![]()

1 Cosmopolitan Domesticity, Imperial Accessories

Importing the American Dream

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, middle-class Americans commonly regarded household interiors as expressions of the women who inhabited them. As the author of a 1913 decorating manual put it, “We are sure to judge a woman in whose house we find ourselves for the first time, by her surroundings. We judge her temperament, her habits, her inclinations, by the interior of her home.”1 Motivated by that logic, American women with money to spend turned to their homes to define themselves.

One such woman, more typical in her taste than her extraordinary wealth, was Bertha Honoré Palmer. After the 1871 Chicago fire gutted the Palmer holdings, she and her millionaire husband invented themselves anew. They first rebuilt the Palmer House, a downtown hotel. In 1882 they started on a private residence, Palmer Castle, built on landfill fronting Lake Michigan. Contemporaries described the exterior as early English battlement style. Italian craftsmen laid the mosaic in the front hall, which set off the Gobelin tapestries on the wall. From there visitors could wander into the French drawing room, the Spanish music room, the English dining room, the Moorish ballroom, and the Flemish library. Upstairs, Bertha Palmer slept in a bedroom copied from a Cairo palace.2 The Castle, no longer standing, was a Gilded Age spectacle, but a curious one in light of the principle of self-revelation. Given the tendency to regard domestic interiors as an expression of their occupants, what explains Bertha Palmer’s efforts to stage the world in her household?

The story of the Palmers’ Lake Shore Drive mansion, rising from a former swamp, dripping with tapestries and heavy chandeliers, is in part a story about class—of the desire to display abundant wealth, the ultimate intent being to secure a hold at the top of the social pyramid. Acquiring the mellowed trappings of aristocracy was a means to compensate for the rawness of post–Civil War fortunes, to distance one’s dwelling from the vulgar commercialism that had enabled it to be built in the first place. (The Palmers’ fortune rested on retailing, real estate, and their hotel.) In choosing to shop abroad as well as in the United States, Palmer underscored her purchasing power, for interiors filled with costly foreign goods arranged against seemingly foreign backdrops signified wealth. Elegant European rooms won particular favor, but high-style Oriental rooms also could be extremely expensive. In an 1897 story by novelist, society writer, and domestic advice purveyor Constance Cary Harrison, the poor Virginian has only to see the “Oriental magnificence,” the “cushioned divans and filigree Moorish arches” of a New York apartment to fully comprehend its owner’s fortune.3

Even though Palmer was extraordinarily affluent, her tastes were not limited to the super rich. Countless middle-class women adorned their parlors with Turkish curtains, French styles of furniture, and knickknacks from around the globe. Though millions of dollars away from Palmer’s unattainable luxuries, these women nonetheless exhibited a relatively modest version of her far-reaching appetites. The housewife who draped a packing box with gaudy fabric in hopes of making an Oriental cosey corner was, as one decorating article pointed out, part of a trend that had, at its extreme, the “sumptuous and elegant affair found in the mansions of the wealthy.”4 No less significantly, this housewife was part of a design trend that encompassed Europe and that purportedly looked to the Near and Far East for its original inspiration.

Palmer and like-minded women undoubtedly wished to convey their economic standing through exhibiting imported objects and replicating distant styles, but their story is about more than just class. Through their households, these women strove to convey a cosmopolitan ethos—meaning a geographically expansive outlook that demonstrated a familiarity with the wider world. Their cosmopolitanism implied an appreciation of other peoples’ artistic productions. But theirs was neither a universalist nor an egalitarian cosmopolitanism. It was a cosmopolitanism that contributed to particularistic racial, class, and national identities. Not only did it emerge from U.S. commercial and political expansion, but it helped promote it. This was a cosmopolitanism that celebrated empire, on the part of both the United States and the European powers.5

Cosmopolitan domesticity, seemingly paradoxical by definition, was at odds with some core nineteenth-century ideas about households. Tract writers commonly presented the home as a haven from the outside world. As John F. W. Ware, author of an 1866 treatise on home life declared, “A home is an enclosure, a secret, separate place, a place shut in from, guarded against, the whole world outside.” Suburban homes in particular appeared as safe havens from the immigrants who swelled the cities and entered the most private sanctums of urban households in their capacities as servants. Yet urban homes also stood as bulwarks against the surging masses of city streets. Besides keeping the wider world out, homes were expected to keep middle-class women in. Ware, in full accord with many of his contemporaries, went on to pronounce the home “the peculiar sphere of woman. With the world at large she has little to do. Her influence begins, centres, and ends in her home.”6 Even those who found this vision of the home too restrictive, arguing instead that middle-class women should reach out from their homes to reform the wider society, joined with moralists such as Ware in presenting homes as fonts of racial, ethnic, local, and national identity. The shared assumption that homes were sheltered has obscured the extent to which they were firmly embedded in an international market economy. Nineteenth-century homes were loci not only of cultural production and reproduction but also of consumption, and in the period after the Civil War, much of this consumption had international dimensions.7

