eBook - ePub

Brown's Battleground

Students, Segregationists, and the Struggle for Justice in Prince Edward County, Virginia

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Brown's Battleground

Students, Segregationists, and the Struggle for Justice in Prince Edward County, Virginia

About this book

When the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, Prince Edward County, Virginia, home to one of the five cases combined by the Court under Brown, abolished its public school system rather than integrate.

Jill Titus situates the crisis in Prince Edward County within the seismic changes brought by Brown and Virginia’s decision to resist desegregation. While school districts across the South temporarily closed a building here or there to block a specific desegregation order, only in Prince Edward did local authorities abandon public education entirely — and with every intention of permanence. When the public schools finally reopened after five years of struggle — under direct order of the Supreme Court — county authorities employed every weapon in their arsenal to ensure that the newly reopened system remained segregated, impoverished, and academically substandard. Intertwining educational and children’s history with the history of the black freedom struggle, Titus draws on little-known archival sources and new interviews to reveal the ways that ordinary people, black and white, battled, and continue to battle, over the role of public education in the United States.

Jill Titus situates the crisis in Prince Edward County within the seismic changes brought by Brown and Virginia’s decision to resist desegregation. While school districts across the South temporarily closed a building here or there to block a specific desegregation order, only in Prince Edward did local authorities abandon public education entirely — and with every intention of permanence. When the public schools finally reopened after five years of struggle — under direct order of the Supreme Court — county authorities employed every weapon in their arsenal to ensure that the newly reopened system remained segregated, impoverished, and academically substandard. Intertwining educational and children’s history with the history of the black freedom struggle, Titus draws on little-known archival sources and new interviews to reveal the ways that ordinary people, black and white, battled, and continue to battle, over the role of public education in the United States.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Brown's Battleground by Jill Ogline Titus in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & History of Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

SEIZING THE OFFENSIVE

Reflecting on the racial code that defined his Virginia childhood, Rev. Leslie Francis Griffin, Prince Edward County’s “fighting preacher,” reminisced that “things were fine so long as we stayed in our place.” Virginia’s interpretation of Jim Crow was stifling to black aspirations but nonetheless distinct from the racial code that governed life in the Deep South. The Old Dominion, after all, had been the aristocratic capital of the Old South. White elites wholeheartedly supported segregation and disfranchisement but shunned vigilante violence as a threat to social stability. As esteemed political scientist V. O. Key wrote in 1949, “Politics in Virginia is reserved for those who can qualify as gentlemen. Rabble-rousing and Negro baiting capacities, which in Georgia or Mississippi would be a great political asset, simply mark a person as one not to the manor born.”1

The aristocratic Douglas Southall Freeman, editor of the Richmond News Leader and prize-winning biographer of Robert E. Lee, dubbed the state’s alternative approach “the Virginia Way.” Rooted in a notion of “separation by consent,” the Virginia Way allowed blacks a semblance of autonomy so long as they remained within the lines circumscribed by their white neighbors. White elites styled themselves the “patrons” and “guardians” of the state’s black population, appropriating the right to determine when and where uplift should be championed and when black aspirations should be squelched. More supportive of the establishment of segregated facilities for blacks than their neighbors further south, white Virginians generally accepted a certain level of black landownership and consumer buying power.2

Yet the unquestioned assumption of white superiority underlying this seeming moderation preserved a mentality of “privileges extended” rather than “rights demanded.” Casting themselves as benefactors, white leaders demanded that blacks approach them as supplicants grateful for the patronage of their “betters.” So long as blacks remained in their place, leaders strategically shunned the crassness of segregation by ordnance. They insisted that tradition, example, and social pressure could successfully guard racial lines.

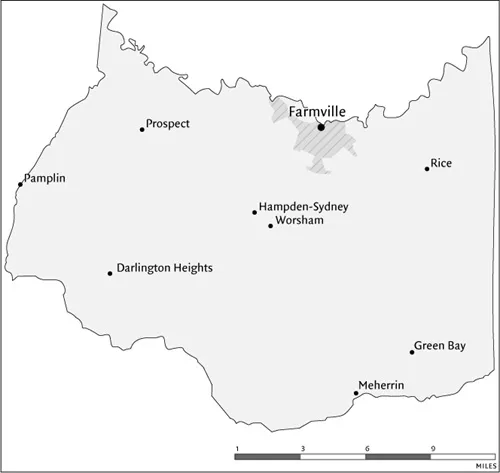

Virginia

Prince Edward County

Lawmakers pushed rabidly for disfranchisement but not separation. When vigilantism reared its head, authorities generally confronted it directly.

