- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Conversations with the High Priest of Coosa

About this book

“This book begins where the reach of archaeology and history ends,” writes Charles Hudson. Grounded in careful research, his extraordinary work imaginatively brings to life the sixteenth-century world of the Coosa, a native people whose territory stretched across the Southeast, encompassing much of present-day Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama.

Cast as a series of conversations between Domingo de la Anunciación, a real-life Spanish priest who traveled to the Coosa chiefdom around 1559, and the Raven, a fictional tribal elder, Conversations with the High Priest of Coosa attempts to reconstruct the worldview of the Indians of the late prehistoric Southeast. Mediating the exchange between the two men is Teresa, a character modeled on a Coosa woman captured some twenty years earlier by the Hernando de Soto expedition and taken to Mexico, where she learned Spanish and became a Christian convert.

Through story and legend, the Raven teaches Anunciación about the rituals, traditions, and culture of the Coosa. He tells of how the Coosa world came to be and recounts tales of the birds and animals — real and mythical — that share that world. From these engaging conversations emerges a fascinating glimpse inside the Coosa belief system and an enhanced understanding of the native people who inhabited the ancient South.

Cast as a series of conversations between Domingo de la Anunciación, a real-life Spanish priest who traveled to the Coosa chiefdom around 1559, and the Raven, a fictional tribal elder, Conversations with the High Priest of Coosa attempts to reconstruct the worldview of the Indians of the late prehistoric Southeast. Mediating the exchange between the two men is Teresa, a character modeled on a Coosa woman captured some twenty years earlier by the Hernando de Soto expedition and taken to Mexico, where she learned Spanish and became a Christian convert.

Through story and legend, the Raven teaches Anunciación about the rituals, traditions, and culture of the Coosa. He tells of how the Coosa world came to be and recounts tales of the birds and animals — real and mythical — that share that world. From these engaging conversations emerges a fascinating glimpse inside the Coosa belief system and an enhanced understanding of the native people who inhabited the ancient South.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conversations with the High Priest of Coosa by Charles M. Hudson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1: The Coming of the Nokfilaki

The Raven would only converse with us at night. During the day, he said, children are always peering through the cracks in his walls, listening for what might pass between himself and his visitors. Women, too, are bad about prying into the affairs of men. Later I learned that Coosas are suspicious of anything that moves about in the darkness, whether animal or human, and since the last thing Coosas want is for suspicion to fall upon them, they do not travel about much at night, and that is the best time for privacy.

His house lay on the side of the plaza nearest the mound and the chief’s residence. As we stooped and entered the low doorway, stepping down to the sunken floor, we saw the old man sitting on a bed built against the opposite wall. It took some time for our eyes to adjust to the light from the tiny fire in the hearth in the center of the earth floor. The pyramidal ceiling of the house was supported by four stout posts, each set midway between the corners and the center of the floor. Beds were built around the walls at a height convenient for sitting. Small clay-plastered partitions built at the ends of the beds provided a little privacy. Closely woven split-cane mats lined the walls. The entire surface of the pyramidal ceiling, from where the central support posts joined the roof beams up to the apex, was plastered with clay mixed with grass for insulation and also to protect the roof from sparks that might drift up in smoke. The house smelled of the smoke of countless fires, strange foods, and dressed deerskins, and of the dried herbs hung from the roof beams and around the walls.

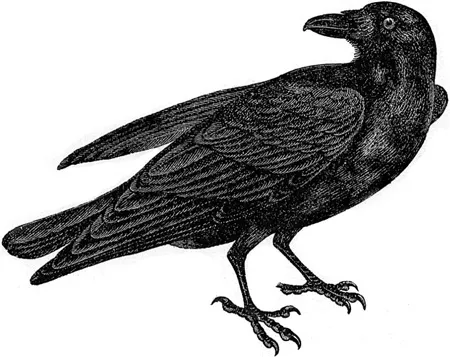

The Raven arose and stirred the fire, collecting coals and unburnt pieces of wood into the center of the shallow clay hearth in the center of the floor, and after a moment the fire began to brighten the room. Teresa and I were startled by a coarse pruk, pruk from a dark corner of the room. I could not see what made the sound. But then as the fire blazed up, I saw that it was a raven the old man had tamed and was keeping as a pet. It looked like one of the crows that raid Coosa cornfields, but ravens are nearly twice the size of crows; they make a different sound, and normally they stay up in the mountains, away from Coosa villages and fields.

