- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Indigenous allies helped the Spanish gain a foothold in the Americas. What did these Indian conquistadors expect from the partnership, and what were the implications of their involvement in Spain’s New World empire? Laura Matthew’s study of Ciudad Vieja, Guatemala — the first study to focus on a single allied colony over the entire colonial period — places the Nahua, Zapotec, and Mixtec conquistadors of Guatemala and their descendants within a deeply Mesoamerican historical context. Drawing on archives, ethnography, and colonial Mesoamerican maps, Matthew argues that the conquest cannot be fully understood without considering how these Indian conquistadors first invaded and then, of their own accord and largely by their own rules, settled in Central America.

Shaped by pre-Columbian patterns of empire, alliance, warfare, and migration, the members of this diverse indigenous community became unified as the Mexicanos — descendants of Indian conquistadors in their adopted homeland. Their identity and higher status in Guatemalan society derived from their continued pride in their heritage, says Matthew, but also depended on Spanish colonialism’s willingness to honor them. Throughout Memories of Conquest, Matthew charts the power of colonialism to reshape and restrict Mesoamerican society — even for those most favored by colonial policy and despite powerful continuities in Mesoamerican culture.

Shaped by pre-Columbian patterns of empire, alliance, warfare, and migration, the members of this diverse indigenous community became unified as the Mexicanos — descendants of Indian conquistadors in their adopted homeland. Their identity and higher status in Guatemalan society derived from their continued pride in their heritage, says Matthew, but also depended on Spanish colonialism’s willingness to honor them. Throughout Memories of Conquest, Matthew charts the power of colonialism to reshape and restrict Mesoamerican society — even for those most favored by colonial policy and despite powerful continuities in Mesoamerican culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Memories of Conquest by Laura E. Matthew in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Indigenous Invasions

Mexicans & Maya from Teotihuacan to Tollan

Why do all the invaders come from the north?

—Guatemalan graphic artist José Manuel Chacón, aka Filóchofo, La otra historia (de los mayas al informe de la Comisión de la Verdad) (1999)

One could logically begin an account of the Mexicanos of Ciudad Vieja with the sixteenth-century invasion of Guatemala. This, in fact, is where the colonial-era Mexicanos often started their own story. But their history belongs not to colonial New Spain, much less to the modern nation-states of Mexico or Guatemala, but to Mesoamerica as a whole. Trade, diplomacy, war, and conquest connected those whom we might carelessly label Mexicans and Maya long before the Spanish arrived on the scene. Such connections shaped that violent meeting and what followed.

Multiple volumes have attempted to unravel ancient relationships across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec during the first millennium and a half A.D. Very often, people from the Gulf coast or the Basin of Mexico are depicted as dominant players. Some scholars of ancient Mexico, especially in the 1970s and 1980s, suggested that the central Mexican city of Teotihuacan created a Mesoamerican empire in the fourth century A.D. that overshadowed Maya civilization. Others have claimed that the Classic Maya learned the craft of state-building from their Mexican counterparts and have attributed the traditions reflected in famous colonial-era texts like the K’iche’ Maya Popol Wuj and the Yucatec Maya Books of Chilam Balam either to Mexican invaders of highland Maya territory in the thirteenth century or to Mexicanized Maya of the Gulf coast region led by central Mexican rulers. On the opposing side (because people studying Maya history often felt compelled to defend their academic territory), ancient Maya rulers were portrayed selectively adopting certain Mexican styles of architecture and religious symbolism while remaining thoroughly Maya. Some have argued that the Maya had a greater influence on Mexican polities than the other way around.1 Many of these ideas, and the resulting sharp dichotomy between Mexican and Maya, have been complicated by recent work in Mesoamerican archaeology and epigraphy. But the Mexican/Maya dichotomy lives on despite scholarly qualifications. Since this book could be read as an account of Mexican peoples who invaded highland Maya areas in the sixteenth century, it is worth sorting out whether the Spanish conquest of 1524–28 was, from a Mesoamerican perspective, just the latest invasion of Maya territory by people from the west and north.