This model of race relations held sway through the early years of the twentieth century but lost ground in the 1920s as paternalism eroded in the face of urbanization and increasing black militancy. As African Americans flocked to the cities in search of economic opportunity, they altered traditional housing and employment patterns and challenged the constraints of familiarity and personal contact that policed race relations in the rural areas. The black press blossomed and the number of NAACP chapters in the state rose from two in 1915 to ninety-one by 1947. Newly empowered blacks turned to legal action and community organizing to signal their rejection of the paternalist bargain. Urban whites increasingly looked to municipal governments to enact laws protecting their whiteness from the tide of this rising assertiveness. As Freeman’s cohort of elites struggled to hold onto their increasingly dysfunctional model of voluntary separation, a new generation of leaders arose. Anxious to shore up the bastions of white supremacy against new threats, they blended the traditional anti-vigilante concern for law and order with a new determination to protect segregation by rendering it compulsory. Following the lead of extremists who redefined the debate in rigidly exclusionary terms, they swept into power on a platform of bureaucratizing and codifying segregation.3

Equally oligarchic and no more “popular” than its predecessor, this new generation of elites broadcast a new message that encapsulated the state’s changing mood. Freeman’s generation had argued that harmony depended upon each individual’s acceptance of his or her appropriate “place” in society, and that such acceptance could best be secured through informal means of control. Faced with shifting realities, the new generation concluded that acceptance must be coerced—not primarily through physical violence, which reeked of populism and threatened elite control—but rather through legal mechanisms. The pioneers of massive resistance—the political leaders of the 1950s—came of age in this climate. When confronted by Brown v. Board of Education thirty years later, they reached for the tools of control that took center stage in the 1920s: legislative mandate, bureaucratic procedure, and government action.

The “Virginia Way” protected and managed appearances at all costs. Stories of black discontent or civil rights activism rarely made their way into the newspapers, nor did accounts of police brutality against protesters in Danville. When the Freedom Riders passed through the state in 1961 in their courageous quest to test compliance with court orders mandating the desegregation of interstate transportation terminals, Virginians removed the “white” and “colored” signs from bus terminals. Waiting out the Riders’ presence, they then restored them, maintaining segregation for two more years. Sociologist Edward Harden Peeples Jr., a Virginia native and lifelong race-relations activist, described this approach as “a dignified way to be racist.” As he commented in a 2006 interview: “You can believe in white supremacy but you don’t have to hurt anybody to do it. You don’t have to restrain them with shackles. All you do is control their mind in such a way that they will appreciate the fact that what you do is good for them.”4

In the 1980s, Virginius Dabney, the esteemed editor of the Richmond Times-Dispatch, termed massive resistance an “aberration” in Virginia history, a momentary deviation from a consistent track record of good race relations. A racial moderate who advocated more equitable treatment for blacks throughout the 1940s and 1950s but who clung to the right to segregate, Dabney argued that the course of action adopted by the state in the 1950s “was untrue to its heritage.”5 But in truth, massive resistance was not an aberration. It was perfectly consistent with the major trends in state history. The commonwealth did maintain a reputation for harmonious race relations unparalleled throughout the South from Reconstruction through the mid-twentieth century. But commentators defined harmony as the general absence of vigilantism rather than the presence of equality. While Virginia’s leaders frowned upon extra-legal violence, they wholeheartedly embraced white supremacy. Whites maintained dominance through the exercise of governmental power to legislate, segregate, impoverish, imprison, and execute.