Raven

As the old man showed us where we were to sit—I on the bed beside him and Teresa on a stout basket beside one of the support posts—he pointed to the bird and said: “His name is Pruk.” When Teresa translated the Raven’s words, she pronounced the bird’s name as he had spoken it, which was very close to the sound made by the bird himself.

After Teresa and I seated ourselves, the Raven began talking to us in a deliberate way, choosing his words carefully and speaking them in measured sentences. As Teresa translated, I wrote as rapidly as I could.

“What a time of suffering, disorder, and confusion we Coosas have had since you people first came to our land. No Coosa will forget that spring, one short lifetime ago, when we first heard from a man of Ocute that a band of strange men were traveling about. They were so peculiar they at first seemed not to be men at all—but they were men, and they bled when they were cut. Though they were not numerous, they were as confident as a falcon among doves. They had bested the Apalachees, and they walked through Ocute unopposed.

“The man of Ocute said that these people possessed wonderful weapons, unbelievable weapons—incredibly long knives. These knives were sharper than a sliver of hard cane or a splinter of fat-lighter pine. And most astonishing of all, these long weapons could not be broken. The man of Ocute said that these people came from the sea, and that their skin, where the sun did not strike it, was as white as sea foam. That is why we call them Nokfilaki, people of the ocean foam.

“Upon our first hearing of these strangers, some Coosas said that we need not be alarmed; we had only to bide our time. They said that soon the Nokfilaki would be among the wolves of Cofitachequi. The woman chief of Cofitachequi would kill them and drink their very blood. But before long we heard that the Nokfilaki had walked through Cofitachequi as easily as one walks through a morning mist. And worse, they had taken hostage a woman of the female chief’s clan.

“Then word came from a runner from the Chiaha, our allies up the valley to the north. The Nokfilaki had come to that land, and now they were on the move again, heading toward Coosa. They were enslaving people in the towns through which they passed—the young boys to work for them and the women to use as they pleased. They had wantonly destroyed some cornfields at Chiaha, and they seemed to be growing more belligerent and dangerous with every passing day.

“Many people of Coosa were now frightened. Others, and most especially our young men, clamored to kill the Nokfilaki. They wished to cut their bodies into pieces and hang them in trees for the birds to eat. Others said it would be better to capture the Nokfilaki and put them to work at menial tasks, like gathering firewood and carrying water.

“But the Sun Chief of Coosa was calm. No Coosas had seen these intruders; no one had seen how they waged war; no one had seen one of their long knives that could not be broken; no one had seen the huge beasts on which they were said to sit and be carried about in the land.

“The Sun Chief called a council of chiefs from all parts of Coosa. The chiefs assembled and quickly agreed that it would be better if they all combined their forces and acted together to resist the Nokfilaki. But it was the Sun Chief who first suggested that it would be better still if they could unite with their old enemy to the south—Chief Tascaluza—and thus make themselves an even more formidable force. Many Coosa warriors, who had bitter scores to settle with Tascaluza, would not hear of it. The Sun Chief answered them in this way: How will those of you who are killed by the Nokfilaki take vengeance on the people of Tascaluza? In the end, the assembled chiefs reached a consensus, and the irate warriors fell silent. Runners were sent to Tascaluza, and to the surprise of some, the word quickly came back that Chief Tascaluza would cooperate.

“The Nokfilaki came to Coosa, and as was our custom when powerful chiefs meet, we carried the Sun Chief out on a litter to meet with the chief of the Nokfilaki. We made a great show, with the Sun Chief’s retainers singing and playing on flutes, but the Nokfilaki could not hide their contempt for us, nor did they much try. They were far more terrible than we had feared. Not only did they possess miraculous weapons, but they wore on their bodies clothing so hard no arrow could penetrate. They seemed to be like so many snapping turtles, evil in temper and secure against all weapons. And not only did they ride upon the backs of those great beasts we had never seen before, which jumped about, snorting and farting, but the Nokfilaki also had at their command large dogs, dressed in the same impenetrable clothing that they themselves wore, that would attack and kill anything or anybody. They were man-eaters on leashes.