In Guatemala at the time of this writing, it is widely accepted on the basis of the aforementioned academic debates that some of the most numerous and politically active Maya groups today, such as the K’iche’ and the Kaqchikel, have Mexican or “Toltec” heritage. Opponents of indigenous rights movements in Guatemala have used this notion to argue that the K’iche’ and Kaqchikel and others like them are not truly Maya, but Mexican or a Mexican-Maya hybrid. An extreme example comes from a 2005 newspaper editorial decrying the lack of attention to those suffering from Hurricane Stan, in which columnist Jorge Palmieri noted, in an aside, that the K’iche’ “say they are descendants of the Maya, but it is known that they descend from the Toltecs who integrated themselves into the Spanish troops captained by the bloodthirsty Pedro de Alvarado after he killed around 25,000 Aztecs in Tenochtitlan.”2 A 1997 article in the cultural magazine Crónica expressed the same idea in more muted tones. Ricardo Sotomora von Ahn—arguing for national unity around the notion of being, like the United States, a nation of immigrants—wrote that “although indigenous people are trying to revive their Maya heritage, it is widely known that when the Spanish conquistadors arrived at Guatemala, the principal tribes like the K’iche’s and Kaqchikeles were dominated by elite priest-warriors who . . . were ethnically Toltecs.”3

By these arguments, the K’iche’ and Kaqchikel cannot claim pure descent from the much-romanticized Classic Maya, whom commentators (echoing both colonial and neocolonial racial theories) say disappeared and left only the most degraded remnants to be dominated by the Mexican invaders. Nor can they claim rights as indigenous peoples, since as the descendants of foreign (i.e., Mexican) invaders and native Maya, they are no different from Ladinos of European, African, or Asian heritage who may also have mixed with the Maya or other Mesoamericans. Palmieri goes further, equating the allegedly Toltec Maya with the Nahua allies who invaded Guatemala alongside the Spanish in the sixteenth century—the very subjects of this book. From both a modern political perspective and a historical one, it is important to clarify: Who exactly were the Toltecs? Are they the same as the Mexicans or the Aztecs? When did they first arrive in Guatemala, if ever, and what was their relationship to the Maya? Understanding the invasion of Maya territory by peoples labeled “Mexicanos” in the sixteenth century requires us not to bypass centuries of previous Mexican-Maya interaction, nor to use broad ethnic labels like “Mexican” and “Maya” thoughtlessly.

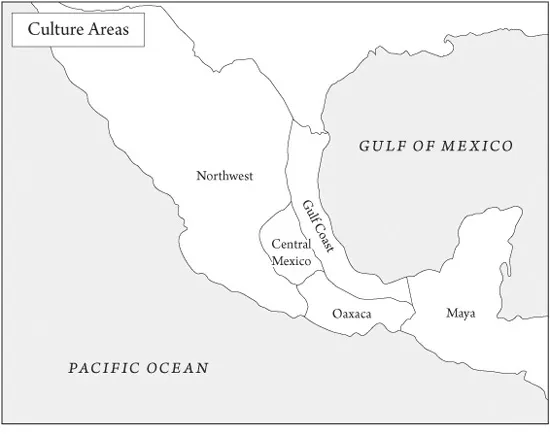

The first premise of this book, then, is that the Ciudad Vieja Mexicanos’ history is not merely colonial, but must be situated within a much longer, profoundly Mesoamerican past. Geographically bounded by the limits of agriculture in modern Mexico to the north and the border between modern Nicaragua and Costa Rica to the south, Mesoamerica is home to an extraordinary diversity of peoples who nevertheless share a common cultural base. To a great extent, Paul Kirchhoff’s 1943 definition of Mesoamerica as a civilization connected by a broadly shared culture and history still stands.4 All Mesoamericans have depended for over 3,000 years on the cultivation of maize, beans, squash, and chile peppers; have maintained a complex system of astronomy and calendrics that links the circular movement of the planets and stars to cosmic cycles of creation and destruction; and have based their spatial and social organization on the four cardinal points. Ancient Mesoamericans developed hieroglyphic writing on folded paper, deerskin, and monumental stone stelae, played their famous ball game on sanctified courts, and honored the cycles of life, death, and rebirth through bloodletting and human sacrifice. Archaeologists have located the oldest traces of this uniquely Mesoamerican culture in modern-day Veracruz and Oaxaca. Not surprisingly, a major geographical and cultural boundary occurs precisely at this point: the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a land bridge stretching from the Pacific coast of Oaxaca to the Gulf coast of Tabasco and Campeche, Mexico.

