eBook - ePub

Color and Character

West Charlotte High and the American Struggle over Educational Equality

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Color and Character

West Charlotte High and the American Struggle over Educational Equality

About this book

At a time when race and inequality dominate national debates, the story of West Charlotte High School illuminates the possibilities and challenges of using racial and economic desegregation to foster educational equality. West Charlotte opened in 1938 as a segregated school that embodied the aspirations of the growing African American population of Charlotte, North Carolina. In the 1970s, when Charlotte began court-ordered busing, black and white families made West Charlotte the celebrated flagship of the most integrated major school system in the nation. But as the twentieth century neared its close and a new court order eliminated race-based busing, Charlotte schools resegregated along lines of class as well as race. West Charlotte became the city’s poorest, lowest-performing high school—a striking reminder of the people and places that Charlotte’s rapid growth had left behind. While dedicated teachers continue to educate children, the school’s challenges underscore the painful consequences of resegregation.

Drawing on nearly two decades of interviews with students, educators, and alumni, Pamela Grundy uses the history of a community’s beloved school to tell a broader American story of education, community, democracy, and race—all while raising questions about present-day strategies for school reform.

Drawing on nearly two decades of interviews with students, educators, and alumni, Pamela Grundy uses the history of a community’s beloved school to tell a broader American story of education, community, democracy, and race—all while raising questions about present-day strategies for school reform.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Color and Character by Pamela Grundy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Educational Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

AN AFRICAN AMERICAN SCHOOL

On the morning of September 6, 1938, several hundred nervous but excited African American teenagers set off for the first day of classes at the newly built West Charlotte High School. Scatterings of students grew into clusters as they made their way past the neat rows of bungalows and cottages that filled the streets of Charlotte’s west side neighborhoods, while adults watched carefully from windows and front porches. Their paths converged at Beatties Ford Road, the two-lane thoroughfare that ran through the west side and out into the country. The imposing new building awaited them—a three-story, red-brick structure that held twelve teachers, sixteen classrooms and a library. Ten wide, concrete steps led to a set of double doors that opened onto the future.1

West Charlotte High School would spend its first three decades as an African American school, serving the children who lived in the west side’s African American neighborhoods. From the day it opened its doors, the school and its staff became an integral part of west side life, anchored in the surrounding community while also serving as a bridge to a wider world. In an era marked by the uncertainties of war, a changing economy, and an expanding civil rights movement, West Charlotte’s staff worked steadily at the challenging task of preparing adolescents to play multiple roles in their community and to navigate the shifting currents of the society around them.

West Charlotte opened in an auspicious time and place. The students who climbed the school’s front steps came from a community on the move, in which ambitious migrants were fashioning vibrant cultural and economic institutions. Charlotte’s population had nearly doubled in the prosperous 1920s, and continued to grow at a steady pace during the Depression. Earlier in the century, most of the city’s African Americans had settled in the heart of town, many of them in the all-black Second Ward neighborhood called Brooklyn. By the 1920s, however, the city’s burgeoning population began to push beyond its original four wards. Black families began to set their sights on the city’s west side, on a network of neighborhoods anchored by the elegant brick buildings on the campus of Johnson C. Smith University, a prestigious Presbyterian school founded in 1867 to educate newly freed African Americans.2

Charlotte’s pattern of racial and class arrangements had solidified early in the twentieth century. Throughout the nineteenth century, when social distinctions were maintained by a rigid code of hierarchical deference, Charlotte’s residents had clustered on a grid of center-city streets—black next to white, rich next to poor. But that arrangement had proved short-lived. In the heady decades that followed the end of slavery, Charlotte’s African Americans established schools, built successful businesses, and plunged into politics. In the 1890s, North Carolina’s black voters joined with rural whites to seize control of state politics. Faced with this challenge to their economic and political power, wealthy whites launched a violent white supremacy campaign that broke up the black-white Fusion coalition, stripped African Americans of their hard-won right to vote, and began to craft the elaborate legal and cultural structures of Jim Crow segregation. They then withdrew to suburban enclaves in the southern part of town, most notably the vaunted Myers Park, where curving streets ran past towering trees and large homes occupied well-landscaped lots. A combination of housing prices, restrictive covenants, and unspoken agreements relegated working-class whites to the company-owned housing that clustered around the city’s textile mills, or to inexpensive developments nearby. African Americans were steered west.3

West Charlotte’s first building, completed in 1938. The Lion, 1963. Courtesy of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room.