“Their chief was Soto, a man whom some of the Nokfilaki feared and hated almost as much as we did. He was a dry man, humorless, and always searching the faces of his men for hints of insubordination. He demanded that the Sun Chief hand over slaves and women, and with this the people of Coosa began to flee into the woods to find refuge. But the Nokfilaki sallied out and rounded up many of them, doing injury to some. Soto took hostage the Sun Chief, some women—including Teresa and the chief’s sister—and some of the chief’s principal men, and he said that he would throw them to the dogs to be killed and eaten if any of us attempted to interfere or resist.

“We could not understand what Soto wanted. Did he wish to be a paramount chief over Coosa? If so, why did he keep traveling from place to place? He showed us a yellow metal band he wore on one of his fingers, a metal that resembled our sacred metal—Thunder’s metal—but when we showed him some of our sacred metal, he was contemptuous. Soto said it was not the same as his. Ours is of a redder color and is softer. Soto kept demanding to know where was the greatest chief in the land. He wanted to find a chief greater than Sun Chief and a land more splendid than Coosa. He was as greedy as a cougar, who after killing a deer, will kill a second, far more than he can possibly eat, and he will lie between them to prevent any other from eating. We told him that a greater land lay ahead, and we gave him guides to lead him to the land of Tascaluza, where a trap was being laid for him.

“Chief Tascaluza launched his surprise attack on the Nokfilaki at Mabila, one of his subject towns. Days later, when we first learned what had happened there, we could not believe it. Even though we had surprise and a much larger number of fighting men on our side, the Nokfilaki drenched the ground with the blood of the warriors of Tascaluza and Coosa. Even though we set upon them the finest of our young men, trained from childhood in the warrior’s art, the Nokfilaki cut them down like dry cornstalks. Tascaluza’s chiefdom was ruined, bespoiled by the angry Nokfilaki, and Coosa suffered grievous losses. The life we knew before the Nokfilaki was altered on that day. The world is different now.

“When the Nokfilaki departed from Coosa, two of their number remained behind. One was Robles, who, just as they were about to leave, was kicked by one of the beasts on which they rode and suffered a terrible break in his leg. The Nokfilaki were unwilling to carry him through the long time of healing that lay ahead, and so they left him in Coosa. For many weeks he could not walk. Eventually his leg healed, but the broken leg was shorter than the other, and he walked with a limp. Robles was no good for war, but he would work at whatever needed to be done, and he was a cheerful man.

“Robles had not been born in the land of the Nokfilaki. He was born in a village, among farmers and hunters like ourselves, and he had been captured when he was a young boy and taken as a slave to the land of the Nokfilaki. His hair was as tightly curled as grape tendrils, and his skin was very dark. The children of Coosa liked this man very much, and they called him Burnt-by-the-Sun. He began learning our language quickly, and as he did he also learned our customs. He said that they were not so different from the customs of the village where he was born.

“Feryada, the second Nokfila to remain with us, did so against Chief Soto’s wishes. When the Nokfilaki departed from Coosa, Feryada lagged behind the others until he had fallen out of sight, and then he returned to Coosa. A day or two later, Indian runners came from Ulibahali saying that Chief Soto was angry at Feryada for trying to stay behind and that he must return to the Nokfilaki at once. He was assured that Chief Soto would forgive him if he would come back. But Feryada laughed at this, indicating by signs that Soto would throw him to the dogs. He remained here, and he had some very hard things to say about Soto and the Nokfilaki. Moreover, in time I realized that though Feryada seemed at first to be a Christian like the other Nokfilaki, he was in truth not a Christian. When the runner came from Soto to Coosa, Feryada drew a Christian cross in the dirt, spat upon it, and scuffed it with his feet. He indicated by signs that his god was not Christ, but a spirit called Allah.

“Feryada, however, was never content in Coosa. Later he wished that he were back in his own homeland. He even wished that he were back with the Nokfilaki. He learned our language only slowly, and he was not as interested in Coosa ways as Robles was.

“I had many talks with Robles and Feryada. Not even Robles learned the language of Coosa perfectly, but in time we understood each other well enough. The questions I asked about the land from which the Nokfilaki had come often exasperated them. They said that I asked them the meaning of things that any child should know. Their saying this amused me because they asked the same childish questions of me.

“It was Robles who first told me that the Nokfilaki can speak by making marks on thin white cloth [he meant paper], which they can send by a runner to another Nokfila, who can then look at the marks and speak the same words of the man who made the marks. And what is even more astonishing, a Nokfila can look at these marks four lifetimes later, and he can repeat the words exactly. With such marks on thin white cloth, as you yourself are making now, beloved knowledge can be kept forever.