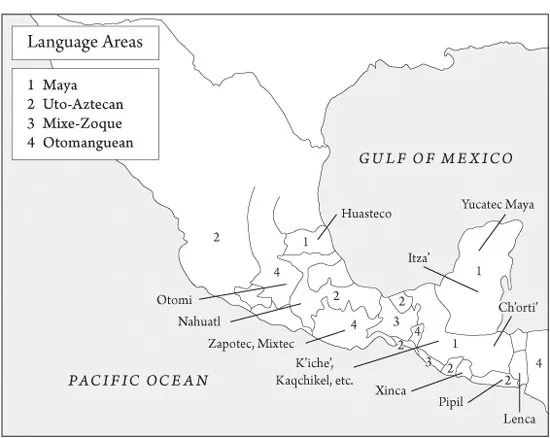

In popular and some generalist scholarly writing in English, the peoples living west of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec are commonly labeled “Mexican” and those living to the east and south, “Maya.” Both labels emerged during the colonial period, primarily as Spanish administrative tools. “Mexican” originally comes from the Mexica Tenochca, leaders of the Aztec empire centered on the city of Tenochtitlan. For the colonial-era Spanish, mexicano most specifically referred to this group of people or those affiliated with them. More often and less specifically, mexicano was understood to mean any native speaker of Nahuatl, the widespread language of the Aztec empire. The term is further muddled by its association with the nation-state of Mexico (also named for the Mexica Tenochca), whose contemporary borders contain the ancient lands and cultures of central and northwestern Mesoamerica but also some lands to the east and south where speakers of various Mayan languages lived. Archaeologists, whose terminology I follow in this chapter, use “Mexican” to reference a culture area most strongly associated with Uto-Aztecan speakers in central Mexico, but also including the peoples of northern Mexico, Mixe-Zoque speakers from Oaxaca and Veracruz, and Otomanguean speakers in Oaxaca.5

Likewise, colonial-era Spaniards dubbed the area east of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec “Maya” based on stories they heard about the city of Mayapan, which dominated the Yucatan Peninsula in the fifteenth century.6 But the Maya area goes far beyond Yucatan, extending into much of Central America and including parts of the states of Chiapas, Tabasco, and Campeche in the modern nation-state of Mexico. What is Maya thus follows linguistic and cultural criteria rather than national boundaries. Linguists trace all Mayan languages to a single, Proto-Mayan idiom that began to branch out around 2000 B.C. In the lowlands of the Gulf coast, Yucatan, and El Petén, Guatemala, people spoke Yucatecan and Huastecan languages. In the highlands of modern Chiapas and Guatemala, a more complex situation evolved from four major language families. Today, over 30 Maya languages are still spoken in Chiapas and Guatemala, including Chontal, Tzeltal, Mam, Kanjobal, K’iche’, and Kaqchikel—a number that only hints at the linguistic complexity of earlier times. As in the Mexican west and north, many native languages in the Maya east and south have become extinct with the passage of time, the disappearance and migration of peoples, and the influence of Spanish.

Not everyone fits neatly into this scholarly Mexican-Maya schema. At Izapa along the modern border between Chiapas and Guatemala, artists in the third century B.C. carved some of the earliest depictions of important Maya deities. Yet the Izapans likely spoke a Mixe-Zoquean rather than a Maya language.7 Half a millennium later, Maya lords at Tikal claimed kinship with the kings of the central Mexican city of Teotihuacan. In Teotihuacan, meanwhile, the predecessor of the famous feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl was depicted in Maya style in the Tetitla murals, and central Mexican Nahua lore in the sixteenth century held that Quetzalcoatl came from the eastern direction of the Maya.8 The Pipil of modern Guatemala and El Salvador are not Maya, but descend from Nahuatl speakers who, archaeologists believe, migrated to Central America in waves from central Mexico and/or the Gulf coast in the early centuries of the first millennium A.D. And in the Spanish colonial period, the Mexicanos of Guatemala themselves confounded the strict categories of west/north and east/south, Mexican and Maya.