Early twentieth-century Virginia was essentially an oligarchy, controlled by as few as a thousand state and local officials, the majority of whom were cogs in Harry Flood Byrd’s legendary political machine. Governor from 1926 to 1930 and U.S. senator from 1933 to 1965, Byrd and his allies dominated Virginia politics well into the 1960s, concerning themselves primarily with maintaining a stable, low-wage labor force and low taxation rates, which they considered essential to stimulating the state economy. Deeply committed to avoiding debt, they embraced the concept of “pay as you go,” resulting in markedly low levels of public service that reinforced hierarchical distinctions.6

Virginia’s public schools struggled during the Byrd years. The O’Shea Commission, appointed to investigate the state’s public school system, found that in 1928 Virginia ranked nineteenth in the country and first among southern states in tangible wealth, but forty-fifth out of forty-eight in the percentage of wealth spent on education. Among the eleven southern states, Virginia, the most economically stable, stood second to last. The median spending on public schools was $18.47 per capita across the region, but Virginia’s expenditures averaged half this amount. Compulsory education laws went unenforced, and much of the population remained “lukewarm” on the topic of universal free education.7

Expenditures for African Americans were disproportionately meager. When the state adopted a compulsory school attendance law in 1922, state senators from the Southside (the heavily black area south of James River) objected on the grounds that such a requirement would force their white constituents to allocate funds for black education. They proposed instead a local option bill that allowed localities to exempt black students from the law. Although the legislature rejected this alternative, the O’Shea Commission duly noted that some local authorities chose not to enforce the law with respect to African Americans. The state accepted the commission’s findings with indifference, refusing to substantially increase its educational appropriations. According to Ed Peeples, “There’s always been a theme of opinion in Virginia by many of the elites that we didn’t need education. We ought to just get rid of public education: it’s insidious and it teaches egalitarianism and we’re not equal.”8

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education challenged this model of statesmanship. Though the General Assembly never abandoned its extreme fiscal conservatism or its aversion to providing public services, it rapidly began to flex its muscles as an “all-powerful government.” In the wake of Brown, the legislature undertook a program of coordinated activity that abrogated local option and centralized resistance as a state policy. Lawmakers who had recently considered boosting public services an intrusive government act voted to close schools and purge them from the rolls of state-supported institutions. Hostility to the idea of integrated public education broke down the traditional strictures on state government.

MASSIVE RESISTANCE

By the 1970s, massive resistance proved an enormous political miscalculation. Direct denials of federal authority provoked intervention. African Americans expertly identified the fissures in white unity in order to advance the civil rights agenda. Politicians who promised eternal resistance proved unable to deliver on their word. The crusade failed in all three of its central goals: holding the South to an undeviating adherence to the caste system, reestablishing a pre–Civil War concept of states’ rights, and insulating the region from the intrusion of new ideas and social practices. In hindsight, massive resistance appeared doomed from the beginning.9

But in 1954, obstructionists saw no reason why they should not prove victorious. The wave of resistance sweeping the South was unified, popular, and state supported. More than fifty segregationist groups sprang up in the years immediately following Brown, the majority of which were eventually absorbed into the Citizens’ Council movement.10 Spreading rapidly across the South to become the region’s most influential pressure group, the Councils brought in more members in 1954–55 than any other year. By 1957, more than one-half of southern states had repealed their constitutional requirements to maintain a school system. Violence and defiance became the norm as obstructionists took the reins across the South.11

Southerners in Congress placed the full weight of their influence behind undermining the decision. In March 1956, they introduced the “Declaration of Constitutional Principles,” better known as the Southern Manifesto. The architects of the Manifesto—Harry Byrd and South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond—encouraged local officials’ strategies of defiance, fished for support among states’ rights libertarians, and gave southern intransigence a congressional stamp of approval. Harry Byrd coined the phrase “massive resistance” in referring to the Manifesto as “part of the plan of massive resistance we’ve been working on.” As the 1950s wore on, Byrd’s home state pioneered massive resistance in practice as well as terminology. Virginia formulated strategies of legislative and legal obstructionism that soon became standard across the South, such as pupil placement boards, tuition grants, and harassing the NAACP.12

These strategies split white Virginians into three camps: segregationists, moderates, and progressives. Those in the tiny progressive minority called on the state to abandon white supremacy, protect black rights, and fully cooperate with the NAACP in its attempts to desegregate Virginia society. Segregationists, on the other hand, sought to preserve white supremacy at all costs, arguing that strict separation of the races was essential to the advancement of each. Segregationists refused to countenance even token integration, insisting that any relaxation in the state’s racial code would lead ultimately to interracial marriage and the subsequent collapse of white civilization. Moderates, regardless of their personal feelings about race, attempted to tack to a middle-of-the-road course. Eschewing outright defiance of federal authority, they championed open schools and slow, measured compliance with the Supreme Court decision in Brown.