“We Coosas only possess the knowledge that can be held in memory. Only a few of us are able to learn it well. And yet we try to increase our knowledge. That is why we were willing to give food and shelter to Robles and Feryada for so many years, forgiving them their blunders as they learned to behave and act as true men. We wished to learn from them, though much of what they said was so extraordinary we doubted that it was true.

“They told us that in the land of the Nokfilaki, people live in vast villages, and they are as numerous as ants. They are so numerous, some of them only grind grain into meal; others only weave cloth; others only make weapons; others only build houses—and nothing else. How could a man not know the ways of animals and how to hunt them? How could a man not know how to grow corn? Or how to build a house? We could not believe such stories.”

The Raven stopped his talk at this point, saying he had told me enough for one night. He took little comfort when I tried to explain that what Robles and Feryada had told him was true. The man who makes meal is a miller; the one who makes cloth is a weaver; the one who makes weapons is a blacksmith; and the one who builds houses is a carpenter. The Raven said that if this were true, it was a pitiful way for men to live. They would only be half-men, he said.

He said that the next time we conversed, he would tell me some stories. We would start in shallow water, as he put it. These first stories would be some that are known to every Coosa, man or woman, adult or child. Later we would go into deeper water.

After I returned to my ramada for the night, I sat by the fire reflecting on what the Raven had said. What he said about Hernando de Soto agrees with what the people of Nanipacana told us when we moved there from the port of Ochuse, the place where our governor Don Tristán de Luna landed and we unloaded our ships. The people of Nanipacana said that theirs had formerly been a great province, but they had been devastated by an army of people like ourselves who had been there earlier. It was plain to see that many houses in Nanipacana were vacant, ruined. Clearly the people of Nanipacana had been party to the conspiracy of Tascaluza.

My final thoughts on this eventful day were on Robles and Feryada. How would it have been for these two to live out their lives cut off from Christian brotherhood? Did the struggles of the Coosas become their struggles? Or were they only scorned and despised by the pagans, made strangers to human kindness for the rest of their days?

Chapter 2: The Contest between the Four-footeds and the Flyers

The next evening Teresa and I returned to the Raven’s house. Our commander, Mateo del Sauz, had forbidden Christians from entering the Coosa town after sundown, but he approved an exception in my case when I explained the purpose of my nightly visits. Fully expecting to breathe the corrupting air of the Devil’s own philosophy, Teresa and I prayed for God’s mercy before setting out on our visit.

As would be his habit, the old man greeted us and stirred the coals of his fire. His great black bird hopped down from his perch and strode over to the old man, looking up at his master with a cocked eye. The old man threw down a handful of boiled hominy, and the bird ate his fill and flew back to his perch, where he ruffled and preened his feathers.

“He begs for food,” the old man said. “And when his begging fails, he steals it. I think he is happier as a thief than as a beggar.”

When this spectacle was over, the old man directed us to take the seats we had taken before, and then he sat down on his bed. His practice was to either lean back against the wall or sit forward, resting his chin in his cupped hands. After a time of silence, he would begin to talk, and as he talked the fire gradually died down. I have recorded here exactly what the old man said as nearly as I could understand it, without regard to its merit in the eyes and ears of God, for which I beseech God’s understanding and forgiveness. My only intention is to put into the hands of the friars who come after me a tool by which they might lead these savages out of their benighted condition into the light and love of our Savior Jesus Christ.

After the customary time of silence, the Rav...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Conversations with the High Priest of Coosa

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- Acknowledgments

- A Letter

- Chapter 1: The Coming of the Nokfilaki

- Chapter 2: The Contest between the Four-footeds and the Flyers

- Chapter 3: More Animal Stories

- Chapter 4: Rabbit

- Chapter 5: Master of Breath and the Great Ones

- Chapter 6: Sun, Corn Woman, Lucky Hunter, and the Twosome

- Chapter 7: Horned Serpent, the Clans, and the Origin of Bears

- Chapter 8: The Vengeance of Animals, the Friendship of Plants, and the Anger of the Sun

- Chapter 9: Divination, Sorcery, and Witches

- Chapter 10: Sun Chief and Sun Woman

- Chapter 11: Tastanáke and the Ball Game

- Chapter 12: Everyday Life Is Their Book

- Chapter 13: Posketa

- Chapter 14: The Last Conversation

- A Note on the Spelling of Creek Words

- Sources

- Illustration Credits

- Index