It is perhaps best, then, not to draw too harsh a dichotomy between Mexican and Maya, but to think instead in terms of Mexican-Maya relationships over time. From a Mesoamerican perspective, the invasion of highland Maya territory in 1524 marked a continuation as much as a break with ancient history, not necessarily in the dominance of Mexican over Maya but in a persistent pattern of connections across the Isthmus of

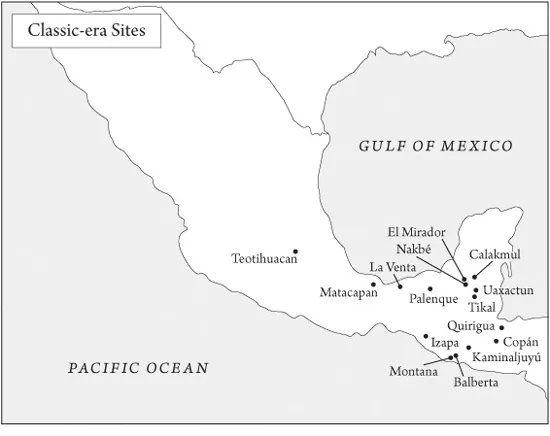

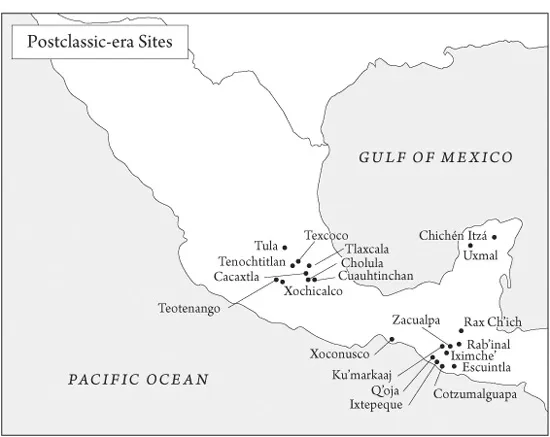

MAP 1. Classic and Postclassic Mesoamerica

Tehuantepec. Two epochs of ancient Mesoamerican history in particular bear on the later, sixteenth-century invasion of Maya lands. First is a brief period in the fourth and fifth centuries A.D., when the central Mexican city-state of Teotihuacan appears to have influenced or even violently interfered in Maya politics. Second is the much longer period to which the Guatemalan K’iche’ Popol Wuj refers, from the twelfth century to the arrival of Christianity to Mesoamerica in the sixteenth, the time of Tollan Zuyuán.

TEOTIHUACAN AND THE MAYA

The first hint in the archaeological record of significant Mexican influence in Maya areas, after many centuries of seemingly equal exchange between cities and peoples of the two regions, comes with the rise in central Mexico of Teotihuacan. For nearly 800 years, Teotihuacan was one of the largest and most enduring cities anywhere in the ancient world. It emerged as a major settlement in the Basin of Mexico rather abruptly around 150 B.C., and by the first century A.D. had absorbed most of the Basin’s local population. At its height, Teotihuacan covered some 20 square kilometers and provided residence to as many as 200,000 people. Its enormous Sun Pyramid was constructed around the same time that the city’s population began to boom, around 100 A.D. Some 20 other pyramid complexes followed, many of them connected to the north-south Avenue of the Dead that culminated in the Ciudadela, a rectangular complex built by the third century A.D. This complex includes the famous Feathered Serpent Pyramid, one of the city’s last monumental constructions built in the talud-tablero style often hailed as a hallmark of Teotihuacano architecture.9 The Feathered Serpent Pyramid also marks one of the earliest expressions of the famous Quetzalcoatl cult, iconographically linking royal authority and fertility with warfare and the celestial cycles of Venus.

Teotihuacan subsequently dominated the Basin of Mexico for some 500 years. Areas north and east of the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Memories of Conquest

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations, Maps, and Table

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Terminology

- Introduction

- 1 Indigenous Invasions

- 2 Templates of Conquest

- 3 Indian Conquistadors

- 4 The Primacy of Place

- 5 Creating Memories

- 6 Particularly Ladinos

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index