determined resistance from people like the Seymours all over the city. Blacks found themselves boxed in. Barred by segregation from living in both new and old neighborhoods, they were forced to live in the city's oldest, most overcrowded areas. Small wonder former NNC leader Arthur Huff Fauset wrote, “Once it could be said that Philadelphia was the city of homes. Today it would be more nearly correct to point to it as the city of slums.”5

MAP 3. Distribution of Philadelphia's African American population, 1940. The growing density of the black population in the World War II era was particularly noticeable in North Philadelphia. Courtesy of Philadelphia City Planning Commission. ©1940 City of Philadelphia. All rights reserved.

African Americans refused to accept the situation. They knew the nation needed their support during the war, and this gave them new openings to press their claims. Even more important, the black community had become more activist as a result of the ferment of the 1930s, and black Philadelphians were thus better prepared to capitalize on the new context. The Youth Committee for Democracy and the NAACP spearheaded the push to improve black housing. The Youth Committee was an organization of young Philadelphians who pressed for progressive causes with the support of black institutions, such as the Catherine Street YWCA, the Philadelphia Tribune, and various churches and civic organizations as well as left-leaning unions, including the ilgwu and the Hod Carriers. Youth Committee members argued that the war era had led to increased segregation in the city. Their studies found that the population of the three main black districts in North, South, and West Philadelphia had increased by forty-two thousand people while other parts of the city had lost twelve thousand African American residents. Their studies also documented the terrible living conditions and Jim Crow barriers that blacks faced in the housing market. The committee concluded by warning Philadelphians that “an explosive situation is developing,” and the only solution was government intervention. To spur authorities, they urged people to use letters and petitions to “put immediate pressure on the Philadelphia Housing Authority.” But it was important, they argued, to go beyond individual action because only group protests could energize the entire community and bring about real change. “Ministers and churches should focus public attention on the festering sore of racial discrimination,” they said. “Race relations groups should [also] organize militant forms of action. If we need to picket City Hall, let's prepare to picket. If we can arouse city and federal authorities by parading down Broad Street, let us lay plans now for such a parade.” Then, in a none-too-subtle warning to city leaders they wrote, “The Philadelphia-Chester area has racial problems very similar to those in Detroit, Mobile, and Los Angeles. Will nothing be done here until the rioting spreads to Market Street?”6

The local NAACP lent greater weight to the Youth Committee's protests. Created in the 1910s, the Philadelphia NAACP had never had much of a following in the black community. Most African Americans regarded it as the preserve of a few socialites who held little interest in the problems of ordinary people. The Depression had done nothing to alter this view, and membership numbers had dropped so low that national NAACP leaders wondered if the branch would survive. But in the 1940s new leaders—Executive Secretary Carolyn Davenport Moore and President Theodore Spaulding—invigorated the chapter, involving it in campaigns to end discrimination in the housing and job markets and to stop police brutality. These campaigns established the branch's credibility and showed that it would press the government for black rights.7

From the start of her tenure in September 1942, Moore made it clear that housing would be a top priority for the organization. In one of her first official acts she helped James Walker, an African American who had the deposit he placed on an apartment returned due to discrimination. Moore and other NAACP members investigated the bank that owned the apartment house, some of the tenants, and even the local Catholic Church. In a news release, Moore told the public that Walker, a World War I veteran and steadily employed machinist, had lost his home because, in the words of the bank's representative, his institution did not want “the unfavorable public reaction … for permitting the first Negroes to enter the block.” The NAACP also challenged the Catholic Church to live up to its Christian creed while at the same time giving African Americans another place to focus their anger. “The strongest opposition to [Walker's] tenancy,” Moore wrote, “comes from the Church of the Most Precious Blood of Our Lady … [the] priest there is the Rev. J. P. Green.” On another occasion, Moore helped put together a committee to protest prosegregation meetings held on city property in southwest Philadelphia. “The express purpose [of the meetings],” she wrote, was to “arouse the citizenry against permitting a Negro minister to occupy a property which had been purchased for him in an otherwise ‘all-white’ block.” Blacks could not tolerate this activity on public grounds, she argued, and her committee asked the mayor to issue an order that city property would no longer be used “for the purpose of inciting one group against another.” Mayor Samuel, in a pattern that became increasingly clear throughout his tenure, refused to act. Nonetheless, such activities showed that ordinary African Americans now had the NAACP as an ally in the battle against discrimination.8

Public Housing

While the NAACP put some effort into the private housing market, the organization reserved most of its energy for the campaign to build more, and desegregate all, federal housing. This campaign fit squarely into a liberal mindset that believed only federal assistance, as Moore put it, could provide relief for “the hundreds of colored families who have been unable to find housing in this area.” Private real estate interests, however, made public housing a problem from the start. Although the Philadelphia Housing Authority had members from government, private housing, and labor, conservatives dominated and as a rule rejected federal aid. “Private enterprise—not the public authority—should build defense housing,” announced Raymond Rosen, a businessman and PHA board member. Some federal officials agreed. Acting Regional Defense Housing Coordinator B. Frank Bennett met with the Philadelphia Real Estate Board and then formed a committee to cater to their interests. The Bennett Committee, made up primarily of businessmen along with two labor representatives, took over much of the work of the PHA for a time and agreed to ban government housing “except as a last resort.” Moreover, conservatives wanted any government construction to be temporary and cheap. This meant small, drafty, unattractive homes built of comp-board (compressed paper) on concrete slabs and heated by oil or wood stoves. No one with other options would live in such a place, and real estate companies were thrilled to know they would not face real government competition. The two union men on the committee angrily resigned, saying, “Merchants and businessmen … [are] sabotaging the [housing] program … We don't want any cardboard homes here.” City officials listened to the conservative interests instead of the labor leaders and turned down $19 million in federal housing funds while building only a little over 4,000 units, despite the fact that planners had called for 10,000 publicly built homes. Most of the homes that did get built were temporary and strikingly unattractive.9

For African Americans, the most galling aspect of the city's limited federal housing was the continuation of racial segregation in the projects. While blacks had access to the prewar Johnson Homes, many of the new projects, even the temporary ones, were either designated for whites only or had quotas for black occupancy. Such an arrangement was unacceptable to the NAACP because the Johnson Homes were far from any war plants, and African Americans had no access to housing closer to the city's better jobs. NAACP officials discussed the situation numerous times with PHA officials, but after what Moore called “months of pointless conversation and bickering” it became clear to her that the authority did not “have the interest of Negro defense workers at heart.” Further meetings obviously would not resolve the situation, she believed, so she and other NAACP leaders urged black workers to protest to the PHA and demand adequate housing since they were “contributing to the ultimate defeat of the Axis.” The Pittsburgh Courier termed Moore's call for activism an “all out campaign,” and the pressure eventually led government officials to grudgingly open four more projects to black occupancy.10

The stories of two of these projects highlight how race influenced the city's housing policies and how Euro-Americans responded differently to black public housing depending on the level of alleged threat it posed to white neighborhoods. The government had begun building the Richard Allen Homes in the heart of North Philadelphia's growing black community before the war started. The project was specifically intended for poor African Americans who had lived in the area before the city demolished their homes as part of a slum clearance program. Like the popular Johnson project, the Allen Homes inspired great hope among poorer blacks, and over four thousand families applied for the thirteen hundred units when the complex opened in 1942. Ov...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Philadelphia Divided

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations, Maps, and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- I The New Deal Era

- II World War II

- III The Postwar City

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index