As the various theme rooms in Palmer’s castle suggest, cosmopolitan domesticity encompassed design choices as well as imported objects. In the late nineteenth century, U.S. decorators looked primarily to France and Britain for inspiration. Contemporaries regarded many of the rococo styles of the Victorian period as fundamentally French, and they snatched up empire and Louis XIV, XV, and XVI furniture, done in varying degrees of accuracy. The press paid considerable attention to French design, and imported French goods could be counted on to seem chic. “The French have the flavor and the delicate discrimination that, as a nation, young America still lacks,” wrote one Francophile in the Art Interchange.8 British styles had an equally loyal following, especially after Charles L. Eastlake published his Hints on Household Taste in 1868. By 1881 the book had come out in its sixth American edition and U.S. shops were stocked with furniture passed off as “Eastlake style.” Further testimony to Britain’s influence can be seen in decorating magazines’ glowing descriptions of English country homes.9

Along with French and British designs, other European styles found adherents. Among the sights found in U.S. houses were Italian, German, Dutch, Russian, Spanish, and Scandinavian theme rooms. The latter included Sara Bull’s Norwegian room, the centerpiece of her colonial house in Cambridge, Massachusetts. From the red and black corner fireplace to the bread baskets and milk jugs, the room evoked the atmosphere of her late husband’s Norwegian home.10

Although Europe exercised the greatest influence over U.S. decoration, not all theme rooms mimicked European dwellings. Decorators also drew on the Americas for inspiration, as seen in a “American Indian room” featuring curios from Mexico and Guatemala. “Many women of fashion have developed of late a fad for odd Oriental, South American, and Mexican belongings,” noted the Atlanta Constitution in 1896. “Today no woman with a charming home considers it complete without some bits of Mexican ornament.” This interest in seemingly traditional Central and South American objects intersected with the better-known enthusiasm for Native American rugs, pottery, and baskets.11 Whether from New Mexico or across the border, craft objects with Native American inflections appealed to Anglo purchasers.

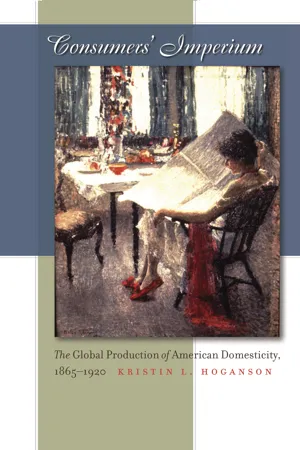

More common than Latin American themes and objects were Eastern ones, especially during the Orientalist craze that swept the nation from the 1870s to the turn of the century. Late nineteenth-century domestic Orientalism generally entailed fanciful productions passed off as Moorish, Turkish, Chinese, Japanese, or a combination thereof. This was not for everyone. Harriet Prescott Spofford made that clear in her 1877 book on home decoration, in which she said that Oriental designs would always seem fantastic in American homes and were best suited for “the very young and gay, and for those cosmopolitan people who are able to feel at home anywhere.”12 Despite—or what seems more likely, because of—its cosmopolitan associations, Orientalist design attracted a following among trendy homemakers. One enthusiast was Mme Theophile Prudhomme, a resident of New Orleans. She returned from a trip to the Far East entranced by what she had seen. So she created a Japanese room with screens, fans, mats, vases, and tea sets. It was so “rich in the colors and perfumes of the land of the ‘cherry blossom’” that a visiting reporter imagined herself as “indeed in Japan instead of a boudoir in far-off New Orleans.”13 A simpler interpretation of Japanese style can be seen in a five-room California bungalow profiled in the House Beautiful. This had sliding doors, walls painted in bamboo color, woven floor matting, and Japanese lanterns (ill. 1.1).14

