![]()

CHAPTER ONE

DISCRIMINATION AND DISSENT

NORFOLK UNDER THE OLD DOMINION, 1938–1954

IT CERTAINLY WAS UNUSUAL. On June 25, 1939, at St. John’s African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Norfolk, Virginia, over 1,200 African Americans signed a petition requesting that the city’s school board rehire chemistry teacher Aline Black, who had recently been dismissed from her position at nearby Booker T. Washington High School. Just prior to the St. John’s meeting, “a large number of Negro children, led by a Negro Boy Scout Drum and Bugle Corps, marched from the Dunbar School into the church, carrying banners.” Their procession route took them from the western edges of the mainly black Huntersville neighborhood through “the Harlem of the South,” Norfolk’s vibrant Church Street business district. Their banners and placards skillfully alluded to current events — like the rise of dictatorships in Europe — to stress the significance of the plight of Black, who had lost her annual contract with the school board when she challenged the district’s policy of separate and unequal salary scales for white and black faculty members. Accordingly, the march to St. John’s, the largest and oldest African American church in Norfolk, made for powerfully and intentionally corrosive street theater as the children walked past with their signs that stated, among other things: “ ‘Dictators — Hitler, Mussolini, Norfolk School Board,’ … ‘The Right of Petition Ought Not To Be Denied American Citizens,’ ‘Our School Board Has Vetoed the Bill of Rights,’ … ‘The School Board’s Method of Dealing With Colored Teachers is Un-American.’ ”1 Framing the school board’s racism as foreign and totalitarian made for good politics, while having over 100 children demonstrate was an absolute stroke of genius on the part of the local organizers: insurance salesman David Longley, dentist Dr. Samuel F. Coppage, attorney P. B. Young Jr., and railway mail clerk Jerry O. Gilliam.2 Their casting of children in the march either consciously or unconsciously mocked the prevailing white Virginian view of blacks as unwanted and perpetually immature wards who would never dare to criticize the white establishment that ran the state.

Whatever its dramatic intentions, this children’s procession was quite a spectacle, as collective demonstrations of African Americans protesting injustices were only too rare in Jim Crow Virginia, which had long prided itself on ostensibly harmonious and, in the judicious phrasing of historian J. Douglas Smith, “managed racial relations.” In return for fewer lynchings and hate crimes, Virginia’s blacks were supposed to be grateful and to show their gratitude by not challenging the separate and unequal status quo.3 That certainly extended to the sphere of public education, where teachers were paid differently because of race and, to a lesser degree, because of gender. This institutional inequality had long been resented, if accepted, by nearly all black teachers who were eager to eke out some kind of professional career within the confines of Jim Crow. That was the case in Norfolk until the NAACP encouraged the impeccably qualified Black, a twelve-year veteran of the school system and an Ivy League graduate, to petition, in October 1938, and, then, in March 1939, to file suit against the Norfolk School Board. Backed by her team of lawyers that featured Thurgood Marshall, Black’s defiant courage weakened the precepts of local paternalism that had always denied African American agency. Although she lost her case on June 1, 1939, just bringing it publicly emboldened and inspired others, if only temporarily and dramatically at St. John’s later in the month. On the other hand, the school board’s subsequent mistreatment of Black lessened black deference to white leadership. The school board not only released her without legitimate cause two weeks before the actual court decision, but then it had the audacity to charge her $4.01 for the school day that she had spent in Judge Allan Reeves Hanckel’s circuit court. This overreaction was obviously crass and displayed a seemingly un-Virginian kind of pettiness, which did worry the devotees of “managed racial relations” as much as it seemed to galvanize the crowd at St. John’s.4

Historians have closely analyzed the immediate causes and consequences of the Aline Black lawsuit and its even more famous follow-up, Alston v. School Board of the City of Norfolk (1940), but they have never connected the themes, individuals, institutions, and strategies featured in these familiar landmark events with similar ones found in such dramas as the school closures crisis and the advent of busing that would happen later in the century. The best secondary accounts of NAACP activity and twentieth-century African American life in Norfolk are those set during the Depression and World War II, and they end just before the Brown decision. Then, African American agency and sources are strangely either omitted or pushed to the margins in Norfolk’s transformation from prewar backwater to postwar “Sunrise City by the Sea.” This has led to unfortunate errors and gaping holes in the current historiography. Most significantly, J. Douglas Smith contends that lessening black deference and its obverse, growing white Negrophobia, had eroded the “managed racial relations” of elite paternalism in the Old Dominion to the point that it was no longer relevant by the 1950s. While no one would dispute that “the Virginia way” and its particular expressions in Norfolk changed dramatically between 1909 and 2009, this and subsequent chapters show the continued uses, transpositions, and reconstitutions of Virginian paternalism in Norfolk, particularly in the key sphere of public education, well past its alleged death. For instance, a major component of maintaining white supremacy was the interracial or biracial committee of notables, a frequent white resort to calm black anger or resentment that, in turn, would be refitted or rejected by black leaders for their own purposes from the 1940s onward. Indeed, while the St. John’s protest showed a rare degree of unity among local and national black leaders, division and diversity of opinions among local blacks about how best to achieve equal educational opportunities were the norms both before and well after that protest, providing periodic and, occasionally, key comfort to the defenders of the racial status quo. Furthermore, as Mark V. Tushnet has shown, a major component of preventing salary equalization from coming after the successful Alston case was the practice by school boards of what the NAACP’s 1941 pamphlet, Teachers’ Salaries in Black and White, called “intimidation, chicanery, and trickery of almost every form imaginable.”5 Finally, in providing a usable touchstone for much-needed analyses of later events, this chapter offers an urban geography of Norfolk under Jim Crow, building upon and tailoring the pioneering work of historian Earl Lewis and urban studies analyst Forrest White Jr. in order to comprehend the local desires for equalization and then for desegregation. This setting of the stage is necessary to understand the later periods of desegregation, integration, and resegregation that have been treated separately and unevenly, if at all, by scholars of Virginia history.

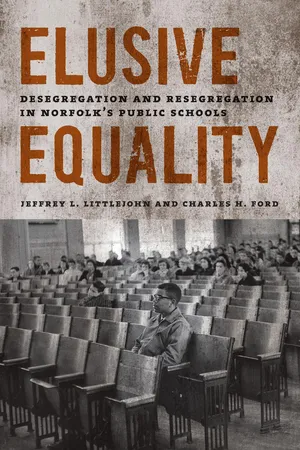

On June 25, 1939, local residents held a demonstration at St. John’s African Methodist Episcopal Church to protest the dismissal of teacher Aline Black. (Courtesy of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People)

TO TRACE THESE continuities first requires a closer look at the St. John’s rally and its immediate effects. While Norfolk’s self-presentation as the “All-American City” was still a generation away, its leaders did worry about damage control in the wake of the board’s decision to release Black. Both in its article on the mass protest and its editorial a day later, the Virginian-Pilot was clearly more concerned about what it deemed as the harmful effects of the Black case on the maintenance of a humanized and workable segregation than it was about achieving real salary equalization. For example, in its coverage of the event, it placed the reactions of two prominent local whites at the rally — the Reverend Gerald Evans Hopkins, of Le Kies Methodist Church, and W. D. Keene Jr., federal customs inspector and executive secretary of Norfolk’s own Interracial Commission — before the coverage of the petition or the speech by Walter E. White, the executive secretary of the NAACP. The attenuated nature of the support that these two white leaders offered in defense of the rally was even more revealing than its textual placement, however. As a resident of the streetcar suburb of Colonial Place, Keene insisted that he was there as an individual and not as a representative of the commission, which was to meet on this issue later in the week. The Reverend Hopkins was also a member of this body, but he apparently did not feel the need to make a disclaimer about representing it. Hopkins might have been more socially confident and aware than his cautious colleague; he lived in Ghent proper, one of the “best” addresses in the city, even if his church was across the Hague waterway in the working-class Atlantic City neighborhood. At any rate, Keene’s reticence was not entirely necessary, since the commission would soon vote to support Black, and its chair, Juvenile and Domestic Relations Court Judge Herbert G. Cochran, would petition the school board to reinstate her.6

