![]()

Chapter 1

People Are Power

The Mass Uprising and the Maverick Coalition

In early 1938, nearly ten thousand mexicano workers walked off their jobs hand-shelling pecans in dismal warehouses scattered across the West Side of San Antonio. Organized block-by-block throughout the city’s sprawling, impoverished barrios, the general strike quickly took on a larger meaning. Activists and police authorities alike talked of “a mass uprising.” Union members and organizers clashed with police and filled the local jails for nearly two months. Strikers and the unemployed converged on City Hall, rallying for change. Soon the entire neighborhood was up in arms, fighting for better living conditions in addition to higher wages on the job. A “revolution” was taking place.

Against all odds, the mexicano workers won. Although the victory on the shop floor would prove fleeting, the larger impact of their movement could hardly be overstated. The following year, a maverick New Dealer would ride the wave of the insurgency to the mayor’s office, bringing the Mexican American pecan shellers into common cause with white labor activists, liberals, and the city’s first independent African American voting bloc. The rise of a newly militant faction on the all-black East Side would prove especially transformative, laying the foundation for a generation of civil rights struggles and multiracial collaborations across the city and state. More immediately, the loose coalition behind the mayor would weave demands for economic justice and calls for civil rights into a powerful mixture that would break the back of San Antonio’s political machine. Although the mass movement would eventually succumb to external pressures, it would first plant the seeds of a decades-long, broad-based struggle for democracy. Politics in Texas would never be the same.

George P. Lambert and the Reds in Dallas

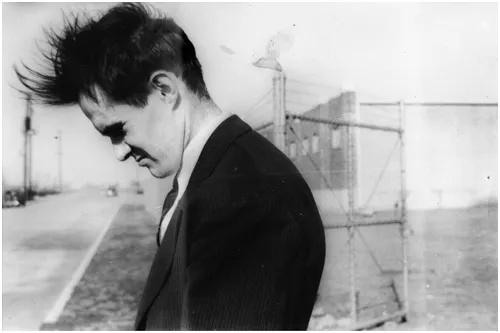

At the middle of the coalition in San Antonio stood George Lambert, a young idealist from the coalfields of West Virginia. A slender man with dark, combed-back hair, thick eyebrows, and an intense, piercing gaze, Lambert came to the Alamo City via Dallas after stops across the American South. He was born in 1913 in Bluefield, West Virginia, and became a socialist, pacifist, and trade unionist while working his way through the state’s flagship university in the early 1930s. A professor introduced him to the Young People’s Socialist League and the Student League for Industrial Democracy, both of which pushed him into the Socialist Party then led by Norman Thomas.

A young George Lambert, the student socialist turned union organizer and lifelong civil rights and political activist, outside near a factory in San Antonio in the late 1930s. Courtesy George & Latane Lambert Papers, Special Collections, The University of Texas at Arlington Library, Arlington, Texas, AR127-19-6.

Lambert gained vital hands-on knowledge in 1934, when he took a summer job at a nearby garment factory. He didn’t last long, getting fired along with several of his coworkers for contacting a union organizer. The union helped Lambert get a job in an area coal mine, where he joined the United Mine Workers (UMW) and remained for the rest of the summer. Still, he continued to learn on and off the job, soaking up the class struggle firsthand. One day on his free time, he visited a picket line of white women striking another garment factory in the area. Lambert watched in awe as the women dove into the muddy streets outside the building, laying their bodies on the line to block trucks from approaching the plant. Around the same time, Lambert began tagging along with a UMW staffer as the union tried to reorganize the coalfields of northern West Virginia. Talking to wizened old miners, he gained still more on-the-ground experience before heading back to Morgantown to return to school.

Lambert didn’t make it long in the stuffy confines of the university. More than ever, he believed in unionism, socialism, and peace among the world’s working people. When he refused to enroll in mandatory ROTC classes that fall, he was duly expelled.1 News of his defiance traveled, and the Quaker-affiliated Guilford College in North Carolina stepped in to offer the courageous pacifist a scholarship to continue his formal education. But even after he moved to the Tar Heel State and again enrolled in school in 1935, the labor movement and the Socialist Party continued to pull him away.

A disastrous industrywide strike had devastated North Carolina textile workers the previous year. Signs of violent clashes abounded. In Greensboro, the gates at Cone Mills were adorned with mounts for machine guns. A single organizer of the textile workers union was now responsible for the entire state, so he gladly assigned several cities to the eager young volunteer from West Virginia. Near Durham, Lambert later remembered, a group of “people obviously connected with the mill owners” pulled him and his collaborators off the train platform and threw them in jail overnight. Surviving arrest intrigued rather than rebuffed the young activist, who “got so interested in the labor movement” that he “lost interest in getting a college degree.”2

Lambert became more active than ever in the Socialist Party, an avocation that took him to Tennessee, Arkansas, and Georgia. Along the way, he gained his first, life-changing exposure to the struggle against Jim Crow. In 1936, the college dropout helped coordinate the gubernatorial campaign of Kate Bradford Stockton, one of a handful of Tennessee “mountain socialists” who helped launch the Highlander Folk School, a soon-to-be legendary training ground for labor and civil rights activists.3 While crisscrossing the state with various socialists, Lambert attended some of his first interracial meetings. On one occasion, H. L. Mitchell, the head of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU), brought him to a lively rally of African Americans on the courthouse steps of Earl, Arkansas. Gathering under the watchful eye of hostile deputy sheriffs known for arresting black dissidents and hiring them out as convict laborers, the ordinary tenant farmers, black and white, astounded Lambert with their courage. He was especially impressed by the black unionists that came to the rally despite risking being forced into “slave labor” for the cause. Around the same time, Lambert traveled to Memphis, where he worked with a local branch of the Workers Alliance of America, a group of the poor and unemployed that advocated for expanded relief from the New Deal and local agencies. He again saw the inside of a southern jail cell after being arrested for showing a film without a license at a Memphis STFU meeting.4

Lambert drifted on the Socialist Party circuit following Stockton’s defeat. Late in 1936, he went to Atlanta to support a group of autoworkers who had sat down at their machines and refused to work. One month before the months-long sit-in in Flint, Michigan, the Atlanta workers were offering a glimpse of the ultimate solution to the age-old problem of how to truly shut down a company. The North Carolina women had lain down in the streets, while the Atlanta men sat down on the job to prevent the hiring of scabs. Lambert was exhilarated by the fight, joining the picket soon after the men left the plant. He drove around town drumming up support for the workers from a bright red truck equipped with a billboard on the roof and a megaphone blaring old labor songs such as the “Internationale.”

While in Atlanta, Lambert attended his first integrated luncheons and dinners at the all black Morehouse College and joined the local chapter of the NAACP. He met with and brought a Jewish fraternal order into the local union movement. His brief interracial forays in Tennessee and Arkansas led Lambert toward deeper contact and even closer relationships across lines of race and ethnicity. Attending a single rally with African Americans was one thing, Lambert knew, but blacks and whites eating together and joining the same associations represented a powerful slap in the face to white supremacist culture of Dixie. Transgressing those barriers proved an important experiential lesson for the blossoming southern dissident.5

In the summer of 1937 the party asked Lambert to go to Dallas, Texas, a city whose growing working population they hoped to organize. By early August Lambert had joined Socialist organizer Herb Harris and Texas party chief Carl Brannin in projecting political films at various venues around town, hoping that the impromptu screenings would attract a few party members. The trio of activists took turns performing various tasks—advertising the venue, hitting the streets to recruit attendees, dealing with local authorities, setting up the projector, introducing the films, and finally asking participants to join the cause. They staged a screening outside City Hall and might have attracted a few converts, but other, more hostile audiences around Dallas also took notice.

A few days after the event downtown, the activists advertised another film screening at a park across the street from the South Texas Cotton Mill. This time it did not go as planned. The agenda included a double feature of Pare Lorentz’s The Plow that Broke the Plains, a history of the Dust Bowl sponsored by the New Deal, and Millions of Us, a Socialist propaganda piece. The first film proceeded without incident, but Lambert grew increasingly nervous as a number of “big husky fellows” who were “obviously not textile workers” began to gather around them. As Harris loaded the second film, “somebody shouted, ‘Get the goddam Communists. We don’t want any reds in Dallas!’ ” Between fifty and one hundred of the “husky” men stormed the organizers, scattering the crowd. “The next thing I knew, I had been knocked to the ground, and I could hear and see the sound truck being pitched over and the motion picture projector being shattered,” Lambert later recalled. The young West Virginian was beaten until he lost consciousness; Brannin fled and managed to escape. The attackers kidnapped Harris, beat him, coated him with a tarlike substance, and rolled him in feathers. Then they deposited him in an alley behind the Dallas Morning News. Photographers from the paper, whom the attackers had already tipped off, waited to take pictures, one of which ran on the front page the next day. City police were nowhere to be found.6

The assailants seemed to emerge out of thin air, but it soon came to light that officials of the Ford Motor Company plant in East Dallas had orchestrated the attack. By that time, Ford remained the lone nonunion holdout among the Big Three American automakers. The previous winter, the United Auto Workers (UAW) in Flint, Michigan, had used the sit-down strike pioneered in Atlanta to bring General Motors to its knees. Chrysler soon flinched as well, agreeing to recognize the union in order to avoid a similar strike. Ford alone continued to resist. It’s unlikely that the firm’s small Dallas plant figured prominently in its strategy to combat the influence of organized labor at its larger factories in and around Detroit. Still, local company officials—like their counterparts across the country—moved to combat the rising tide of unionization on their shop floor and the larger community. Drawing on the strength of the Dallas Open Shop Association (DOSA), an antiunion business alliance leftover from the 1920s antilabor offensive, local Ford leaders enlisted an army of “goon squads” to intimidate, harass, and, when all else failed, beat the tar out of any and all subversives in town. The latter group included both the “outside agitators” like Lambert and the local people who sympathized with them. The goons coordinated their attacks with the city’s antiunion newspaper as well as with the police, who agreed not to interfere with the plans of a leading manufacturer.7

Such was the atmosphere for organizing in Dallas—and indeed, in much of Texas—during the long, hot, and mostly forgotten summer of 1937. Lambert and his colleagues had stumbled right into the trap. The activists’ film screening had no connection to the Ford plant, and the organizers had no Communists in their ranks. Still, local Ford management, with help from corporate headquarters in Detroit, offered a handful of workers lucrative jobs in the “outside squad,” a company of goons who specialized in roaming around town beating down all labor and leftist efforts. Hundreds of other Ford workers were forced to join the “inside squads,” which normally were confined to spying on their colleagues within the plant. Those that declined to serve in this capacity were threatened with losing their jobs.8

But the real power lay not in the half of the working class that Ford hired to kill the other half, to paraphrase the words of nineteenth-century robber baron Jay Gould.9 Rather, merchants and industrialists across the city coordinated their actions through DOSA. The trade group shared “an interlocking directorate” with the Dallas Chamber of Commerce that in turn dominated local politics. The chamber made appeals to outside industry by claiming that it was free from the labor agitation that plagued the Northeast, Midwest, and West Coast. For its part, the association threatened to levy a $3,000 fine against any business that knowingly hired a card-carrying union worker. Ford led the charge, but it remained part of a broader, coordinated campaign to stymie industrial unionism and political radicalism.10

Still, despite this massive effort, Dallas remained riddled with labor organizing. Two years before the beatings at the park, in 1935, white, black, and Mexican American women joined the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and went on strike at all thirteen garment factories in the city. Representing approximately 40 percent of the industry’s workers in the state, the unionists voted overwhelmingly to walk off the job in protest of “sweatshop-like conditions” in the plants. When employers hired replacement workers during the industry’s all-important “Market Week,” the union maids confronted the scabs on the street and stripped off their clothes using pin hooks, the small blades attached to thumb rings that were a mainstay of the seamstresses’ craft. The spectacle “stripping party” represented a declaration of independence for Dallas’s long-invisible working women, a feat that earned not just local media coverage but also international publicity. Each of the unionists was fined twenty-five dollars and sentenced to three days in jail. A “don’t buy” campaign promoted by the Texas State Federation of Labor failed to bolster the union’s cause significantly, and the conflict fizzled out nine months after it began. Nonetheless, the garment manufacturers still made good on their pledge to the DOSA by blacklisting the strikers, leaving them unable to find new jobs in Dallas.11

Such repression, combined with the weakness of local American Federation of Labor (AFL) unions, gave Dallas the reputation of “the w...