The African American west side began at the Johnson C. Smith campus, where Trade Street turned into Beatties Ford Road. Around the upper edge of the campus stretched the community of Biddleville—so named because it dated from the days Smith had been known as Biddle University. A few blocks up Beatties Ford Road, at the intersection with Oaklawn Avenue, a cluster of shops and businesses adjoined the neat wooden bungalows of Washington Heights, built in the 1910s at the last stop on the city trolley line. To the east, Oaklawn Avenue ran down to Greenville, a nineteenth-century black settlement that was quickly filling with new homes. While white neighborhoods were increasingly divided by economic class, the limited space available to African Americans meant that they clustered closer together. The attractions of suburban life and the amenities of an expanding Johnson C. Smith drew some of Charlotte’s most prominent African Americans—doctors, teachers, ministers—out to the new neighborhoods. But most of the area’s residents were recent arrivals from rural areas in North and South Carolina, families who purchased or rented modest houses and apartments, and who found work in trades such as gardening, housekeeping, and construction.

Future city councilman Malachi Greene, whose family came to Charlotte from rural Chester County, South Carolina, noted that his father had a simple explanation for the move: “The prospects for Negroes were better in Charlotte.” Charlotte was first and foremost a business town, in which the practical demands of making money led residents to look to the future rather than the past. While Jim Crow segregation remained firmly in place, this business-focused outlook fueled an ongoing economic boom that expanded the number and quality of jobs available to African Americans, as well as opportunities for black-owned businesses that served an all-black clientele.

Like their urban counterparts around the state, Charlotte’s African Americans were also beginning to cautiously reenter the political arena, often led by residents who could operate from the relative safety of the city’s growing number of independent African American institutions. By the mid-1930s, more than 600 African Americans were registered to vote, and in 1937, three African Americans ran for city offices. Mary McCrorey, the wife of Johnson C. Smith president Henry McCrorey, conducted what the Charlotte Observer called “a lively contest” for the Charlotte Board of Education. Funeral home proprietor Zechariah Alexander and businessman A. E. Spears competed for city council seats.4

Charlotte was far from paradise for African Americans. Hours were long and often irregular, pay was low, and police brutality was common.5 Black residents, no matter how capable, faced the indignity of official segregation and strict limits on their opportunities. High school students were not spared these hardships. “We had young men and women who didn’t know where the next meal was coming from, or whether someone was going to come by and have them put the furniture out in the yard this month,” recalled Charles McCullough, a tall, lanky boy who would become a national high-jump champion and then return home to spend three decades coaching West Charlotte’s basketball team. McCullough, who was raised by his grandmother, knew these economic pressures well. “I had to work,” he said. “I was working at the bowling alley and I was caddying at the golf course. Later on, I had to cook for my brother, because my grandmother got sick. So I was doing all those things along with trying to play football, basketball, baseball, and what have you.”

Hard work, limited health care, and environmental hazards made sickness and death regular features of life. The Greenville community, for example, sat next to the Southern Asbestos plant, which made fire-resistant asbestos fabric. Thereasea Clark Elder, whose family had left South Carolina to settle in a three-room home on Hamilton Street, recalled that in the summers workers would open the plant windows, releasing a fine, white dust that settled on porches and crept through window screens. Children played in the piles of asbestos waste heaped around the plant. Two of Elder’s siblings died before they reached the age of three, and her lungs became scarred from asbestos exposure. “They were defeated long before they had a chance to enjoy life,” she wrote of her siblings, noting that the pain of losing them contributed to her decision to go to nursing school, and then spend decades caring for Mecklenburg County residents.6

Some members of the community sought refuge from hardship in drugs or drink, and children knew to steer clear of the “cafe” one Greenville woman ran inside her home. More often, however, community members cushioned difficulties by helping one another. Families shared food from their gardens, helped with neighbors’ home improvement projects, and exchanged plenty of advice. “Everyone cared about everyone,” Elder recalled. “Everybody was aware of everything in that community. If anyone was sick, the community cared for that whole family. They provided wood, coal, food, whatever.” If a family was quarantined with tuberculosis, neighbors left food on the porch. One night Elder’s sister, Mae Clark Orr, was ill with tonsillitis, and both parents had to go to work. Mae woke up in the middle of the night to find a neighbor sitting by her bed, using ice to keep her cool. “That’s how close we were,” she said.7

Deaths in the neighborhood hardly had to be announced. “Every church had their bell, and when that bell toned, you knew that whoever was very sick in that church had died, and you would know where to go to carry the food,” Elder explained. “You would know that would be Nazarene bell, or that would be Second Calvary’s bell or that would be Brandon, whatever church.” Community members often stayed with a bereaved family for weeks. “There was always somebody there to fill that void.”

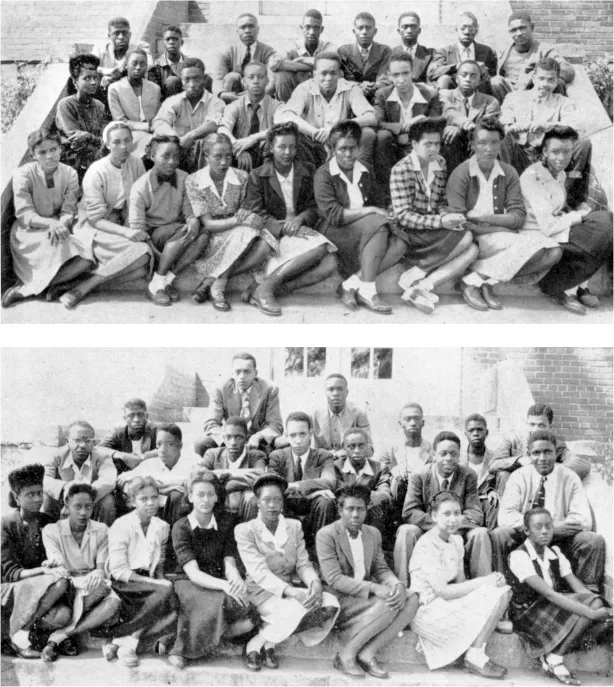

Newspaper staff (top) and journalism class. The Mirror, 1946. Courtesy of the West Charlotte High School National Alumni Association, Inc.

Community gatherings teemed with games, laughter, and food. Families and churches held picnics and fish fries where children and adults played games together. Young people gathered to listen to radios, strum guitars, and dance. When Charles McCullough was growing up in Fairview Homes, a public housing complex built on Oaklawn Avenue in 1940, adults organized games that ranged from horseshoes to bid whist. “These were people who knew if they didn’t have something for us to do, we were going to find something to do,” McCullough said. “We were going to be on top of those buildings . . . Or we were going to be up under the building, with the rats.” Greenville children spent their summers going to Bible school at first one church and then another, and swimming in the all-black swimming pool the city had built on the grounds of the old waterworks nearby. “We had plenty of activities to keep us busy, and it was all in the community,” Elder explained. “We didn’t have to go anywhere. We were entertained all day long.”

Children’s wanderings also brought them a wide range of experience. The constraints of segregation meant that most of Charlotte’s African American neighborhoods housed residents with many levels of income, education, and experience: the parents of students in one class at Biddleville Elementary School had education levels that ranged from third grade to Ph.D., and jobs that included janitor, elevator operator, undertaker, cook, hotel worker, railroad worker, painter, merchant, teacher, minister, farmer, and barber.8 Two of Greenville’s older residents had been born in slavery, and Mae Orr was endlessly fascinated by the stories they told about that dark era. Schoolteacher Jesse Bingham gave Sunday afternoon “tea lessons,” for which she got out her good china, served tea and cookies, and instructed neighborhood children in the niceties of pouring, setting tables, and genteel conversation. “She had a little whistle like a bird,” Orr recalled, and children converged on her house whenever they heard it.9

As west side children roamed their neighborhoods, played games, and socialized, they were rarely free from watching eyes. The social fabric their parents had created included a clear-cut set of expectations for young people, as well as a sense of shared responsibility for their behavior. It was an old-fashioned ethos, built around strict curfews, good manners, and respect for adults. If children strayed out of line—became unruly, disrespectful, or too loud—adults quickly stepped in. “They took care of us,” recalled Amanda Graham, who grew up on Fairmont Street in Biddleville. “If a parent would talk to a child, when you were doing something wrong, you had to stop doing whatever you were doing because that parent would tell your mother. That’s what happened in those days.”

Still, community members were as quick to praise as to scold, and children found themselves surrounded by warm encouragement. “Everybody took time for a child,” Elder explained. “You were nurtured in education, in religion and yourself. . . . I was always told that I was really important, that I was loved. ‘You keep that good work up.’ ‘I’m so proud of you.’ ‘You look so good today.’” At Fairview Elementary, Greenville residents packed the school to overflowing for school plays, recitations, and graduation ceremonies. “Everybody in the community went to everything that school put on,” Elder explained. “They would be hanging out of windows and everywhere, because the auditorium would be packed. . . . When the school and the church put on any program, they were there.”

Between 1923 and 1938, most of the west side’s high school students had to make their way downtown. Charlotte’s first black public high school—Second Ward High—was built in 1923, at a time when most of Charlotte’s African American residents lived in the center city. West side students walked or took the trolley to school, and students from rural areas often boarded with city families during the week.10 By the mid-1930s, however, population growth had led to massive crowding in schools across the city. In 1936, despite the challenges of the Depression, Mecklenburg County voters approved a million-dollar bond issue designed to relieve the overcrowding and, in the words of the Mecklenburg County Commissioners, “to give the city of Charlotte, and the rural sections of the county, school systems second to none in North Carolina.” The bond allocated approximately $100,000 for a new black high school, designed to educate students from seventh through twelfth grades.11

County commissioners initially sought to save money by planning to build the new high school on a crowded piece of city land that had once held the municipal waterworks. Charlotte’s African American leaders sprang immediately into action. Charlotte’s black citizens were as entrepreneurial as its white ones, and they knew that the new school’s location would have a significant effect on community development, as well as the value of the property surrounding it. They also understood the message the placement would convey. Two different community groups appeared before the commission to argue against the proposed site, which sat close to a railroad line, a machine shop, a foundry, and other industrial buildings. Such an unfavorable spot, contended longtime Johnson C. Smith professor E. A. Chisholm, would be “depressing to a high order of school work.”12

Nor did black leaders rely on the commissioners to pursue a change. Acting in a long tradition of African American educational self-help, they quickly located an alternate site: ten acres of farmland right on Beatties Ford Road, just a few blocks above the bustling Beatties Ford–Oaklawn intersection. The owner, prosperous African American barber Thad Tat...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures and Maps

- Introduction

- 1 An African American School

- 2 Civil Rights

- 3 Busing

- 4 Building an Integrated School

- 5 Pulling Apart

- 6 Resegregation

- 7 Separate and Unequal

- Final Thoughts: Past, Present, and Future

- Methods

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index