For his part, the Reverend Hopkins endorsed the particulars of the petition, but he also told the black audience members that they should work to understand and forgive the errant school board. Hopkins stated, “Remember there are at least two sides to each question. In their minds these members of the school board, some of whom I know personally and admire, think they are doing the right thing.” In other words, according to Hopkins, the audience members and marchers at St. John’s were to forgive the board members in the same unconditional way that Christ had forgiven the sins of the members of the crowd. To do otherwise would have upset the “managed racial relations” that the interracial commissions of the 1920s and 1930s were supposed to ensure. Hopkins admitted that his sympathy for the goals of the petitioners was not shared by a majority of the white residents of Norfolk, but he predicted that his position would become much more commonplace with an increase in both the practice of Christianity and the “general educational level of our white people.”7

More reflective of mainstream white opinion on this matter was the editorial in the Ledger-Dispatch, the smaller, more conservative, and less fashionable white newspaper in the city. It vehemently denied that the school board “was venting something like spleen” and did not appreciate the board being portrayed as “a public enemy.” Still, the editorial was “uncertain” about the decision to release Black, but it suggested that she ought to have expected that move, given her “contumacious attitude.” A “contumacious attitude” was unacceptable for any employee, but it was certainly beyond the pale for a black woman in Norfolk who dared to challenge the system.8

Like Keene and Hopkins and unlike the Ledger-Dispatch, the famed editor of the Virginian-Pilot, Louis Jaffe, urged the board to reconsider its decision by “doing the right thing” and rehiring Black, if for the same concerns about racial harmony, not racial equality. Like Hopkins, Jaffe knew the board members personally, finding them to be “public-spirited individuals who are above the temptation of petty reprisal.” He blamed the state government for pressuring the school board in Norfolk to act as its “catspaw” in “the pay-parity controversy.” The board members were not to blame. Their unfortunate detour from reason, to Jaffe, nevertheless did “untold damage to the city’s interracial relations.” The decision to fire Aline Black had only stirred up trouble in the form of the “formidable” parley at St. John’s, which, gratefully to the editor, only witnessed “a few sharp and resentful words” and largely was free of “provocative or abusive polemics.”9

While firmly grounding their remarks in the tropes and images of American secular religion so beloved by Jaffe, the black speakers at St. John’s were not content with waiting either for white people to get educated or for them to do the right thing. With a new world war between the democracies and dictatorships about to erupt in Europe, P. B. Young Sr., the longtime editor of the city’s black weekly, the Journal and Guide, clearly defined the Black case as a fight between “Democracy” and “Autocracy.” In this same martial vein, Walter White referred to a different Jesus than did the Reverend Hopkins, preferring those present to chase the moneychangers out of the temple instead of instinctively turning the other cheek. Thurgood Marshall similarly reminded everyone to fight as well as to pray, joking that that was what blacks did in “civilized countries” such as his neighboring Maryland where, according to him, all teachers had tenure after three years of service. He boasted of a “war-chest” to carry on the appeals process as well as to assist the now-unemployed Black. To Marshall and every other African American speaker, including the Reverend Walter L. Hamilton of Shiloh Baptist Church, the best way to get rid of the rascals on the school board was to vote for a new city council, which would then appoint new members to the board who were more accountable to the city’s black citizens.10

This threat was much more credible by the late 1930s than at any other time since the Readjuster era of the early 1880s, as locally based white politicians such as Colgate W. Darden Jr. had to compete in contested federal elections for black votes. The federal courts had struck down Virginia’s white primary in 1929, opening the way for the semblance of biracial New Deal coalitions even in the Old Dominion.11 It is true that poll taxes and voter apathy had artificially depressed the numbers of eligible black voters in Norfolk, as a 1941 survey done by Luther Jackson, a professor of history at all-black Virginia State College in Petersburg, would conclude. Yet that same study and its ensuing campaign to get out the black vote would contribute to the long-term trend of more African American taxpayers and voters in the port city than ever before.12 While electoral victories seemed within reach for black leaders in Norfolk once again, however, clear-cut mandates for dismantling Jim Crow remained elusive, and both the local and national NAACP deduced that the best venue to seek equality under the law in the short term remained the courts, even if Aline Black had lost in the first round. They firmly believed that they would eventually win, even if it took many years.13

This confidence and corresponding, if temporary, unity was certainly on display at the national NAACP’s annual convention held in nearby Richmond a few days after the St. John’s protest in Norfolk. Roughly 5,000 delegates as well as the mayor of Richmond, J. Fulmer Bright, and the governor of Virginia, James C. Price, gathered at an “immense” auditorium, while thousands more listened outside to the convention’s celebrity speakers via a public address system. Mayor Bright even published a letter of welcome to the convention in the Richmond Afro-American, the capital’s black weekly. The leading white celebrity at the show, however, was none other than First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who was invited to speak and present opera singer Marian Anderson with the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal Award. This recognition was for Anderson’s ultimate public relations victory during the previous spring over the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), which had refused to allow her to perform at their hall because she was black. Roosevelt had resigned from the DAR in protest over Anderson’s mistreatment, and she had been instrumental in getting Anderson to sing at the Lincoln Memorial instead. While basking in that shared triumph, Roosevelt did go ever so carefully beyond just celebrating the resolution of the Anderson controversy. In remarks carried by both the Columbia Broadcasting and National Broadcasting companies’ radio networks, the First Lady elliptically referred to the necessity of “educational reform” for the “preservation of democracy,” a coded endorsement of the NAACP’s equalization efforts.14 In their speeches, Charles Houston, the NAACP’s chief counsel, and Walter White were far less circumspect than Eleanor Roosevelt had been. While Houston unequivocally endorsed the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Gaines v. Missouri, White, to “tumultuous applause,” beseeched Governor Price to “do his utmost to render justice” in reference to the Aline Black case.15

It had taken the NAACP many months to achieve that moment of local consensus and national awareness evident at both St. John’s and in Richmond, but that unity of purpose among local and national black leaders was fleeting and ultimately unsatisfying to both. While black teachers in Norfolk worked with the national NAACP to secure pay parity in local schools, the city’s most prominent African American leader, P. B. Young Sr., worked out a conciliatory deal of his own with the white power structure.

A native of small town North Carolina, Young had been in Norfolk since the Jamestown Exposition of 1907. By the 1930s, he and his family lived on Chapel Street between two black neighborhoods: Uptown and Huntersville. The Journal and Guide’s offices were located just a short walking distance away at 721 E. Olney Road, a convenient location near the Church Street business district. Working close to home, Young was never really interested in making big profits. He was concerned with wielding power and shaping opinion, however. Over his thirty-year career as a newspaperman and banking executive, Young had become very influential in explaining the actions of whites to blacks and vice versa. He was more than a big fish in a small pond, however, having achieved a degree of statewide and national prominence as a trustee of the Jeanes Rural School Fund as well as one of the best black colleges in the nation, Howard University in Washington, D.C. Such power in a segregated setting did not come without its price in integrity and consistency. Young was no “Uncle Tom,” but he could certainly and convincingly act in that role if he could win real, if piecemeal, concessions from whites. His definitive biographer, Henry Suggs, has aptly characterized Young as a “militant accommodationist,” and, true to form, in the pay-parity cases, he at first played the militant, only later to switch to the accommodationist role when it looked like the best possible settlement was near.16

Indeed, Young as “militant” was just as believable to contemporaries as was his trimming of news articles to please skittish white patrons and advertisers. As the Journal and Guide grew in circulation from 20,000 subscribers in 1933 to over 65,000 in 1944, his paper unequivocally backed the ...