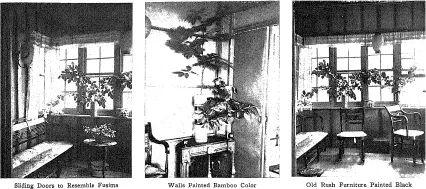

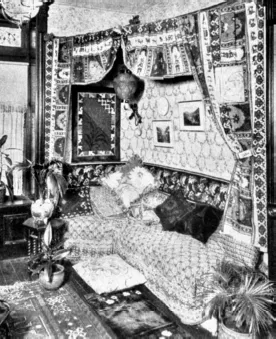

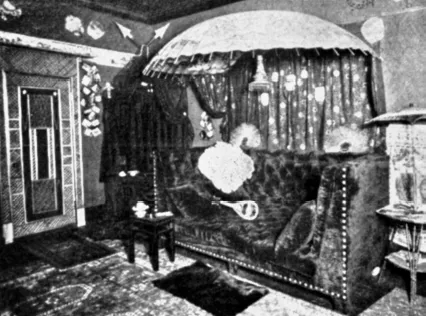

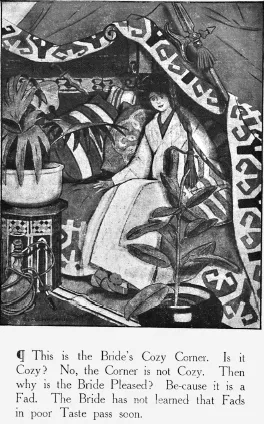

Decorators who lacked the wherewithal to turn an entire room into an Orientalist spectacle could still partake of the craze by producing an Orientalist “cosey corner.” These typically consisted of an upholstered divan, a profusion of cushions, a rug, a Turkish coffee table, a few decorative objects (such as screens, fans, lanterns, and pottery), and lush draperies to frame the entire ensemble. (Textiles played such an important role that a fabric company—sensing profit—published a booklet with instructions for making four different cosey corners.)15 Some cosey corners struck viewers as essentially Japanese or Chinese, but most looked primarily to the Middle East for inspiration. It is difficult to gauge the exact extent of their appeal, but they did spring up across the country. In 1897 a New York City couple constructed an Orientalist platform on one side of their apartment’s parlor. Another New York City apartment clustered tropical plants and Eastern textiles around a corner divan (ill. 1.2). A Chicago householder added a large parasol, spears, and fans to the basic arrangement (ill. 1.3). A Houston cosey corner had a pile of inviting pillows and an inlaid Turkish chair and table. A Denver cosey corner took up the bulk of a front hall. In the cold reaches of Montana, a teenager created a modest one in her bedroom. A woman heading to Argentina to work as a schoolteacher may have tried to produce one on shipboard, judging from the comments of an English passenger: “An American girl could contrive to make a desert look homelike, with a couple of Japanese fans.”16 Even the Good Housekeeping article that denounced cosey corners as a tasteless fad provides evidence of their popularity (ill. 1.4).17

1.1. Mary Rutherford Jay, “A Bungalow in Japanese Spirit,” House Beautiful 32 (Aug. 1912): 72. Courtesy of the Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur, Delaware.

The interest evinced by U.S. decorators in far parts of the globe differentiates the post–Civil War period from earlier eras. This is not to overlook the China trade and the enthusiasm for chinoiserie stretching back to the time when porcelain served as ballast for homeward-bound sailing ships or the scattered experimentation with other “Oriental” styles before the Civil War. But Chinese imports and chinoiserie of Western manufacture had been available to a comparatively narrow segment of the population, and other non-European design traditions failed to attract more than a modicum of interest.18 In the last decades of the nineteenth century, by contrast, a wider section of the American public had access to non-European imports, and taste makers touted products and styles from a broader expanse of the globe.

1.2. New York cosey corner, from William Martin Johnson, Inside of One Hundred Homes (1898), 44. Courtesy of the Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur, Delaware.

1.3. Chicago cosey corner, from William Martin Johnson, Inside of One Hundred Homes (1898), 54. Courtesy of the Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur, Delaware.

1.4. “This is the Bride’s Cozy Corner,” Good Housekeeping 41 (Oct. 1905): 385. Courtesy of the Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur, Delaware.

The popularity of Orientalist designs makes Bertha Palmer’s Moorish hall and bedroom seem somewhat less extraordinary. Novel though they may have appeared to the unsophisticated, they were fully in keeping with the design trends of her day. So was her mixing and matching of styles. Although some home furnishers favored a particular style, others turned their homes into virtual world tours. Like Palmer, these decorators crafted a series of nationally styled theme rooms.

Fashionable middle-class housewives (on whose shoulders fell the brunt of decorating responsibility) could struggle to produce a theme room or two, but only with great difficulty, and an entire ensemble of them lay far beyond grasp. But there was no need to despair. Just as a cosey corner could substitute for an Orientalist salon, a parlor stuffed with things from around the world could stand in for a series of national theme rooms. Late nineteenth-century design writings favorably profiled dwellings that mixed German tankards with French chairs and Persian embroideries; an Egyptian ceiling with Celtic ornaments and statues of Buddha; Moorish grillwork with a Louis XV chandelier, Swiss clocks, and a Florentine cabinet.19 “All nations are represented” enthused a Good Housekeeping article on a Philadelphia dining room.20 That such mixing was not limited to the mansions of the very wealthy can be seen in a profile of a small city apartment that combined Turkish brass, Japanese tables, a Chinese cabinet, carved gourds from Central America, a Mexican fan, a Breton vase, a Bohemian chalice, and posters from Paris and London. “Decorative art in this country is essentially eclectic, drawing from every available source,” claimed an 1886 essay.21

An eclectic mixture might be easier to pu...