Segregationists clothed their race-motivated defiance of the law in the language of states’ rights and interposition, arguing that the Supreme Court had overstepped its boundaries in Brown and the nation verged on descent into dictatorship by judiciary.13 Congressman Bill Tuck, a Byrd stalwart, feared school desegregation would destroy the Virginia Way. “We have not had any trouble between the races in Virginia of any consequence since the Civil War,” he insisted, erroneously. “A breaking out of trouble … would be tragic and would mar the good name and fame of Virginia.” Leading segregationists such as Tuck called upon the General Assembly to ensure that not a cent of state money would ever go toward maintaining a “racially mixed” public school system.14

Interposition—using state authority to shield residents from the dictates of the federal government—provided Virginia segregationists a language to use in courting support from political conservatives across the nation. By minimizing the racial content of their rhetoric and presenting their course of action as a campaign against judicial activism, leading Virginians actively sought to present themselves as natural allies of conservatives nationwide. The lead apostle of interposition, Richmond News Leader editor James Jackson Kilpatrick, repeatedly asked his audiences to lay social questions aside and “see clearly a constitutional problem that is not local, and not regional, but of grave concern to Americans everywhere.” This interest in wooing non-southerners strengthened the state’s historic hostility to the Ku Klux Klan and helped ensure that the newly formed White Citizens’ Councils would find few recruits in Virginia.15

Instead, hardcore segregationists banded together in a homegrown organization called the Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberties. Chartered in October 1954 upon the premise that integration meant “the death of our Anglo-Saxon civilization,” the membership of the Defenders peaked at approximately 12,000 at the end of 1956. Members tended to be fearful of any changes to the status quo. Most subscribed to a conservative/libertarian code of beliefs that included racial segregation, state sovereignty, and individual freedom from government controls. They associated the challenge to white supremacy with a Communist plot to topple American democracy and an attack upon parental rights, private enterprise, and the traditional family.16

In general, the Defenders carefully avoided overt forms of racial intimidation, thus differentiating themselves from the Citizens’ Councils. Individual members, however, frequently employed character assassination, threats to job security, and the silent treatment as weapons against dissenters. Adherents to the Defenders’ program denounced the weak Civil Rights Act of 1957 as an abomination “created for an evil purpose—the political and social enslavement of 50 million American citizens,” and termed its 1964 successor “pernicious.” When civil rights demonstrations swept the nation in 1963, they called upon law enforcement officials to handle “these so-called non-violent persons” in the same way they would handle armed criminals. Though their tactics, and perhaps to a certain extent their beliefs, differed from other white supremacist groups such as the Councils and the Ku Klux Klan, members of the Defenders nonetheless sought the s...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- BROWN’S BATTLEGROUND

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS & MAPS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION MOTON HIGH, 1951

- CHAPTER 1 SEIZING THE OFFENSIVE

- CHAPTER 2 WE SUFFERED OUR CHILDREN TO BE DESTROYED

- CHAPTER 3 FRIENDS IN THE STRUGGLE

- CHAPTER 4 THE GREATEST GIFT WE EVER SHALL RECEIVE

- CHAPTER 5 DIGGING UP SOME LIBERALS

- CHAPTER 6 THE LONG HOT SUMMER, 1963

- CHAPTER 7 WASHINGTON, D.C., MEETS FARMVILLE

- CHAPTER 8 THE LAW HAS SPOKEN

- CHAPTER 9 STANDING TOGETHER

- CHAPTER 10 MOTON HIGH, 1969

- CHAPTER 11 CARRYING ON

- CONCLUSION VICTORS OR VICTIMS?

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX