- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

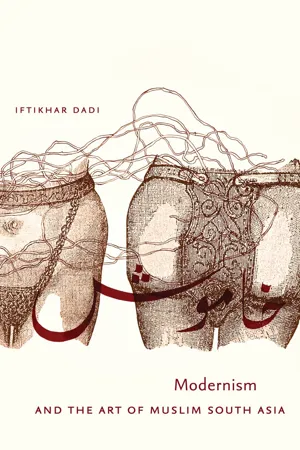

Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia

About this book

This pioneering work traces the emergence of the modern and contemporary art of Muslim South Asia in relation to transnational modernism and in light of the region’s intellectual, cultural, and political developments.

Art historian Iftikhar Dadi here explores the art and writings of major artists, men and women, ranging from the late colonial period to the era of independence and beyond. He looks at the stunningly diverse artistic production of key artists associated with Pakistan, including Abdur Rahman Chughtai, Zainul Abedin, Shakir Ali, Zubeida Agha, Sadequain, Rasheed Araeen, and Naiza Khan. Dadi shows how, beginning in the 1920s, these artists addressed the challenges of modernity by translating historical and contemporary intellectual conceptions into their work, reworking traditional approaches to the classical Islamic arts, and engaging the modernist approach towards subjective individuality in artistic expression. In the process, they dramatically reconfigured the visual arts of the region. By the 1930s, these artists had embarked on a sustained engagement with international modernism in a context of dizzying social and political change that included decolonization, the rise of mass media, and developments following the national independence of India and Pakistan in 1947.

Bringing new insights to such concepts as nationalism, modernism, cosmopolitanism, and tradition, Dadi underscores the powerful impact of transnationalism during this period and highlights the artists' growing embrace of modernist and contemporary artistic practice in order to address the challenges of the present era.

Art historian Iftikhar Dadi here explores the art and writings of major artists, men and women, ranging from the late colonial period to the era of independence and beyond. He looks at the stunningly diverse artistic production of key artists associated with Pakistan, including Abdur Rahman Chughtai, Zainul Abedin, Shakir Ali, Zubeida Agha, Sadequain, Rasheed Araeen, and Naiza Khan. Dadi shows how, beginning in the 1920s, these artists addressed the challenges of modernity by translating historical and contemporary intellectual conceptions into their work, reworking traditional approaches to the classical Islamic arts, and engaging the modernist approach towards subjective individuality in artistic expression. In the process, they dramatically reconfigured the visual arts of the region. By the 1930s, these artists had embarked on a sustained engagement with international modernism in a context of dizzying social and political change that included decolonization, the rise of mass media, and developments following the national independence of India and Pakistan in 1947.

Bringing new insights to such concepts as nationalism, modernism, cosmopolitanism, and tradition, Dadi underscores the powerful impact of transnationalism during this period and highlights the artists' growing embrace of modernist and contemporary artistic practice in order to address the challenges of the present era.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia by Iftikhar Dadi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Asian Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 ABDUR RAHMAN CHUGHTAI

MUGHAL AESTHETIC IN THE AGE OF PRINT

Abdur Rahman Chughtai (1897–1975) is generally considered the first significant modern Muslim artist from South Asia. But this statement itself is not as simple as it appears at first glance. Specifically, none of its claims—of his precedence, his modernity, and his status as an artist—were settled matters when he began his career. Rather, during Chughtai’s long career, which spanned over fifty years of highly concentrated and intense activity, his supporters and critics repeatedly resurrected these questions for debate. Beginning in the 1920s, perspectives on the modernity of Chughtai, and on his status as an artist, have been offered in Urdu and in English; yet art historical debate in Urdu and English on Chughtai has largely attached itself to literary criticism and the orientalist understanding of Islamic art, not least by Chughtai himself. This chapter focuses on the critical reception of Chughtai by Urdu literary critics and authors from the 1920s and through essays on the artist in English. This complex interaction between Urdu literary concerns and the emerging understanding of Persian miniature, Mughal painting, and other painting traditions in India shaped the horizon of Chughtai’s career. Apart from his voluminous painterly output, Chughtai served as a partisan and provocateur in locating himself in the rediscovery of a complex inherited painterly tradition. The artist articulated his views in a series of important essays on aesthetics in Urdu, texts that have as yet not been critically examined at length. His work must also be situated in relation to his brother Abdullah Chughtai’s scholarly researches into Mughal and Persian painting, calligraphy, architecture, and ornament, as forming a broader revival of Mughal aesthetics during the early and mid-twentieth century.

This chapter demonstrates how Mughal nostalgia serves to decenter Chughtai’s identification with a specific national site, projecting it instead onto earlier Islamicate and Persianate cosmopolitanism.1 Chughtai remained ambivalent about the ceaseless transformation enacted by modernity yet incorporated his subjectivity into his reworking of the miniature. Accordingly, his later works are undated, unsigned, and evocative of the lost Mughal past. Chughtai’s self-orientalism was a response to late colonialism: his modernity lies in his insistent foregrounding of his “Muslim” subjectivity by development of a distinct style, and his friendships within the literary and intellectual circles in Lahore sought to create a discursive framework in which his paintings and his self might be fashioned. Moreover, his participation in exhibitions organized by art societies and the dissemination of his style via print culture created new audiences. This chapter briefly sketches the nineteenth-century background of painting in the Punjab and aesthetic debates in Bengal, examining the influences of the Bengal School of Painting on Chughtai. It then discusses Chughtai’s career and the reception of Chughtai’s later works in the context of the emergent literary culture in Lahore.

PAINTING IN THE PUNJAB

Painting in the Punjab since the mid-nineteenth century consisted of a variety of intersecting residual, dominant, and emergent forms and practices.2 Punjab had been under Mughal rule earlier and was subsequently under Sikh rule before the British began exerting direct control over much of it in the middle of the nineteenth century. Various artisanal practitioners of miniature Mughal and Sikh painting continued their work through the nineteenth century, but under increasingly difficult circumstances. Two important types of practitioners were known as naqqash and musavvir. The former worked on illumination and ornamentation of legal and ritual documents and borders of Arabic and Persian manuscripts and would at times also work as skilled calligraphers. The scholar Abdullah Chughtai, younger brother of Abdur Rahman, notes that the color schemes of the naqqash differed from those of the musavvir, who created miniature paintings of “animated objects.”3 During this period, non-Muslims patronized representational arts more frequently than Muslims. These commissions included wall murals that depicted religious, mythological, and everyday themes of leisure. Architectural decoration also included nonrepresentational arabesque schemes on building facades. The term mimar, used by Abdullah Chughtai in regard to many of his ancestors, refers to a builder/architect, while the word muhandis implied a builder endowed with engineering skills.4 In the wake of the lithographic print revolution sweeping India during the nineteenth century, book illustrations based on miniature and popular painting began to accompany vernacular publications. These included themes from Hindu mythology as well as poetry and folktales from the Punjab. To dramatize their stories, bazaar performers (including women) would display albums of narratives of myths and scenes of punishments from hell. At the turn of the century, painters sold their popular works on the sidewalks and at festivals to the public at very affordable rates.5 Another important type of miniature painting was patronized by local rulers of states in the Punjab Hills. Due to a comparative lack of patronage by Muslims for representational art, many Muslim painters routinely painted Hindu mythological themes, sometimes rendered in a miniature style and format, while others created illusionist mythological works based on European academic styles.6

The case of Ustad Allah Bukhsh (1895–1978), who was of the same generation as Chughtai, exemplifies some of the dilemmas of securing patronage and of the formalist possibilities available to a painter who was not yet influenced by the Bengal School revolution (which is discussed shortly).7 Allah Bukhsh began his career as a sign painter in Lahore, painting letters and numbers on railway carriages. He moved to Calcutta in 1914, painting stage sets for dramatist Agha Hashar Kashmiri, and then went back and forth between Bombay and Lahore from 1915 to 1919, working as a portrait painter. From 1919 to 1922, he was an illustrator for a vernacular newspaper in Lahore. During his second stint in Bombay, from 1922 on, he began a commercially lucrative career painting multiple copies of Lord Krishna and other Hindu iconography, to the extent that he became recognized in India as the “Krishna artist.”8 His output included landscapes and portraits executed in oil, using British academic styles and informed by prevalent academic paintings and prints of Hindu mythology, Punjabi folktales, and romantic landscapes with detailed renderings of rocks and other natural forms.9 Allah Bukhsh’s lack of formal education and social capital, his reliance throughout his life on academic oil painting, and his lack of a sufficiently individual signature style meant that his artistic persona remained confined within an older, artisanal mode of visual practice rather than emerging as a full-blown modern artistic subject ushered in by the Bengal School. The artist Zubeida Agha recounted an anecdote regarding a visit to Dacca in 1954 with him: “Allah Bukhsh expressed surprise at being honoured as an artist. He told her that he was ‘of the rank of tarkhan [carpenter] and loharan [blacksmith] and did not know how he became an artist.’”10 Allah Bukhsh’s paintings are usually unsigned and undated, and although Chughtai also followed this practice, the difference in their artistic subjectivity is crucial in terms of their social location in modernity.11 Another figure contemporary to Chughtai was Haji Sharif (1899–1978), who rendered versions of Mughal and Pahari miniature paintings, taught traditional miniature painting at the Mayo School of Art in Lahore from 1945 to 1966, and also worked in an artisanal, craft-based mode.12 Again, Chughtai’s practice departs from Sharif’s in charting a new path by situating himself as a modern artist. Chughtai firmly established individual artistic subjectivity and imagination as a central motif in his work. He also recognized that modern patronage and audience arrangements had decisively shifted since the Mughal era and thus depended upon the circulation of print culture to disseminate his work.

As an artist, Chughtai rises above the artisanal and commercial arena in which Haji Sharif and Allah Bukhsh remained for much of their lives. Chughtai’s formation was shaped by the mediation of ideas of subjectivity and imagination that emerged in the wake of the Bengal School rather than by the commercial possibilities available to illusionist painters such as Allah Bukhsh or to the small number of miniature “copyists” such as Haji Sharif. Despite his reliance on the Mughal tradition, Chughtai’s modernity lies in his insistent foregrounding of his own subjectivity; the development of a style associated with, yet distinct from, the Bengal School; and his friendship with the literary and intellectual circles in Lahore that sought to create a discursive framework in which his paintings might be understood. But Chughtai’s modernity is also paradoxical as the static formal and thematic universe evoked by his art offered a counterpoint to his social location in a turbulent, decolonizing historical process.

Emerging since the mid-nineteenth century were art schools founded in India under British patronage, which provided technical training based on Arts and Crafts principles.13 The Mayo School of Art, based in Lahore, was founded in 1874 under the principalship of John Lockwood Kipling (father of novelist Rudyard Kipling), and the training at Mayo heavily emphasized the renewal of traditional craft skills rather than fine art.14

BENGAL SCHOOL OF PAINTING

During the late nineteenth century, ma...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- MODERNISM AND THE ART OF MUSLIM SOUTH ASIA

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION MODERNISM IN SOUTH ASIAN MUSLIM ART

- CHAPTER 1 ABDUR RAHMAN CHUGHTAI

- CHAPTER 2 MID-CENTURY MODERNISM

- CHAPTER 3 SADEQUAIN AND CALLIGRAPHIC MODERNISM

- CHAPTER 4 EMERGENCE OF THE PUBLIC SELF

- EPILOGUE THE REALM OF THE CONTEMPORARY

- GLOSSARY

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX